Between 1881 and 1924, two million Jews immigrated to the United States from Eastern Europe, fleeing persecution and seeking freedom and economic opportunity.[1] Some came from small, traditional shtetls, while others had already migrated to urban centers in Eastern Europe and encountered radical movements such as the Socialist Labor Bund. Many settled in New York City’s Lower East Side, where they lived in tenement housing and worked alongside other Eastern and Southern European immigrants in the area’s sweatshops and textile factories. While some immigrated with their families, many young men and women came to America on their own. They frequently sent money home to help support their families and to bring relatives over from Europe.

Though Jewish immigrants in this period faced difficult conditions in housing and work, their experiences in America were still an improvement from their lives in Eastern Europe. In America, they were able to find jobs, even if they were harsh and low-paying, and they could move freely across the country and practice Judaism openly. In Russia, the May laws of 1882 restricted where Jews could live and their right to practice their religion. Political activity and union organizing were legal in the US, and while immigrants could get in some trouble for their activism, they would not be executed or sent to labor camps. In Russia, Jewish boys and men risked being conscripted into the Tsar’s army for 25 years of service; there was no parallel in the American military.

The tenements Jewish immigrants lived in when they arrived in U.S. cities were large, crowded apartment buildings built to house the multitude of workers immigrating to the U.S. in the late 19th century. They were characterized by lack of light, air, and sanitation. Families often could not afford an entire apartment to themselves, and would take in boarders to help pay the rent. Even with this additional income, in many families, every member had to work, even the littlest children.

Sweatshops were often the first workplaces for new immigrants. Frequently operated in the tenement buildings, sweatshops were small workplaces where workers did “piece work.” This meant that workers were paid by the piece, usually doing one specific part of the garment-making process. For example, one worker might be responsible for sewing collars onto shirts, another for sleeves, and yet another for finishing a garment by sewing hems or snipping loose threads. Sometimes a whole family did “piece work” in their own tenement apartment. In other sweatshops, unrelated workers were hired by a boss, usually from the same ethnic group as the workers.

Sweatshop work was tedious and was done under difficult working conditions—poor lighting, uncomfortable chairs, stifling heat in the summer, and frigid cold in the winter. Workers were fined for such infractions as arriving late to work and for damage to their machines. In order to increase their profits, sweatshop bosses, would reduce the pay per completed piece of work, so that workers either had to work faster—and risk injury to themselves for which they would lose pay—to complete more pieces or lose part of their weekly earnings. These tactics were used in the larger factories, as well.

Some garments were produced in larger factories rather than in sweatshops. These factories might employ hundreds of workers, and the working conditions could be just as bad or worse than in the sweatshops. Workers were not to talk to one another as they worked; they could not go to the bathroom unless they were on a formal break; the noise of hundreds of sewing machines was deafening; doors and windows were locked until the bosses opened them. In both the sweatshops and the factories, workers often worked fourteen hours or more a day, six or seven days a week. There was no minimum wage, and children and women were paid less than men.

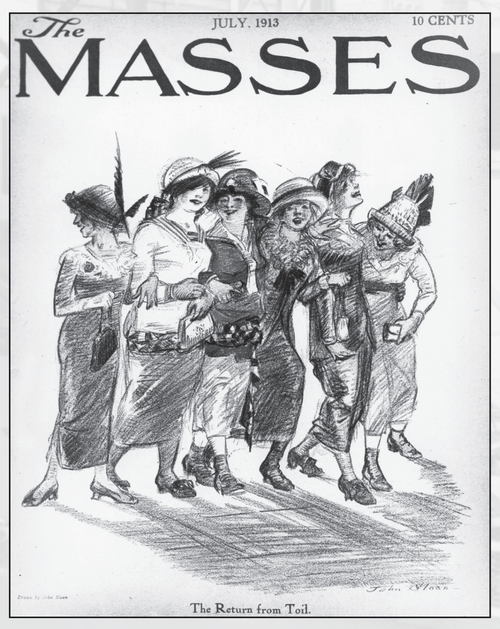

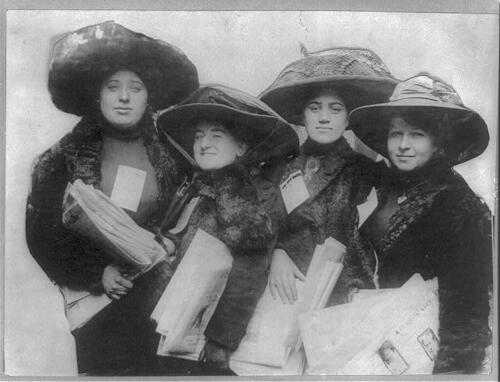

Working men had begun to organize themselves into unions of laborers in the 19th century, and by the early 20th century, there were unions of needle trade workers, such as the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), the United Cloth Hat and Cap Makers union, and the Cloak Makers Union. The unions negotiated pay rates, working hours, and safety conditions for all members with the managers of the companies for which the laborers worked. Women were generally not included in the union and so did not benefit from the collective bargaining between unions and managers on behalf of the male workers. The male union leaders mistakenly assumed that women would not be interested in the union because they would only work until marriage and therefore might not be committed to improving the workplace; they underestimated women workers’ ability to take themselves and their work seriously.

Despite the lack of support from male union leaders, women—led by Jewish immigrant workers such as Rose Schneiderman, and Clara Lemlich—were aware of the benefits and protection that unions offered and began to organize themselves. In 1907, the women who dominated a garment shop making underwear walked off the job together to protest “speedups, wage cuts, and the requirement that employees pay for their own thread.”[2] After they won relief from most of these indignities, they were allowed to join the ILGWU.

With parts of the garment industry dominated by women laborers, their entry into the unions as members and organizers was crucial for the growth and success of the unions. The unions not only addressed worker grievances; they tried to support workers in every aspect of their lives, offering educational programs in subjects such as English language, literature and politics; social and cultural programs such as dances, shows and concerts; and even opportunities to get out of the city and enjoy vacations in the country at union-run camps. In part because of the contributions and insights of women workers, the unions came to understand that they needed to address not only workers' basic needs of higher wages and safer working conditions but also the greater human needs for education, community, beauty, and dignity—a concept captured in the phrase “bread and roses.” Though the origin of the slogan is unclear, it was expressed in a 1911 poem by James Oppenheim, popularized by Jewish labor activist Rose Schneiderman in the context of a women's suffrage campaign in 1912, and was later applied to a strike of primarily women workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, that took place earlier in 1912. In the 1970s, singer-songwriter Mimi Farina set Oppenheim’s poem to music and it has since become a labor anthem recorded by many artists.