Jewish Women and Comedy

Comedy has been a systemically misogynistic field, both because of the ways men monopolized creative control and because the content of many comedians’ acts are deeply disparaging of women. This article includes examples demonstrating why comedy has been such a difficult field for women. It then focuses on the careers and contributions of remarkable Jewish women of different eras and in different media, including Sophie Tucker Fannie Brice, Gertrude Berg, Anne Beatts, and Janis Hirsch, all of whom defied the odds and forced their way into a hostile industry. It ends with a look to the future and the way women like Miriam Anzovin give hope for the future of Jewish women in comedy.

Problems in The Industry

While most industries have traditionally been dominated by men, comedy has been actively hostile towards women, particularly in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This hostility is visible in both the hurdles women have needed to overcome in order to be working comedy professionals and the long history of the ways women, and Jewish women in particular, have been portrayed in comedy. In this article I will establish some of the factors that have made comedy a particularly misogynistic art form and how this misogyny has manifested in Jewish humor, as a backdrop to chronicling some of the remarkable contributions of Jewish women to the world of comedy. While an article about women should not focus on the bad behavior of men, understanding the systemic and structural barriers to women’s success in comedy is necessary to truly appreciate what these women have accomplished.

One need look no further than the number of men called out by both the #TimesUp and #MeToo movements to see that the behavior of many men and the treatment of women in comedy spaces have far to go before most writers’ rooms or comedy clubs will be able to be considered comfortable places for women to work. The struggles women face in comedy come as no surprise, given the way modern (1920s vaudeville-era and beyond) comedy by men has used women. Take, for example, Eddie Cantor, a Jewish comedian known for his big-eyed facial expressions and his racist blackface performances. He was a comedy song and dance man, both in and out of blackface. In his staple song “The Dumber They Come, The Better I Like ‘Em” (1924), Cantor explained why smart women were both unattractive and too much bother, while “dumb” women were sexually appealing. The song includes lyrics such as “Those educated babies are a bore/I'm gonna say what I said many times before/Oh, the dumber they come, the better I like 'em/'Cause the dumb ones know how to make love” and “The smart girl's speaking Greek and other languages too/But the dumb girl's only language is a coochie coochie coo.”

In the final stanza of “The Dumber They Come,” Cantor mentions “dumb Dora,” a stock vaudeville character that persisted well into the television era. Dumb Dora was the female half of a man/woman comedy duo who generally existed to be a font of malapropisms and inane opinions that her partner—and the largely male audience—could laugh at and feel superior to. Gracie Allen, in her role opposite her partner and eventual husband George Burns, is the best-known Dumb Dora, although in her case the mistakes often ended up working out and the act was not as mean-spirited as many Dumb Dora routines. Unlike the comic strip Dumb Dora (1924-1936), for example, which was prone to mocking Dora’s lack of education, the television audience was meant to like Gracie, despite her malapropisms and misunderstandings.

Then, of course, there was Henny Youngman, who in the 1950s gave us the “take my wife, please” form of comedy. Youngman and other comedians of his generation began focusing their acts on how terrible their wives, and later their daughters, were. These performances, honed in the Jewish enclave of the Catskills and later brought to wide audiences on shows like The Tonight Show, introduced the monstrous figures of the Jewish mother and the Jewish American Princess. These women were ugly, nagging, manipulative, overbearing guilt machines or pretty, vapid, spoiled, frigid, materialistic narcissists. It is not surprising that men like John Belushi famously believed that women were unable to do comedy. What is surprising is that any women managed to rise above these impediments and find success in comedy, but many did, and the contemporary comedy scene offers greater opportunities for women with each passing year.

Vaudeville to Radio: 1920s-1940s

The art of comedy underwent several major evolutionary changes in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, most of which aligned with the introduction and popularity of new media. Jewish women were important both in developing the new forms of comedy and in bringing comedy to ever-wider wider audiences.

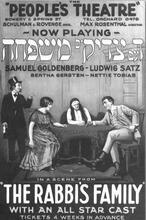

Vaudeville was, arguably, the first major American comedy medium and the antecedent to modern stand-up comedy. American vaudeville in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries consisted of variety shows made up of series of acts, from singers to acrobats to trained animals to magicians to comedians. Many performers, including Eddie Cantor and the Marx Brothers, began their careers in vaudeville, but it was a difficult medium for women, especially for Jewish women. Vaudeville was slightly more family-friendly than burlesque, which was known for having striptease acts, but women in vaudeville were still encouraged to perform in attractive, alluring, highly sexualized manners.

Women—including many Jewish women—who did not or could not conform to white American standards of beauty were either shunted aside in vaudeville or made to perform in demeaning acts. Because women who had what were considered phenotypically Jewish appearances were thought to be undesirable, there were limited opportunities for them in American comedy performances. For example, Sophie Tucker’s biographers often mention that she was forced to perform in blackface because she was considered unattractive. Tucker hated blackface performance and ultimately became a star without it, but her struggle was typical of many female Jewish performers.

Fanny Brice and the Follies Girls beauty pageant, 1934.

Fanny Brice’s career is thus extraordinary in part because she refused to perform in blackface, even though she was also thought not to be conventionally attractive enough to be a star. In 1910, Brice was cast in Ziegfeld’s Follies, a vaudeville-style showcase on Broadway considered the high-profile (and high-budget) pinnacle of vaudeville. Brice went on to become one of the headline stars of the Follies in the 1920s, and although her 1923 rhinoplasty made the front page of the New York Times, she continued to incorporate Yiddish accents and Jewish characters into her comedy. Brice was able to balance giving audiences the types of performances they wanted without sacrificing her personal boundaries. So while she would not perform in blackface, she would, for example, do “dialect humor,” affecting a Yiddish accent despite not speaking any Yiddish herself. She would perform broad physical humor that poked fun at her own lack of conventional beauty, but she made herself, not other women, the butt of those jokes. Unfortunately, not many of Brice’s early performances exist on film, but one surviving clip from 1934 illustrates this element of her comedy. She appears along with the Follies Girls of 1934 in a beauty pageant where she is meant to be a judge but believes she should be a contestant. The sketch makes fun of her nose, her profile, her figure, and even the shapely fake leg she eventually pretends is her own, but she mocks only herself, not the other, more conventionally attractive women. Brice spent the later years of her radio and television career performing a character she developed called Baby Snooks, which some saw as a step down from the heights of her comedic success, but her legacy was cemented when the musical about her career, Funny Girl, was nominated for the 1964 Tony Award for Best Musical. (It lost, coincidentally to another musical about a Jewish woman, Hello, Dolly!) Barbra Streisand originated the role of Fanny Brice in the Broadway production of Funny Girl and went on to win her first Academy Award for playing the role in the film adaptation. Brice set the bar for being a successful woman in comedy quite high indeed.

Radio to Television: 1940s-1980s

Gertrude Berg saw that bar and surpassed it. She developed a radio program, The Rise of the Goldbergs, that followed a Jewish family in the Bronx through its trials and tribulations. It was one of the most popular and longest-running scripted radio shows, and Berg became one of the first women to write, produce, and star in her own series. Although few radio shows successfully made the transition to television, Berg was able to convert The Rise of the Goldbergs into The Goldbergs, which had several successful seasons on television. There was a comfortable nostalgia about the show, which depicted a Jewish world that had not truly existed in decades by the time the show aired. That sense of nostalgia was, unfortunately, lost when the network pushed Berg to modernize the show and move the family to the suburbs, as so many American Jews had done by the early 1950s. The audience responded poorly to the change and the show was canceled, but Berg’s influence on the industry was undeniable and every single-set family sitcom can trace its lineage to The Goldbergs.

As television became more ubiquitous and comedy on television grew into a major industry, however, it became harder and harder for women to achieve the kind of creative power and control Berg, and to a lesser extent Brice, had had. The writers’ room of Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows was the most famous comedy incubator, in part because so many comedians emerged from it and immortalized it in various ways. The room typically had “a girl,” a role filled at points by Selma Diamond and Lucille Kallen, both of whom reported that they were not taken seriously by their male counterparts and were only consulted when someone thought a sketch needed a “female perspective.” They were seen as so interchangeable that Neil Simon conflated the two into a single character for Laughter on the 23rd Floor, as did Carl Reiner for The Dick Van Dyke Show, two fictionalized recreations of Caesar’s writers’ room.

The cliché of the writers’ room “girl” was re-enacted on Reboot (premiered 2022), which portrays a conflict between the racial and gender diversity reflected by the writers hired by young showrunner Hannah (played by Rachel Bloom) and the several Jewish men and one woman (even named Selma) brought in by the older Gordon. Selma is depicted as fitting in with the men by being the most foul-mouthed of the bunch. This scenario reflects the experience of most women trying to work in comedy in the second half of the twentieth century: there might be one, but only ever one, “girl” on staff, and she was rarely seen as equal to her male coworkers.

The career of someone like Janis Hirsch is thus particularly notable. Hirsch began writing comedy shortly after graduating from college and was hired as a writer for the National Lampoon production Lemmings, a theatrical revue that ran off-Broadway in 1973. On Lemmings, Hirsch met fellow writer and fellow Jew Anne Beatts, who in 1982 hired Hirsch as part of her proposed all-female writing staff for her television series Square Pegs. (Despite the fact that Beatts felt a show about teenage girls should be written by women, the network eventually forced her to hire a man.) From there, Hirsch went on to write two highly acclaimed first season (1986-1987) episodes of It’s Gary Shandling’s Show. As was so often the case, she was usually the only woman in the room. Hirsch left the show very suddenly during the first season and went on to write and produce numerous other high-profile comedy shows. Not until the #MeToo movement of the late 2010s did she reveal that she had not left Shandling’s show by choice. Rather, she had been forced to resign the day after she was sexually assaulted in a meeting; a male co-writer stood behind her and draped his penis over her shoulder.

Television allowed women to perform in a much broader range of genres than those to which they had been limited in vaudeville, but it also further entrenched some of the expectations for Jewish women in comedy. A look at three very different Jewish comedians offers an example of larger trends. Joan Rivers, Roseanne Barr, and Gilda Radner all found great success on television, but they also all both fought against and sometimes conformed to the stereotypes they inherited.

Promotional head shot of Joan Rivers by her talent agency, Rollins and Joffe, Inc., in 1967.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Arguably no woman did more to break comedy’s glass ceiling than Joan Rivers. In 1963 Rivers was a guest on The Tonight Show, at the time the “big break” most stand-ups hoped for. She rapidly gained fame after her appearance, and Johnny Carson brought her back several more times. Rivers went on to guest host the show 93 times, more than any other guest host except Joey Bishop; when she launched The Late Show with Joan Rivers in 1989, she was the first woman to have her own late-night talk show. Much like the Selma character on Reboot, however, Rivers succeeded in a man’s industry in part by being even more cutting than the men were. Her early jokes were largely at her own expense, mocking her looks, her marriageability, her lack of career prospects, or her personality. After her talk show ended in 1993, she found new fame as a red carpet correspondent; for years she was a fixture at award shows, mercilessly making jokes at the expense of the women she interviewed and saw walking the carpet.

Roseanne Barr from Jordan Brady's film "I Am Comic."

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Similar things can be said about the career of Roseanne Barr. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, TV sitcoms centered around a stand-up comedian became the new “big break” all comedians sought, and almost all of these headlined shows were built around male stand-ups (Seinfeld, Mad About You, Home Improvement, etc.). Premiering in 1988, Roseanne Barr’s Roseanne was one of the few shows built around a woman. Barr’s standup, like Rivers’, was largely self-deprecating (she frequently called herself ironically a “domestic goddess” as she told stories about her lackluster housekeeping and indifferent child rearing), and her TV show was built around the idea of her as a lower-middle class, blue-collar, foul-mouthed housewife. She made frequent use of fat jokes aimed not only at herself but at her on-screen husband played by John Goodman, and while her fictional family the Connors was explicitly not Jewish, the show nevertheless derived much of its comedy by playing up the perceived unattractiveness of its Jewish woman star.

Gilda Radner’s career both bucks and conforms to this same trend. Radner rose to prominence as part of the first season cast of Saturday Night Live (1975). While many of her characters were performed as unattractive (Roseanne Roseannadanna, for example) or painfully nerdy (Lisa Loopner), she also often performed characters who were meant to be beautiful and alluring. Marilyn Suzanne Miller, one of the writers for SNL in those early seasons, she often speaks about the way she and Radner wanted to depict Jewish women differently. In the 1970s and 80s, when “the stereotype around Jewish women was to be the sidekick’s sidekick,” Miller reflects, “‘Gilda (Radner) and I were intent on that not being the case,’” (NFTY Alumni Profile). Radner’s career shows that it was possible for Jewish women to be seen as beautiful and desirable, but Radner and writers like Miller recognized that to depict a Jewish woman as both funny and beautiful was revolutionary.

Television to the Internet and Beyond: 21st Century

Comedian and actress Amy Schumer in 2011.

Photo courtesy of Mario Santor via Wikimedia Commons.

While the twenty-first century has not brought a miraculous breakdown of the barriers facing women in comedy, progress is happening. More and more women are taking a page from Gertrude Berg and Anne Beatts by creating their own shows and refusing to cede creative control. Rachel Bloom of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer of Broad City have produced unapologetically feminist, Jewish comedies as part of the new “Golden Age of Television.” Joey Soloway based Transparent on their own complicated family, showing that the progress made by pioneering women in comedy is also helping writers of other minoritized genders. The growth of streaming platforms and subscription-based content has opened the door for a host of new opportunities for Jewish women in comedy. Reality shows have also offered opportunities for women to bypass the long, hostile climb through comedy clubs. For example, Amy Schumer’s career was made when she competed on (although did not win) the series Last Comic Standing.

Women are also capitalizing on the explosion of internet-based platforms, which allow anyone to produce and publish their own forms of comedy with little to no overhead costs or external control, opening comedy up to people who might previously have had a difficult time finding an audience. From Rachel Bloom gaining notoriety for her satiric YouTube videos to the #CrazyJewishMom Instagram feed bringing fame to both Kate Siegel and her mother Kim, the internet has opened doors for independent content creators to share their comedy.

Miriam Anzovin had been writing satiric work and hosting a podcast for JewishBoston.com when she decided to try her hand at TikTok “reaction videos,” short-form videos of people reacting to various things. Anzovin had been working through the seven-and-a-half year Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study, and since her commentary made her study partner laugh, she thought others might enjoy it as well. She put her first video up in late 2021, expecting “maybe five people” to watch it; by January 2022 she had gone viral, and tens of thousands of viewers watched her discuss the daily Talmud page. Anzovin has expressed an appreciation for the way the internet has allowed groups of people who may not always feel welcome in traditional Jewish spaces to engage with Daf Yomi, especially as the cycle to which she has been reacting started in January 2020, just weeks before the pandemic made in-person study impossible. The internet has similarly made a space for marginalized groups to engage in Judaism, comedy, or sometimes both in new and exciting ways.

There is still a long, long way to go before comedy takes women as seriously as men and provides as many opportunities to women as it does to men. The dramatic shift in representation in the twenty-first century, however, indicates that real progress is being made. As more and more free internet platforms develop, more people who would previously have faced systemic and social difficulty achieving success in comedy will find their audience. Comedy continues to be seen as a “boy’s club,” and women who dare to violate that sanctity are subject to all sorts of injustices, from having their jokes and sketches be claimed by men to outright harassment and assault. However, a new generation of Jewish women in “making trouble” in ways their comedic foremothers, one assumes, would find exciting, heartening, and inspiring.

Anzovin, Miriam (@mimiriamanzovin). 2022. TikTok.

Beatts, Anne. Square Pegs. Culver City: Sony Pictures, 1982

Berg, Gertrude. The Goldbergs. Eugene, OR: Timeless Media Group, 2008.

Berg, Gertrude. Molly and Me. New York: McGraw Hill, 1961.

Berg, Gertrude. The Rise of the Goldbergs. New York: NBC, 1929

Bloom, Rachel. Crazy Ex-Girlfriend. New York: The CW, 2015.

Caesar, Sid. Caesar’s Hour. New York: NBC, 1954

Caesar, Sid. Your Show of Shows. New York: NBC, 1950

Caplan, Jennifer. “Modern Judaism and the Golden Age of Television.” Companion to American Religious History, edited by Benjamin Park, 371-382. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

De Costa, Harry. “The Dumber They Come, The Better I Like ‘Em.” New York: Waterson, Berlin, & Snyder Co., 1924.

Jacobson, Abbi and Ilana Glazer. Broad City. New York: Comedy Central, 2014.

Monod, David. Vaudeville and the Making of Modern Entertainment. Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

National Lampoon. Lemmings. New York: Decca Broadway, 1973.

NBC Universal, Last Comic Standing. 2003.

“NFTY Alumni Profile: Marilyn Suzanne Miller.” Union for Reform Judaism, July 14, 2014; https://urj.org/blog/nfty-alumni-profile-marilyn-suzanne-miller.

Palumbo, Dennis. My Favorite Year. Beverly Hills: MGM Studios, 1982

Reiner, Carl. The Dick Van Dyke Show. New York: CBS, 1961

Sklaroff, Lauren Rebecca. Red Hot Mama: The Life of Sophie Tucker. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018.

Shandling, Gary. It’s Gary Shandling’s Show. New York: Showtime, 1986

Simon, Neil. Laughter on the 23rd Floor. New York: Random House, 1995.

Soloway, Joey. Transparent. Culver City: Amazon Studios, 2014.

Styne, Jule and Bob Merrill. Funny Girl. New York: Hal Leonard, 1964.

Wyler, William. Funny Girl. Culver City: Columbia Pictures, 1968.