Theater in the United States

Since the 1860s, Jewish women have been involved in the American theater as writers, actors, directors, designers, dramaturgs, critics, and scholars. A number of women played important roles in the Yiddish theater that thrived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, leaving a rich legacy that is still carried on today. In the twentieth century, actors from Sophie Tucker and Fanny Brice to Barbra Streisand and Bette Midler shaped American theater, while writers contributed to both musical and nonmusical theater. In the last decades of the century, figures such as Judith Malina and Liz Swados rocked the foundations of the theater establishment. In the twenty-first century, an increasing number of Jewish women artists have embraced activism, confronted social issues, and explored personal history as part of the work of theater.

For over 150 years, Jewish women have been involved in the American theater as actors, writers, directors, producers, designers, dramaturgs, critics, and scholars. The vitality of the Yiddish theater, the splendor of Broadway, the rich tapestry of the regional theater, culturally specific Jewish theaters—and everything in between—all owe a debt to the Jewish women who have given of their talents, their energy, their drive, and their dreams. From the classical performances of Rose Eytinge in the 1860s to the radical experiments of Judith Malina in the 1960s and the exuberant explorations of Paula Vogel and so many other women working in the twenty-first century, Jewish women have made in the American theater opportunities to express themselves, to challenge audiences, and to take the art of theater to new heights.

The Nineteenth Century

Actors

In the nineteenth century, two major stars of the American stage claimed a Jewish identity. The great French actor Sarah Bernhardt made her American debut in 1880 as the tragic title character in Adrienne Lecouvreur. In her nine tours of America, she astounded audiences with her tragic grandeur and majestic passion.

Audiences often flocked to theaters to follow their favorite stars, and Rose Eytinge proved a notable attraction. She performed with such luminaries as Edwin Booth, touring major cities, performing for President Lincoln, even visiting the White House. Of her performance in Rose Michel (1875), one critic said that she “attained to the exalted pitch of perfect truth, in delineation of horror and agony, and it swept to this apex with the spontaneity of perfect ease.” Her fierce, dark passion thrilled audiences, and although she seems to have concealed her ethnicity, she was often described as “the black-eyed Jewess.” She left an autobiography that describes her experiences on the stage, as well as her work with Booth and another major Jewish theater dynasty, the Wallacks.

While Bernhardt and Etyinge became known for their more classical roles, Adah Isaacs Menken became best-known for her sensational performance in the melodrama Mazeppa (1861). At the climax of the action, the villains strapped her “nude” body (clad in a body stocking) to the back of a horse that was then driven over the edge of a cliff. One enraptured critic described her as “the sensation of the New York stage,” adding, “Her rare beauty and the tantalizing audacity of her performance defy description. She must be seen to be believed; anyone who misses her at the Broadway Theater will be denying himself the rarest of exhilarating treats.” The truth of Menken’s background remains obscure. She may have converted to Judaism at the time of her first marriage. Rumors also circulated that she boasted Black heritage. However, as scholars Daphne Brooks and Renee Sentilles have noted, Menken shared so many conflicting stories about her antecedents that discerning the accurate version becomes difficult. Nevertheless, she remained devout until the time of her death, regularly writing in defense of Jewish rights and publishing articles, stories, and poems in prominent Jewish newspapers, such as Cincinnati’s The Israelite.

Other women of Jewish descent working as theater artists at this time (the Wallacks, the Nathans circus family, Isabella Mordecai, Mrs. Solomons and her two daughters) have become largely invisible in the historical record, though a few traces remain. Jewish women would become much more visible on the Yiddish stage in the second half of the nineteenth century.

The Yiddish Theater

With the great wave of Jewish immigration in the late nineteenth century, the Yiddish theater in America thrived. In a broad range of styles, from lively musical revues to intellectual avant-garde performances, the Yiddish theater offered a center of community life for many Jewish immigrants. It provided entertainment and education. It was a way to feel a sense of belonging in a strange place, to understand life in a new world, and to preserve the culture of the homeland. It symbolized a first step on the bridge between being foreign and being American. With a rich and vast legacy to the English-language theater, it also served as a conduit for new European plays, cultivated a community of passionate theatergoers, and produced an array of fine actors whose influence is still felt today.

Sara Adler was genuine Yiddish theater royalty. First married to actor Moische Heine-Haimovitch and later to flamboyant Yiddish theater impresario Jacob P. Adler, she was known for her dark beauty and the depth of her emotional power. The great Yiddish playwright Jacob Gordin wrote several plays especially for her, including Without a Home (1907), in which she played an immigrant woman who ultimately goes mad because her husband and son adjust to American life while she fails. Sara Adler’s achievements—along with those of Yiddish actors such as Bertha Kalich, Esther Kaminska, and Keni Liptzin—contributed to the recognition of Jewish women as serious actors on the American stage. Her daughter Stella Adler built on her mother’s accomplishments and went on to change the face of acting in America.

Celia Adler, daughter of Jacob Adler and his second wife Dina Shtettin Feinman, appeared in the Yiddish theater from childhood and became a founding member of the Jewish Art Theater, dedicated to the new trend toward realism in drama, a literary repertoire, serious rehearsals, and professional directors and designers. In contract negotiations, she turned the spotlight on the difficulty faced by a woman alone in a business dominated by and designed for men. And while her long, rich career was built almost exclusively in the Yiddish theater, she was among the first of the serious actors to appear in an English-language production on Broadway.

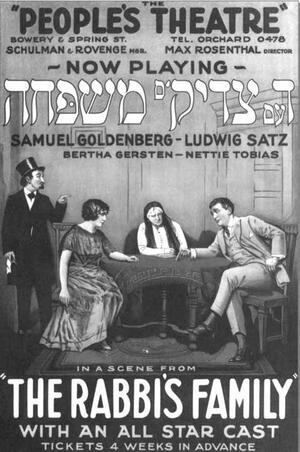

Actors such as Berta Gersten and Bertha Kalich dedicated themselves primarily to the Yiddish theater but found success on the English-language stage as well. So did the charming Molly Picon, whose first major role in the English-language theater was in the Broadway production of Sylvia Regan’s Morningstar.

These women of the Yiddish theater left a rich legacy and set an example of strong, entrepreneurial artists that is still carried on today. While the days of dozens of Yiddish plays running on 2nd Avenue in New York City have passed, the Klezmer and Yiddish revival that began in the 1960s and the resurgence of the Yiddish theater company Folksbeine, along with the tremendous success of Paula Vogel’s Indecent, reflect a renewed interest in Yiddishkeit and culture among theater practitioners and audiences. However, it remains important to note that there were probably also Jewish women directors, managers, and designers whose contributions to nineteenth-century theater were not recorded. In the English-speaking theater, women may have hidden their ethnicity because of antisemitism and discrimination. Theda Bara offers an example of a Jewish American woman who became famous on stage and screen in the earliest part of the twentieth century as the original sexy “vamp” seductress but whose Jewish background remained obscure to many fans. In fact, this supposedly exotic heroine, reportedly from Egypt or some other similarly exotic locale, had been born Theodosia Goodman, the daughter of a Jewish tailor who emigrated from Poland to Cincinnati.

The Twentieth Century

Actors

In burlesque and vaudeville, some Jewish women adopted the conventions of Black performers, including the genre known as “coon shouting.” Scholars such as Alison Kibler have explored the reasons Jewish performers sometimes appropriated Black identities in particular as a means of deflecting critiques about their own ethnic heritage. Belle Baker found vaudeville success by playing the sexualized image that white audiences associated with Black women. Louise Dresser employed a chorus of Black children in her act, in a way integrating her show for the first time. Sophie Tucker (née Sonya Kalish from Ukraine) admired Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, and the Black blues singers and wanted to sing like them. Like many vaudeville and burlesque performers of the time, she began her career wearing blackface and singing songs in dialect—she was billed as “the red-hot mamma.” As she found success, she shed some of these external trappings and performed more frequently as herself, albeit with an assimilated name, and her biggest hit was “My Yiddishe Mama.”

Fame, if not fortune awaited those lucky enough to be chosen for the Ziegfeld Follies, which included Sophie Tucker, Belle Baker, Nora Bayes, and the incomparable Fanny Brice. Born Fania Borach in New York’s Lower East Side, Brice proved a natural mimic with a sharp sense of humor and an excellent singing voice. Although early in her career she tried to appear less “ethnic” by changing her name to Brice, she found early on that it was her comic specialty numbers—such as Irving Berlin’s “Sadie Salome, Go Home,” sung with a Yiddish accent despite the fact that she did not speak Yiddish—that won her audiences. A certain kind of ethnic humor, based largely on stereotypes, remained popular on the twentieth-century American stage, and Brice rode this wave to stardom.

For many Jewish stars on Broadway, their success seemed to depend on the degree to which they could downplay their Jewishness. Trained for a career in opera, Vivienne Segal made her early career playing the ingenue in musicals such as Oh, Lady! Lady! (1918) and The Desert Song (1926), later returning to Broadway in the roles of sultry older women in shows such as Pal Joey (1952) and A Connecticut Yankee (1943, 1952). Libby Holman was an alluring torch singer who appeared on Broadway in Garrick Gaieties (1925). The superb comedienne Judy Holliday made her New York debut in Kiss Them for Me (1945), became a star with her portrayal of mob moll Billie Dawn in Born Yesterday (1946), and earned a Tony award for her turn as the meddling telephone operator in Bells Are Ringing (1956).

Productions in the first part of the twentieth century often lacked the cohesive production elements that contemporary audiences have come to expect. In 1931, a group of committed young theater artists, including Stella Adler, chose to forge their own path. Theirs would be a theater that valued content and form, where artists were continually nurtured in the development of their technique, and where technique was used to express a shared response to the world around them. The Group Theatre, founded in 1931, dedicated itself to training and nurturing actors and to building a sense of ensemble performance in which everyone contributed equally to the success of a production. Together, they explored the methods of Russian acting teacher and director Konstantin Stanislavsky, developing an approach to acting that emphasized spontaneity and emotional authenticity. In response to the Group’s first production, one reviewer claimed enthusiastically, “Jaded Broadway seems finally to have found the young blood and new ideas for which many of us have been praying.”

Despite the success, Stella Adler grew dissatisfied with the company’s acting methods. She wanted techniques that were more reliable, more tangible, and less personally intrusive, so she took up the matter with the great Stanislavsky himself when she met him in Paris in 1934. Intrigued by Adler’s boldness, the master invited her to study with him. “He understood,” said Adler later, “that asking the actor to recall his personal life could produce hysteria, so he had abandoned that. He believed now that the actor must rely on his imagination.” Adler recorded the sessions in her diary over the six-week period that she and Stanislavsky worked together, and she shared her findings with the members of the Group Theatre upon her return to America.

The results of Adler’s work with Stanislavsky significantly altered the Group’s approach to acting. Although these ideas were never fully embraced by founder Lee Strasberg, the dynamic tension between Adler’s understanding of Stanislavsky and that of Strasberg resulted in some of the finest ensemble performances ever recorded in the American theater. In Clifford Odets’ Awake and Sing and Waiting for Lefty, the ideals of the Group Theatre were magnificently realized.

In 1949, Adler carried her work forward by founding the Stella Adler Conservatory of Acting where, until her death in 1992, she trained generations of up-and-coming actors, including Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, Ellen Burstyn, Elaine Stritch, and many others. Stella Adler’s high standards, her passion for excellence, her willingness to challenge the status quo, and her love of theater itself inspired and influenced a vast array of actors, directors, and acting teachers. This indomitable Jewish American woman, daughter of Yiddish theater royalty, changed American acting fundamentally and forever.

Barbra Streisand, a different and wholly original star, dominates the discussion of Jewish performing artists from the late 1960s and brings the twentieth century full circle. As the klutzy Miss Marmelstein in I Can Get It for You Wholesale (1962), she introduced her own brand of energy, brass, and humor to the Broadway stage. But it was Streisand’s portrayal of Fanny Brice in Funny Girl that made her a star. After years of seeing Jewish actresses hide their Jewish identities, seeing Jewish characters played by non-Jewish people, or participating in the reduction of Jewish characters on stage or film to stereotypes either shrewish or silly, Streisand simply performed her Jewish self. She did not change her name or her nose. Her upbringing was Jewish—she neither flaunted nor hid it. She played herself—sexy, hilarious, outrageously talented, ambitious, and outspoken. Her work moved with spectacular success to film (as a director, actor, producer, and singer). Her impact still resonates in the United States theater, as more women feel free to perform their authentic selves, speak their minds, and empower other women.

Writers

American Jewish playwrights, composers, and lyricists, women as well as men, have contributed their talents to the Broadway stage in abundance. Dorothy Fields was a lyricist and librettist whose work is best known for fresh turns of phrase and zesty humor. She wrote the lyrics to such popular songs as “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” and “On the Sunny Side of the Street” and librettos for popular shows such as Annie Get Your Gun (1946) and Sweet Charity (1966). Even after her death, her lyrics were featured on Broadway in productions of Ain’t Misbehavin’ (1978) and Sugar Babies (1979).

Bella Spewack and her husband Sam were one of Broadway’s best-known writing teams. Together they wrote twelve plays—mostly madcap comedies and social satires—including Boy Meets Girl (1935), the book for Cole Porter’s Tony Award–winning musical Kiss Me Kate (1948), and My Three Angels (1953).

The team of Betty Comden and Adolph Green won fame on Broadway for fast-paced, wisecracking lyrics and librettos. They wrote On the Town (1944) with Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins, Wonderful Town (1953) with Leonard Bernstein, and Bells Are Ringing (1956) with Jule Styne. Their partnership proved to be one of the longest and most successful in Broadway history, continuing through Applause (1970) and Singin’ in the Rain (1985).

Among the significant American Jewish writers of the nonmusical Broadway theater are a host of great women, including Edna Ferber, Rose Franken, Sylvia Regan, and Lillian Hellman. Ferber was a celebrated novelist as well as an acclaimed playwright, known for her keen ear for dialogue and her sharp wit. She created her great Broadway successes in collaboration with George S. Kaufman: Minick (1924), The Royal Family (1927), Dinner at Eight (1932), and Stage Door (1936). Two of her novels were made into popular Broadway musicals: Showboat (1927) and Saratoga (1959).

Novelist and short story writer Rose Franken crossed over into the theater with the surprise hit of her play Another Language in 1932. Her sharp-eyed observations about the American family gave tang to her domestic dramas Claudia (1941) and The Hallams (1947). Social concerns such as antisemitism, homophobia, sexism, and war fueled her other plays such as Outrageous Fortune (1943), Doctors Disagree (1943), and Soldier’s Wife (1944).

Sylvia Regan served as the press agent for Orson Welles’s Mercury Theatre before she made her mark as a Broadway playwright with the 1940 production of her Jewish family drama Morningstar, featuring Molly Picon and Sidney Lumet. In 1953, she topped her earlier success with the production of her comedy about the garment industry, The Fifth Season.

No discussion of American playwrights—male or female, Jewish or gentile—would be complete without Lillian Hellman. Like her male counterparts Clifford Odets and Arthur Miller, Hellman expressed through her plays a strong belief in ethics, morality, truth, and responsibility. The Children’s Hour (1934)—Hellman’s drama about the destructive power of a lie—won her the accolades of critics, who called her a “second Ibsen” and “the American Strindberg.” In tightly constructed, powerful dramas such as The Little Foxes (1939), Another Part of the Forest (1947), The Autumn Garden (1951), and Toys in the Attic (1960), Hellman took audiences on rigorous emotional journeys and left them drained, horrified, uplifted, angry, sorrowful, but never bored.

Wendy Wasserstein’s success marked a turning point for Jewish women in American theater. Wasserstein wrote plays for and about women and, unlike Hellman, she did not hide her Jewish identity behind bland de-ethnicized character names and vague attempts to make characters’ family backgrounds seem generically American. Wasserstein’s Jewish characters are unabashedly Jewish. Yet Wasserstein’s wit and her off-kilter insight into the experiences of contemporary American women made her plays appealing to audiences regardless of their ethnicities. In plays such as Uncommon Women and Others, Isn’t It Romantic?, and The Heidi Chronicles, she claims her identity as a white Jewish American woman. The Sisters Rosensweig deserves special attention, as characters navigate their relationships to Judaism and Jewishness in very distinct ways, not presenting a monolithic version of Jewishness, Judaism, or Jewish women. The character of “Gorgeous,” so brilliantly played by Madeline Kahn in the premiere, blows all the dust off a narrative put in place for Jewish women—she will not be confined by the role of mother or temple sisterhood member, she will not be humiliated for lighting her SabbathShabbat candles, she demands to be seen as a full person, not a stereotype. Wasserstein offered a complete, empathetic, hilarious version of Jewish womanhood.

Designers

As a young woman, Aline Bernstein planned to put her artistic abilities to use as a portrait painter, but the lure of the theater turned her into a costume and scenic designer. At the Neighborhood Playhouse, she designed The Little Clay Cart and The Grand Street Follies (1924). On Broadway—in addition to her work on Grand Hotel (1930)—she is remembered for her designs for Lillian Hellman’s powerful dramas The Children’s Hour and The Little Foxes.

When Jean Rosenthal went to work for the Federal Theatre Project in 1935, the formal role of lighting designer had yet to evolve in the complex position of contemporary theater. Rosenthal helped to develop the lighting designer’s role. She saw the power of light to evoke mood, draw focus, and express ideas. Her lighting design for Orson Welles’s production of Julius Caesar (1937) brought her to prominence, and she went on to design extensively for modern dance pioneer Martha Graham. Rosenthal also designed such well-known Broadway productions as West Side Story (1957), Hello, Dolly! (1964), and Fiddler on the Roof (1964).

Producers

Producers wield extraordinary power in commercial theater in the United States. Although it is a field largely dominated by men, Jewish women have taken on the challenge with savvy, drive, a passion for quality, and a knack for leadership. Helen Menken, for example, turned her substantial energy to producing after a successful career as an actor. She is best known as producer of the Stage Door Canteen, Broadway’s contribution to the war effort from 1942 to 1946, and served as president for many years of the American Theater Wing, the organization responsible for Broadway’s top honor: the Antoinette Perry Award (the Tony).

One of the most important American theater producers of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s was Theresa Helburn, president of the Theatre Guild. She spearheaded Guild efforts to raise the artistic level of Broadway production, to present challenging plays in the commercial theater, to build audience support, and to nurture the work of talented theater artists. The Guild’s achievements include legendary productions of plays by Elmer Rice, John Howard Lawson, Robert Sherwood, Maxwell Anderson, and Eugene O’Neill. Helburn was responsible for pairing the popular acting couple Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne (1924), for bringing Oklahoma! to the stage (1943), and for producing Othello with Paul Robeson (1943).

Irene Mayer Selznick—daughter of MGM founder Louis B. Mayer and the wife of producer David O. Selznick—learned about producing from some of the best in the business and went on to produce A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), Bell, Book and Candle (1950), and The Chalk Garden (1955). Wrote New York Times drama critic Mel Gussow, “When she produced Streetcar and other plays, she worked hand in glove with the playwright in insuring that the work was seen absolutely to its best advantage.”

Visionaries, Iconoclasts, and Rule Breakers

During the turbulent 1960s, virtually every aspect of American society was called into question, including the theater. Among the most influential experimental groups was the Living Theatre, a collective founded by Jewish American actor/director Judith Malina and her husband Julian Beck. Originally devoted to producing the poetic works of writers such as Federico Garcia Lorca and Gertrude Stein, the company’s aesthetic began to evolve with its hyper-realistic productions about drug addiction (The Connection) and the rituals of life in a military prison (The Brig). However, the Living Theatre truly found its style in 1963, when the company went into exile in Europe to avoid taxes. Intrigued by the radical acting theories of Antonin Artaud, Malina and Beck developed a unique performance style that sought to shatter the restraints of realism, break down the boundaries between audience and performer, blur the distinction between art and real life, and create a communal ritual experience of the moment. Critic Robert Brustein wrote, “By stirring up a kind of theatrical anarchism wilder than anything that has been seen here or abroad, the Living Theatre has literally given life to theater.” They returned to the United States in 1968 and, at Brustein’s invitation, presented four spectacular performances at Yale University—Mysteries and Smaller Pieces, Antigone, Frankenstein, and Paradise Now—that bedazzled, enraged, and inspired audiences. Especially provocative was Paradise Now, Brustein recalled, at the end of which “everyone was exhorted to leave the theater and convert the police to anarchism, to storm the jails and free the prisoners, to stop the war and ban the bomb, and to take over the New Haven streets in the name of the People.”

Other Jewish American women rocked the foundations of the theater establishment as well. Playwright Susan Yankowitz scripted the Open Theater’s landmark 1969 production of Terminal and lent her bold imagery and avant-garde sensibility to works such as The Ha-Ha Play, Slaughterhouse Play, and Boxes. Rosalyn Drexler skewered sex and violence in satires such as Home Movies and The Line of Least Existence. And Karen Malpede wrote Lament for Three Women, The End of War, and Making Peace even as she co-founded the New Cycle Theater in Brooklyn. Liz Swados wrote the remarkable musical Runaways, which transferred to Broadway in 1978, and she is well remembered for her collaborations with artists at Ellen Stewart’s La MaMa Theatre, where she composed music for some of the most important experimental productions, including Peter Brook’s Conference of the Birds.

In the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s and 1970s, theater companies began to emerge with the mission of supporting artists of specific ethnic and cultural backgrounds, exploring ethnic and cultural identity, and creating theater based on that exploration. New theaters devoted to the American Jewish experience sprang up in this creative climate, including American Jewish Theater and Jewish Repertory Theater in New York and A Traveling Jewish Theater in San Francisco, followed by Theatre J in Washington, DC, and Theatre Or in Denver in the 1990s. Indeed, throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, many Jewish theaters (often housed at JCCs) were established to varying degrees of success.

Actor/director Naomi Newman, together with Corey Fischer and Albert Greenberg, founded A Traveling Jewish Theater “out of a desire to create a contemporary theater that would give form to streams of visionary experience that run through Jewish history, culture, and imagination.” In brilliantly evocative productions, using masks, puppets, music, movement, sound, and silence, A Traveling Jewish Theatre has explored a range of concerns, including isolation, exile, and assimilation. And when Naomi Newman takes the stage in her play Snake Talk: Urgent Messages from the Mother, she speaks to the very heart with passion and eloquence. Theatre J operates in much the same spirit and has become among the most controversial and successful Jewish theaters. It expanded its repertoire beyond the boundaries of Jewish writers, choosing to trouble the very notion of what is a Jewish story, often at odds with its own audiences and the JCC in which it is housed.

Dreaming of a Regional Theater—and Making It Happen

As early as the 1920s, Jewish women recognized that there was an American theater beyond New York. Outside professional structures, in community and regional drama groups, in art theaters and little theaters all over the country, theater was being created purely for the love of the art. Often this work celebrated community, bringing people together in the collective experience of producing a play and providing opportunities for the community itself to share in the event. Jewish American critic Edith Isaacs, the influential editor of Theatre Arts magazine, referred to this kind of theater as “the tributary theater,” feeding the mainstream with a wealth of talent, energy, and ideas. She rejected the commercialism of the New York theater and called on Americans to go to “the four corners of the country and begin again, training playwrights to create in their own idiom, in their own theaters.” All over the country, people responded to Isaacs’s call, dedicating themselves to developing and nurturing a nationwide, grassroots theater movement.

One of those who took up the call was Zelda Fichandler. Like Isaacs before her, Fichandler rejected the commercialism of the New York theater. She saw the joblessness of American theater artists as a tragic waste of talent and the centralization of American theater in New York as a denial of the vast cultural potential of a diverse nation. “What was essentially a collective and cumulative art form was represented in the United States by the hit-or-miss, make-a-pudding, smash-a-pudding system of Broadway production,” said Fichandler. “What required by its nature continuity and groupness, not to mention a certain quietude of spirit and fifth freedom, the freedom to fail, was taking place in an atmosphere of hysteria, crisis, fragmentation, one-shotness, and mammon-mindedness.” Fichandler and two other pioneering women decided to create new theatrical models. In 1947, Margo Jones founded Theater 47 in Houston and Nina Vance founded the Alley Theatre in Houston, and in 1950, Zelda Fichandler founded the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C.

Fichandler surrounded herself with consummate professionals, including a skillful administrative and production staff and a dynamic company of actors, designers, and directors. She devoted her considerable drive, artistic vision, and business acumen to the success of the Arena Stage, giving classics by Oscar Wilde and Oliver Goldsmith a place alongside modern plays by Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams. In 1967, Fichandler produced Howard Sackler’s sprawling new play The Great White Hope, guiding the development of the play from its unwieldy original form into a powerful epic and giving it a strong production starring James Earl Jones. It proved a milestone production for Fichandler, Jones, and the Arena Stage.

Fichandler’s success inspired others. Soon, her Arena Stage was just one of a vast network of regional theaters all across the United States, including the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco, the Long Wharf in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Seattle Repertory Theater. In 1965, Ella Malin noted that regional theaters illustrate “the slow but growing acceptance of theater as a permanent cultural institution worthy of community support in much the same way as museums, libraries, and symphony orchestras.” Today, there are over three hundred nonprofit professional theater companies in the United States, consistently offering a broad range of high-quality productions and providing artistic homes to countless professional actors, directors, designers, technicians, and administrators.

Among those who followed in Fichandler’s footsteps are Emily Mann, artistic director of the McCarter Theater Center in Princeton, New Jersey; Libby Appel, artistic director of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland, Oregon; Sara Garonzik, producing artististic director of Philadelphia Theatre Company; Majorie Samoff, founding artistic producing director of the American Musical Theater Festival/Prince Music Theater; Meryl Friedman, artistic director of Lifeline Theater in Chicago; Carey Perloff, artistic director at American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco; Barbara Gaines at Chicago Shakespeare Theater; Susan Medak, managing director of Berkeley Repertory Theater in Berkeley, California; and Lynne Meadow, artistic director at the not-for-profit Manhattan Theater Club.

In the first few decades of the twenty-first century, American regional theater has provided fertile ground for the production of new plays by Jewish women, offering a supportive environment where plays can grow and change for artistic, rather than business, reasons. Emily Mann’s Annulla, An Autobiography premiered at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis; Barbara Damashek’s Quilters (cowritten by Molly Newman) was first presented by the Denver Center for the Performing Arts; Barbara Lebow’s A Shayna Maidel was developed at the Academy Theater in Atlanta and received its first professional production at Hartford Stage Company; and Wendy Wasserstein’s Pulitzer Prize–winning play The Heidi Chronicles was workshopped at Seattle Repertory Theater and later presented at Playwrights Horizons in New York.

The Twenty-First Century

The turn of the new century brought new challenges and successes for Jewish artists. New models of producing, new concerns about how to confront social issues, and a new embracing of personal history as part of the work of theater makers have come to the fore. While many Jewish artists have long supported unions, racial equality, and other social justice causes, an increasing number of women have embraced activism in the last several years.

Actors

Listing the accomplishments of Jewish actors from more recent times is a delightful impossibility, and many have experienced a shift in the freedom to be publicly Jewish. So many performers self-identify and celebrate their Jewishness. In the footsteps of Barbra Streisand, talented women such as Idina Menzel, Shoshana Bean, Shayna Blass, and Beanie Feldstein have kept their “Jewish” names proudly. Actors like Judith Light and Bette Midler ushered in a modern model of the artist activist in the 1990s and 2000s, particularly with their vocal support of LGBTQ+ issues. Natalie Portman (née Hershlag) began using her grandmother’s maiden name when she got her first acting jobs while still a child. She appeared on stage in The Diary of Anne Frank, Closer, and The Seagull. Portman is also known as an activist, and as an Israeli citizen she has shared a compelling and intelligent voice around issues surrounding Israel’s policies and politics. Like Portman, Debra Messing has been vocal about women’s issues. Comedian Judy Gold has been a force for women in comedy and outspoken on LGBTQ+ issues; her one-woman shows 25 Questions for a Jewish Mother and The Judy Gold Show: My Life as a Sitcom have toured the country. Jessica Hecht has maintained a strong theater career (including as Golde in Fiddler on the Roof) and created the Campfire Project, which traveled to make theater with Syrian refugees.

Many white Jewish performers have felt that being Jewish carried a sense of responsibility, feeling keenly the privilege they attained through assimilation into American society and wanting to extend such privilege to other communities. This activism has grown as urgent cries for anti-racist action in the theater have increased, in the face of the obstacles faced by so many artists of color, including Jews of color.

Writers

As with actors, a bounty of Jewish writers works in theater today. Writers such as Susan Miller, Sherry Kramer, Deb Margolin, and Eve Ensler continue to create provocative and important work. Lisa Kron, who has been creating theater since the late 1980s (most memorably the Five Lesbian Brothers), shared the 2015 Tony Award for best musical for Fun Home with Jewish composer Jeanine Tesori.

Among the women writers grappling with Jewish identity and representing Jewish causes onstage are Amy Hertzog, Karen Hartman, Emily Feldman, Zoe Kazan, Rinne Groff, Brooke Berman, Deborah Zoe Laufer, Sarah Gancher, Hailey Feiffer, Jenny Rachel Weiner, Jenny Lyn Bader, Mara Nelson-Greenberg, Zohar Tirosh-Polk, Lila Rose Kaplan, and Deborah Yarchun. Jennifer Maisel’s play Eight Nights was presented in coordinated performances across the country as a benefit for HIAS (formerly the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) in 2019.

Jewish American women including Amanda Green, Shaina Taub, Anaïs Mitchell, Rachel Sheinkin, Sarah Saltzberg, and Ella Rose Chary remain active in musical theater. Prolific and beloved songwriter Carole King saw her life reenacted on stage in the jukebox musical Beautiful, which was nominated in several Tony categories and won the 2015 Grammy for best cast album.

Paula Vogel’s drama Indecent (2015) has emerged as one of the most significant plays about Jewish identity since Tony Kushner’s Angels in America cycle. This “little, Jewish play” has been seen all over the country and was filmed for PBS. Vogel worked with director Rebecca Taichman to create it, inspired by Sholem Asch’s 1906 Yiddish play The God of Vengeance. Vogel first encountered Asch’s play in graduate school in the 1970s, and Taichman discovered it during her studies at Yale in the 1990s. Asch’s work had a complicated history; after playing all over the world in Yiddish, it moved to Broadway in 1923 with an English translation. Because of its content, which included discussions of prostitution and lesbianism, authorities closed it on opening night and charged the actors with indecency. Taichman had mined the court transcripts for her thesis project. In 2011, she and Vogel were commissioned by the Yale Repertory Theater and American Revolutions at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival to create a new work. For Vogel, as a lesbian in the 1970s, encountering this story of young women who fall in love in a play from 1906 was nothing short of revelatory. The play spans historical periods, from Warsaw in the 1900s, to New York in the 1920s, to the Łódź Ghetto in the 1940s, to Connecticut in the 1950s, in addition to directly addressing its present-day audience in the opening and closing moments. Vogel’s play represents more than a retelling of a landmark play about women who love each other. It shares an exploration of the role of the artist in the world and proclaims that art matters.

Indecent opened at Yale then moved to the La Jolla Playhouse in California and the Vineyard Theatre in New York; it marked Vogel’s arrival on Broadway in 2017. The Broadway and subsequent regional theater productions played out as antisemitic violence rose sharply and the United States government’s treatment of immigrants became an even more fraught topic. Indecent marked a powerful moment in Jewish theater-going history, as many in the companies and audiences saw the dangerous parallels to the censorship of a hundred years earlier and the shadow of the Holocaust itself. It was also profoundly moving to newer immigrants and immigrants from non-Jewish or non-gay backgrounds, who saw in it their own struggles represented on-stage. In a character like her version of Asch, Vogel asks us to see what the responsibility of an artist should be. The play also raises questions of what is the right—or safest—way to be a Jew, and what is the best way to succeed, or even just to survive. By presenting issues of high art vs. low art and the discrimination against newly arrived Eastern European Jews not just by WASP-ish Americans but also by their more assimilated Central European brethren, Vogel challenges assumptions about what and who we value, and why.

Directors

Rebecca Taichman had been known for her interest in Jewish stories from her time at Yale, with her People Vs. The God of Vengeance and The Green Violin (2003), a musical she created with Elise Thoron and Frank London about Marc Chagall and Solomon Mikhoels and the Moscow State Yiddish Theater. Her direction of Indecent was dazzling, both harnessing and letting fly Vogel’s script, which leaps through time and asks the actors to fall into multiple roles. The music director for the premiere was Lisa Gutkin, famous for her work with the Klezmatics. Taichman won the Tony Award for her direction, and Vogel was nominated for her script.

Other Jewish theater directors whose work has appeared on and off-Broadway are Susan Schulman, Anne Kauffman, Lila Neugebauer, Daniella Topol, Tina Landau, Leigh Silverman, Megan Sandberg-Zakian, Julie Taymor, Danya Taymor, and Rachel Chavkin. Chavkin’s highly collaborative work with her company TEAM has received a great deal of attention. She directed Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 (2014) and Hadestown (2016), both of which went to Broadway and earned her Tony nominations; she won for Hadestown. She has also been involved in political and social causes, including voter registration, the Ghost Light Project, created in the aftermath of the 2016 Presidential election, and more.

Many regional theaters and director training programs are led by women, such as Anna Shapiro (Steppenwolf and Northwestern), Shirley Serotsky (Hangar Theater, previously Theater J), Jessica Kubzansky (Boston Court), Pirronne Yousefzadeh (Geva), and Shana Cooper (Northwestern, previously at Woolly Mammoth and California Shakespeare Festival). Cooper’s regular collaborator is Jewish choreographer Erika Chong Shuch. Also in the dance theater world is Stephanie Crain Klemons, whose work has been seen on Broadway with If/Then and as the associate choreographer for Hamilton.

Yousefzadel and Sandberg-Zakian, among the founding members in 2017 of Maia, a collective of directors of Middle Eastern and North African descent, have also been leaders of conversations around diversity, equity, inclusion, and access in the general and the Jewish theater.

Designers

Jewish women, and women in general, are less represented in the design world. Legendary costume designer Ann Roth continues to be in demand after designing more than 100 shows over the course of her long career. She won the Tony for Best Costume Design for The Nance in 2013 and has been nominated ten more times. In 2019, she competed against herself for To Kill a Mockingbird and Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus. She won the Oscar for her work on The English Patient (1997). She also stands as a brilliant example of mentorship: her niece Amy Roth is a costume designer working in film and television.

Lighting designer Natasha Katz has won Tony Awards for Aida, The Coast of Utopia, The Glass Menagerie, An American in Paris, and Long Day’s Journey into Night, in addition to several nominations and other awards. She has served as a mentor with the Open Doors program of the Theatre Development Fund. Sibyl Wickersheimer, professor at the University of Southern California, is a much-sought-after set designer whose work has been seen all over the country and has been included in the Prague Quadrennial.

The world of New York producers is a small one. Jenny Gersten had a long career at Williamstown Theatre Festival as associate producer and later as artistic director. In addition to her work as a freelance producer on such shows as Beetlejuice, The Visit, and The Bridges of Madison County, she served as the executive director of an enormous parks project, the Highline, and is a consulting producer at the Perelman Arts Center. After working in new play development at the Center Theater Group and as the producing director at the McCarter Theater, Mara Isaacs launched Octopus Theatricals, which produces a wide array of work, ranging from experimental to commercial. She has achieved remarkable success in the last few years, including Tony winner Hadestown, by Anaïs Mitchell, directed by Rachel Chavkin.

Daryl Roth has been producing theater since the 1990s, including such successful and award-winning works as Anna in the Tropics, Caroline, or Change, War Horse, The Humans, and Kinky Boots. Having previously worked with Vogel on How I Learned to Drive, Roth came on as a producer for Indecent. When the show was going to close early in its run due to low ticket sales, Roth stepped in and gave it another chance. The show then ran for several more months.

In regional theater, Amelia Acosta Powell has produced for Arena Stage and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. She is currently the associate artistic director of St. Louis Repertory Company. Abby Marcus is the managing director at Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, after being in the same role for The Orchard Project. She also serves as creative producer for the Obie Award-winning company Vampire Cowboys.

Jewish women have also thrived in literary management and dramaturgy. Dramaturgy as a field has exploded since the 1990s, with many institutions hiring these experts in new play development, historical research, and contextualization. Practitioners such as Hannah Hessel-Ratner, Julie Felise Dubiner, Miriam Weisfeld, and Rachel Lerner-Ley have found themselves in various positions as freelancers and in regional theaters. Liz Engelman spent many years at Actors Theater of Louisville, the Intiman Theater, the McCarter, Hedgebrook, University of Texas/Austin, and more before starting her own artists’ retreat, Tofte Lake Center, in Minnesota. Ilana Brownstein similarly worked at the Huntington Theater and Boston University before co-founding and co-running the collectively organized Company One in Boston. Molly Marinik and Jess Applebaum were among the co-founders of Beehive Collective, a group of dramaturgs organized as a service venture.

Critics and Scholars

Jill Dolan and Stacey Wolf are performance studies scholars and feminist teachers at Princeton University; both are vitally important to the theater field. Dolan’s The Feminist Spectator as Critic is a foundational text in the field, and among her dozens of books and articles are her biography on Wendy Wasserstein and Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. Wolf’s Beyond Broadway: The Pleasure and Promise of Musical Theatre Across America is another important addition to the field. Wolf and Dolan also edited the 2011 TDR journal devoted to Jewish American performance. Barbara Grossman of Tufts University wrote the indispensable Fanny Brice biography Funny Woman. Heather S. Nathans of Tufts University has written about pre-Civil War representations of Jewish American identity in Hideous Characters and Beautiful Pagans: Performing Jewish Identity on the Antebellum American Stage. Debra Caplan of Baruch College has written the award-winning Yiddish Empire: The Vilna Troupe, Jewish Theater, and the Art of Itinerancy. Magda Romanska, dramaturg and professor based at Emerson College, has edited several books on dramaturgy, dramatic criticism, performance studies, and theater philosophy. Choreographer and teacher Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process has become the foundation for engaging with audiences about performance.

Contemporary Challenges

The question of defining what constitutes “Jewish” or “Jewishness,” particularly onstage, continues to challenge Jewish theater. Many of the artists referenced here are profoundly secular, of mixed heritage, and do not always create specifically Jewish theater. Many artists continue to grapple with the Holocaust, as the last survivors pass away and audiences face modern reminders of genocide. Conflicts about Zionism and Israeli/Palestinian theater have also proved difficult to navigate, and the political climate in the United States often makes collegiality difficult to maintain. As a result of the #MeToo movement, a number of Jewish men in the theater industry have been exposed as sexually and emotionally abusive.

Antisemitic acts and violence on the arts have also been profoundly discouraging. For example, at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Shana Cooper’s production of Indecent went into rehearsal just a few months after the murders of Jews in Poway and Pittsburgh. This production of Indecent was also the first to include Jews of color (Rebecca S’Manga Frank and Bill DeMerritt), who faced racism from the audience, including from white Jews, who questioned their Jewishness. Indeed, many portrayals of Jews on stage remain based on a white, “Ashkenormative” idea of Jewishness, even though it has been 25 years since Wasserstein’s An American Daughter featured an observant Black Jew, Dr. Judith Kaufman. Today, reflecting the demographic changes in America and the American Jewish community, a growing number of performers garnering acclaim are Jews of color including Frank, Demerritt, Nicolette Robinson, and Daveed Diggs of Hamilton (And “I Want a Puppy for Hanukkah”) fame. But questions about representation of Jews on stage and screen continue, especially about who gets to be Jewish on stage. Indecent’s success created more opportunity for Jews to be Jews in theater. Indeed, many involved in productions of Vogel’s play remark that it was the first time they got to be Jewish for a play; for Jews of color, this is even more significant.

Newer companies like the Jewish Plays Project, a competition and development initiative, and theatre dybbuk, a company committed to Jewish performance and education, have begun to offer more opportunities for Jewish artists to make positive change in the theater. HowlRound and American Theatre magazine have recently published articles on Jewish themes and questions. There are also new spaces for observant Jews to be able to practice their art, such as 24/6, a theater that honors Shabbat, and the training program Kol Neshema, founded by Robin Garbose, which invites girls and women to study theater and film with a Torah perspective.

Stella Adler’s question of almost a century ago—how artists can practice their craft in ways that will do less harm to themselves and others—continues to resurface. Intimacy Direction has emerged as a new field within theater, and Jewish women including Sarah Lozoff, Rachel Flesher, and Maya Herbsman are rising in prominence as this new collaborative role committed to physical and emotional safety becomes more common.

Questions about how Jewish American artists work have risen to the forefront as people emerge from the forced shutdown of the COVID-19 pandemic and the cries for justice and equality that reverberated so profoundly after the murder of George Floyd and many other people of color. During the pandemic shutdown, many institutions reckoned with a powerful document issued in 2020 by a collective of theater artists entitled We See You, White American Theater. Among the signers are a few Jews of color. It has been a time of difficult conversations and anti-racist work, which sits alongside the work to improve conditions and increase opportunities for women. Rachel Chavkin’s impassioned 2019 Tony speech captured the feeling of many artists: “There are so many women who are ready to go. There are so many artists of color who are ready to go. And we need to see that racial diversity and gender diversity reflected in our critical establishment, too. This is not a pipeline issue. It is a failure of imagination by a field whose job is to imagine the way the world could be.”

No one article can encompass the entire history of Jewish American women’s contribution to theater in the United States. For example, trans artists, stage managers, and agents and managers are not included, and certainly many actors, writers, directors, designers, and more have been missed. Despite great progress, many women have had no choice but to hide their Jewishness, and even today some feel that stinging tradition lingers. Theater, though, has provided space to so many Jewish women, who have contributed their many talents, pushing the art of the theater to greater heights and giving strength and depth to its intellectual and creative foundations. They have written great plays. They have performed onstage with skill, strength, and sensitivity. They have been innovators in lighting, costume, and scenic design. They have directed productions. They have challenged and inspired with their critical writing. They have founded and run their own theater companies. And they have nurtured talent as teachers. Jewish women have been there from the beginning, they have performed with distinction, and they will continue to do so.

Adler, Stella. The Technique of Acting (1990)

Bigsby, C.W.E. A Critical Introduction to Twentieth Century Drama (1985)

Bordman, Gerald, ed. Oxford Companion to American Theatre (1992)

Brock, Pope. “Stella Adler: The Fiery First Lady of American Acting.” People Weekly 32, no. 3 (July 17, 1989): 66

Brustein, Robert. Making Scenes: A Personal History of the Turbulent Years at Yale, 1966–1979 (1984), and The Third Theatre (1970)

Chinoy, Helen Krich, and Linda Walsh Jenkins, eds. Women in American Theatre (1987)

Clurman, Harold. The Fervent Years: The Story of the Group Theatre and the Thirties (1957)

Cohen, Sarah Blacher, ed. From Hester Street to Hollywood: The Jewish-American Stage and Screen (1986)

Croyden, Margaret. Lunatics, Lovers and Poets: The Contemporary Experimental Theatre (1974)

Goldman, William. The Season (1970)

Guernsey, Otis L. Curtain Times: The New York Theatre, 1965–1987 (1987)

Hewes, Henry. Saturday Review (December 30, 1967): 18

Lifson, David S. The Yiddish Theatre in America (1965)

Lynes, Russell. The Lively Audience: A Social History of the Visual and Performing Arts in America, 1890–1950 (1985)

Malin, Ella A. “The Season around the United States with a Directory of Professional Regional Theatres.” The Best Plays of 1965–1966 (1966): 42

Malina, Judith. The Diaries of Judith Malina, 1947–1957 (1984)

Neff, Renfreu. The Living Theatre: USA (1970)

Picon, Molly, and Jean Bergantini Grillo. Molly! (1980)

Sandrow, Nahma. Vagabond Stars: A World History of Yiddish Theater (1977)

Schiff, Ellen. Awake and Singing: Seven Classic Plays from the American Jewish Repertoire (1995), and Fruitful and Multiplying: Nine Contemporary Plays from the American Jewish Repertoire (1996)

Sherin, Edwin. “In the Words of Edwin Sherin.” Cue (May 24, 1969): 15

Theatre Profiles 9 (1990)

Wilmeth, Don B., and Tice L. Miller. Cambridge Guide to American Theatre (1996)

Zeigler, Joseph Wesley. Regional Theatre: The Revolutionary Stage (1973).