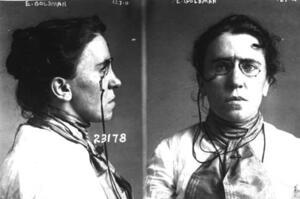

Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman was born in 1869, in Kovno, Lithuania. The antisemitism of czarist Russia propelled Goldman’s family to move to Königsberg, Prussia, and then to St. Petersburg in search of economic stability. Emma’s father was an angry, tyrannical man who didn’t believe in education for women, and after he tried to force her into marriage at age 15, Goldman immigrated to New York with her sister the following year.

Emma and her sister settled with family in Rochester, NY, and found work in the garment industry, but were disappointed to find working-class life in America not much better than in Russia. She married a fellow worker but their happiness was short-lived.

This personally discouraging early period of Goldman’s life in America coincided with a dramatic series of events in the history of American labor. On May 1, 1886, 300,000 workers throughout the country went on strike for the eight-hour workday. On May 4, a bomb was thrown into a meeting in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, where laborers had gathered peacefully to protest recent police shootings of striking workers. Then, without conclusive evidence, anarchist organizers were blamed. In a trial that was a mockery of justice, the jury found the eight defendants guilty and sentenced seven to death. This injustice sparked Goldman’s political awakening, and she began to read everything she could about anarchism.

Goldman defined anarchism as “the philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.”[1] Desiring a state of absolute freedom and believing it would never come about through gradual reform, Goldman and her comrades advocated complete destruction of the State. Yet anarchists did not champion chaos or disorder. Trusting that human nature was inherently good, they believed free people would naturally form the most productive and just systems.

Emma’s new political ideas became the focus of her life. In 1889, she left her husband and moved to New York City to join the lively culture of political meetings, labor demonstrations, and intellectual debate. Her eloquence and dedication quickly made her a popular speaker and a prominent member of New York’s immigrant anarchist community. She lectured in German and Yiddish to immigrants anxious to improve the miserable working conditions and long hours that choked their lives. She also began to lecture in English to diverse audiences including middle-class men and women, intellectuals, and even farmers attracted by her unconventional opinions and her charisma.

During this period, Goldman was linked to a general fear of anarchists as provokers of violence. This fear was based primarily on the 1892 assassination attempt on steel magnate Henry Clay Frick by Goldman’s closest comrade and lover, Alexander Berkman, and on the subsequent death of President William McKinley in 1901, shot by anarchist Leon Czolgosz, who claimed to have been inspired by Goldman. Contrary to public perception, Goldman’s primary form of political action was education, not violence. She preferred to use the spoken word to challenge the current political order. Yet she did believe that violence was at times inevitable and justified.

Goldman devoted the next decades to spreading her vision of an ideal society. She toured the United States several times a year, lending her voice to local labor and political battles, as well as speaking out on such topics as anarchism, birth control, economic freedom for women, radical education, and anti-militarism. Goldman also wrote extensively, drafting many pamphlets, penning thousands of letters to countless correspondents, and contributing articles and essays to numerous anarchist and mainstream periodicals. In 1906, Goldman founded her own political and literary magazine, Mother Earth.

Goldman’s anarchist activities placed her squarely within an immigrant Jewish culture of radical politics. She recognized, moreover, that her ideals were rooted in a longstanding Jewish tradition that emphasized the pursuit of universal justice. Yet Goldman also believed that religion was inherently repressive. She criticized what she saw as the narrow conservatism of the traditional Jewish community and did not hesitate to take part in events on Jewish holidays to emphasize her rejection of Judaism as a religion.

Throughout her career, Goldman spoke out boldly about the particular problems faced by women and demanded their economic, social, and sexual emancipation. She became a prominent figure in the struggle for free access to birth control. Goldman was also a strong advocate of free love for women and men, heterosexuals and homosexuals. She believed individuals should enter into and leave personal relationships with no constraints, and that love and sexuality were crucial to personal and professional fulfillment.

Goldman’s determination to speak out on her controversial views led to frequent arrests. The ultimate gag order on Goldman’s ideas came when the United States entered World War I, and her anti-conscription lectures and organizing were considered a threat to national security. She spent 18 months in federal prison, after which she, Berkman, and a boatload of other foreign-born radicals were deported to the Soviet Union.

In Russia, Goldman was shocked by the ruthless authoritarianism of the Bolshevik regime, its repression of anarchists, and its disregard for individual freedom. After less than two years, she and Berkman left Russia in despair.

With the exception of a brief ninety-day lecture tour in 1934, Goldman spent the remaining years of her life in exile from the United States, wandering through Sweden, Germany, France, England, Spain and Canada in a futile search for a new political “home.” In the 1920s and 1930s, while struggling economically and frustrated by the restrictions her status as an exile imposed on her political activities, Goldman engaged in a variety of literary projects. In the early 1930s, Goldman also became increasingly concerned about the rising tide of fascism and Nazism. For the next several years, she lectured frequently on the imminent dangers posted by Hitler and his fellow fascists.

When the Spanish Civil War erupted in July 1936, Goldman hurled herself into the Loyalist cause. Dismayed by Franco’s triumph in early 1939, she moved to Canada, where she worked to gain asylum for Spanish refugees and helped foreign-born radicals threatened with deportation to fascist countries.

Emma Goldman died on May 14, 1940, in Toronto. After her death, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service allowed her body to be re-admitted to the United States, where she was buried in Chicago near the Haymarket anarchists who had so inspired her.

This biography is adapted from Candace Falk’s article on Emma Goldman in Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia and from JWA’s “Women of Valor” exhibit on Emma Goldman.

[1] Emma Goldman, “Anarchism: What it Really Stands For,” in Anarchism and Other Essays (New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association, 1910), 56.