Women, Music, and Judaism in America

First Women Cantors’ Network Conference, Congregation Beth El

Norwalk, CT, May 1982. Left to Right: First row: Deborah Katchko (Norwalk, CT), Linda Shivers (Highland Park, NJ), Doris Cohen (Flushing, NY), Rochelle Helzner (Washington, D.C.), Jane Myers (Philadelphia, PA), Elaine Shapiro (W.Palm Beach, FL), Ruth Devorah (New York, NY). Second row: Sue Roemer (Silver Spring, MD.), Tzippy Bronstein, (Brooklyn, NY), Sheyne Mueller (New York, NY). Third row: Rita Glassman (New York, NY). Courtesy of the Women Cantors’ Network.

American Jewish women’s music has for more than a century been discussed in limiting terms; restrictive categories of musical genre, narratives of women’s “emergence” into male-coded spaces, and inherited wisdom about “Jewish music” have together concealed the diversity and cultural influence American Jewish women’s music. Rather than classifying the music American Jewish women created into these often limiting (and often male-coded) categories, this article discusses Jewish-identifying women’s broader musical activities in both religious and non-religious settings. The article highlights women’s contributions to amateur music-making in the home, music scholarship, liturgical music, Yiddish music, professionally recorded music, and more to illustrate the diverse modes of American Jewish women’s musical choices.

Introduction

Fully understanding the prolific history of women, Judaism, and music in America requires cutting through more than a century of inherited wisdom about the content and practice of “Jewish music.” Women have been deeply involved in Jewish communal, civic, and concert musical life from the earliest days. However, nineteenth-century efforts by (mainly male) scholars and cantors coded “Jewish music” as a male-dominated activity, with the synagogue and cantor at its center. Reinforced by rabbinical concerns over women’s voices, colloquially known as “Kol Isha,” this self-interested scholarship generally marginalized the musical activities of women as exceptions, auxiliaries to tradition, or liberal breakthroughs. (To cite one example: advocates of Jewish reform, while noted for their inclusion of women, also established the cantor as a normatively male figure in mixed-gender congregations.) More recent generations of researchers are rethinking these assumptions.

This article emphasizes American Jewish women’s multivalent musical choices rather than narratives of “emergence” into male-coded American Jewish music spaces. In doing so, it acknowledges that mainstream Jewish liturgical, educational, art, and “popular” music histories often exclude or minimize women’s participation—emphasizing “famous” cantors, composers, and performers, for example, while largely ignoring the many women who served as choir directors, organists, choristers, and local musicians in small- and medium-sized communities. It also acknowledges that the term “Jewish music” itself has long skewed male. Consequently, this article focuses on Jewish-identifying women’s activities in both religious and non-religious settings, rather than seeking to classify the music they create.

Jewish Women and Musical Leadership

Courtesy of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, OH, www.americanjewisharchives.org and the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods.

Photo from A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life, Frances E. Willard and Mary A. Livermore, eds. (Buffalo: Charles Wells Mouton,1893), 1812.

The communal musical practices of Jews in the early American republic often derived from contemporary practices in Europe and the Caribbean. In Europe, Fanny Arnstein, the Mendelssohns, and various members of the Rothschild family (among others) fostered music and the arts through salons that welcomed and supported prominent musicians (both Jewish and non-Jewish), with women often serving as hosts, performers, pupils, and patrons. In America, women in Jewish mercantile families similarly created prominent musical spaces for community and family life in port cities such as New Orleans, Louisiana; Norfolk, Virginia; and Charleston, South Carolina. In Charleston, for example, Penina Moïse hosted visiting musicians and literati and promoted conversation circles in her family home; she also produced and distributed collections of her own poems and hymns.

Middle-class Jewish women supported a prolific culture of amateur music making in homes, schools, houses of worship, and public venues, serving as educators, patrons, and de facto worship leaders. Among her many activities, for example, Philadelphia’s Rebecca Gratz taught children liturgical and hymn tunes during her Sunday religious school lessons. Music’s value as a gateway to literate society, moreover, meant that women’s contributions to Jewish communal activity often had connections to local musical events. In Jewish community-connected literary clubs, where young women and men gathered on weekend afternoons, musical performances complemented recitations, debates, and playlets in salon-like settings. Women also organized civic events, balls, activities for amateur singing societies, and benefit concerts for both Jewish and non-Jewish organizations, which often included local women as performers and participants, sometimes alongside travelling musicians.

These activities crossed fluidly into the synagogue. By the 1850s, American reformers such as Isaac Mayer Wise championed women’s voices as pillars of progressive Jewish worship and an inflection point against orthodoxy—even though women also sang openly in some self-described Orthodox synagogues at the time. As amateur choirs proliferated in progressive (and to a lesser extent, Orthodox) congregations, women often claimed responsibility for organizing and sustaining them. At Hannah Marks’ 1857 Cincinnati wedding, for example, officiating Rabbi Max Lilienthal “spoke of her attachment of establishing a choir in the Synagogue, and stated that, but for her devotion to it, it would no doubt have failed” (“Nuptials at the Jewish Synagogue,” 1857). In Owensboro, Kentucky, the teenaged Esther Goldammer served as the organist and musical director of the town’s synagogue choir between 1877 and 1879, while her father served as rabbi. And in Charleston, South Carolina, Laura Wineman served as choir director and alto soloist of congregation KK Beth Elohim for nearly two decades in the years after the Civil War. While well-financed urban congregations had the resources to hire professional singers, smaller congregations with volunteer choirs relied more often on women from the community as both participants and leaders. A surviving book of three-part choral hymn arrangements at Charleston’s KK Beth Elohim—featuring two women’s parts and one men’s part—reflects the reality of Jewish congregational music across a good portion of the country.

By the latter decades of the nineteenth century, as liberal and Orthodox Jewish groups increasingly defined themselves against each other, women were making significant contributions to American Jewish liturgy. Several of Penina Moïse’s poetic adaptations of German Jewish Reform hymns, and her original devotional poetry, became core texts for American synagogue hymnals. Emma Lazarus wrote devotional poetry for the Gottheil-Davis hymnal (1875/1887) adopted by Temple Emanu-El in New York City. Members of the Jewish Women’s Congress, organized in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, presented a major American Jewish liturgical publication, A Collection of the Principal Melodies of the Synagogue from the Earliest Time to the Present, compiled and edited by Alois Kaiser and William Sparger, as its souvenir. In San Francisco, “cantor soprano” Julie Rosewald led Temple Emanu-El’s liturgical singing from the choir loft for about a decade in the 1880s and 1890s, and other well-funded liberal congregations occasionally turned to their women soloists as de facto musical authorities. In Orthodox synagogues’ gender-separated settings, meanwhile, figures such as the sagerin (sometimes translated as “readeress”) would lead women in prayer; the few contemporary reports we have (all written by men) dismiss their sonic production as unmusical or derivative of male-dominated practice, suggesting a different aesthetic rather than a lack of skill.

From the 1910s through the 1940s, more than a dozen “woman cantors,” including but not limited to Sophie Kurtzer (1896-1974), Goldie Steiner (a woman cantor of color), Jean Gornish (Sheindele di Chasente, 1916-1981), Sadie Richman, Goldie Malavsky (1923-1995), and Bas Sheva (Bernice Kanfesky, 1925-1960), led liturgical music in both services and well-publicized sacred music concerts, sometimes with their own choirs, sometimes as part of all-women musical programs, and sometimes co-presenting with male cantors and/or family members. Surviving recordings suggest that these women often (but not always) sang with a vocal range and style similar to their male counterparts.

Fostering American Jewish Music Scholarship

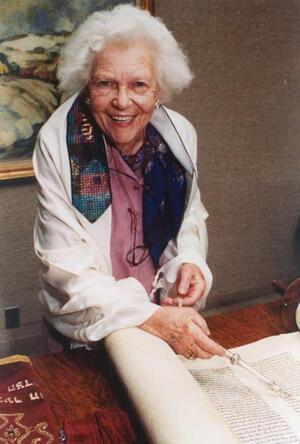

"No thunder sounded. No lightening struck," recalled Judith Kaplan Eisenstein of her history-making 1922 Bat Mitzvah ceremony, the first in America. She is pictured here at her second Bat Mitzvah ceremony, where she was honored by a number of prominent Jewish women, including Betty Friedan and Letty Cottin Pogrebin.

Institution: The Ira and Judith Kaplan Eisenstein Reconstructionist Archives, Reconstructionist Rabbinical College

Women also proved crucial in supporting and promoting the emerging field of Jewish music research. Angie Irma Cohon (1890-1981), for example, helped Latvian-born musicologist Abraham Z. Idelsohn translate his ideas about Jewish music for general audiences during his first years in the United States, organizing an American lecture tour for him in the early 1920s and coaching him on both the content and delivery of his talks. In 1923, the National Council of Jewish Women published Cohon’s adult education curriculum An Introduction to Jewish Music in Eight Illustrated Lectures, which standardized the topic. Cohon’s work, perhaps more than Idelsohn’s, gave congregational groups a template for Jewish music study over the following decades.

Miriam Shomer Zunser, co-founder and long-time president of MAILAMM (the America-Palestine Music Association) played a similar role with musicology in the 1930s, coordinating talks by a series of (male) émigré scholars and working to raise funds for a music department at the Hebrew University. Professional contralto Ruth Kisch-Arendt served as secretary for a successor organization, the Jewish Music Forum.

Women also held musical roles in Jewish institutions of learning, including the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, Hebrew Union College, and Yeshiva University/Stern College for Women. Kisch-Arendt, for example, headed the Stern College Department of Music in the 1960s. From its opening in 1948, the Hebrew Union College School of Sacred Music admitted women to Jewish liturgical music studies and offered them accreditation to serve congregations as music educators and choral leaders. Major scholars of Jewish music Johanna Spector (1915-2008), Judith Kaplan Eisenstein (1909-1996), and Edith Gerson-Kiwi (1908-1992) wrote doctoral dissertations on Jewish sacred music with the school’s co-founder Eric Werner; Jewish music scholar Irene Heskes (1923-1999) studied with Werner as well. Each went on to a public career that combined teaching, scholarship, and communal service. Spector joined the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in the 1950s, where she was soon joined by composers Miriam Gideon (1906-1996) and Tziporah Jochsburger (1920-2017) as instructors in the Cantors Institute; Spector also founded the JTSA’s department of ethnomusicology in 1962. Heskes compiled numerous foundational primary resource collections while working at the Theodore Herzl Institute and the Jewish Music Council; Eisenstein, who had taught music at the JTSA Teachers’ Institute since 1929, continued her career as a prominent Jewish educator and musical advocate, inspiring a number of women to follow in her footsteps. Judith Tischler, who also taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary, rose to the Directorship of Transcontinental Musical Publications, the premier publisher of liberal Jewish synagogue music, from 1981 to 2000. The persistent view of the cantor as normatively male, however, excluded women from recognition as professional clergy—especially following World War II, when major American Jewish seminaries sponsored cantorial training institutions partly to maintain male-coded European cantorial practices that had become symbols of Jewish religious continuity. Despite the presence of women faculty at these institutions, cantorial certification remained closed to women until at least the 1970s.

Yet regardless, women played significant roles in postwar synagogue music programs, from regular participation in services, choirs, and social events, to spearheading national initiatives. Eisenstein and Ethel S. Cohen were deeply involved in the establishment of national “Jewish music” week/month programs starting in 1947, annually involving hundreds of concerts and new commissions of both liturgical and non-liturgical Jewish music works. Cohen’s ESCO Fund, meanwhile, underwrote musical exchange programs with Israel as well as foundational Jewish liturgical music publications by Alfred Sendrey, Solomon Rosowsky, and Johanna Spector. In 1950, Tziporah Jochsberger established the Hebrew Arts School, which focused on the Jewish music and dance education of young people. Nationally recognized composers such as Miriam Gideon (1906-1996) and Eda Rapoport (1890-1968) created liturgical music for liberal congregations that appeared as readily in the concert hall as in the sanctuary.

Postwar Liturgical Leadership

Congregations also appointed women to musical leadership positions during this time, though rarely with clerical titles. Thus, when in 1955 Temple Avodah in Oceanside, New York, appointed Betty Robbins to the position of cantor, the press at the time described Robbins as the first woman congregational cantor. Evidence suggests, however, that other women held similar responsibilities without the formal title.

By the early 1970s, with cantors employed at a sizeable minority of synagogues, new sources of liturgical music began to emerge from young composers seeking to engage peers and young families through “creative liturgy.” Prominent among these young composers was Debbie Friedman (1951-2011), who premiered her first service Sing Unto God in May 1972 with her former high school choir at Mount Zion Temple in St. Paul, Minnesota. At the end of the summer, Chicago’s Sinai Temple hired her as an artist in residence, where over the next two years she composed additional services and collaborated with modern dancer Nana Shineflug. Soon Friedman and her colleagues would connect to a growing Jewish education movement, including the Coalition for Alternatives/Advancement in Jewish Education (1976-2009), that saw music as an important means for instilling Jewish knowledge and commitment. This meeting point of education and spiritual leadership also helped spur a growing number of music leaders who direct their efforts to both children and adults, including Leah Abrams, Judy Caplan Ginsburgh, Fran Avni, Julie Silver, and Ellen Allard.

Women also started their own Jewish spiritual collectives beginning in the 1970s, looking to the intersection of Judaism and feminism to rethink Jewish tradition, congregation, and prayer. New rituals, including Women’s Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seders, The new moon; the first day of the month; considered a minor holiday, especially for women.Rosh Hodesh groups, and the Simchat Chochma (“Joy of Wisdom”) ceremony, all called for new music, which singer/songwriter/spiritual leaders such as Rabbi Shefa Gold, Rabbi Hanna Tiferet Siegel, Rabbi Geela Rayzel Raphael, Debbie Friedman, and Cantor Linda Hirschhorn provided. These movements also gave rise to musical groups such as MiRaJ and Vocolot, as well as numerous private and published song collections.

In 1975, meanwhile, Barbara Ostfeld became the first woman invested as a cantor by the Hebrew Union College School of Sacred Music (Reform) and inducted as a member of the American Conference of Cantors. Nine years later, Erica Lippitz and Marla Rosenfeld Barugel were accepted into to the Cantors Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (Conservative) and permitted to prepare for ordination as hazzan [cantor], which they achieved in 1987. The Cantors Assembly, associated with the Conservative movement, began accepting women into its membership three years later. Community acceptance happened gradually, as professional cantorial organizations, individual congregations, and rabbis initially treated women as a cantorial subcategory, and sometimes subjected them to biases around vocal range and lifecycle needs. By the turn of the twenty-first century, however, women had been largely normalized in liberal Jewish cantorial roles, comprising a majority of students in major cantorial programs, regularly serving as instructors and coaches, and assuming leadership positions in professional cantorial organizations. Some ordained cantors, including Angela Warnick Buchdahl and Alison Wissot, also received rabbinic ordination to affirm their status as religious authorities. In 2011, moreover, the Hebrew Union College School of Sacred Music was renamed for Debbie Friedman (1951-2011) and Cantor Nancy Abramson became Director of the Conservative movement’s H. L. Miller cantorial school.

At least two national organizations promote women’s religious Jewish musical leadership. The Women Cantors’ Network, founded by Cantor Deborah Katchko Gray in 1982, began as a group of twelve women serving as cantors or seeking that professional goal. Katchko Gray typified those who needed such an organization. Granddaughter of an eminent European cantor, most of whose family had perished in the Holocaust, she was trained privately by her cantor father. She secured a full-time active position at a Conservative congregation in Connecticut but felt isolated from the male cantorate. Joining her in spearheading the network was another privately trained cantor, Doris Cohen, formerly a liturgical soloist with composer and conductor Sholom Secunda, who served at a Reform pulpit in New York City. The network created a support group with annual study conferences, an extensive website, a music commissioning program, and publications that disseminate the work of dozens of members. Significantly, the network welcomed all women interested in musical leadership, regardless of musical training. As of 2021, the organization counts an international membership exceeding 300.

Hava Nashira, an annual conference-turned-organization based at the Olin-Sang-Ruby Union Institute in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, was founded in 1992 by Debbie Friedman, Jeff Klepper, and Jerry Kaye. Created around more recent practices of religious song leading, it provided a welcoming space for mentoring and training a wide variety of Jewish musical leaders, including summer camp-based music specialists, cantors, and synagogue musicians. In some ways a counterpoint to historically gendered cantorial training, Hava Nashira fostered the musical careers of many women by promoting inclusivity, a wide-ranging approach to worship, and openness to a wide breadth of religious Jewish music.

These and other programs have substantially increased women’s presence as creators of Jewish sacred music, especially where concepts of formal composition are less central. Whereas only two women won the Guild of Temple Musicians’ Ben Steinberg Young Composers’ Award between 1991 and 2018, for example, women comprised about 45% of creators in the six festivals held by the Shalshelet Foundation for New Jewish Liturgical Music between 2004 and 2016.

Women who sought greater public participation in Orthodox-identified prayer settings, meanwhile, created additional opportunities around the turn of the twenty-first century. Encouraged by opinions by rabbis Mendel Shapiro (2001) and Daniel Sperber (2003) that accepted women reciting certain prayers and reading the Torah in public, women helped to establish partnership minyanim; each group negotiated its own practices for integrating men’s and women’s voices in public worship. All-women’s prayer groups also expanded as places for collective spiritual expression.

The landscape of women’s musical spiritual leadership continues to vary from community to community, often combining ritual, education, and composition. Professional facilitators such as Basya Schechter, Shira Kline, Laurie Akers, Eliana Light, and Deborah Sacks Mintz offer new music and spiritual musical paradigms through both local and national gatherings and organizations such as the Rising Song Institute. At least anecdotally, women continue to comprise the majority of choristers, choir directors, and music educators in Jewish religious settings.

Yiddish Music

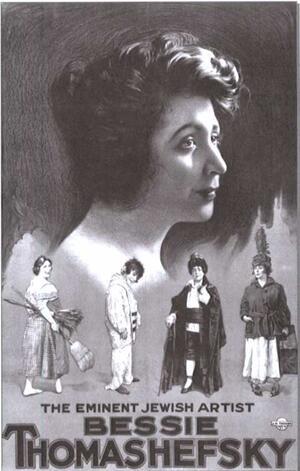

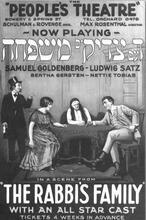

From the earliest American manifestations of Yiddish-language opera and operetta in the 1870s, women played central roles as writers, performers, and organizers. In America, actor/singers such as Sophie Karp (1861-1906), Regina Prager (1874-1949), Bertha Kalish, Bessie Thomashefsky, Celia and Stella Adler, Jennie Goldstein, Nellie Casman, and Molly Picon drew audiences as headliners and gained fame on both sides of the Atlantic through posters, recordings, film, and sheet music. Although men held nearly all composer and lyricist credits for this genre, there are enough credits to women, including Picon, Casden, and Goldstein, to suggest a greater creative contribution than those written attributions suggest.

Contrasting with largely male Yiddish folklore scholars in Europe, American women became significant scholars and disseminators of Yiddish folksong, from Leah Rachel Yoffie’s work in St. Louis in the 1910s and 1920s to singer Elizabeth Gutman’s contemporary inclusion of Yiddish folksong selections in recordings and concerts. The vast collection and scholarship efforts of Ruth Rubin, Eleanor Mlotek, and Irene Heskes, moreover, established an intellectual foundation that reached substantial audiences through a combination of lay presentation and academic erudition.

The Yiddish music revival starting in the 1970s radically reconfigured this scene, as new generations of women sought to reclaim the Yiddish repertoire in a manner that connected theater, folksongs, leftist politics, and new Yiddish linguistic identity. Much klezmer music initially appeared to code as male in the early years of the revival, following an illusory stereotype that “tradition” relegated women to singing or dancing roles. Countering these perceptions and forcing a gendered reckoning in the field were Lori Lippitz, who founded the more gender-balanced Maxwell Street Klezmer Band in Chicago in 1983; instrumentalists such as Alicia Svigals, Elaine Hoffman Watts, Susan Watts, Adrienne Cooper, Lauren Brody, and Ilene Stahl, who became distinguished bearers of Yiddish instrumental traditions on violin, drums, trumpet, accordion, and clarinet respectively; and the all-women klezmer groups Isle of Klezbos and Mikveh, both founded in 1998. These players and groups in turn mentored successive generations of women klezmer instrumentalists through both personal interaction and annual gatherings such as KlezKamp and KlezKanada.

Women also comprised the vanguard of Yiddish vocalists and educators, learning through both family experience and established culture bearers such as Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman, Ruth Rubin, Chana Mlotek, Bronya Sakina, and Ethel Raim. From Judy Bressler, an early vocalist with the Klezmer Conservatory Band, through next-generation performers such as Sarah Gordon and Amanda (Miryem-Khaye) Siegel, women singers formed multigenerational lineages, which in turn empowered them to master and transform their inherited styles. Gordon, for example, started the power-pop group Yiddish Princess with fellow Yiddish musician Michael Winograd in the 2010s.

Women and Music in American Sephardi Populations

Women also curated music in American twentieth-century communities descended from Jews of the Middle East, Asia Minor, the Iberian Peninsula, and North Africa. The field of Judeo-Spanish song has a strong historical association with women’s practices. As ethnographic studies by Kay Shelemay and others show, however, even in communities where women did not perform music in public, they sometimes sang in family or community settings, had a strong knowledge of repertoire, and remained important keepers and transmitters of musical tradition. Such has been the case with practitioners of Syrian music pizmon traditions and Sephardic songs, both of which saw their own American revivals in the late twentieth century. Another example was Los Angeles-based Emily Sene, who kept an extensive recording archive of her husband, singer Isaac Sene, from the mid-twentieth century (currently kept at UCLA).

As “Sephardic music” began to emerge as its own genre in the 1950s, artists connected to folk and early music began to record and perform songs gathered from archives, published collections, and elders. In 1958, Folkways Records released New York-born singer/author Gloria Levy (Kirchheimer)’s album “Sephardic Folk Songs,” comprising material she had learned from her Alexandria-born mother “in time-honored tradition.” In the 1970s, Judith Wachs (1938-2008) and other musicians associated with Marleen Montgomery’s Quadrivium early music collective created the group Voice of the Turtle, which became into one of the nation’s premiere Sephardic music ensembles; Wachs developed much of the group’s repertoire from her research in Israeli folk song archives. Bosnia-Herzegovina-born Flory Jagoda (1923-2021), whose 1983 composition “Ocho Kandelikas” became a Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah standard in America, composed and recorded numerous songs that reflected her Judeo-Spanish upbringing near Sarajevo before World War II. Prominent scholar-performers Judith R. Cohen, Galeet Dardashti, Vanessa Paloma Elbaz, and Simone Salmon each coupled careful ethnographic research with creative performance; along with many other performers, including Sarah Aroeste, they presented women’s voices in critical dialogue with both personal and communal ideas of heritage and tradition, and connected to a rising academic and cultural interest in Sephardic Studies.

American Art Music

In art and classical music, American Jewish women shared advances and handicaps with the general population of women in the United States. Until the latter part of the nineteenth century, American Jewish women faced the same limitations as the entire middle-class female population, that is, an embrace of amateur musical ability but wariness about professional aspirations. The first feminist movements in the United States, powered in large part by the campaign for suffrage, supported women’s struggle for a more public role in music as well as in other fields and promoted professionalizing music education. As a result, in the late nineteenth century, women in music began moving into public life and professional endeavors in increasing numbers. Training in voice and piano often comprised a significant part of Jewish women’s socialization into middle-class American society. Nineteenth-century sheet music offers evidence of male composer/teachers dedicating new compositions (especially dances) to their female students, likely denoting a patronage relationship. Women also brought their musical abilities to benefit concerts and literary afternoons, supported by synagogues and Jewish centers, where they performed vocal and piano works amid a broader array of speeches and debates.

Many of the Jewish women who pursued professional careers were singers. Most of first generation of Jewish American opera singers were born in Europe, including Lina Abarbanell, Alma Gluck, Julie Rosewald, Henrietta Sulzer, and Maria Winetzkaja. American-born Estelle Liebling also had a short career in opera, combining the advantages of fine European training with birth into a professional artist-musician family; after returning from European musical training in in 1902, she made her debut at the Metropolitan Opera and later toured extensively as a soloist with John Philip Sousa’s band, before concentrating on teaching voice.

Two singers born early in the twentieth century who had brief careers in opera but chose to be lieder and concert singers were Ruth Kisch-Arendt and Jennie Tourel. Both maintained personal and professional interests in Jewish affairs: Tourel became an ardent and musically active supporter of Israel, teaching and performing regularly in that country, and Kisch-Arendt, as noted earlier, headed the music department at the Stern College for Women.

Singers born after World War I who had notable careers in opera include Regina Resnik (1922-2013), Judith Raskin (1928-1984), Roberta Peters (1930-2017), and Beverly Sills (1929-2007). Sills, born Belle Silverman, appeared on radio beginning at age four, started her long years of study with Estelle Liebling at age seven, and began her professional singing career at sixteen. Her long and illustrious career as an opera prima donna and remarkable singing actor included a directorship of the New York City Opera, presidency of Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and chair of the Metropolitan Opera from 2002 to 2005.

Women have held professional instrumental performance careers in smaller numbers, partly due to the gender biases of the concert world. Socially constructed gender roles limited others, including pianist Hephzibah Menuhin (1920-1981), sister of violinist Yehudi. Both brother and sister made their first successful public appearances at age eight; however, their father concentrated on promoting his son’s career, while Hephzibah, who wished the same support and opportunity, was told that her sphere was home and children. A second sister, Yaltah (1921–2001), had even less of a performing career.

Among pianists, the earliest Jewish woman to have an international concert career was Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler (1863-1927), who was also an early American star on the international concert circuit. Other pianists followed from the 1920s onward, including Gertrude Lightstone Mittelmann (1907-1956). Nadia Reisenberg had an international career as a concert pianist. She first studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in her native Russia, where she made her debut. In 1922, she immigrated to the United States, where she studied at the Curtis Institute with Josef Hoffmann. Her performing career included appearances with major orchestras and ensembles in Europe and the United States. Chicago-born Rosalyn Tureck came from a musical immigrant family who provided her with fine teachers. At sixteen she won entry to the all-scholarship Juilliard School and soon after her debut established her reputation as a Bach specialist with an international career. Others of that generation include Ray Lev and Lonnie Epstein; in the next generation was Ruth Meckler Laredo.

Whereas piano was the primary instrument for the nineteenth-century female amateur musician, the violin was less common among American middle-class women. However, the example of French violinist Camille Urso, who made her debut as a child prodigy in mid-century, together with the later influence of the women’s movement, finally changed the violin into an instrument that respectable girls and women might play. By the turn of the century, when the seven-year-old Vera Hochstein [Fonaroff] arrived in the United States, American women were making careers as concert violinists and as members of women’s string quartets and orchestras. A prodigy, Hochstein made her debut at age nine with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, then continued her training in England and the United States. In 1909, she became second violinist in the all-female Olive Mead String Quartet, one of the earliest all-female groups and considered among the finest in the country. Lillian Fuchs, born into a musical family in 1902, had first-rate conservatory training as a pianist and then as a violinist and was able to move into the mainstream of musical life in New York, joining her two gifted brothers in chamber music recitals. She was a member of the Perole String Quartet from 1926 to the 1940s, one of the first American women to break the gender barrier in quartet playing.

Playing in professional orchestras and ensembles of all kinds, in concert halls, theaters, and cabarets and for radio and television has been the main source of musicians’ livelihoods. Yet women were for many years locked out of these positions. Their first reactions to such discrimination took the form of all-women groups, beginning in the late nineteenth century and coming to a high point between 1925 and 1945, when dozens of such orchestras were active from New York to California. Blanche Bloch (1890-1980) had the advantage of concertizing with her husband, a violinist, beginning with his debut in 1913. She also taught piano, the only other option open to most pianists. However, in the 1930s, Bloch found a niche as pianist in the New York Women’s Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Antonia Brico. The concert career of Eudice Shapiro (1914-2007), the daughter of a violist and the granddaughter of a cantor, was aided early by a solo engagement with the New York Women’s Symphony Orchestra, with whom she played the Sibelius Violin Concerto in 1938. Some of the women trained in orchestra playing in the all-women groups moved into positions vacated by men during World War II. A few were able to remain after the war was over, beginning the long struggle to integrate community, regional, and in recent years, major national American orchestras.

American women composers have had an even longer struggle than performers for recognition, whatever their religious background. Composers who enter the professional music field first as performers have a distinct advantage. Mana-Zucca (born Augusta Zuckerman, 1885–1981) was a composer as well as a pianist and singer with an extensive performance record, including appearances with major orchestras. She created a large oeuvre that mixed lighter compositions, such as the song “Big Brown Bear,” with more serious works, including concerti for piano and violin; of her Jewish-themed compositions, “Rachem” (Op. 60, #1 [1919]) became a standard of sorts in the cantorial solo repertoire. Jeanne Behrend, trained at the Curtis Institute of Music, also combined composition with piano performance and was recognized early for her creative gifts. However, she stopped composing in the 1940s because of neglect of her music by others.

Not all composers were also performers. Marion Bauer, whose earlier works were considered modern, continued composing almost until her death. Born in Walla Walla, Washington, to immigrant French-Jewish parents, Bauer was especially important for her championing of modern music in books, lectures, and teaching and through her considerable support of organizations such as the League of Composers.

By the late twentieth century, the number of women composers had increased exponentially and included such outstanding artists as Vienna-born Vally Weigl (1889–1982) and the American Miriam Gideon (1906-1996). Born in Greeley, Colorado, Gideon earned an M.A. in musicology from Columbia University and a Doctor of Sacred Music degree from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. She wrote orchestral and instrumental works, but compositions with texts predominate in her oeuvre. Gideon taught for many years at the City College of New York, the Manhattan College of Music, and the Cantors Institute of the JTSA. Vivian Fine (1913-2000), composer and pianist, wrote for modern dancers Martha Graham, Hanya Holm, Charles Weidman, and José Limón, in addition to opera, chamber, solo instrumental, and vocal genres. Ruth Schonthal (1924-2006) and Ursula Mamlok (1923-2016), both born in Germany, made their ways by circuitous routes to the United States in the 1940s. Schonthal’s style reflected her European background, while Mamlok combined serial techniques with more lyrical and eloquent writing. German-born Trude Rittmann (1908-2005), meanwhile, earned special renown as a composer, Broadway arranger, and conductor. The growing roster of notable composers whose oeuvres include Jewish-themed works includes Judith Berman, Lauren Bernofsky, Coreen Duffy, Sharon Farber, Vivian Fine, Andrea Clearfield, Barbara Harbach, Andrea Jill Higgins, Judith Karzen, Lillian Klass (d. 1986), Kelly-Marie Murphy, Shulamit Ran, Benjie Ellen Schiller, Judith Shatin, Elizabeth Swados (1951-2016), Meira Warshauer, and Judith Lang Zaimont.

Jewish women also held important organizing roles in the American musical avant garde movement. Minna Lederman (1896–1995) and Claire Raphael Reis (1888–1978), working with Marion Bauer, worked as publicists for the International Composers Guild in 1921, then in 1923 for the League of Composers. Lederman edited the League of Composers’ journal, Modern Music, and in the process taught a group of modern composers, Aaron Copland among them, how to write about music. Another patron, Minnie Guggenheimer (1882–1966), was famous for her support of the summer concerts at Lewisohn Stadium in New York and her cheery welcome to audiences during intermissions.

American Jewish music has expanded vastly in variety, range, and quality of activities. Jews brought to America their secular-folk and sacred-liturgical musical heritage. There has been a renascence of age-old traditions that have become means of self-expression for Jewish women. Religious freedom in the United States has been nourishing to Jewish women’s creativity as they increasingly make their marks as composers, organists, singers, instrumentalists, educators, and patrons. Indeed, they are integral to what constitutes an extraordinarily rich American musical environment. Yet positions of musical leadership remain complicated: Noreen Green and Judith Clurman remain among the very few women who have sustained decades-long careers directing professional Jewish orchestral and choral groups respectively (in addition to other ensembles), while Caroll Goldberg, Coreen Duffy, and Eleanor Epstein are among those who have maintained distinguished positions directing high school, college, and community choruses.

The aggregate view becomes clearer on the website for the Milken Archive of Jewish Music: The American Experience (founded 1990), a multi-million-dollar project to record and chronicle American Jewish (mostly art) music. As of November 2021, women represented 46% of featured singers (38 of 83), 22% of instrumentalists (11 of 51), 8% of composers (15 of 191), and zero out of twenty-eight conductors. These numbers offer one reflection of the historical perspective and contemporary landscape of “Jewish music” performance in the twenty-first century. Women comprise a higher percentage of more recent Jewish music projects, including 32% (8 of 25 as of November 2021) of the Composers Group for the Los Angeles-based Max Helfman Institute for New Jewish Music (founded 2010).

Negotiating Musical Spaces and Genres

In other American musical communities, Jewish women have negotiated between genre-based expectations of talent and creativity: sometimes signaling Jewish identity through specific choices in recordings and appearances, sometimes receiving public identification from Jewish fans seeking to identify with popular artists, and sometimes contributing to Jewish communal organizations

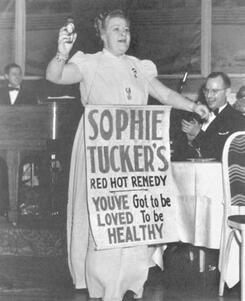

Since the early twentieth century, the growing popular music industry offered opportunities to women, both as singer/entertainers and as instrumentalists. “Torch singers” such as Sophie Tucker (1886-1966), Belle Baker (1893-1957), and Libby Holman (1904-1971) recorded songs of great emotion in both Yiddish and English, while jazz singer and musical theater actor Sylvia Syms (1917-1992), the daughter of an immigrant father, became one of the outstanding club singers of the next generation. Sylvia Fine, Dorothy Fields, and Betty Comden (among others) had outstanding careers as lyricists in popular music, theater, and film.

During World War II, women jazz musicians formed their own groups, most notably the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, in order to work and grow as artists. One recording group included Rose Gottesman, drums; June Rotenberg, bass; Mary Lou Williams, piano; Mary Osborne, guitar; and Margie Hyams, vibraharp. Rotenberg was an early crossover artist who later became a member of the New York City Opera Orchestra. On radio, Phil Spitalny’s All Girl Orchestra featured “Evelyn [Klein] and her Magic Violin.” Klein had graduated from the Institute of Musical Art in New York in 1931.

By the late 1950s, a variety of Jewish women found success in various parts of the popular music industry. Eydie Gorme (1928-2013), an outstanding popular singer from a Sephardic family, became famous as a recording artist and as half of a radio duo with her husband, Steve Lawrence. Barbra Streisand’s star turns as Jewish characters in the musicals I Can Get it For You Wholesale and Funny Girl began a career that coupled her vocal, acting, and directorial talents with regular references to Jewish identity (including, later, the 1983 film Yentl and the regular inclusion of Max Janowski’s song “Avinu Malkeinu” in her sets). Carole King, middle-class and college-educated, became a much-honored singer and songwriter, and subject of the 2014 Broadway musical Beautiful. And Cass Elliot (1941-1974) negotiated solo singing with her work in the folk-rock quartet the Mamas and the Papas.

The folk revival of the 1960s and 1970s, meanwhile, included notable contributions from Jewish women who often connected with earlier labor and left-wing movements, including Sally Fingerett and Malvina Reynolds (1900-1978). Max[ine] Feldman (1945-2007), who later identified as gender-fluid, proved a key figure in the women’s music movement.

Other prominent Jewish women who developed careers in the folk, rock, and punk scenes include Janis Ian, Regina Spektor, Jill Sobule, Lisa Loeb, and the indie-rock trio Haim. All openly identified, sometimes playfully, with their Jewish backgrounds: Loeb, for example, wrote the theme song to the second Shalom Sesame series (2010-2011), and Haim toured Jewish delis to promote its acclaimed 2020 album Women in Music Pt. III.

Near the turn of the twenty-first century, new initiatives to reinvigorate Jewish identity among young people, including John Zorn’s Radical Jewish Culture initiative and artist development programs such as the Six Points Fellowships, gave some women opportunities to craft Jewish musical worlds and distinctive voices that (selectively) crossed genres. Artists such as Shelley Hirsch, Ayelet Rose Gottlieb, and Jewlia Eisenberg (1971-2021) incorporated their personal Jewish backgrounds and identities into broader performing careers. Alicia Jo Rabins and Basya Schechter, meanwhile, pursued multimodal careers that included leadership roles in Jewish religious settings.

In gender-separated settings, women continued to foster their own music and performing arts culture, establishing solo careers, forming all-women ensembles and girls’ choirs/a cappella groups, and producing music videos, musical theater performances, and DVDs/streaming musical films for women-only audiences. Bands such as Bulletproof Stockings, PERL, and the New Moon All Stars Party Band, and singers such as Chanale [Chana Felig], Bracha Jaffe, Chaya Kogan, Chani Levy, and Shaindel Antelis reflected openly on matters of interest among women and girls in these communities. They disseminated their music through live performances and social media-based recordings; occasionally male singers recorded and performed their songs. Some artists also created public channels on sites such as YouTube, adding language that made viewers responsible for maintaining community religious standards.

Reconsidering the Past and Looking Forward

As the #MeToo/#GamAni movement gained momentum in the 2010s, both artists and community leaders opened spaces for reckoning with allegations of abuse and mistreatment of women by prominent (thus far all male) Jewish musicians. One of the most public accountings involved Shlomo Carlebach (1925-1994). Although stories had circulated since Carlebach’s death, including a 1998 article in Lilith magazine, #MeToo amplified the discussion and moved groups such as New York’s Central Synagogue and the Jewish Orthodox Feminist Alliance to call for temporary or permanent bans of his music. Neshama Carlebach, his daughter and a prominent musician in her own right, participated in several ongoing conversations addressing this complex legacy. Inquiries in liberal movements have identified other abusive musicians, often named only after their deaths; institutional responses have emphasized a process of “t’shuvah” (healing) among those still living, while seeking new organizational reporting procedures to address future incidents more effectively.

The twenty-first century has also seen greater gender diversification within some Jewish musical settings. LGBTQ+ synagogues and Yiddish circles have openly embraced gender-queer musical participation since the 1970s; more recently the Debbie Friedman School of Sacred Music began identifying students by voice part rather than gender. The broader implications of this shift in addressing gender-based musical choices, genres, boundaries, histories, and practices are continuing to emerge.

Adelstein, Rachel. “Braided Voices: Women Cantors in Non-Orthodox Judaism,” PhD Thesis, University of Chicago (2013).

Block, Adrienne Fried, and Carol Neuls-Bates. Women in American Music: A Bibliography of Music and Literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979.

Gordon, Dale. “A New Song: Feminism, Music, and Voice in Partnership Minyanim,” MA Thesis, Tufts University (2012).

Cohen, Judah M. “Professionalizing the Cantorate—and Masculinizing It?: The Female Prayer Leader and Her Erasure from Jewish Musical Tradition.” Musical Quarterly 101.4 (2018).

Heskes, Irene. The Music of Abraham Goldfaden: Father of the Yiddish Theater. Cedarhurst, NY: Tara Publications, 1990.

Heskes, Irene. Passport to Jewish Music: Its History, Traditions, and Culture. Cedarhurst, NY: Tara Publications, 1994.

Heskes, Irene. Yiddish American Popular Songs, 1895 to 1950. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1992.

Hetko, Adah R. “Lineage, Language, and Community Commitment: Contemporary Yiddish Women Singers and their Development of Yiddish Identity.” MA Thesis, Indiana University (2018).

"Nuptials at the Jewish Synagogue.” Alexandria Gazette and Advertiser LVIII, #101 (1857), 2.

Pendle, Karin, ed. Women and Music: A History. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Koskoff, Ellen. Music in Lubavitcher Life. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Rosenfeld, Lulla Adler. Bright Star of Exile: Jacob Adler and the Yiddish Theatre. New York: Shapolsky Publishers, 1986.

Ross, Sarah M. A Season of Singing: Creating Feminist Music in the United States. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 2016.

Rotem, Tamar. “Morality Plays.” Haaretz, January 7, 2005.

Salmon, Simone. “Emily Sene’s Sephardic Mixtape.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/emily-senes-sephardic-mixtap….

Sandrow, Nahma. Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

Shelemay, Kay “The Power of Silent Voices: Women in the Syrian Musical Tradition.” In Music and the Play of Power in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia. edited by Laudan Nooshin. New York: Routledge, 2009.

Slobin, Mark. Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immigrants. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1982.

Tick, Judith. “Women in Music.” In The New Grove Dictionary of American Music, Vol. 4, edited by H. Wiley Hitchcock and Stanley Sadie. London: Macmillan, 1986.

Vaisman, Ester-Basya (Asya). “‘Hold On Tightly To Tradition’: Generational Differences in Yiddish Song Repertoires Among Contemporary Hasidic Women.” In Choosing Yiddish, edited by Lara Rabinovitch, Shiri Goren, and Hannah Pressman. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2013

Wise, Isaac Mayer, “Does the Canon Law Permit Ladies to Sing in the Synagogue?” The Israelite II, 5-6 (1855).