Jewish Radicalism and the Red Scare

Examine the rich tradition of Jewish radical politics and its repression in the McCarthy era, focusing on the history of Jewish radicalism in the entertainment industry and the Hollywood blacklists of the 1940s and 1950s.

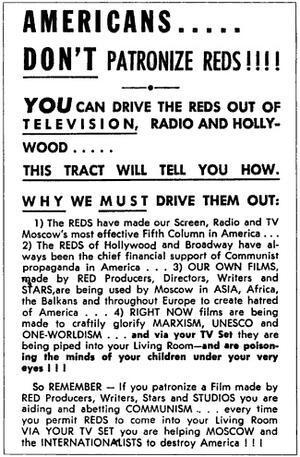

A black and white advertisement from the mid-1950's describing the dangers of supporting members of the Communist who work in the entertainment industry. By anonymous, via Wikimedia Commons.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

- American Jewish culture in the 20th century was shaped by radical politics and its backlash.

- American Jews in the entertainment industry shaped American popular culture in the first half of the 20th century.

Essential Questions

- What is the relationship between Jewish immigrants and radical politics in the early 20th century? Why were so many radicals Jewish?

- What was the role of radicalism in creating an American Jewish secular identity?

- What was the impact of McCarthyism on American Jewish secular identity?

- What was the role of Jewish creative labor in shaping American popular culture, such as the movie industry?

Materials Required

- Copies for each student of the Lesson 7 Introductory Essay

- Copies for each student of the Lesson 7 Document Study and Handout (optional)

- Technology set-up for showing film clips in the classroom, if this is not assigned as homework

- Technology for making videos, unless students will only write screenplays and perform them in class live

- Paper, pens, and markers for storyboards

- Costumes and props (may be brought in by students)

Notes to Teacher

This lesson explores the rich tradition of Jewish radical politics and its repression in the McCarthy era, focusing particularly on the blacklist of Hollywood writers. It also looks at how Jews, radical or not, represented a huge percentage of entertainment industry personnel and how that affected the content of Hollywood films, television and radio. Teachers will want to be particularly careful not to allow students to simplify the very complex ways in which the people involved in this period of history behaved. For example, while students may want to see informers as evil, teachers should help students to understand the very difficult choices people had to make, for instance deciding between speaking out about one’s religious or political beliefs and one’s ability to earn a living and maintain one’s reputation.

Please use the comments section at the bottom of the page to share what clips, scenes, YouTube videos or other film resources you use in this lesson with the rest of the JWA community.

The following biographies can be used in connection to this lesson:

Jewish Radicalism and the Red Scare: Introductory Essay

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy, Labor, Lesson 7

There is a strong tradition of Jewish radicalism, which began in earnest in the late 19th century. Some Jews became radicals in Eastern Europe, but many first encountered radical politics such as Socialism or Communism as immigrant workers in American cities. The Jewish radical community swelled after 1905 as Jewish immigrants fled persecution from the revolutions sweeping across Russia. In America, radical politics and the labor movement became new forms of Jewish expression—“purely secular” and “thoroughly Jewish” as activist Yankel Levin described it in 1918.[1] Jewish socialists saw themselves as creating a new model of the Jew: worldly, activist, and broad-minded. Yiddish culture, expressed both in political activities and in cultural forms (literature, theater, etc.), was at the center of this new Jewish world. From this cultural flourishing emerged a new image of the Jew as radical—an influential characterization during the Progressive Era.

Yet even in such an open political environment as the democratic society of the U.S., radicals have been persecuted in certain periods. This often occurred during or after wars or other periods of vulnerability; the 1920s, after the end of World War I, for example, saw the first “Red Scare,” an attack on Socialists, Communists, and labor organizers (named after the color of the flag of the newly created Soviet Union). Another Red Scare occurred after World War II, a period also referred to as the “McCarthy Era” after Senator Joe McCarthy who made his name pursuing and persecuting “Communist sympathizers.” From 1946 through the early 1960s, American citizens suspected of being sympathetic to the Soviet Union or Communism, or who were thought to have radical political views in general, were investigated, arrested, imprisoned, fined, fired from their jobs, and barred from future employment in their fields. People lost their careers, their friends, and sometimes even their families. Ordinary people were encouraged to spy on their neighbors and friends and to report any suspicions of “subversive” activity (any activity that could in some way be seen as undermining American political democratic and capitalist culture). This might mean saying something that sounded sympathetic to Communism or leftist politics, going to Communist Party (CP) meetings (it was not actually illegal to be a member of the CP), socializing with friends who were being investigated for Communist activity, etc.

Suspected Communists were pursued across society, but two areas in particular were considered fertile ground for finding Communist sympathizers: education and the entertainment industry. Increasingly educated and therefore no longer limited to work in the trades, Jews moved into white collar professions such as teaching and writing, and many became involved in unionizing these industries, just as they had the garment industry. Jews were frequent targets within these fields. Some 90% of the teachers “blacklisted” from working in the public schools in this period due to their alleged subversive activities were Jewish.[2]

Jews went into film, television and radio for the same reason many went into the garment industry earlier in the twentieth century: these were financially risky business ventures that weren’t already saturated by non-Jews. Jews were often closed out of businesses due to anti-Semitism, but at the start of first the film and then the television industries in particular, there was opportunity at all levels, from owning a production company to script writing to acting. Jews jumped into the void, and then brought friends and relatives with them.

Another path for many Jews into film, radio, and television was their experience in the Yiddish theater. From the time of the earliest large-scale Eastern European immigrations to the U.S. in the 1880s, Jews had established music and theater companies. While Yiddish theater wasn’t itself inherently politically radical, it was created by and performed for the working class Jewish immigrants whose political associations tended to be on the left of the political spectrum. When the motion picture industry was developing in the early twentieth century, many of the producers, directors, writers, and actors went into it directly from Yiddish theater.

Many, such as the actor Paul Muni and the director Edgar G. Ulmer, the latter whose financial backing came partly from the garment industry trade unions, made the move from New York to Hollywood with a stop on Broadway first. In Hollywood, they found a more open society in which they could both shed their immigrant personae and bring their Jewish influences and styles into the new popular culture they were creating. Ironically, Jews—who in some ways remained outsiders and were barred from certain kinds of social access (for example, quotas limited Jewish entrance into universities)—played a key role in shaping American culture. This also meant that Jewish culture began to permeate American culture, bringing certain stock Jewish characters, such as the guilt-inducing mother or the traditional, bearded Jewish rabbi, from the Jewish theater and into mainstream popular culture.[3]

As Nazism grew in Germany in the 1930s, eventually leading to the Holocaust and the military aggression that would become World War II, American Jews began to put pressure on the U.S. government to intervene on behalf of Europe’s Jews. Though it delayed entry into the war, the U.S. ultimately chose to ally with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. After the war ended, some politicians, such as Representative John Rankin, remembered Jewish lobbying for U.S. entry into the war, particularly by those in Hollywood making films sympathetic to the Soviet Union, and interpreted these efforts as a pro-Communist ploy. This led Rankin and others to conclude that Hollywood was a nest of Jewish Communist sympathizers. The Congressional hearings that were organized to root out Communist influence in Hollywood took particular interest in the role of Jews at all levels in the entertainment industry.

Jews were also particularly vulnerable to charges of radicalism in this period because of the high profile case of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Arrested in 1950 on charges of passing atomic secrets to the Soviet Union, the Rosenbergs were convicted and executed in 1953. The specter of McCarthyism and the execution of the Rosenbergs haunted a generation of Jewish radicals.

Some of those involved in the House Un-American Activities Committee (the Congressional committee charged with investigating subversive behavior) were overtly anti-Semitic. For example, Representative John Rankin was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and known for his blatant anti-Semitism toward fellow Congressmen. Many Jews suspected that HUAC chose to focus on Hollywood because of its large Jewish presence and the prominent role of Jews in building the studio system. Six of the “Hollywood Ten”—the ten original “unfriendly witnesses” (those who would not cooperate with HUAC’s demand that they identify Communists) indicted and imprisoned by HUAC in 1947—were Jewish. They were all blacklisted until the 1960s or 1970s.

The blacklist began when the Hollywood studios pledged not to hire anyone under suspicion by HUAC; while the film industry proclaimed outwardly that it did not have a blacklist, the television industry institutionalized their blacklist by creating specific procedures that determined whether or not a potential employee was suspected of Communist sympathy.[4] Being questioned by HUAC was sometimes all that was needed to be blacklisted, and many worked hard to get the Committee to write letters on their behalf so they could return to work. Those who could afford to sometimes hired “fronts” to put their names on blacklisted writers’ scripts so the writers could continue to make a living; this was obviously not possible for actors and directors.

There were those in the entertainment industry who cooperated with HUAC. Known as “friendly witnesses,” they agreed to identify people they believed to be Communists (referred to in shorthand as “naming names”), as director Elia Kazan did, or offer other information, as did the author Ayn Rand (see primary sources). While these “friendly witnesses” were able to continue to work in the industry, they often lost the respect of their peers. For example, when Elia Kazan won a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Academy Awards in 1999, nearly 50 years after his HUAC testimony, some members of the audience refused to stand and clap for him. Even the organized Jewish community cooperated with HUAC, checking the names on the list for accuracy to “protect” innocent Jews from questioning and possible indictment, and in the case of the American Jewish Committee, developing a strategy of counter-propaganda to positively influence Americans’ attitudes toward Jews. [5]

Not all of those blacklisted considered themselves Communists or even sympathizers. While some were former members of the Communist Party and many considered themselves politically leftist, others said they associated with Communists mainly for social rather than political reasons. The screenwriters were known especially for their membership because the Party had a writers’ group many attended for the companionship, given their lonely occupations. The screenwriters had also already drawn considerable animosity for their leftist leanings during tense union negotiations in the 1930s and 1940s. But particularly after Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected, those who had identified with Communist or Socialist values had thrown their support to his New Deal and become Democrats.

In 1972, director Adrian Scott, the last of the more than 300 blacklisted artists, was able to return to work using his own name. Once their names were cleared, many who had been blacklisted and had not been fronted (meaning, had their work submitted by a “front” whose name appeared on their work and who took a cut of the pay for “fronting”) were still unable to get work because they hadn’t published anything for over twenty years. Others had to continue to work under their pseudonyms or the names of their fronts because they were unknown by their real names.

Footnotes:

[1]Tony Michels, A Fire in their Hearts: Yiddish Socialists in New York (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 179.

[2]American Social History Project, Who Built America? Working People & The Nation’s Economy, Politics, Culture & Society, Volume Two: From the Gilded Age To The Present (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), 503.

[3]“The Social Film and the Hollywood Blacklist,” Dave Wagner, 37-59 in Buhle, Paul, ed., Jews and American Popular Culture, Volume 1: Movies, Radio and Television (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2007), 37, 48.

[4]Bowie, Steven W., “Intellectual Pogrom: How the Blacklist Purged Political and Cultural Discourse in Early Television,” pp.199-211 in Buhle, Paul, ed., Jews and American Popular Culture, Volume 1: Movies, Radio and Television (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2007), 201.

[5]Navasky, Victor S., Naming Names (New York: The Viking Press, 1980), 124.

Evaluating Arguments Using Primary Sources

Have students read the Lesson 7 Introductory Essay, and be sure that students understand the following points, many of which are covered in the essay:

- The McCarthy era was very difficult for individuals who were targeted by government policies. There were no right or wrong ways for people to behave when they had little control over their fates regardless of the actions they took.

- Students should understand what the House Un-American Activities Committee did.

- Jewish organizations (i.e. American Jewish Committee) worked in different ways to protect American Jews during the period.

- The Soviet Union had been allied with the U.S. during World War II and then immediately after the War, the U.S. Government identified it as an enemy.

- Individuals whom the government targeted as radicals identified with radical politics in different ways and for different reasons.

Distribute the document study to the students, and have them work in small groups to read the documents and answer the accompanying questions. Then, using the Lesson 7 Worksheet Jewish Radicalism: Why or Why not?, students should generate two lists in response to the questions:

- Why did some Jews join or ally themselves with the Communist Party? Why did Jews feel that affiliating with and/or protecting the Communist Party was important even when they were attacked by the U.S. Government?

- Why did some Jews speak out against the Communist Party and its supporters? What reasons might American Jews or Jewish immigrants have had to support the House Un-American Activities Committee’s actions against radicals and Communists?

Scripting Blacklist History

Students will write screenplays describing the history of Jewish radicalism in the entertainment industry, the persecution of Jewish creative talent by the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee, and the blacklists in the 1940s and 1950s. These screenplays should be geared to a 7th–12th grade audience, and they can be in the form of the documentary or as “dramatized” through one of the genres listed below.

Jewish filmmakers during the first half of the 20th century used the genres of science fiction, horror, romance, comedy, war, and the musical to make movies that reflected on the American Jewish experience and which sometimes portrayed left-leaning political perspectives. For example, The Jazz Singer, made in 1927, depicted a young, Jewish cantorial student being forced to choose between the life of a synagogue cantor or as a popular singer. On the one hand, he would be doing what was expected of him by his father’s immigrant generation; on the other, he would be leaving behind the traditions to become an assimilated American Jew. Another example is Frankenstein, made in 1931, in which the “monster” might be a metaphor for the sympathetic and misunderstood Jew.

Below is a partial list of films by genre.[1] Choose one or two of each genre to show students clips, so they can get a feel for the dialogue and atmosphere. Alternatively, you might break students into groups to look at clips in small groups, or assign clip viewing for homework. Be sure the versions of these films that you and your students choose are from the first half of the 20th century.

A caution: these movies were released before there was a rating system, so it is important for teachers to know the content of the films, as well as to have viewed her/himself any films if the teacher is showing the film clips in the classroom. For example, some of the subject matter and images of the horror films, in particular, may be inappropriate for the classroom.

Prepare students by telling them that these film clips may appear very unsophisticated to their 21st century eyes, but these films are significant because they were made by Jews, with Jewish actors, and about issues of concern to Jews in the first half of the 20th century, such as civil liberties, the role of the immigrant in society, the plight of the working man, what it means to be American, the alienation of people perceived as out of the mainstream, and questions of “good” and “evil.” You may suggest that they pay particular attention to lighting, casting, and costuming so you can see examples of how movies looked and sounded at this time period. These clips are cultural documents that we can use as research when we are writing our own screenplays. Pay close attention to dialogue and how the actors speak as well as how sound, music, and lighting effects help to set the mood of the scene.

Have students work in small groups to first identify a topic for their screenplays. Alternatively, the class can brainstorm a list of topics based on the background essay and the primary sources for this lesson, and then break into small groups to do the writing. Topics might include: testifying before HUAC, the response of the Jewish community to McCarthyism, or the experience of being blacklisted.

Next, have students create storyboards in their small groups, either computer- or manually-generated. A storyboard is a series of rough sketches identifying the “action” that will take place in each scene of their screenplays. (For more information about storyboards, see this page from the Digital Animation Mentoring Program at Ohio State University.) A well-thought-out storyboard will show the arc of the plot, from exposition and rising action to climax and then resolution. Tell students that good film is created through conflicts that eventually force something to change so that the hero is different at the end from how s/he was at the beginning. Such tensions might be classified as “human against nature,” “human against society,” or “human against human,” for example.

Once the students have their storyboards worked out and approved by teachers, they can begin to work on the actual dialogue that will become their screenplays. Have them choose the genre in which they will tell the history, draft the screenplay, and then “test” a scene or two by acting it out or even just reading it aloud and then doing re-writes.

These screenplays can be “shot” with video cameras in the classroom or for homework. Encourage students to find appropriate costumes and props and to experiment with different kinds of shots and lighting. Alternatively, the students can write and perform plays, rather than screenplays, live in class.

Make a bunch of popcorn and watch each video or performance as a class, critiquing for historical accuracy as well as for depth and breadth of content. Referencing the chart of arguments made in Part 1 of the lesson for analysis of what each student video’s message about the era was will reinforce the depth of learning to be gained by watching the videos. And make sure everyone claps after each group’s presentation!

Possible Movies by Genre:

War

- Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939)

- All Quiet on the Western Front (1930)

- Edge of Darkness (1943)

Romance

- That Midnight Kiss (1949)

- Mr. Skeffington (1944)

- Abie’s Irish Rose (1928)

Horror

- Dracula (1931)

- Frankenstein (1931)

- The Devil-Doll (1936)

- Isle of the Dead (1945)

- The Black Cat (1934)

- The Most Dangerous Game (1932)

Musical

- The Jazz Singer (1927)

- Rhapsody in Blue (1945)

Footnotes

[1] The list of films cited was compiled from chapters in two books: Wagner, Dave, “The Social Film and the Hollywood Blacklist,” pp.37-59 in Paul Buhle, ed., Jews and American Popular Culture, Volume I: Movies, Radio, and Television (Wesport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2007) and Buhle, Paul and Dave Wagner, Radical Hollywood: The Untold Story of America’s Favorite Movies (New York: The New Press, 2002).

Jewish Radicalism and the Red Scare

Context

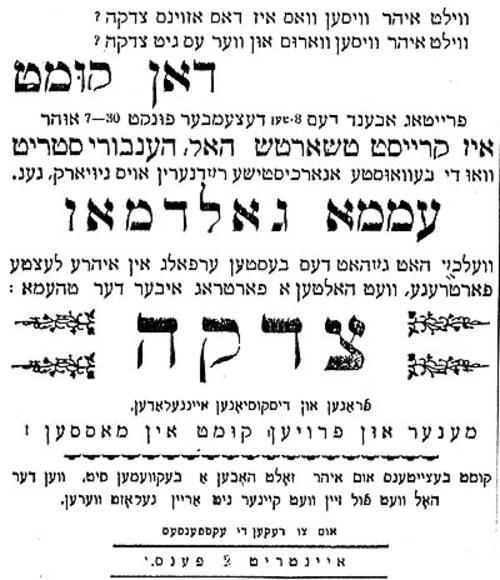

Emma Goldman was a Russian Jewish immigrant to the U.S. in the late 19th century. She was influenced by the Jewish secular Bundists in Russia, and she became politically radical—an anarchist—shortly upon her arrival in the U.S. Though Goldman was opposed to organized religion, she sometimes lectured in Yiddish and mentioned Jewish themes. The U.S. Government called her “the most dangerous woman in America” and she was ultimately deported in 1919 to the Soviet Union as an “alien radical.”

Emma Goldman Lecture on "Tzedakah," or Charity, December 1899

Courtesy of the Emma Goldman Papers.

Discussion Question

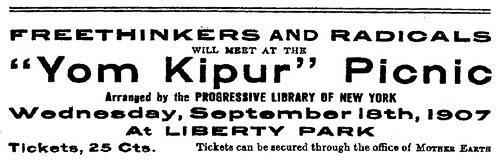

Advertisement for "'Yom Kipur Picnic" Organized by Emma Goldman and her Colleagues

Emma Goldman's non-traditional relationship to Jewish practice is evidenced by her participation in events such as this, scheduled on Jewish holy days.

Freethinkers and Radicals

Will Meet at the "Yom Kipur" Picnic

Arranged by the Progressive Library of New York

Wednesday, September 18th, 1907

At Liberty Park

Tickets, 25 cts. Tickets can be secured through the office of Mother Earth

Discussion Questions

- What do you think is the significance of having a picnic on Yom Kippur?

- What might a Jewish anarchist be saying about being Jewish by attending a Yom Kippur picnic?

- Why have the picnic on Yom Kippur specifically and not another day?

Context

Ayn Rand (originally Alisa Zinov'yevna Rosenbaum) was a Russian-American novelist, playwright, Hollywood screenwriter, and philosopher. Her philosophy, called Objectivism, rejected altruism in favor of self-interest and has been influential among Libertarians and some conservatives. Rand was called before HUAC to talk about the film Song of Russia. Producer Louis B. Mayer gave testimony saying the film was not meant as Soviet propaganda, and Rand, a witness “friendly” to the Committee, testified that it was absolutely propaganda.

Excerpt of Ayn Rand’s testimony before HUAC, October 20, 1947

McDowell: That is a great change from the Russians I have always known, and I have known a lot of them. Don't they do things at all like Americans? Don't they walk across town to visit their mother-in-law or somebody?

Rand: Look, it is very hard to explain. It is almost impossible to convey to a free people what it is like to live in a totalitarian dictatorship. I can tell you a lot of details. I can never completely convince you, because you are free. It is in a way good that you can't even conceive of what it is like. Certainly they have friends and mothers-in-law. They try to live a human life, but you understand it is totally inhuman. Try to imagine what it is like if you are in constant terror from morning till night and at night you are waiting for the doorbell to ring, where you are afraid of anything and everybody, living in a country where human life is nothing, less than nothing, and you know it. You don't know who or when is going to do what to you because you may have friends who spy on you, where there is no law and any rights of any kind.

McDowell: You came here in 1926, I believe you said. Did you escape from Russia?

Rand: No.

McDowell: Did you have a passport?

Rand: No. Strangely enough, they gave me a passport to come out here as a visitor.

McDowell: As a visitor?

Rand: It was at a time when they relaxed their orders a little bit. Quite a few people got out. I had some relatives here and I was permitted to come here for a year. I never went back.

Discussion Questions

- How does Rand talk about the Soviet Union?

- What evidence does she give in her testimony below that the film was propagandistic in favor of the Soviet Union?

- Why do you think Ayn Rand might give this testimony knowing it could potentially hurt the people who made the film?

Context

The following excerpt comes from an internal memo produced by the American Jewish Committee on July 31, 1950, in relation to the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg treason case.

Memo Regarding Propaganda Efforts from the American Jewish Committee

Considerable concern has been expressed over public disclosures of spy activities by Jews and people with Jewish-sounding names. The present situation is regarded as being potentially more dangerous than the situation which obtained during World War II; for now the enemy is seen as Communist Russia rather than as Nazi Germany.

The main reason for concern is the belief that the non-Jewish public may generalize from these activities and impute to the Jews as a group treasonable motives and activities…

Because it seems likely that the AJC will undertake some kind of propaganda campaign in connection with these problems, I should like to make some constructive suggestions along propaganda lines…

Instead of arguing exhortatively that Jews are not Communists, that they hate Communists, that they hate Russia, that Russia hates Jews, more positive approaches based on propaganda of fact can be used…

The following propaganda of fact ideas may be tried out:

- Stories about how Russia stifles and oppresses its various minorities, including Jews, despite its claims to the contrary.

[items 2 through 4 have been omitted...]

- Stories of how Communists are fought in this country through institutional means such as labor unions (Dubinsky [David, President of the ILGWU 1932-1966] kicks them out) and through government, featuring the work of such U.S. attorneys as Irving Saypol. (In this connection it should be pointed out that Saypol and other Jews on the “right side” may have as much or as little chance of recognition as do Jews on the “wrong side.”)

- Stories and reprints of stories on Russian attacks against Israel, against Zionists, against the use of the Hebrew language.

- Reprints and stories of Israel siding with the United Nations against Korean aggression.

- Stories of how the present government in Israel keeps down Communists…

Discussion Questions

- About what does the memo suggest American Jews should be concerned?

- What does the memo suggest the American Jewish Committee (AJC) do on behalf of the American Jewish community?

- Do you think the American Jewish Committee was acting in the best interests of the American Jewish community given the circumstances of 1950?

- What might the AJC have done differently?

Context

Gerda Lerner was a writer and community organizer (and later a pioneering women’s historian) and her husband was a film editor; they lived in Hollywood during the early part of the McCarthy era.

Gerda Lerner writes about the Communist Party and the Hollywood 10

Some time late that year [1946] I joined the Communist Party. It was not, at the time, a major step or a difficult decision. Later, red-baiting and witch-hunting would make of the act of “joining” or “leaving” the CP a momentous decision with not inconsiderable consequences. The fact is that I can neither remember exactly when I joined nor where and when I first attended a branch meeting. All it meant at the time was an added number of meetings each week and the obligation to read.

What was important to me then about joining the Communist Party was that I believed I was joining a strong international movement for progress and social justice. I had no particular love for the Soviet Union, although the heroism of its people during the war had impressed me as a sign that there was indeed a vibrant experiment in social reconstruction going on in that country. After Hiroshima and Churchill’s “iron curtain” speech it seemed inevitable that sooner or later the capitalist nations would unite against the Soviet Union, as they had in the period just after the Bolshevik revolution. As it had been essential to defend democracy in Spain, so it seemed essential to defend and maintain the existence of the socialist experiment in the Soviet Union.

At present, we have all but forgotten the radical origins of democratic society in the United States. After fifty years of the cold war and internal red-baiting witch hunts, one is expected to explain why reasonable persons of good will, social conscience and patriotism could ever have worked for radical alternatives to the capitalist system. All I can say is that fifty years ago it seemed a reasonable choice to make…

The story of the Hollywood Ten has been told many times since and they have become the symbol of the blacklist. While they certainly deserve their place in history and while their defense of First Amendment rights should be celebrated, they were not typical of those victimized by the blacklist. Most of them were highly successful writers, with long Hollywood careers and some wealth and savings. On the other hand, most of the people who would fall victim to the blacklist were “little people.” The blacklisted writers could attempt to sell scripts under pseudonyms; they could write for other media, but blacklisted actors, teachers and civil servants were thrown out of their professions for good….

Fear became our daily companion. A strange car pulling up near our house, a man emerging from it, made the heart race and the knees grow weak. The subpoena servers liked to come around at mealtimes, or quite early in the morning. Each morning, you peeked out from behind window screens to see if they were there. Friends told stories, all of them bad. The FBI followed the wives of those subpoenaed; two men in regular cars would be parked near the school entrance as the wife picked up the children. They would knock at your door: two men in business suits, flashing their badges. “We’d just like to talk to you for a few minutes, ma’am,” they would say in their clipped, rehearsed voices.

“I have nothing to talk to you about” was the only answer that worked, but it would make them follow you for days, questioning your neighbors, your employer, your friends. Neighbors would avoid you; others, friendly, would warn you what was up. “You’re wanted by the FBI.”

Those were stories. The chilling effect truly worked, like slow corrosive poison. We lived in fear, we ate it; we slept in fear, with nightmares of violence and useless resistance… We had committed no crime, violated no law. We worked and paid our taxes; we cut our lawn and put the garbage out on time. We were good neighbors and by all normal standards we were good citizens. We voted regularly and in all off-year elections.

You began to wonder about yourself. Maybe you were avoiding the FBI interview because of your cowardice, your secret knowledge that, pressed hard enough, you would answer with whatever they wanted to hear: the names of friends, their version of your political life, your redefinition of yourself as having been naïve, duped, or coerced or betrayed, just so you could save your own skin, your job, your children. You hunkered down, trying to stay calm and do the daily work that needed to be done, waiting for the next blow.

Discussion Questions

- How does Lerner describe the meaning of belonging to the Communist Party?

- How does she describe her experiences during the McCarthy era?

- What kinds of choices does Lerner suggest were open to people like herself regarding cooperating or not with HUAC?

- What other choices do you think people had?

Jewish Radicalism: Why or Why Not?

Open this section in a new tab to print

Courtesy of Jewish Women's Archive, 2012.