Eva Zeisel

Hungarian-American industrial designer and potter Eva Zeisel, 2001. Photograph by Daniel Wickemeyer. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Eva Zeisel was born in Budapest to a wealthy and highly educated Jewish family. After studying painting, she apprenticed herself to a potter and set up her own studio. Inspired by artistic curiosity, she moved to the Soviet Union in 1932, but the Soviets soon denounced all art forms aside from Socialist Realism, keeping Zeisel creating more practical designs. In 1936, Zeisel was arrested at the start of the Stalinist Purges and nearly executed as a political prisoner, but she eventually deported to Vienna. She then fled Austria for the United States, where her work shifted into modernism and art deco stylings. She experimented with feminine imagery and shapes within her pottery and became iconic for this style.

The playful, fluid, abstractly organic shapes of Eva Zeisel’s iconic white pottery are featured in the design collections of the MoMA and the Victoria and Albert Museum. She spent sixteen months in a Soviet prison accused of attempting to assassinate Stalin. She evolved new ceramic designs that were put into production from America to Japan, without a break, until her death at the age of 105. Along with Ray Eames, hers is only of the few female industrial designers whose name comes readily to mind.

Early Life and Education

Eva Striker Zeisel was born on November 13, 1906, in Budapest, Hungary, when it was still a twin capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Hers was a wealthy, highly educated, assimilated Jewish family. Her mother, Laura Polányi Striker, a historian, feminist, and political activist, was the first woman to earn a PhD at the University of Budapest. Her father, Alexander Striker, was a successful textile manufacturer, the first to produce rayon in Hungary.

Zeisel’s early education was in “advanced” schools where the children ran around naked and learned to dance and paint. Later, she was more formally educated by private tutors and went on to study painting for three semesters at the Hungarian Royal Academy of Fine Arts. She then put painting aside and apprenticed herself to a master potter, becoming the first woman to be enrolled in the potters’ guild. A year later, at age eighteen, she set up her own studio in a garden shed behind her parents’ house. Wearing a draw-string blouse and leather sandals, she produced folk-art style pottery, which she sold at a local market

Zeisel soon put behind any dogmatic adherence to folk art ideas and went to work in German ceramics factories, first as a hand craftsperson but rapidly rising to the rank of designer. Her work from this period is extremely competent, in the Art Deco Style.

The Soviet Union

Zeisel would not discover her own idiom until after her return from the Soviet Union, where she went in 1932. She had been impressed by vivacious dance and theater groups on tour from Russia and wanted to see “what was beyond the mountains. It was curiosity that moved me, certainly not politics” (Throwing Curves). She may have expected “the worker’s paradise” to provide limitless artistic freedom in the company of ceramic designers whose work was truly new.

Even the first years after the Revolution of 1917 had not entirely been characterized by such artistic freedom, however. In the experimental early days of the Revolution, when Modernism had freest play in graphic design, especially in posters, abstract pattern decoration in ceramics was allowed but shapes remained traditional. Then in 1932, when Zeisel arrived, Socialist Realism was abruptly declared the only legitimate artistic style. From February 1932 to late May 1936, Zeisel went from an initial administrative role, overseeing production of ceramics and glassware in Ukraine, to designing for the Lomonosov and Dulevo porcelain factories, where her work was recognized as practical and attractive. Before she had any chance of stirring up conflict by ceramic innovations, she was caught up in the whirlpool of denunciations that spread virally with the onset of the Stalinist terror.

On May 28, 1936, Zeisel was arrested on suspicion of plotting to assassinate Stalin. This was the beginning of the Purges, in which millions were executed on trumped-up charges as Stalin eliminated anyone he thought might oppose his consolidation of power. Zeisel was held and interrogated for sixteen months, ten in solitary confinement. In September 1937, she was abruptly released and deported to Vienna, thanks to personal interventions that remain a bit murky but may have involved a lover who rose in the ranks of the Soviet secret police.

Emigration to the United States

In 1938, as Hitler began to exert absolute power in Germany, Zeisel emigrated to the United States and began a hardscrabble existence. She was sculpting a plaster version of the Himalayas for a film set for fifty cents an hour when she heard of a job opening at the Pratt Institute in New York, which led in 1939 to her employment there as a teacher of ceramic design, which led to her founding of its ceramics department.

From there Zeisel found employment designing for various pottery companies and built a reputation, which crested in 1946 when she was given the first MOMA exhibition to feature a single woman designer. Her creation, the Museum dinner service for Castleton China, launched her career as a serious designer. Zeisel herself said that this set marked the transition between her “compass and ruler era” and her “lyrical” style with its “poetry of the communicative line.” (Designer for Industry, 36)

Eva married Hans Zeisel in 1937; they emigrated to the United States in 1938, and had two children, Jean in 1940 and John in 1944. Jean became an illustrator and author of children’s books; John, a sociologist. The family dynamic was stressful, with two strong-willed, brilliant parents pursuing independent careers. Hans taught at the University of Chicago law school from 1953 to 1974.

John described his parents’ relationship as “a collision of force fields” (Throwing Curves). The equilibrium of the relationship involved and perhaps required distance: Hans taught in Chicago, while New York was the center of Eva’s design activity.

Eva had no interest in Jewishness, considering it merely a religious confession. Like her parents, she regarded herself as a entirely Hungarian; when she came to America, she felt she was entirely American. She was a member of the First Unitarian Church of Brooklyn for over 70 years (author’s conversation with Jean Richards).

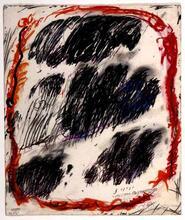

The Archetypal Feminine

One of the keys to understanding Zeisel’s work is appreciating the physical femininity of her shapes. There is nothing unusual about this. Humans like human-shaped things. We enjoy symmetrical objects, in part because we are very happy to have two eyes, two hands, and so on. Male industrial designers show a preference for phallic shapes, in everything from weapons to vehicles, a preference not entirely determined by practicality and physics. So we needn’t be shy about recognizing the feminine and body-conscious element in Zeisel’s aesthetic.

Zeisel’s postwar work is part of a movement in design called Biomorphic Modernism, which tempered geometric Bauhaus austerity with organic, irregular, wavy curves. Describing her work, Zeisel liked to use womanly and maternal terms. She likened the cream-colored rounded curves of her 1950 Norleans China porcelain dinnerware to “a baby’s bottom” (Life, Design and Beauty, 91). The wood and ceramic dining accessories she designed in 1951 for Salisbury artisans, with very rounded bowls and cruets and similarly curvy but thin and upwardly stretched candlesticks, she described as “bulging” and “waistline” (Life, Design and Beauty, 94). She called the Tomorrow’s Classic dinnerware she designed for Hallcraft in 1952 “a happy family of shapes” (Life, Design and Beauty, 98).

Red Wing Pottery salt and pepper shakers from "Town and Country" dinner service. Glazed earthenware, ca. 1947, by designer Eva Zeisel. Via Wikimedia Commons.

In 1947 Zeisel followed the critical success of the Museum line with a popular one, the Town and Country set of inexpensive “luncheon ware” produced by Red Wing Potteries in Minnesota, in an informal style that appealed to younger, post-war consumers and that would feel “as Greenwich Village-y as possible.”(LDB p. 76) Unlike the museum line, this set was solid, durable, and brightly colored, in playful bulbous shapes. Among the pieces were the iconic salt and pepper shakers that may have inspired the “schmoo” character that appeared in Al Capp’s Li’l Abner comics a year later. One might fairly see in these forms an abstracted, modern “Madonna and child.” Zeisel herself said the “schmoos” illustrated her feelings for her daughter (Designer for Industry, 93).

The Royal Stafford One-O-One set was named for Zeisel’s 101st birthday in 2007, the year it debuted at Bloomingdales. Zeisel’s unconscious visual invocation of the divine feminine nearly breaks through to conscious awareness in this series’ iconic “Rockland Bowl” (named after Zeisel’s home in Rockland, New York). The stylized uterine cavity and upswept fallopian horns of this bowl, which could really only accommodate fruit or rolls as a serving piece, is audaciously explicit in its celebration of the feminine.

Recognition and Legacy

Zeisel’s works are in the permanent collections of major museums worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, The Cooper-Hewitt Design Museum, the British Museum, and The Victoria and Albert Museum. Her iconic works have been steadily reissued, currently by Klein Reid, Neue Galerie, and Eva Zeisel Originals. Her vintage work is popular on Ebay, and the Eva Zeisel Forum on Facebook has nearly a thousand members.

Eidelberg, Martin. Eva Zeisel, Designer for Industry. Exhibition Catalogue, Le Château Dufresne, Inc., Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Montréal, 1984.

Faintly, Mildred. Conversation with Jean Richards, October 30, 2024, Rockland, NY.

Johnstone, Jyll, dir. Throwing Curves: Eva Zeisel. Canobie Films, 2002.

Kirkham, Pat, editor. Eva Zeisel, Life Design and Beauty. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2013.

Young, Lucie. Eva Zeisel. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2003.

Ziegerman, Gerald. Eva Zeisel, The Shape of Life. Erie, PA: Erie Art Museum, 2009.

Zeisel, Eva. On Design, The Magic Language of Things. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 2004.

Zeisel, Eva. “The Playful Search For Beauty.” TED Talk, February 2001. https://www.ted.com/talks/eva_zeisel_the_playful_search_for_beauty?subtitle=en

Zeisel, Eva. A Soviet Prison Memoir. Wrocław, Poland: Brent Brolin, 2014.