Artists: Israeli, 1970 to 2000

During the 1970s, Israeli art was divorced from feminism, and female artists were often forced to ignore their identities as women while creating art. Because Israel thought of itself as a state of equality in which gender did not prohibit employment, it was not necessary to represent feminism in art. However, the roles women played in the arts sector began to come into question, and in the 1980s and the 1990s, Israeli women became more prominent artists as well as curators, writers, and educators. Ethiopian and former Soviet immigration to Israel in the 1980s also brought issues of race and ethnicity into Israeli art, continuing through the 1990s and culminating in the 2000s with art that centered gender and ethnic identity.

The 1970s

The 1970s were a conceptual and political period in Israeli art. The dominant approaches in art during these years articulated modernism among national and social concerns and struggles. It was a shaky decade: the euphoria brought by the 1967 war gave way to revived territorial and theological disputes; the emergence of the "Black-Panthers" protests that claimed equality for Mizrahi citizens and combatted discrimination against them; Palestinian terror attacks in Israel and abroad; the trauma of the Yom Kippur war; and finally the 1977 election of the right-wing Likud leader Menachem Begin, which ended almost 30 years of Labor Party rule.

The 1970s saw women attain increasing appreciation and presence in the art world. Women artists active during previous decades, such as Lea Nikel (1918-2005), Aviva Uri (1922-1989), Siona Shimshi (1939-2018), Tova Berlinski (1915-2022), Hava Mehutan (1925-2021), Ruth Schloss (1922-2013), Alima (Rita Alima) (1932-2013), Nora and Naomi) Nora Kochavi [1934-1999] and Naomi Bitter [b. 1936], Hannah Levy (1914-2006), Rahel Shavit Bentwich (1929-2022), and others held important solo exhibitions.

Unlike their colleagues in the United States and Europe, however, only a few of the women artists who participated in the Israeli art world were recognized as feminist artists, although in fact they were, and what they did was feminist art. The most prominent was Miriam Sharon (b. 1944). Her means of expression, and those of the women whose works she curated, were patiently hand-crafted works in the tradition of earlier women artists and projects that aspired to draw the public closer to feminism, ecological ideas, and art. These works resolutely conveyed a feminist message about the suppression of women in society.

During this period, the art establishment tended to reject this model of feminist art as tendentious and considered feminism and gender identity to be irrelevant in the arts and to Israel’s supposed state of gender equality. The mostly male “gatekeepers” of the art field (curators, teachers, and critics), such as the painter Raffi Lavie, generally opposed narratives, figurativity, and identity discourse in the visual arts, considering them part of a “reactionary” wave. This perception had especially negative effects on interpretations of the works of women artists, even those, like Michal Na’aman (b. 1951), Deganit Berest (b. 1949), Efrat Natan (b. 1947), and Tamar Getter (b. 1953), who gained visibility and prestige under Lavie’s patronage. And it was not only men who espoused this attitude. In the late 1970s, Sarah Breitberg-Semmel (b. 1947), one of the most prominent curators in the Israeli art world, wrote: “There is Israeli art and there are women artists, but the combination of the two has no practical meaning" (Breitberg-Semel, 50). Consequently, young women artists operated in an aggressive male arena that compelled them to dismiss their female identities, including the possibility of being simultaneously good artist and mothers (Scheflan-Katzav). Because hegemonic artistic discourse excluded feminist discourse and, more generally, the very mention of women and women-artists, women artists who engaged explicitly with themes of sexual identity, diversity of gender identities, or androgynous identities felt coerced to maintain a consensus of denial.

Nevertheless, Performance and Body Art began initial steps in Israel. Yocheved Weinfeld (b. 1947) and Efrat Natan expressed a feminine bodily “self” in performances and in Body Art. In photography and performances, Weinfeld made use of images of childbirth and religious rituals and engaged with questions of identity and feminine sensitivities. She influenced other young women artists, who took up the conflicts she emphasized in her works and the means she employed. Natan, too, put on performances in which she used herself and her own body to express feminist, social, and political criticism. Bianca Eshel-Gershuni (1932-2020) created unusual items of jewelry in which she combined noble and cheap materials, producing a deliberate magnificent kitsch. Doing so, she created a “counter feministic kitsch,” since kitsch was usually identified as a synonym of a feminine lack of high artistic taste. Despite the fact that Sara Breitberg curated Eshel-Gershuni’s solo-person exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum in 1985, Eshel-Gershuni's artistic repertoire that displayed pseudo "ritual" altars, textural pictures, and "imperfect" jewelry remained out of the Israeli canon at that time but gained recognition three decades later. Her artistic creation opposed established paradigms of sophisticated, conceptual, minimalistic tendencies that Breitberg described in 1986 as "The Want of Matter: A Quality in Israeli Art."

The 1980s

The 1980s brought deep changes in Israeli society. For the first time, a Women’s Party participated successfully in elections for the Knesset, represented by Marcia Freedman. The elections for the Tenth Knesset (June 30, 1981) came at the end of the most turbulent campaign to date in Israel’s history, saturated with ethnic tensions and violent incidents. New political forces emerged, such as Tami (associated with the Masorti or Conservative movement), led by Aharon Abu Hatzera and Vicki Shiran, who played a key role in the Mizrahi feminist movement. The First Lebanon War (1982) and the first Intifada in the mid-1980s were watersheds for Israel’s Jewish and Arab populations. Waves of Jewish immigration from the former Soviet Union and from Ethiopia changed the country’s demographic texture and raised new issues of identity.

In view of this sociopolitical reality and the concomitant economic privatization and disintegration of cultural hegemonic myths, Israeli identity broke into complex and hyphenated identities—including an incipient gender discourse—that sometimes clashed and sometimes accommodated each other. This situation served as a backdrop to artistic trends that focused on biographical elements and personal modes of expression that raised questions about women's roles in the private and public spheres as artists, objects, and political agents.

In this environment, a younger generation of women artists founded collective noncommercial galleries and challenged the art world’s infrastructure. Batia Grossbard (1910–1995) painted in a style with an affinity to American Abstract Expressionism, juxtaposing smooth color planes with aggressive brush splashes and creating huge diptychs. Lea Nikel continued developing her rich abstract work, and Liliane Klapisch’s (b. 1933) painting evolved from an abstract style characteristic of France in the 1950s to a more classical style characterized by observation of nature in the 1980s. With candor and directness, Nora Frenkel (1931–1995) exposed her existential anxiety and dread as influenced by her terminal illness, painting hundreds of self-portraits documenting her face’s loss of beauty and disintegration.

Ofra Zimbalista (1939-2014) dealt with the theme of death and extinction of the spirit in the body, in sculptures made from body molds of her acquaintances. She erected installations and sculptures of groups of people in transitional situations, hanging and climbing, seeking their place and their serenity, in many public places in Israel. Nora and Naomi combined tradition with contemporary symbolism in their large-scale sculptures. Siona Shimshi pioneered the inclusion of ceramic work as a genre of equal value to other means of plastic expression.

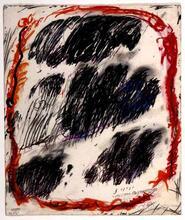

The young generation of women artists in the 1980s was involved in transitions in painting, sculpture, photography, performance, and video-art. Pamela Levi (1949-2004) represented the “Return to Painting”—a traditionally masculine genre—in work that was deliberately rigid and lacking in grace; her pictures, based on photos, displayed the violence of Israeli public space. After the Lebanon War, she felt a need to express the human condition by means of the human figure, which had virtually disappeared from Israeli painting. The younger Eti Jacobi (b. 1961), who also joined this “Return,” painted with ease, attractiveness, and a certain degree of alienation. The large brushstrokes and decisive forms in the paintings of Yehudit Levin (b. 1949) challenged male dominance in the abstract movement. Feminist theory has shown that there is a connection between the role of male painters in abstract expressionism and the broad and all-embracing pictorial gestures. Levin proposed something similar but different in the pictorial qualities that can be seen as non-binary. The broad paint smears of Smadar Eliasaf (b.1952) were also linked to the heroic tradition of the expressive abstract, and, as with Yehudit Levin’s works, only a second viewing revealed how delicate they were.

The sculptures of Sigal Primor (b. 1961) and Drora Dominey (b. 1950), in metal and heavy wood and rigid geometrical forms, combined stylistic rigor with feminine issues. In Primor’s work, the feminine content was concealed in codified forms. Masculine momentum and feminine introversion existed side-by-side in her works as complementary qualities. A sex–death tension entered Dominey’s works through motifs of division and parting between masculine and feminine representations. Penny Yassour (b. 1950) designed condensed sculptural elements that recalled architectonic bodies, or mazes positioned on the ground to create a kind of industrial space that she described as mental maps. A more modernist sculpture approach appeared in the basalt stone artworks of Dalia Meiri (b. 1951) and the aluminum and stainless steel works of Tamara Rikman (b. 1943), which were similarly connected to a stereotype of masculinity. Meiri’s sculptures were located between the archaic and the technologically sophisticated, between the cultural and the pre-cultural. In the memorial sites she erected, Meiri emphasized the theme of devotion and sacrifice for land and place. Rikman’s sculptures were based on Minimalist aesthetics, defined forms, and industrial materials.

The female-artistic voice that made itself heard in these years expressed a social criticism stemming from a much more emotional source than had hitherto been expressed in Israeli art, but still without any specifically feminine aspects, in particular among the older generation. Aviva Uri employed visual signs of holocaust, disintegration, explosion, void, and death. Her “Requiem” designated a transition from a world in which the pure spiritual was present to a reality dominated by darkness and mourning, an atomic or ecological holocaust. Mina Sisselman responded to the revolutions in eastern Europe, the ecological dangers threatening the globe, and the Lebanon War. Siona Shimshi created series of large figures that bluntly conveyed social messages. Hava Mehutan, pained by the socio-political situation, materialism and acquisitiveness, the Lebanon War, and the futility of wars in general, created conceptual environmental works whose disintegration and reintegration into nature were a part of her protest.

During this period, Nora and Naomi’s engagement with sources, nature, and the local soil also touched on traumatic events experienced by the entire nation and offered a fresh point of view about Zionism and Judaism. Dorrit Ruth Yaacoby (1952-2015) worked in a different way but one that was also connected to the dedication and patience of a woman “doing craft.” Her works were at times built over several years, layer upon layer, and incorporated fragmented objects. Through the figure of woman, she expressed her freedom and ability to fly or to risk falling, to attain new experiences of redemption in a new firmament, to free herself of impurity. The soul’s self-extrication from the material that surrounds it (the body) facilitates coming closer to God.

The first performances of Tamar Raban (b. 1955) contained distinct local-political content. She played a major role in the emerging performance field in Israel, founding the Dan Zackheim 209 Shelter for Interdisciplinary Art in the late 1980s, the Performance Stage, and Ensemble 209, and passing along her knowledge and experience to new performance artists.

Joyce Schmidt believed in the purity of paper created from the fibers of local plants and made paper a moral subject and object. Mirit Cohen expressed deep pain and a cry for help in a series of drawings titled “Mind Script” that displayed several body incisions in a very expressive way.

Like Efrat Nathan and Drora Dominey, Idit Levavi-Gabbai (b.1953) was born on kibbutz, a community that defined itself as egalitarian and utopian but succeeded in dealing entirely with neither gender nor the emotional welfare of children who grew up without intimacy and without warm parenthood. Gabbai dealt with kibbutz themes and the role of halutzot (women pioneers) through personal conceptual painting, later achieving a kind of closure in the group exhibition "Lina Meshutefet" ('Togetherness' The 'Group' and The Kibbutz in Collective Israeli Consciousness), curated by Tali Tamir at the Tel Aviv Museum in 2006.

In the 1980s, a number of women artists established formal “feminine” frameworks, such as the canvas as a piece of embroidery or stitching in the works of Naomi Simantov (b. 1952), Nurit David (b. 1952), and Jenifer Bar-Lev (b. 1948), whose creations also incorporated interaction between text and textile. The works of Miri Nishri (b.1950) were characterized by a strong sense of corporeality and sensuality through the use of physical materials and textures such as coffee, among other materials, as paint. The collage strategy of her entire oeuvre—including video-art pieces, endlessly moving from one subject, identity, or genre to another—expresses her "in between" identity as a young immigrant girl. Since her ongoing project "Is the baby yours" began in the 1990s, she has continued to explore questions of belonging and parenthood. Like Levavi-Gabbai, her approach is a combination of conceptual (in her case "mail art") with pictorial and manufacture art.

Tamar Getter, Deganit Berest, and Michal Na’aman set up feminine models as subjects of reference and models for identification and dealt with women and gender issues, but they did not identify explicitly as feminist artists. Michal Heiman enlarged newspaper photographs of both famous and anonymous women, adding captions about them and presenting a very different approach not only from what male photographers exhibited but also from women artists such as Michal Na’aman, Diti Almog (b. 1960), Sigal Primor, and Eti Jacobi, who dealt with a feminine presence in their works, from which the signified—the woman—was absent. Michal Na’aman explored the question of sexual identity by creating androgynous creatures that challenge stereotypes of both femininity and masculinity. She also dealt with connections between blindness and castration and between text and visual image.

During the 1980s, art institutions supported and encouraged emerging women artists such as Michal Neeman and Tamar Getter, who represented Israel at the Venice Biennale in 1982. But the local consensus was still “there is no women's art.” As Ellen Ginton noted in 1990 in the catalog of "The Feminine Presence" exhibition, during her term as curator of the Tel Aviv Museum, "the artists themselves are totally silent about the feminine element, and actually deny its existence.… It may very well be that those women artists who refused to renounce the notion of ‘women's art’ were rejected” (Ginton, 1990). Female voices were not only silenced but the feminist propositions of others, such as Bracha L. Ettinger, Miri Nishri, and Dorit Feldman (1956-2020), were interpreted within a very narrow formalist context and were sometimes distorted or even misconstrued. The same fate befell the oeuvres of Pamela Levi and Jennifer Bar Lev, who were raised in the United States and studied art during the second wave of feminism there. Having no counterparts in Israel, their feminist art could not be understood, contextualized, and appreciated properly in its time; only belatedly was it received as feminist women’s art (Dekel). In this climate, the few Mizrahi women who studied art, such as Shuli Nachshon (b. 1951, Morocco) and Shula Keshet (b. 1959), were not encouraged to explore and express their whole identity; neither were women who had embarked on religious journeys, such as Nechama Golan (b. 1947).

Women artists engaged in research and critical writing as part of their artistic practice. Bracha L. Ettinger’s theoretical writing was connected with her painting and reexamined the description of female mechanisms and structures—structures perceived by Freud and Lacan as derivatives of masculine sexuality. Other women artists, including Tamar Getter, Nurit David, and Naomi Simantov, wrote important essays for catalogs and periodicals.

Intellectual, scientific, and research-oriented approaches characterized the works of Deganit Berest, Tamar Getter, Michal Heiman, and Dorit Feldman. Berest’s paintings, influenced by mathematical and physical theories, attested to her belief in the connection between science, art, and philosophy. Heiman, turning the viewer into the patient being diagnosed, dealt with the point of contact between psychology and the museum and with the essence of the image and of identity. Getter investigated the possibility of a constructive representation of an irrational world of images and created classical contexts by juxtaposing charged Israeli motifs with quotations from Renaissance masters. Feldman incorporated various fields such as anatomy, physics, geology, and archaeology, which in her view work together in harmony in art as in nature. Ettinger’s works involved intensive research and expertise in psychoanalysis, feminism, history, language, and the process of image formation.

The end of the 1980s was marked by two exhibitions. The “Feminine Presence,” curated by Ellen Ginton at the Tel Aviv Museum in 1990, marked the beginning of an open and wide-ranging female and feminine discourse in Israeli art. Seventy-one women artists who had never defined their work as “feminine” participated. The second, "Meta-Sex-94," curated by Tami Katz-Freiman at the Ein Harod Museum in 1994, reflected a new approach toward sex, gender, and sexuality through multiple media. The fifteen participating artists presented images of body parts, sexual implements, personal articles, domestic objects, hygiene-related items, eating and secretion, kitchenware, motherhood, women-soldiers, brides, feeding instruments, biological mutations, and consumption products. These works challenged accepted relationships of woman-mother, woman-nature, woman-home, woman-dirt, and woman-man, undermining feminine conventions.

However, at this time, most women art critics still did not welcome the possibility of gender-based art or consequently of female art exhibitions. In the veteran newspapers Maariv, Davar, and HaMishmar, critics such us Rachel Angel, Dorit Keidar, and Talia Rapaport completely rejected the legitimacy of gender interpretation, an interpretation that would have required them to examine their own positions as women art critics. The common denominator in their writing was to see female presence per se as a sign of symbolic gender equality in the field, as Angel argued: "The emphasis should be not on femininity but on personality." Moreover, "the glass ceiling " persisted, maintained in part by a large number of older women artists who continued to create, such as Lea Nikel, Liliane Klapisch, Batia Grossbard, Mina Sisselman, Hannah Levy, Siona Shimshi, and others; they saw themselves as artists equals to anyone but rejected gender perspectives on their work or the gender-based dynamic in the art field.

The 1990s

In the 1990s women’s art became more explicitly established in Israel, and both art critics and academics addressed the validity of a feminist approach. Discourse about gender and feminism gained increasing reception among the younger generation. Interdisciplinary gender studies programs were established, including courses about women artists and women’s history. The growing number of successful women artists demonstrated that the dominant discourse had become more inclusive of the female presence in local art.

During this decade, several group exhibitions of women artists in Israel dealt in depth with various aspects of female life experiences. The 1990s art scene was explicitly postmodern and open to international exchange and a number of women artists attained international success, with some working in Europe or the United States. These included Michal Rovner, Diti Almog, Sigal Primor, Bracha L. Ettinger, Yehudit Sasportas, and Sigalit Landau. Women artists worked with an awareness of the format of the painting as a work surface that allowed for the creation of feminist works and as a platform for the presentation of their artistic statements about their identities as artists and as women.

These women artists grappled with social molds; with female characteristics; with women’s bodies as material, as sex objects, and as a field of action; with women’s place in society, their struggles for identity, and their battle against firmly rooted images, dictates, and stereotypes. Yehudit Levin, who had formerly presented narrative figurative images in which the figures’ gender was indistinct, began in the 1990s to paint distinctively female figures. The princess-like figures in their red dresses burst out from the canvas and the transitions between transparency and opacity hinted at their various limbs and organs. Michal Na’aman painted with a rich and many-layered materiality, sophisticated verbal puns, intellectual riddles, and intentional interchanges between masculine and feminine. Diti Almog’s paintings stressed seductiveness and sensual charm. She proposed an analogy between woman and the work of art, both eluding male attempts to comprehend their nature and value.

Hilla Lulu Lin (b. 1964) presented her own world of fantasies and nightmares, from a feminine point of view, in ritualistic, theatrical acts entailing injuries to her bared body and sensual poems in a font and with rules that she developed for her own style. Miriam Cabessa (b. 1966) imprinted her body on the surface of the work or urinated like a man; the traces of the act were the painting, in a parody of the female models men had created throughout history. Tova Lotan (b. 1952) and Tamara Messel used photography to focus on the female body, sexual identity, and various manifestations of femininity and its implications—beauty, seduction, the surface and what lies beneath it. Osnat Rabinovitch used “masculine” work tools like a carpenter; her delicate pieces of furniture looked stable and enclosed large spaces but were in fact fragile. Michal Shamir’s (b. 1957) choice of simple and perishable materials constituted something of a feminine remonstration against the massive iron constructions that had become imprinted on the Israeli mind as “correct” masculine sculpture. She created a gender tension by incorporating objects considered to be “feminine” and sentences with sexist concepts in an ironic way of confrontation by a deliberately "wrong" combination of objects, materials, and words. Marilou Levin (b. 1967) treated femininity as an intimate subject, not as a manifesto. She expressed the disparities between femininity as an almost heroic concept and the everyday reality of female existence and presented woman as rebel, aware of feminist revolt but in conflict with the obedience and submissiveness of the well-brought-up good girl. Yehudit Sasportas (b. 1968) employed smooth carpentry to create sculptural works that were hybrids of objects created from the domestic environment but with their functionality neutralized, undermining the picture of the home and of a normal world and telling of a personal and a cultural loss.

The women artists who constituted the next generation of artists working in pottery—including sculptor Varda Yatom and Lidia Zavadsky, with her large pots that were actually very powerful sculptures—reminded the public that pottery was originally a masculine craft requiring physical strength and high technical skill. They saw a challenge in giving new content to this charged, cultural, and firmly established ancient language.

The roles of women artists, curators, writers, and art teachers became more diverse in accordance with the dominant multi-cultural and interdisciplinary narratives in the cultural realm. Women curators proliferated in the galleries and museums of the periphery, including Galia Bar-Or (b. 1951) at the Ein-Harod Museum, Dalia Levin (b. 1947) at the Herzliya Museum, Daniella Talmor (b. 1948) at the Haifa Museum, Tali Tamir (b. 1954) at the Hakibutz Gallery, Ariella Azuolay (b. 1962) and Ilana Tenenbaum (b. 1955) at the Bograshov Gallery, Miriam Tovia (1932-2020) at the Hakibutz Gallery (1978-1979) and Ramat Gan Museum (1985-1987), and Drorit Gur Arie (b. 1955) in Petah Tikva. These women brought forward narratives that had been largely ignored.

To a large extent, feminist theories became integrated into Israeli art and culture, making possible a more emotional and biographical art, connected to everyday life. Many engaged in self-expression, even in confession: exposures of childhood, relations between parents and children, anxieties connected with motherhood. Some women artists formulated representations of female identity by means of contemporary realistic painting, incorporating direct or indirect statements of their individual views of reality and of their identity as women in Israel.

In some cases, feminist approaches combined personal and autobiographical matters that also served as points of departure for political statements. In the 1990s the socially and politically involved emotional-female voice found expression in a clear and assertive femininity following the concept that “the personal is political.” Mirjam Bruck-Cohen(b. Switzerland 1943), for example, embroidered images of Palestinian towns and villages and of her experience as a refugee from World War II. Meira Shemesh (1962-1996), too, made use of autobiographical materials. She created a tribute to the women who had preceded her, who had decorated her life with cheap objects of artificial beauty. Her sensitive, avowedly feminine works and her concepts of ornate beauty were an expression of the Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi culture with which she had grown up. At the same time she "winks" at the art world and the political discourse as it was present even in the name of her exhibition ironically titled "An Iraqi Expressionism," expressing both social and self-criticism.

Employing realism and classical techniques, Haya Graetz-Ran (b. 1948) expressed myths of sacrifice and the need to suffer in order to give meaning to life, an inseparable part of the values on which she and other girls born at the time of the establishment of the State of Israel had been educated. Ofra Zimbalista’s hard feelings as a mother and a woman in a society that does not save its children from wars triggered many of her works. Tamar Raban created personal-autobiographical performances that reflected feminist and political influences. In Sigalit Landau’s works, the weak and the “other” became parts of her “self.” In terms of the Israeli reality, she was a Palestinian; in the gender reality she was a woman; in the social reality she was the foreign worker, the immigrant, the homeless. Yehudit Matzkel (1951-2013), who experienced parting from her son who was drafted into the army as a painful division between “female” and “male" gender categories, dealt with the symbiotic connection between a mother and her son, the pre-Oedipal state in which the two of them are a single entity. Adina Bar-On (b. 1951) expressed the abstraction of the word by means of her body. Varda Yatom’s sculptures in ceramic materials were concrete symbols of human anxieties in a painful reality. She engaged in wandering journeys and the eternal quest for both personal and collective identity, from its cultural and ethical sources, via Israeli and Canaanite identity and concluding with the universal-Jewish identity.

A different approach was developed by Shlomit Bauman (b. 1962), who deals with research aspects of the field of ceramic design, drawing inspiration from cultural questions, technology, tradition, and design. Bauman examines ceramics' methods in a broad context of material culture. Her work combines art, research, curation, and education to understand matter and material culture as a way of life. Over the years, she initiated projects and exhibitions to promote a complex discussion within the ceramics field itself and the craft and design as well art fields.

Since the beginning of her artist career, Ariane Littman-Cohen (b. 1962 Switzerland; immigrated 1980) has questioned the contrasting image of the “Holy Land” and the reality of an up-and-coming, conflict-laden state. In 1998, through her installation “Eden Water,” Littman-Cohen used the biblical connotation as an ironic marketing strategy. “Holy Water,” ‘Holy Earth,” “Olive Oil,” and “Holy Incense” from the “Holy Land” packed in tiny bottles are among the souvenirs pilgrims and tourists find in shops selling devotional objects in Jerusalem’s Old City. From the 1990s to today, Littman has dealt with maps, which expose shredded, erased, stitched, and frequently changing sections of the conflicted land Israel-Palestine. Made of scraps of rough paper, censored, covered with colorful stitches she embroidered with her own hands, they have a similar structure to the territory. Littman-Cohen’s maps do not serve any utilitarian function. She wants to show that it is possible to deal with the "territorial question" through a female point of view and through essentially female rituals when she dresses and embroiders her wounded maps. Littman-Cohen chooses to cover the country's map with embroidered stitches; doing so, she performs female craft as well a caring ethical role far from the typical male manner of dealing with the theme in Israeli art. The act of dressing as a performative-cathartic act of healing is also evident in a series of works in which Littman-Cohen dressed monuments or olive trees and photographed them on video. She challenges the field the material, the gender and the political discourse.

Jenifer Bar-Lev’s canvases contained text and ornaments incorporated by means of demanding stitch work and dealt with stories connected to the female world of sewing, to her own personal world, and to the world of art and artists. A clean geometrical aesthetics repeatedly emphasized feminist messages. The meticulous coloring in the oil paintings of Tal Matzliah (b. 1961) was reminiscent of folkloristic handicrafts that involve patience, unglamorous work, and total dedication. In this discipline she expressed hard and forthright messages of struggle for survival against obsessions with sex and eating, which could at last be discussed with a sense of freedom. Naomi Simantov offered meticulous, industrious painting that imitated weave patterns. In a manner similar to the act of weaving, she painted ornamental patterns of carpets with a fine brush. Talia Tokatly (b. 1941) gave voice to girls and young women by developing a ceramic process that incorporated embroidery with the Hebrew words for “vessel” and “voice” as charged words in the discourse on femininity. In the works of Meira Shemesh, a distinctive feminine expression was evident in the slow, patient, and precise material touch, the artist demanding of herself a strict regime of work with vulnerable and brittle materials

Women artists of the 1990s transformed the status of women’s handicrafts—such as sewing, embroidery, weaving, colorful ornamentation and even kitsch—raising them to equality in the hierarchy of canonical artistic materials and means of expression, while proposing their own distinctive, feminine, and postmodern approaches to the genre. Bianca Eshel-Gershuni’s consistent, sophisticated, and manipulative use of materials identified as feminine kitsch was considered a daring breakthrough and a model for younger women artists in whose works her influence is discernible.

The 1990s also brought a change in higher education: more academic programs in Fine Art and Design opened, as well as the first Graduate Fine Art program at Bezalel Academy. Etti Abergel (b. 1960) studied at Bezalel and developed her sculptures and installations based on found materials, creating complex imagery fluctuating between physical and abstract objects. Abergel’s works reclaimed both the sources of sculpture modernism and her own cultural and biographical sources. Her works attracted interest from international curators such as Francesco Bonami, who invited her to participle in the 50th Venice Biennale. In her installations, Abergel usually leaves everything life-size, piled; as critic Gilad Meltzer argued (Haaretz, April, 22, 2022, Galleria section, 4), "[S]he chooses not to choose. Quantities, not samples. Countless pencils, measuring tapes, brushes, nets, baskets and boxes, bicycles and ladder." Wandering is also a central practice in Abergel's life and art, connected with the theme of immigration and migration between cultures and sites as both a metaphor and a concrete material reality. Mixing Eastern feminist aesthetics and Western aesthetics, based on the modern grid model as a psychological infrastructure, she keeps chaos on the verge of collapse. Her work also engages "Mizrahi Masortiut," challenges the meaning of transgression in Israeli society, and disentangles usual boundaries between secular and sacred realms in general and in arts in particular. The re-identification of Mizrahi women artists as Masorti (traditionalist) as the convergence of a hybrid identity with critical anti-hegemonic and postmodern voices in the Israeli public space promoted a critical post-secular discourse.

Although the avant-garde galleries of the 1980s in Tel Aviv's run-down downtown, which attempted to recreate New York City’s East Village, had begun to close, two galleries in the early 1990s solidly and modestly challenged gender discourse: Gallery Studio Borochov and Bugrashov Gallery. There Ilana Tenenbaum began her curatorial career. Galleries also emerged in the A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim. First in Kabri in 1977 and then in the 1980s and 1990s from the south to the north, more and more women took on curatorial roles in these venues, which had in the past mostly served as productive sources.

These grassroots developments changed the balance between the hegemonic male center in the art field and the new women’s voices. Young women artists like Meirav Shin-Alon (b. 1965) and Ruthi Helbitz Cohen( b. 1969) exhibited their first solo shows in the Borochov Gallery.

Meirav Shin-Alon's art creations explore the connection between the physical and narrative dimension and raise questions concerning issues of identity, gender, and trauma through drawing on paper and site-specific installations. From her first exhibitions, her intimate work evokes the concept "the personal is political," as she explicitly declared: "My aim is to touch on the ‘silenced’…. On the whole it is possible to trace two axes that feed off one another simultaneously in my art. The first is a material, visual, sensual and emotional layer that raises formalist questions, the second layer is conceptual, critical and strives to raise questions about the artistic discourse and the art world" (Shin-Alon). Since the 1990s, her works has engaged with body images in different supports and materials: painting, drawing, installation, artist-books. In some works, it seems that the surface of the canvas, the paper, or the wall represents the surface of the body or even the relationship between the inner hidden world and the outside world. The trauma breaks through the skin/surface and creates a state of external bleeding.

Body and trauma occupy a central role in Helbitz-Cohen’s work, too. The female body is the key to understanding her work. Dutch curator Beatrice von Bormann described Helbitz-Cohen’s work as a sort of re-construction performance in order to deal with trauma, loss of innocence, and male violence playing different roles: a clown, witch, child, or femme fatale; as a mythological goddess or historical figure; hanging from the ceiling, floating, lying down; fragmented in space, alone or in the company of other complementary figures. Von Borman emphasizes that Helbitz-Cohen’s women created contested images by pulling their bodies apart, by painting heads, limbs, or organs separately and then putting them back together like a mismatched puzzle, in which the individual pieces don’t quite fit. Beyond the horror, disgust, and pain lies a world of delicate beauty.

Women artists’ choice of figurative representation ran the risk of recycling the discriminatory images that created a seductive object for the masculine gaze. However, these artists subverted the analogy and offered art that was not merely an object. They employed humor, mostly of a grotesque kind, and self-reflexive irony; discussed the “other,” the stranger; and created a visual art that speaks about the need for sensuality, touch, and aesthetic pleasure. They dare to hold together beauty and horror.

In 1998, Khen Shish (b. 1970), who spent some years in Europe after her graduation from Oranim College, returned to Israel and completed an MFA at the Bezalel Academy, in addition to graduating from the New Seminar for Visual Culture, Criticism, and Theory, Camera Obscura. Shish works in a wide range of techniques. Her oeuvre includes paintings, drawings, collage, works executed on television screens, large-scale wall paintings, and installations. Her works deal with identity and alterity and introduce expressive sites oscillating between chaos and horror, nature and culture, refinement and excess, frugal and Baroque.

The 1990s saw a widening of the scope of advanced art studies in Israel and abroad, and women artists engaged in graduate studies in Europe and the United States. Contact between women and feminist artists was more intensive and intimate than in the previous generation. Dafna Shalom (b. 1970) studied at the International Center for Photography in New York and graduated from Hunter College of Art. Her videos and photos are displayed in private and public collections worldwide. Shalom’s works, which are both conceptual and emotional, raise questions about otherness, corporal fragility, and identity. Shalom was deeply familiar with traditional Jewish ritual and the Arabic language and dialects; while studying art in New York, she began to fuse gender, ethnicity, and ritual. In her series of video-arts that dealt with prayers and blessings, she proposed a return to the somatic. With the woman’s voice and her “talking” hands in the background, one could not but see in this lyrical work a challenge to the exclusion of the body, and of woman’s body, from the traditional rite and unquestionably a protest against the banning of her voice. By shifting the weight of the read or recited text—symbols and books (identified with males)—onto nonverbal language (sign language, woman’s singing, visual language), an additional interpretive stratum was evoked. Engaging the body, Shalom raised questions of race and racism dealing with “gender blindness” in Judaism as well as with "Mizrahi blindness" in Israeli art and society.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, ethnic identity and gender identity demanded the right to be represented in the discourse and field of art, after years of discrimination, racism, social exclusion, and the struggle for economic resources. Furthermore, the intersection between gender and ethnic reclaiming promoted exhibitions of Mizrahi women artists and the emergence of Mizrahi feminist organizations such as Ahoti. The first art exhibition under this emblematic name was held in Antea, a multi-cultural feminist art gallery in Jerusalem of the organization Kol haisha (The Woman’s Voice). While the 1990s opened with "The Feminine Presence," as a sort of summary of developments in the 1970s and 1980s, the decade's closing challenged the previous waves of Israeli feminism by celebrating a complex spectrum of identities, such as those represented in the exhibition "Sister (Ahoti): Mizrahi Women Artists in Israel,” curated in the Jerusalem Artist House by Shula Keshet and Rita Mendes Fhlor (b. Curaçao 1947, emigrated to Israel 1970), with the participation of Rahel Dahari-Amar, Sigal Eshed, Shula Keshet, Tikva Levy, Ahuva Mu'alem, Shuli Nachson, Zmira Poran-Zion, Dafna Shalom, Meira Shemesh, Esperance Shenhav, Chen Shish, Parvin Shmueli-Buchnik, Rina Shmuelian, Naomi Siman-Tov, and Orna Zaken.

Summary

The phenomenon of equal opportunity that emerged in the 1970s led, over the years, to an ever more conscious presence of women artists in the Israeli art world. The postmodern blurring of distinctions between high and low made it possible to propose an artistic analogy to women’s crafts. In this way women artists expropriated women’s work from its instrumental, perishable, and altruistic purpose and eternized it in artistic activity that was aesthetic in purpose, communicative, and self-aware. Together with modes of work developed by male creative power, female art was introduced into Israeli culture as being of equal value.

Besides the creative domains, the massive involvement of women in the Israeli art world also encompassed the major bases of influence: the domain of curatorship (in museums, galleries, and as independent curators) and the domain of writing (criticism, theory, and research). By the end of the millennium gender was no longer a relevant factor for the acceptance or rejection of women artists in Israel, and indeed today they are many in number and their influence is great, in a rich expression of the diversity of women’s voices.

Nevertheless, it is not enough. For a form, object, tone, movement, or projected image to receive meaning, it must be part of the symbolic system. The artistic object is understood only within the discourse and not before the discourse is established. Therefore, the role of feminist interpretation (in addition to class, gender, race, and religious intepretations) both contemporary and retrospective, is to animate the discourse. To generate a gender discourse today, a position in the discourse and in the art scene must be established concurrently. Only an interpretive consciousness can yield a new symbolic order—an order, as inspired by Bracha L.Ettinger, that would include not only the absent woman but also a matrixial place for women and men alike. The twenty-first century opened with great promise regarding variety and inclusivity, but the road to realization remains long and winding.

Sources: Essays in exhibition catalogs and review articles from the press, by:

Sarah Breitberg-Semmel, Galia Bar-Or Dana Gilerman, Ellen Ginton, Yael Guilat, Direktor, Kobi Harel, Ofer Ze’evi, Tami Katz-Freiman, Itamar Levi, Haim Maor, Rivka Meir, Dalia Manor, Ruth Markus, Sivan Rajuan-Shtang, Yehudit Revah, Tali Rosin, Ro’ee Rosen, Liat Arlett Sides, Smadar Shefi, Hadara Shaflan-Katzav, Ilana Teicher, Ilana Tenenbaum, Tali Tamir, and WGA digital archive.

Diti Almog

In the late 1980s Diti Almog (b. Israel, 1959) exhibited paintings dealing with the destruction of “the reality effect,” with representation of the impossibility of representing, with presenting the act of depiction as a collection of stratagems. In her paintings much stress was laid on the seductive and sensual charm of painting.

In the early 1990s Almog painted patterns of women’s clothes, proposing an analogy between woman and the art work as eluding any masculine, as-it-were objective attempt to determine her qualities and her worth. Here Almog touched on the reflexive relations present in the act of acquiring an art work, giving prominence to the latter’s “female” quality of beautifying and glorifying its possessor.

In later works Almog reduced the number of formal components and presented panels of plywood painted black, on which she painted glittering pieces of jewelry that seemed to be cushioned in black velvet, arousing associations of female sexuality. By “stitching” white thread into the panel, she created a division into geometrical areas. The result was a sterile beauty, lacking vitality or sensuality. While in earlier works she had dealt with relations between woman and her possessor, in these works the “woman” stood on her own, opposite herself, with a cold and proud façade, and only the stitches inside her bore silent evidence of the pain and the price that she pays for her beauty.

Jenifer Bar-Lev

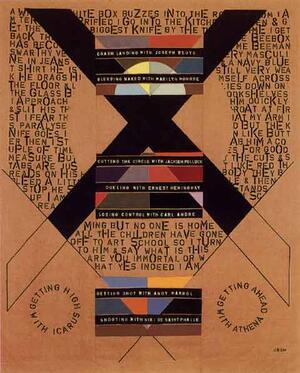

After studying design in New York, Jenifer Bar-Lev (b. United States, 1948; immigrated 1975) arrived in Israel and engaged in designing fashion textiles. Bar-Lev’s first canvases contained texts and dealt with stories connected to the feminine world of sewing. Her next works extended these boundaries and dealt with American life, with her private world, and with the world of art and artists.

Bar-Lev’s works are ornamental and decorative, containing words, ideas, allusions, barbs and witticisms—a sophisticated harmony of content and form, a clean, geometrical aesthetics with a strong tendency to symmetry. Her sources of inspiration were pattern paintings from American folk art (patchwork), Mexican and Native American art, stained-glass windows, Russian Constructivism, and Pop Art that made use of the printed letter as a message and a texture. Bar-Lev integrated sets of geometrical patterns with writing reminiscent of fragments from a private diary, impressions and memories of childhood, but also some almost Surrealist texts. The viewer-reader was invited to an intellectual and experiential journey, through the history of art, with references to literature, poetry, cinema, and performance art. The texts, written in English, were printed in stenciled letters and tended to obey the rules of structure dictated by the forms: they are broken apart, separated and re-organized into other forms. Not infrequently the viewer encounters parts of words or even isolated letters that one has to recombine into a continuous sequence of text.

In the early 1990s Bar-Lev held an exhibition in which she once again emphasized feminist messages. As a metaphor for a woman—“All glorious is the king’s daughter within the palace” (Psalms 45:14)—she built an exhibition in a room, which revolved around three circles: needlework and fabric as a “low” feminine characteristic in contrast to oil painting as a “high” masculine characteristic, low (“feminine”) folk art in contrast to the (“masculine”) intellectual and psychologistic implanted in the works, and the writing of dreams as a feminine and intimate personal writing, in contrast to the biblical text, which appeared here for the first time in her work, characterizing masculine writing.

Adina Bar-On

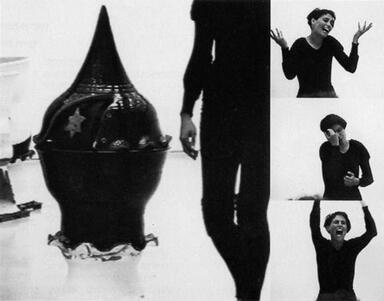

The performance works of Adina Bar-On (b. Israel, 1951) were sequences of movements that she executed with her face and body while relating to the audience and the space in which she performed. The gesture—her language of communication —remained open to the viewer’s interpretation.

In the early 1970s, against the background of the conceptual atmosphere and concurrently with the rise of the performance arts, Bar-On, then a student at Bezalel, began groping for a way to abstract the word by means of her body. Her first performances, inspired by the cinematic works of Fellini, Godard, and Buñuel, were influenced by their psychologistic ideas and unique visual conceptions. She directed, moved, danced, acted, and revealed her emotions, while the viewers to a large extent determined what she did, and it was their interpretations that built the plot.

In the early 1990s Bar-On and her husband Daniel Davis put on a multi-media performance: a video film, huge pots, voice, movement, and music. The performance presented a number of time-lines that moved in a cyclicality and a circularity emphasized by rounded objects, such as the wheels of a burial cart, rounded pots, plates, and the wheel of the sun that rose and set during the time of the performance. During the entire performance a soundless video film, filmed by Bar-On, was screened. The actions in the film repeated themselves and created an inner rhythm similar to Bar-On’s dance movements in the performance. Her children represented life and pushed a burial cart that symbolized death. The film presented a time-line of a single day—from dawn to night—and created a connection between life and art.

Deganit Berest

In her art work, which began in the 1970s, Deganit Berest (b. Israel, 1949) made use of photographs and of elements that mediate between her and the art work. Berest used her raw materials as images and signs, which she processed with the aid of devices and conventions from the fields of journalism, graphic art, and literature. Images drawn from low contexts became an artistic composition with characteristics of scientific inquiry and search. Berest enlarged common images in a way that created vagueness, blurring, and a transformation of the legible and familiar.

In the 1980s Berest created paintings dealing with man-world relations and with man’s struggle to understand the world, with sea and landscape functioning as his metaphors. The guiding principle in this period was the use of a reservoir of schematic signs of variegated forms charged with suggestive meanings. Her paintings were influenced by mathematical and physical theories, which attested to her belief in the connection between science, art, and philosophy on the one hand, and systems whose terms are transformable, on the other: expressing things in one sphere in terms taken from another sphere. Science, for her, is a kind of formula, an abstract pattern that aims to impose some kind of organization on the chaos of nature, a way of exposing the world’s structured nature, and thereby to touch its beauty and its magic.

Berest’s use of aspects originally attributed to women, such as working with repetitive patterns, together with conceptual aspects that are considered masculine, such as scientific theories, created an androgynous model, which was declared as such by the artist.

In an exhibition of her works in the late 1990s, “The Montageuse or Broken Telephone,” Berest dealt with the more revealing and erotic side of her work. A systematic process connected with the motif of blurring-camouflage-mask continued to appear in her work in various ways and expressed an opposition to a cataloguing of identity according to a ready recipe, the freedom entailed in choosing to stem from a system that would be defined after the event, in which the methodical, analytical, rational dimension is part of her personal composition of what is feminine, masculine, Israeli.

Miriam Cabessa

Miriam Cabessa (b. Morocco, 1966; immigrated 1969) began her artistic path in the early 1990s. Her images, which were painted in a process of movement, through action and an inner rhythm, created a language of signs similar to techniques that had been developed by the Surrealists. Unlike them, however, Cabessa made herself the subject of her paintings by involving her body in the work process and created images that express what was happening inside. These looked like X-rays that reflected ultimate female images possessing great power. In this way Cabessa created a language in which she expressed the writing of her own body, a body that knows its own rhythm, libido, and eroticism. On the face of it, Cabessa turned her body into a production line that works automatically, but actually she created voided limbs, hollow tubes, hands seeking a place to hold on to, legs seeking a place to touch, a penetrating view into the inside of the body, slightly obscene, somewhat alienated.

Mirit Cohen

In the early 1970s Mirit Cohen (b. Russia, 1945, d. 1990) worked on heavy, rough wooden panels, which she wounded by incising, drilling, and breaking them, at times pasting on pieces of paper. In opposition to the art conceptions of the time, which saw wood as a surface, Cohen treated wood as equal in value to paint.

In the 1970s Cohen’s drawings created maps of graphic signs and of words and parts of words. The words functioned as additional components of her drawings and lent them a quivering nervousness. With the aid of the script signs, Mirit Cohen conveyed changing and elusive information through a technique of breaking up the words.

In an installation, Cohen laid pieces of broken glass and broken floor tiles, tied together with electricity wires, on the gallery floor. In these sharp, cutting works, laden with wires and shards, the artist attempted to group together what looks like a desperate and hopeless attempt at a fusion.

In the fifteen years prior to her suicide in 1990, Cohen lived in New York. During her stay there she held an exhibition in Israel of a series of small drawings titled “Mind Script,” which looked like maps of nerves in a tortured brain.

After Cohen’s death, a retrospective exhibition was held in her memory at the Israel Museum. As the artist Joshua Neustein described her: “She worked with a Dadaistic sensitivity, but brought to art the horror, the religion and the sexual fantasies that she took from her life… Everything broke free and went loose like the web of a spider gone mad. The order of the web became jumbled and the center collapsed.”

Maya Cohen-Levy

From her stay in the Far East—India, Japan, and China—and from her art studies there, Maya Cohen-Levy (b. Israel, 1955) absorbed an approach of spontaneity and immediacy within traditional formats, a use of mathematical patterns with an aspiration to reductiveness, a focus on a single image and subject, and a simple and repetitive composition.

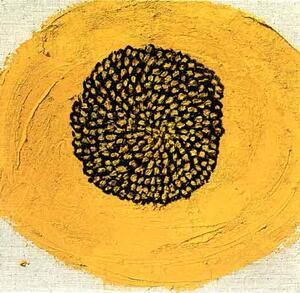

In the early 1980s, Cohen-Levy exhibited an expressive painting that depicted an imaginary carnival of lizards with their tails in their mouths. Inside the circular flow produced by the lizard’s movement around itself, the artist created a powerful focus, which, however, unified a number of contrasting points of view. Cohen-Levy’s works dealt with an inscrutable secret. Each of the images was presented in close-up, enlarged and spread out over the surface, for a detailed and systematic representation of its “anatomical” components as they are in nature.

In the early 1990s, Cohen-Levy created series that ably demonstrated the precision and streamlining she had achieved in a long process of reduction of both ideas and forms. In the “Heart of the Sunflower” series, for example, she created large close-ups of the spiral center that grew from the sides to the center and in the opposite direction. The spiral is considered one of the primary forms of order and harmony in the cosmic code. The “Honeycombs” series was built of an overlapping array of bees’ antennae that were painted repeatedly in various arrangements and degrees of transparency, which turned into crystals and produced the form of a Shield of David from within themselves. Even the “Palms” series, which again uses a basic form (the palm tree) that is spread out and fills the entire format while engaging in a scientific and artistic search for order and for control of the energy contained in the form, represents an aspiration to expose the essence.

Nurit David

In the early 1980s Nurit David (b. Israel, 1952) created a series of pictures on plywood panels and wax cloth, in which she integrated motifs from a remote, representative, and symbolic world, the fruit of her imagination and her personal world.

Later David engaged in an attempt to combine the written word and the image, the way it is possible to show a language written on a surface, while the name of the series (“Father”) hinted at an autobiographical interest. These monochrome conceptual works were done on plywood panels and incorporated countless matches and letters that were pasted on the surface and created a relief.

In the early 1990s David emphasized the importance of the text in her painting in a different way. In these works, she recorded mental and emotional occurrences that arose while being absorbed in the words that built her existence as a human being and spoke about the person/the parent who contains the works of painting within his body and creates himself in the course of his creative work. In these works she combined various materials and photographs connected with her family, with the aid of which she created painted and written paths that look like cognitive maps of the field of the psyche.

From the mid-1990s on, David created, in oil on canvas, realistic-factual paintings that are rich in images and have a psychological power that crossed to the spiritual and the surrealistic. Whereas in her earlier works her family and biography had been present as an abstract concept, she now brought these onto the canvas. David quoted motifs from her monochrome paintings of the mid-1980s, in a different technique than she had used in the original, and added autobiographical items, using an intimate, everyday touch that was also ritualistic in the way she presented them, looking as though they were lying in memorial corners. She presented the place of the written word by means of blank notebooks that were incorporated into the painting’s background and symbolized the artist’s refraining from speech and writing because of her aspiration to return to non-verbal contemplation.

Drora Dominey

When Drora Dominey (b. Israel, 1952) returned to Israel from England in the early 1980s, she became one of the instigators of the breakthrough by new young sculptors. Her sculpture was the antithesis of the heavy sculpture of stone and “place” hitherto created in Israel. Dominey created light and elegant sculptures of bare wood, at times painted, executed with high skill, alluding to living creatures and furniture/architecture/design elements, influenced by the Bauhaus and De Stihl, based on a long tradition of Constructivist sculpture. The sculptures, done by a woman in a masculine tradition, were a remonstration against what was considered feminine. The sculpted objects were perceived as objects that had had their usefulness taken from them and had been accorded an enigmatic, cold beauty.

Later, a sex-death tension entered Dominey’s works through motifs of splitting and separation between masculine and feminine representations. Masculine impetus and feminine introversion existed side by side in her works as complementary qualities.

In the 1990s Dominey exhibited sculptural objects taken from the image treasury of the “home,” possessing an autobiographical/nostalgic dimension. Dominey broke their functionality by introducing some kind of distortion into each object and created an estrangement of the viewer’s body through an experience of incorrect size, unpleasant touch, morbidity, and awkwardness. The atmosphere was of cool eroticism, and a tension existed between the rounded feminine and sharp, straight masculine lines, between the formalism/design and the human story on the one hand, and the artist’s pain and self-examination on the other.

In the mid-1990s, Dominey held an anti-sculptural exhibition of old and faded objects, Readymades from the feminine/maternal world of images, with a dualism of story and conceptual idea. Transformation of forms from one sense to another, from a geometrical form to an object or a linguistic sign, is essential for an understanding of her work. The tension between large arches and circles that abound with meanings—pearls, punctuation marks, haloes, bullet holes—is a tension between a form and a symbol, a story. In her later work, Dominey returned to formalistic construction of large and challenging objects and to the use of unconventional sculptural materials that simultaneously contain images and meanings of a feminine, biographical, and national story.

Smadar Eliasaf

In the 1970s, Smadar Eliasaf (b. Israel, 1952) engaged in photography. Artist Nurit David, in her essay “From Refined Contempt to a Kiss,” pointed to morbid and pessimistic elements in Eliasaf’s photographic works—images blurred to the point that their identity is lost, pieces of broken glass, words functioning as torn scraps of reality.

Eliasaf gave quasi-poetic names to her large, many-layered, expressive and abstract paintings on canvas, which she began creating in the late 1980s. The large brushstrokes have unraveled edges, which recall the quality of unreality and illusion in her photographs of the 1970s. Her paintings, done on the floor as in Action Painting, and the stains that spread and float over them, recall the American abstract art of the 1950s.

After using strips of sponge, Eliasaf turned to items of personal clothing dipped in paint, which she dragged over the canvas. The stains seem to be in constant though distant movement. The expressionism, which had been modified by mediators, changed its color from the grays in the early paintings to bold and assertive colorfulness in the 1990s.

Bianca Eshel-Gershuni

Bianca Eshel-Gershuni (b. Bulgaria, 1932; immigrated 1939) began making jewelry while still engaged in her sculpture studies. In the late 1970s, the Israel Museum held an exhibition of her jewelry. At the time she was already making unconventional pieces of jewelry, which combined expensive materials such as gold and precious stones with cheap materials and depicted little scenes. Richness and splendor, imagination and fable characterized the jewelry she made during the minimalist and conceptualist period in Israel, counter to the “poverty of material” approach that characterized Israeli art at the time.

In the early 1980s, after a personal crisis, Eshel-Gershuni began making pieces of jewelry that she called “Fetishes.” These “Fetishes” recalled voodoo rites and the use of black magic. In the mid-1980s, Eshel-Gershuni showed her “Mourning Cycle,” which centered on the battle of the sexes and a perception of the world from the depths of the position of the feminine psyche. Her image of woman, man’s eternal victim, was remote and different from a feminist and modern awareness. Her rebellion found expression in weeping and mourning, which she expressed through folkloristic elements and quasi-ritualistic objects. Above the image of woman as a victim stood the image of woman as Eve, mother of all humans, sensual and overflowing, and this image determined the work’s character. Eshel-Gershuni also used Christian, pagan, and tribal motifs integrated with one another. The spectacular ostentatious abundance of material and creativity in the works expressed her distinctive treatment of kitsch, which she harnessed as a means of expression and used to create a correspondence between the dreamlike, beautifying side of reality and the falsity of the romantic, feminine, and idealistic view of man–woman relations. Her manipulative and sophisticated use of materials identified as feminine kitsch was a daring breakthrough for young women artists in whose works her influence is discernible.

From the early 1990s on, Eshel-Gershuni held exhibitions in which the turtle was the central motif. The woman who carries her home on her shoulders is the ideal woman, as bourgeois society attempted to fixate her. The image produced symbolized the cyclicality of Creation, of nature, of life and death. The turtle has a time of its own, and its slowness is both its strength and its weakness, another quality with which the artist identified.

Dorit Feldman

In the 1970s, Dorit Feldman (1956-2020) studied at The Midrasha, the Art Teachers’ Training College at Ramat Hasharon; during the 1980s she continued her studies at the Institute of Kabbalah Research in the Faculties of Humanities and Art History at Tel Aviv University. In 1987 she attended the MFA Program of the School of Visual Arts, New York, international studies, in Urbino, Italy. This interdisciplinary background intensified the conceptual approach combining concept-body and earth that had characterized her work from the beginning. Her Body Art series (1979-1980) dealt with eco-feminism and pursued the unification of the cosmic categories of women/nature with women/man as a whole entity. The images that Feldman employed included formal codes from ancient cultures that had developed ways of storing information and arriving at simplification and miniaturization while at the same time containing a kind of "hide knowledge." From Kabbalistic mysticism and structures, basic forms, trigrams of the Chinese I Ching, or “matrices” (coded squares) of the Mayan culture, to computer chips, DNA molecules, and code signs in futuristic orientation—all these served her as very powerful signs of knowledge, as materials for the artist to work with.

Feldman’s prolific career over several decades focused on images of wide landscapes that integrate geological, cartographical, and archaeological layers. Images of abstract topography that are at the same time made concrete and symbolic landscapes appeared in her video art "The language of the stones" (2018), based on the partiture of Zipi Fleisher. These geo-philosophical territories present a combination and abstraction of Dead Sea landscapes, the Zin desert, Ramon Crater, Wadi Kelt, the Judean Desert, and Qumran caves and are simultaneously realistic and abstract. As Nava Sevilla Sade notes, "A highly significant aspect is that of the unique aesthetic created by the artist through her collages of mixed media, incorporating photography, painting, engraving and sculpture. The painting assimilates into the photography and thus becomes homogeneous, as an immediate metaphor of primeval geological layers" (Sevilla-Sadeh). Feldman welcomed collaborations with creators from various fields, including writers, poets, and scientists, and her oeuvre can be described as "art-based research."

Tamar Getter

In the 1970s Tamar Getter (b. Israel, 1953) dealt with monumental topics (such as the Tel-Hai myth) and myths connected with communications and with political and social events. These were placed beside terms from other times and cultures, creating a broad perspective. Getter gave the abstract concept of the heroic myth an emotionally restrained visual expression, influenced by the early Italian Renaissance conception of painting. She employed a diversity of spatial conceptions, techniques, and approaches, a kind of collage combining classical conventions of representation and conceptual art. The painterly-intellectual challenges she took upon herself in the 1970s continued to find expression throughout the years: an aspiration to combine highly imaginative personal images with a painterly-structural conception; constructive representation of an irrational world of images; correspondences between old and new images; and the creation of classical contexts by means of juxtaposing charged Israeli motifs with quotations from Renaissance masters.

Getter’s choice of colors and composition is always connected with the Israeli light and landscapes, but also with the faded and ruined frescoes she saw in Italy. She translates these two sources with emphasized outlines, loss of details, and flattening.

In the 1980s, Getter added gender images to this rich iconographic and intellectual treatment of means and “poor” materials that represent relations between men and women.

In the late 1980s Getter abandoned plywood and printed paper in favor of canvas and color, gave up building clear compositions, and created a colorful anarchy while emphasizing the banal and clichéd aspect of academic painting. Yet she remained a conceptual artist, continuing to use images from the memory of art and from the collective cultural memory.

Pesi Girsch

Pesi Girsch (b. Germany, 1954; immigrated 1968) separated photography from the processing by adding a narrative and built—formally and experientially—a reality from basic elements such as man, earth, water, and sky. She created a synthesis of Hellenistic sculpture that is found with limbs broken off, influences of the body’s sufferings in the sculptures of Michelangelo, and the plasticity of the figures in the photographs of Mapplethorpe.

In the overall Israeli photography scene, Girsch’s photography stood out as a foreign implant with distant cultural sediments. The influence of her childhood in Germany found expression in her works in the representation of the tension between Christianity and Judaism and in expression of the Jewish people’s path of afflictions, pursued by Christian symbols. These contents were poured into polished patterns, with stylized figures frozen in them. She designed and photographed complex ceremonies of distortion and death with quasi-pagan rites with a clean meticulousness.

The ritualistic scenes in Girsch’s works from the late 1980s and early 1990s had a hallucinatory Surrealist appearance that verged on the macabre. The severed limbs and the almost “acrobatic” bodily tension of the attenuated bodies in her works were associated with photographs of victims of the Holocaust.

In the late 1990s Girsch exhibited photographs of yards in an ultra-Orthodox neighborhood in Jerusalem and photographs from Dachau, Germany. Beside enthusiasm about the beauty of the old yard, prominence was given to the awareness that time there had stopped. Her ability to remain a foreigner in her own homeland enabled her to present to the spectator a view of reality that reflects a central problem—the increasing disparity between the self and the Other.

Girsch’s photographs of dead chicks entailed acts of collecting, sorting, and reshaping. While in her previous series the flowing continuum of life was frozen, here what was frozen looked vital, but in the harsh presence of death. The place could be interpreted as Germany, with all its connotations.

Nechama Golan

From the beginning of her career in the 1990s, Nechama Golan (b. 1947) operated in a complex reality. On the one hand, her worldview became Orthodox; on the other hand, the artistic institutions in Israel were strictly secular, suspicious about the possibility of the development of art within the framework of The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah. As were other newly Orthodox Jews, or ba'alei teshuva, she was capable of manipulating a wide set of both secular and religious concepts. Her feminist artistic language was thus complex and layered, and she opened the door for other religious women artists.

In Golan's world, the word became a carrier of material essence, an artistic icon. In her hands, religious ceremonies and rituals became the object of an observant and inquisitive gaze. Over the years, Golan created an extensive and impressive body of work that includes installations, sculptures, and many works in mixed technique. She never hesitated to criticize elements in Jewish customs and laws that deserve criticism, and not an escape from touching "sacred matters." Her works decorate the covers of books of poetry and prose, and the manipulated photoprint "Women's Book" (2000) and the sculpture "You Shall Walk in Virtuous Ways” (1999) have gained iconic status. As David Sperber notes: “As a radical piece that does not align even with accepted practices in Orthodox Jewish feminist discourse. Like many works, Golan’s art does not simply duplicate practices of resistance or political strategy. In fact, she offers a more direct and detached position than is the norm in Orthodox Jewish feminist discourse. Golan uses materials that allow her to articulate a view that should not be verbalised in Jewish religious spaces"( Sperber).

Michal Heiman

In the 1980s Michal Heiman (b. Israel, 1954) worked concurrently as both a painter and a photographer. She exhibited paintings on plywood that were rich in texture and color, while as a photographer she worked on a series of enlarged and duplicated newspaper pages that dealt with the connection between authenticity and communication. She reappropriated photographs she had taken that had appeared in the newspapers and displayed them in artistic spaces and contexts. The works reported ironically about the absurdity of the attempt to demolish traditional romantic values such as the freedom to create, authorship of a work, originality, and authenticity.

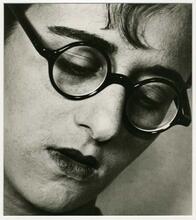

In the early 1990s, Heiman exhibited photographs/objects in a space where the organization and atmosphere evoked the feeling of a memorial room. The photographs, which had been taken from family albums, were attached to transparent boxes and showed signs of having been pulled out of the album in which they had originally been viewed in an innocent and primal way, to be placed in an anonymous, public viewing space. In the 1990s Heiman showed works that connected with psychology, Kabbalah, concealment, masks, and ambiguities. These works had modes of symbolizing that Heiman took from Tarot cards, alternative medicine, literary texts, etc., added to the idea of cruelty and loss of life and to the idea of the separation of the mind, the understanding, the spirit, and logic (the head) from matter, the flesh, impulses, and desires (the body). The portrait of artist Aviva Uri recurred in her works; through her Heiman dealt with motifs connected with woman/mask/woman artist/story/nightmare/physical death/cultural death.

In the late 1990s Heiman created a kind of alternative “test” based on the T.A.T. (Thematic Apperception Test) used for psychological diagnoses. Her installation was built as a station where the M.H.T. (Michal Heiman Test) was held. In her opinion, the test presented a situation analogous to the art world but also entailed a closed system of contemplation and interpretation. While the viewer of an art work is required to be active and to face his/her own fears and wonderings, Heiman invited viewers to a dialogue, through which they could give expression to their thoughts. By turning viewers into patients or people being diagnosed, she reconstructed an intimate quasi-therapeutic situation and dealt with the point of interface between psychology and the museum and with the essence of the image and of identity.

Eti Jacobi

In the late 1990s Eti Jacobi (b. Israel, 1961) exhibited her first paintings, which entailed a connection between classical painting and Disney Studios’ animation paintings. Critics related to these images as an expression of Israeli art’s sense of remoteness from European art, because of their secondary nature and a capacity that seemed limited to no more than chatter on the margins of beauty. Paintings on subjects taken from Greek mythology after the French classicists were given childish names from inscriptions on playing cards or from the world of fairy tales. In this way they became “a marvelous world.” By using animation and movement, which are absent from classical painting, Jacobi breathed life and magic into historical painting.

Jacobi thus examined the hierarchy between classical painting and the enchanting painting of Disney, the mixing of the French and the American traditions, the viewing of classical historical painting from the point of view of a child. The blurring of boundaries highlighted a number of contrasts: adult/child, high/low, masculine/feminine, light/heavy, figurative/abstract, pleasing/painful.

Shula Keshet

Mizrahi feminist activist, artist, and curator Shula Keshet (b. 1959) was born in Israel to a family from Mash’had, Iran. She is a leading figure in several social movements striving for justice for underprivileged men and women in Israel. Keshet was a founding member of the Mizrahi feminist group “Achoti – For Women in Israel” and has served as editor-in-chief of Achoti Press. As a Mizrahi feminist artist and curator, she has initiated several exhibitions. Her exhibitions “Black Labor” and “Women Creating Change” embody the principles behind the vision and activism of Mizrahi feminist politics. “Black Labor” was based on a series of meetings, art events, and mutual-learning sessions for groups of Mizrahi, Ethiopian, Palestinian, and Bedouin women artists. “Women Creating Change” contained the portraits of 38 feminist activists working in the community and academia.

Liliane Klapisch

The painting of Liliane Klapisch (b. France, 1933; immigrated 1969) evolved from the abstract painting of the 1950s in France but preserved an affinity for classical art and observation of nature. In order to shift from abstract to figurative painting, she learned what she dubbed “the grammar of nature,” which she found in the landscapes of Poussin and in a connection to nature filtered through culture and geometry. Klapisch drew studies outdoors and painted her canvases in the studio, with a limited and at times turbid scale of colors.

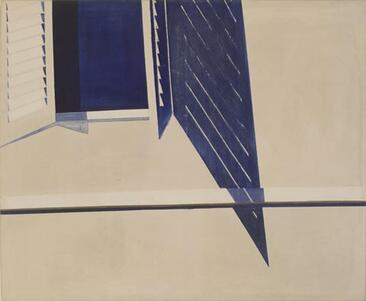

Klapisch’s paintings contain an inner tension between nature and intellect, between the organic and the conceptual, between interior and exterior. Choosing subjects connected with her surroundings—a cityscape, backyards, construction sites—she drew the viewer in by means of motifs that conduct the eye inwards, such as trees, parts of houses, and strips of paint that took on the role of the window that appeared in many of her paintings. Her compositions tend towards symmetry and harmony, but the brushstrokes have an expressive momentum and reveal an emotional or sensual way of relating to the painted objects.