Wendy Wasserstein

In 1989, Wendy Wasserstein won the Pulitzer Prize for The Heidi Chronicles and was the first woman playwright to win a Tony Award. In 1973, Wasserstein joined the MFA program at The Yale School of Drama and was the only woman in the playwriting program. Her thesis, Uncommon Women and Others, depicting five women friends over several years, was produced at the Phoenix Theater in New York in 1977. Wasserstein devoted her career to depicting intelligent, talented, nuanced women, such as the protagonists of her 1992 The Sisters Rosensweig. While she is mainly known for her dramas, she also wrote three musicals, various comedy skits for the television series Comedy Zone, and essays published in the New Yorker, Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, and other magazines.

In the 1960s, at the Calhoun School on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, Wendy Wasserstein discovered that she could get out of gym class if she wrote skits about the mother-daughter fashion show. In 1989, with The Heidi Chronicles, she won a Pulitzer Prize and became the first woman to receive the Tony Award for Best Play.

Early Life and Family

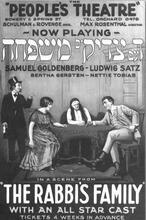

Born in Brooklyn on October 18, 1950, to Morris and Lola (Schleifer) Wasserstein, Wendy was the youngest of four children, of whom one was a son. Her wealthy and sophisticated grandparents on her mother’s side came from a Polish resort town. Suspected of being a spy, her grandfather Simon Schleifer left Poland for America, where he became a high school principal in Paterson, New Jersey, and wrote Yiddish plays. Her father owned a textile factory with his brother, where he patented velveteen. Her mother, a housewife with a passionate interest in dance and theater, took Wendy to weekly lessons at the prestigious June Taylor School of Dance. The family lived in Brooklyn until Wendy was twelve, when they moved to the Upper East Side of Manhattan.

Higher Education and Early Work

Wasserstein was a history major at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts, but when she found herself falling asleep over The Congressional Digest as she was preparing to become a summer intern for Congress, she seized a friend’s suggestion that they take a course in playwriting at Smith instead. After graduating from Mount Holyoke, she studied creative writing with Joseph Heller and Israel Horowitz at City University of New York, where she wrote her first play, Any Woman Can’t, as her master’s thesis in 1973, about a girl who forgoes a dancing career and gets married after failing an audition for tap-dancing class.

Still uncertain about her direction in life, Wasserstein almost went to law school, business school and medical school before deciding to try something she really enjoyed and entering the playwriting program at the Yale School of Drama. There, she studied no plays by women, nor did she meet a single woman director. In fact, at the first reading of Uncommon Women at Yale, a male student remarked that he did not know if he could “get into” her play because it was about women. Wasserstein thought, “Well, I had ‘gotten into’ Hamlet and Lawrence of Arabia, so why don’t you try this on for size?” Equally disturbed by Hollywood’s negative and stereotypical representation of women, Wasserstein was determined to prove that a woman need not be insane, desperate or weird in order to be stageworthy. Consequently, she devoted her entire playwriting career to exploring the lives of intelligent, talented women.

The production of her first play happened as serendipitously as her first playwriting course. When one of her mother’s friends asked how Wendy was doing, her mother started hyperventilating and in desperation exclaimed, “She’s not a lawyer. She’s not married to a lawyer. And now she’s writing plays.” The friend asked for one of Wendy’s plays in order to show it to director Robert Moss at Playwrights Horizons, an Off-Broadway theater. From that time, Playwrights Horizons was her artistic home and she served on its artistic board.

Wasserstein’s Plays

Uncommon Women and Others, first produced in 1975 as her thesis at Yale, then presented at the Phoenix Theater in New York City in 1977, and later televised for public television’s Great Performances series in 1978 and revived in the fall of 1994 at the Lucille Lortel Theatre in New York with an updated ending, introduces five women as they meet at a New York restaurant, then travels back six years to their senior year at Mount Holyoke, where they discuss their future careers, men, sex, marriage, and the fact that society is patriarchal. Uncommon Women was a landmark, the first play that treated contemporary women’s issues with seriousness. The New York Times critic John O’Connor complimented the play’s “insights into the challenges and crises confronting modern women.” Critics also praised Wasserstein’s ear for dialogue and her wicked sense of humor. Indeed, for Wasserstein, as for many of her characters, humor was a necessary bulwark against the disappointments of life.

In a slightly different key, her 1983 one-act play Tender Offer, produced at the Ensemble Theater, explores poignantly the relationship between a girl and her father. Like Uncommon Women and Others, Isn’t It Romantic, presented by Playwrights Horizons in New York in 1983, explores upper-middle class, expensively educated, single women, but Janie and Harriet are six years older than their counterparts in Uncommon Women, and they are out in the world, searching for love and professional fulfillment in Manhattan in the face of changing values. While Janie is the daughter of overprotective Jewish parents who desperately want her to get married, Harriet is the daughter of a WASP professional woman who encourages her to pursue her career.

Isn’t It Romantic received mixed reviews from New York critics. Some had trouble with the play’s episodic structure, and Douglas Watt found its conclusion, with Janie’s “dance of joy,” to be “hollow and unconvincing.” Others argued that the characters were underdeveloped. In some quarters, the play was criticized as “too Jewish”—but then, as Wasserstein wryly noted, “when your name is Wendy Wasserstein and you’re from New York, you are the walking embodiment of ‘too Jewish.’” Among the favorable reviews was Variety’s, which acknowledged Wasserstein as “a hawk-eyed observer of urban professional foibles [who] knows how to construct jokes.”

Wasserstein’s Pulitzer Prize–winning play, The Heidi Chronicles, was workshopped at the Seattle Repertory Theater, and then presented by Playwrights Horizons. In 1989 it moved to Broadway’s Plymouth Theater, where it won the New York Drama Critics Circle Award, the Drama Desk Award, and the Susan Blackburn Prize, in addition to the Tony. In 1995 it appeared on TNT television. The play explores the wistful character of Heidi Holland, a witty, unmarried art history professor at Columbia University approaching middle age and becoming disillusioned with the collapse of the idealism that shaped the 1960s. An episodic, seriocomic biography that spans twenty-three years, the play begins with a slide lecture in which Heidi affirms the neglect of women artists; it then skates back to a 1965 Chicago high school dance and on to college, where Heidi and her friends become ardent feminists and radicals. We see them at a 1968 Eugene McCarthy rally in New Hampshire, a 1970 Ann Arbor consciousness-raising session when Heidi is a Yale graduate student, and a 1974 protest for women artists at the Chicago Art Institute.

Heidi’s friends become swept up by the materialism and narcissism of the Reagan eighties. Heidi, however, remains adamantly committed to the ideals of feminism and feels stranded. At her high school alumni luncheon, the climax of the play, she looks around at her materialistic, married friends who chose easier or different paths and delivers a long, impromptu confession concerning her feelings of abandonment and her disappointment with her peers. “I thought the point was we were all in this together,” she exclaims. By the end of the play in 1988, Heidi adopts a daughter as a single parent, hoping that the daughter will feel the confidence and dignity that were the aims of the women’s movement.

Many feminist critics assaulted the play, insisting that Heidi “sells out” in the end by adopting a baby and that the true cause of her depression was her not having a man. While it is clear that the play is not radically feminist, it is a mistake to read the ending so literally. Wasserstein, who resisted being labeled a “feminist” playwright, arguing that men are not subject to such labels, said that Heidi adopts a baby because that choice is consistent with her character. Heidi and her daughter become icons for future generations of women who will have a stronger sense of self in a more equal society.

Wasserstein affirmed that her 1992 Broadway comedy hit, The Sisters Rosensweig, set in London at the moment of the 1989 Soviet coup, is “about being Jewish.” It dramatizes the disparate lives of three sisters, Sara, Pfeni, and Gorgeous, as they congregate to celebrate Sara’s fifty-fourth birthday. Wasserstein wanted to write a play that celebrated the possibilities of a middle-aged woman who, unlike her other protagonists, does not end up alone. In addition, each sister comes to terms with her Jewish heritage differently. Indeed, Wasserstein said that her notion of theater derived from her Jewish identity: “I think in many ways my idea of show business comes from temple; not that I really practice, but that sense of community, melancholy, and spirituality is there.” Furthermore, The Sisters Rosensweig also reflects the profound impact of Chekhov on her imagination, specifically The Three Sisters. Chekhov’s ability to capture the quotidian aspect of life as he balances humor and sorrow particularly appealed to Wasserstein. Sisters moved from the Greenwich Theatre in London to the Old Vic in the fall of 1994.

Her 1997 play, An American Daughter, presented at Lincoln Center in Manhattan, takes place in Washington and was inspired by what Wasserstein called “the blatant unfairness” of what happened to Zoe Baird, Lani Guinier, and Kimba Wood in the wake of being nominated for government office. Once the media exposes the fact that Dr. Lyssa Dent Hughes, the great-granddaughter of Ulysses S. Grant and the daughter of a conservative Republican senator, neglected to do jury duty, she is forced to resign as nominee for surgeon general. Not only does the play expose the sexism to which women are subjected in the public arena, but it is also Wasserstein’s first play to take a hard look at the problems of liberalism. The most overtly political play of her career, An American Daughter was also her first play to move directly from the Seattle Repertory Theater to Broadway. While some critics felt the play lacked direction, others thought it cleverly combined the features of a social problem play, a comedy of manners, and a political satire.

Old Money (2002) is also a comedy of manners, one that examines the theme of materialism touched on earlier in the The Heidi Chronicles. While the setting remains the same throughout, the play moves temporily from the “Gilded Era” of the early twentieth century to the present, with each character playing a role from both eras. Performed to mixed reviews at Lincoln Center in 2002 (many critics found the constant switch between epochs confusing), Old Money demonstrates the effects of money on families—and how little that has changed over the years.

Adaptations

Wasserstein also adapted the works of other writers, including Chekhov’s short story “The Man in a Case,” which examines the relationship between a stuffy classics professor and his vivacious fiancée (1985). With Christopher Durang, a friend and collaborator from the Yale days, she adapted Charles McGrath’s short story “Husbands” for the screen as The House of Husbands (1981), which comically explores gender conflict in divorced couples but ultimately celebrates the possibilities of marriage. In 1991 Wasserstein’s 1990 adaptation of the British comedy Antonia and Jane was made into a film which explores her canonical concerns of friendship and rivalry between single women with identity crises, who are frustrated in their romantic and professional lives. In 1994, with choreographer Kevin McKenzie, she adapted The Nutcracker Suite for the New York City Ballet, focusing on Clara’s coming of age. The ballet reached New York during the company’s 1994 May season at the Metropolitan Opera House.

Musicals

Wasserstein also wrote three musicals. The first was a parody about the Miss America pageant, When Dinah Shore Ruled the Earth, co-written with Durang while they were at Yale (1975). Happy Birthday, Montpelier Pa-zazz, containing the seeds of Wasserstein’s concern with frustrated relationships between men and women, opened at Playwrights Horizon in 1976. Playwrights Horizons also presented her 1985 musical, Miami, about a brother and sister coming of age as America grows out of the Red Scare of the Eisenhower fifties into the promise of liberalism in the sixties.

Television

In 1984, Wasserstein began writing comedy skits for the television series Comedy Zone. For KCET-TV in Los Angeles, she wrote “Drive,” She Said, a comedy about a woman learning to drive late in life as she struggles with her identity. Kiss, Kiss Dahlings, a 1992 teleplay for public television, humorously depicts three generations of actors, two of whom sell out to popular culture. Uncommon Women and Others, The Heidi Chronicles and An American Daughter were also adapted for television.

Essays

Wasserstein’s essays have appeared in the New Yorker, Esquire, New York Woman and Harper’s Bazaar, among others. A collection, Bachelor Girls, was published in 1991; its subjects are as diverse as the three influences that shaped her imagination in her youth—Richard Halliburton’s Complete Book of Marvels, the Helena Rubinstein Charm School, and Broadway musicals—but the unifying subject is young, unmarried women, who support themselves and often live alone. She wrote a column called “The Wendy Chronicles” in Harper’s Bazaar and began as a columnist for New Woman magazine in 1994. Shiksa Goddess (Or, How I Spent My Forties), a collection of essays written over the period of a decade, was published in 2002. Among other personal issues, the book depicts her struggles through almost ten years of fertility treatments. Wasserstein, who never married, became pregnant at the age of forty-eight; her daughter Lucy Jane was born in 1999.

Later Work and Legacy

Wasserstein made a special place for herself in the American theater by being one of the first women to stage women’s issues with the astute and comic eye of a social critic. As her characters, accomplished women who are trying to find fulfillment in their personal and professional lives, discover that it is impossible to “have it all,” they gain a better understanding of who they are. Although she resisted being labeled a “feminist” playwright, arguing that men are not subject to such labels, she was seriously troubled by the unjust inequities based on gender that she saw in American society. Therefore, her plays continued to focus on women struggling to define themselves in a “postfeminist” America that still suffered from the backlash of sexism, homophobia and traditional values but also from the problem of liberal entitlement. Her writing not only reflected her passionate interest in women but also revealed the fact that she was Jewish and a New Yorker.

Wasserstein’s later work, however, depicts men more generously than did her earlier creations. Indeed, she was quick to point out that she owed a great deal to two men who were instrumental in her career: the artistic director of Lincoln Center, Andre Bishop, the former artistic director of Playwrights Horizons, who produced her early plays; and director Dan Sullivan. While her plays continued to expose the brutal reality of sexism, they always maintained a comic, wistful, Chekhovian tone, and at the same time had an unmistakable Jewish urban quality.

Wendy Wasserstein died on January 30, 2006, after a bout with lymphoma. She was fifty-five years old.

She is featured in Making Trouble, the JWA documentary film about women comedians.

Dolan, Jill. Wendy Wasserstein. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017.

For a complete bibliography of works by and about Wendy Wasserstein, see Jan Balakian, The Dramatic World of Wendy Wasserstein (1998).

Wasserstein’s manuscripts are collected at the Mount Holyoke Archives, South Hadley, Mass.