Judy Chicago

As a young artist in California, Judy Chicago initially produced impersonal Minimalist work like Sunset Squares (1965). But 1970s feminism quickly inspired her to pivot her thinking. Ever since, she has imbued her art with subject matter for which she is passionate and has emphasized her personal perspective as a woman. Through painting, sculpture, drawing, performance, writing, teaching, and large-scale collaborative projects (such as The Dinner Party, 1974–1979), she has become one of the most recognized artists and significant voices of contemporary western culture.

As a young artist in California, Judy Chicago initially produced impersonal Minimalist work like Sunset Squares (1965). But 1970s feminism quickly inspired her to pivot her thinking. Ever since, she has imbued her art with subject matter about which she is passionate and has emphasized her personal perspective as a woman. Through painting, sculpture, drawing, performance, writing, teaching, and large-scale collaborative projects (e.g. The Dinner Party, 1974–1979), she has become one of the most recognized artists and significant voices of contemporary western culture.

Beginnings

Born Judith Sylvia Cohen on July 20, 1939, in Chicago, Illinois, she later broke with patrilineal tradition by adopting the surname Chicago. To explain her seemingly innate belief in herself and her dismissal of sexist stereotypes, Chicago has pointed to the lack of gender bias in her family. An avid Marxist, Chicago’s father, Arthur, encouraged his only daughter to participate in the political discussions that pervaded their middle-class home. Although descended from twenty-three generations of rabbis (one of whom was the eighteenth-century Lithuanian rabbi the Head of the Torah academies of Sura and Pumbedita in 6th to 11th c. Babylonia.gaon of Vilna), Arthur elected to reject Orthodox Jewish life. Meanwhile, Chicago’s mother, May, an erstwhile dancer, prompted Chicago and her younger brother, Ben, to pursue artistic interests.

Feminist Awakening

Chicago’s art education commenced at the Art Institute of Chicago and continued at the University of California at Los Angeles, where she completed a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1964. Her marriage to Jerry Gerowitz in 1961 ended tragically when he was killed in a car accident two years later. Chicago explains that she turned to art for solace. And she produced Minimalist sculpture with the hope of gaining acceptance from the male-dominated art world. Soon, however, she changed her objective, stating: “I could no longer pretend in my art that being a woman had no meaning in my life” (Through the Flower, 51). Subsequently, Chicago started to explore what it meant to be both a woman and an artist.

Pedagogy

Wanting to aid other women on their artistic journeys, Chicago developed the Fresno Feminist Art Program at California State University-Fresno in 1970. Artist Miriam Schapiro began to collaborate with her the following year, when the program was moved to the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. Here, their female students relied upon personal experience for subject matter, culminating with the exhibition Womanhouse (1972), for which students and teachers transformed a local dilapidated house into an impermanent, ground-breaking art space. The rooms, closets, and hallways became art installations and performance venues. Every component, such as Chicago’s Menstruation Bathroom, conveyed the particular perspective of each artist as a woman.

The Dinner Party

With the 1970s women’s movement in full swing, Chicago became increasingly disturbed by the absence of women from historical accounts. She eventually separated from her second husband, Lloyd Hamrol, and launched an investigation that uncovered a wealth of important women who had been neglected by historians. Chicago resolved to honor many such women in a monumental, three-dimensional work that became The Dinner Party (1974–1979).

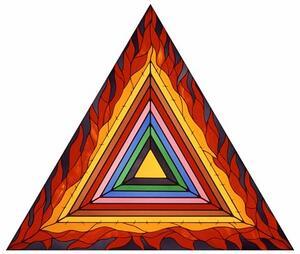

Hundreds of volunteers researched, sewed, painted, and assembled in order to re-insert women (such as the Jewish heroine Judith and the Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi) into the cultural narrative. In the end, The Dinner Party symbolically brought thirty-nine overlooked women to the table, with personalized place settings that included embroidered runners and original vaginal-butterfly-designed ceramic plates. Each setting connotes an honoree’s historical contribution and earmarks a spot around a large triangular table. Acknowledging that many other neglected women were deserving of inclusion, the piece sits atop the names of hundreds of additional potential guests.

Initially, the sexually suggestive imagery of the plates stirred up controversy, but The Dinner Party has become an undeniable, empowering landmark in feminist art history. The Brooklyn Museum of Arts purchased and permanently installed The Dinner Party in 2002; by that time, the work had been seen by more than a million people in six countries on three continents.

The Birth Project

Creating iconographic imagery where little had existed before is a pattern in Chicago’s artwork. Upon noticing that the birthing process was seldom depicted in western art, Chicago decided to portray it in a new communal endeavor entitled The Birth Project (1980–1985). She designed images of women in labor that were then translated into needlework by women across the United States. The goal, asserts Chicago, was to recast the story of Genesis by challenging “the notion of a male god creating a male human being with no reference to women’s participation in this process” (Beyond the Flower, 84–85).

Jewish Identity

Chicago honed her focus on the construction of masculinity and its relationship to power in the multi-media series Powerplay (1982-1987). This course of inquiry compelled her to face the tragedy of the Holocaust and profess her insufficient knowledge about the genocide, as well as about her Jewish heritage. Settling in New Mexico, Chicago planned to explore her Jewish identity in tandem with her soon-to-be husband, photographer Donald Woodman. By the time they were married on New Year’s Eve 1985, the couple had agreed to unite their efforts in order to visually represent the Holocaust—a subject rarely broached in fine art.

After years of study, Chicago and Woodman produced The Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985–1993), a mixed-media installation that confronts formidable issues surrounding the abuse of power and its horrific manifestations. Like all of her projects, this one touched and educated many viewers as it traveled.

Chicago has also celebrated Jewish life, producing Lit. "sanctification." Prayer recited over a cup of wine at the onset of the Sabbath or Festival.kiddush cups, Unleavened bread traditionally eaten on Passover.mazzah covers, and Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder plates. Typically, these pieces reflect Chicago’s feminist mindset, highlighting, for example, the significance of Miriam, Moses’ sister. In 2018 she created the series “Cohanim” to commemorate singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen, his lyrics, and their shared last name.

What if Women Ruled the World?

In 2001 Chicago completed her final group endeavor, Resolutions: A Stitch in Time, a series of painted and needleworked images reinterpreting traditional proverbs, whereby Chicago intended to “present images of a world transformed into a global community of caring people” (Beyond, 262). Indeed, as Chicago suggests, it is the Jewish concept of tikkun olam—the healing of the world—that motivates her most profound art. It might have been this overriding philosophy that prompted her to travel to China to take part in a five-month-long international art project in 2002. Together, Chicago and the other participants worked to envision what our planet could look like “If Women Ruled the World.”

That query, “What if women ruled the world,” became the focal point of Dior’s haute couture Paris show in 2020, when Chicago collaborated with the fashion house’s creative director, Maria Grazia Chiuri. Viewers watched the extravaganza from within the giant womb-like space of an inflatable goddess while models strutted the runway, past embroidered banners that carried responses to the question with phrases like “Would There Be Violence?” or “Would God Be Female?”

Impermanence

Periodically, Chicago experiments with such ephemeral media as smoke and gaseous forms. In 1967, she co-created Dry Ice Environment #1, a kind of public Happening that took place in Los Angeles. Similarly, in her Atmosphere works, Chicago purposefully turned to pyrotechnics to counter the environmental damage caused by contemporary Land Artists, a movement especially popular in the 1970s. The results produced majestic multi-colored swells of smoke. “There was a moment,” Chicago reminisces, “when the smoke began to clear, but a haze lingered. And the whole world was feminized–-if only for a moment” (Gotthardt).

Chicago has occasionally gifted several cities with a giant, temporary, transforming Butterfly made of fireworks, as seen in A Butterfly for Brooklyn (2014). Over 10,000 viewers watched that performance in Prospect Park, and near its conclusion they spontaneously broke into song to wish Chicago a happy 75th birthday.

Chicago’s ongoing acknowledgement of temporality—in regards to life itself—is bravely confronted in her 2019 exhibition “The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction.” With this show, Chicago continues her lifelong wrestling with uncomfortable, yet profound, subject matter. Included are harrowing paintings that contemplate the specifics of our/her inevitable demise that simultaneously parallel the destruction of the planet and the deplorable extinction of other species.

Legacy

In 2003, Duke University awarded Chicago an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree. She received the Visionary Women Award from Moore College of Art & Design and the International Lion of Judah Conference Award for Pioneering American Women Jewish Artists a year later. Time magazine listed Chicago as one of the “100 Most Influential People” in 2018, the same year that Artsy Magazine named her a “Most Influential Artist.” The following year, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago granted her the Visionary Woman award.

The Judy Chicago virtual Research Portal was established with the proclamation: “As part of her efforts to overcome the erasure that has eclipsed the achievements of too many women, Judy Chicago has placed her archives with four institutions”: Center for Art + Environment Archive Collections at the Nevada Museum of Art, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Penn State University Libraries, and Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College.

Still, Chicago perseveres, responding to the 2020 pandemic quarantine with a new series of prints entitled “Confined” that are exhibited at her Through the Flower art space in Belen, New Mexico. To make these “Garden Smoke” images, Chicago set off private colored smoke sculptures in her backyard that were photographed and printed by Woodman.

In 2021, Chicago plans to release her new autobiography, The Flowering (Thames & Hudson), which contains a forward by fellow feminist icon Gloria Steinem. Like everything in Chicago’s oeuvre, this book promises to be powerfully relevant.

Selected Works by Judy Chicago

The Flowering. London: Thames & Hudson, 2021.

Institutional Time: A Critique of Studio Art Education. New York: The Monacelli Press, 2014.

Women and Art: Contested Territory, co-written with Edward Lucie-Smith. London: Weidenfeld & Niconson, 1999.

Beyond the Flower: The Autobiography of a Feminist Artist. New York: Penguin, 1996.

Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light, with Donald Woodman. New York: Penguin, 1993.

Powerplay. New York: ACA Galleries, 1986.

Birth Project (1980–1985).

The Second Decade, 1973–1983. New York: ACA Galleries, 1984.

Embroidering Our Heritage: The Dinner Party Needlework. New York: Anchor Books, 1980.

The Dinner Party (1974–1979).

Through the Flower: My Struggle as a Woman Artist. Garden City: Doubleday, 1975.

Womanhouse, exhibition catalogue (1972).

Aukeman, Anastasia. Division of Labor: ‘Women’s Work’ in Contemporary Art. Bronx, NY: Bronx Museum of the Arts, 1995.

Broude, Norma, and Mary D. Garrard, eds. The Power of Feminist Art: The American Movement of the 1970s, History and Impact. New York: Harry N. Abrams Inc, 1994.

Chan, Katherine, ed. Judy Chicago: Deflowered. New York: New York Foundation, 2013/2021.

Fields, Jill, ed. Entering the Picture: Judy Chicago, The Fresno Feminist Art Program, and the Collective Visions of Women Artists. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Gotthardt, Alexxa. “When Judy Chicago Rejected a Male-Centric Art World with a Puff of Smoke.” artsy.net, July 26, 2017 (viewed on January 18, 2021). https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-judy-chicago-rejected-male-centric-art-puff-smoke

Jones, Amelia. Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in Feminist Art History . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Levin, Gail. Becoming Judy Chicago: A Biography of the Artist. New York: Harmony, 2007.

Lippard, Lucy. From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art. New York: Dutton, 1976.

Lippard, Lucy. “Judy Chicago’s ‘Dinner Party.’” Art in America 68:4 (April 1980): 114–126.

Meyer, Laura and Faith Wilding. A Studio of Their Own: The Legacy of the Fresno Feminist Experiment. Fresno, CA: California Press at California State University Fresno, 2009.

National Museum of Women in the Arts. Judy Chicago: New Views (2019).

When Women Rule the World: Judy Chicago in Thread. exhibition catalogue. Toronto: Art Gallery of Calgary and Textile Museum of Canada, 2009.