Violence Against Women in the Hebrew Bible

The Bible contains many instances of physical, sexual, and religious violence against women in biblical narratives, legal materials and prophetic rhetoric. The most brutal cases of sexual violence in narratives are often used to indicate significant dysfunction in society. These narratives of violence also treat women as the property of men. While many legal texts protect the rights of women, there are many laws that promote violence and blame the victim. The most pernicious example of violence against women appears in a number of prophetic books in which a marriage metaphor is employed. In these texts, God is described as a faithful husband and Israel (or Jerusalem) is described as a sexually promiscuous wife who is punished by exposure, beating, and rape. Only in recent decades have feminist readers of these texts pointed to the ways in which these texts reflect and reify violence against women.

The Bible contains many occurrences of violence against women. Some instances are explicit and others are subtle. In a number of biblical narratives, female characters are beaten, raped, mutilated, and killed. While physical violence is easy to identify, psychological violence is more difficult to discern, in part because we get little information about the inner lives of biblical characters. Violence against women can also be found within the legal sections of Torah. Finally, perhaps the most insidious type of violence against women appears in the form of metaphor in prophetic literature. It is important to note that we know very little about the real life experiences of violence for ancient Israelite woman. In other words, violence against women in the Bible is a literary convention.

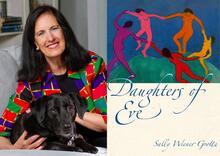

The first systematic study of violence against women in biblical narrative was Phyllis Trible’s Texts of Terror, in which she tells the stories of Hagar, the princess Tamar, the unnamed concubine of Judges, and Jephthah’s daughter without downplaying the pain and the violence of these stories. Since this groundbreaking work, a plethora of studies on violence in the Bible, and specifically violence against women, has emerged.

Sexual Violence Against Women in Biblical Narratives

The most brutal cases of sexual violence against women are often a sign of societal breakdowns and a prelude to large-scale massacres. When Dinah is raped by Shechem, the prince of the city with the same name (Genesis 34), Dinah’s brothers take the assault as a matter of family honor and use the opportunity to massacre all the inhabitants of the town. The end of the Book of Judges functions rhetorically to convince its readers that without a monarchy, society will fall into chaos. In this context, we encounter Judges 19–20, a narrative in which a host offers to throw the women of his household out into the street where a pack of men are intent on raping the male visitor. One of the women, who is never named, is gang raped, killed, and mutilated. This act leads to a civil war among the tribes of Israel. In 1 Samuel, when one of David’s sons, Amnon, rapes his half-sister Tamar, a feud among brothers ensues, and Amnon is ultimately killed by his brother Absalom (1 Samuel 13). In none of these cases does the text express any concern about the women themselves; they function as pawns in larger narratives of violence. While nobody comforts Dinah or Tamar, there is an acknowledgement that these types of behaviors should not be the norm. These are narratives of violence and strife.

Other Cases of Violence Against Women in Biblical Narratives

In other cases of violence against women, the perpetrators often view women as property. Violence against women can be perpetrated by other women, as is the case of Sarah and Hagar (Genesis 16). In the text Sarah brutalizes Hagar so severely that Hagar escapes while pregnant into the wilderness, where her chances of survival are slim. When she returns to Sarah, she must submit herself to further oppression. Sarah’s wrongdoing is never acknowledged.

In another case (Judges 21), the tribes of Israel decimate the tribe of Benjamin in a civil war. After the massacre of all of the members of the tribe (apart from the soldiers), the other tribes realize that Benjamin might not endure. In order to solve this problem, the soldiers of Israel conquer another region and massacre the population with the exception of 400 virgins, who are given to the warriors of Benjamin.

The Book of Numbers (Numbers 5) provides a jealous husband with a ritual to determine whether his wife has been unfaithful to him. No limitations are put upon the man; he may bring his wife to the priest to endure an ordeal whenever he desires. In this test, the wife is required to drink poison, and if she survives without harm to her body, she is presumed innocent. The violence in this case is not just physical but also religious, insofar as the violence is integrated into the body of a religious ritual.

Even heroes like Esther are the victims of violence. Esther was forcibly taken into the king’s harem and treated like property. Again, in these cases, violence is acceptable because the woman is treated as property.

Violence Against Women in Biblical Law

While many legal texts protect the rights of women, many laws promote violence and blame the victim. Exodus 22:18 prescribes the death penalty only for a female sorcerer, even though both men and women practiced sorcery and other forms of divination. In Deuteronomy 22:22-23, if a man rapes a married woman within a town, the woman is put to death alongside the perpetrator of the crime. She is spared only if the rape occurs out in the countryside, where she cannot call out for help. According to Exodus 21:7, Israelite female slaves are not set free after six years of service as are male slaves.

Violence Against Women in Prophetic and Wisdom Literature

The most pernicious example of violence against women appears in a number of prophetic books in which a marriage metaphor is employed. In these texts, God is described as a faithful husband and Israel (or Jerusalem) is described as a sexually promiscuous wife. Sexual promiscuity is a metaphor for the Israelite or Judean treaties with other nations and syncretistic religious practices. In all of these passages, readers are invited to sympathize with God and to support the violent discipline of his unfaithful wife. In this manner, these biblical texts have been used to condone domestic violence and to communicate to men that it is within their right to beat their wives into submission.

The domestic violence metaphor first appears in Hosea 1-3, where the prophet Hosea imagines his wife Gomer to be an adulterous woman. Hosea then takes his personal experiences and equates them with the relationship between God and Israel. God/Hosea threatens to expose the woman’s nakedness and to give her to other men to be raped and beaten.

Similar texts appear in the early sections of Jeremiah and in Ezekiel. Ezekiel 16 and 23 are especially brutal, describing the wife with unrestrained sexual freedom, which needs to be controlled by public shaming, exposure of her genitals, rape, beating, and mutilation. These horrific texts feed male sexual fantasies and have been termed by some recent commentators as “pornoprophetic” because of the way women’s bodies are objectified and sexualized.

In these texts, the destruction of the Northern Kingdom and later the Southern Kingdom, along with the destruction of Jerusalem, are viewed through the lens of rape. Infiltration of the enemy into the city, the decimation of property, and the loss of life are understood through the filter of the female body. It is possible that the actual experiences of the male population as captives of war led to a collective sense of emasculation. The prophets, especially Ezekiel, were trying to make sense of traumatic events. In order to make sense of their victimhood, they had to imagine themselves collectively as God’s wife, receiving the appropriate punishments for bad behavior that they, presumably, would inflict on their own wives. In the search for a theological rationale for their misfortunes, they may have tried to shift their experience of powerlessness and loss of control (associated with women’s social positions) to a hyper-identification with God, who has every right to inflict brutal punishment upon his wife.

Another important biblical theme is that of the personified city Zion, who plays the role of the victim of violence. The Book of Lamentations, in large part, gives voice to the personified widow of God, who laments her state of abandonment and victimhood. She blames herself for the violence done to her (Lamentations 1:8-10). Lamentations was written following the city-lament genre that was common in Mesopotamia. These balags, city-laments, were often placed into the mouth of the weeping goddess of a city. For example, the goddess Ningal laments the destruction of her city, Ur. In these laments, the female voice expresses pain and despair with exquisite detail. However, only in the biblical version of the city lament is the woman who laments the same woman who was actually subject to the violence, and who is also the woman who looks to her abusive husband for reconciliation.

Conclusions

The biblical texts reflect the attitudes and norms of ancient Near Eastern societies. We know very little about how women were treated by men in ancient Israel. Most female characters in the Bible are not victims of violence; they may not have the same access to power as men do, but they are not portrayed as victims. Female characters are often powerful actors in narratives. The most extreme cases of violence against women signify some larger dysfunction. Other cases simply seem to reflect the reality of the times in which these texts were written.

In the history of interpretation, these texts have been used to promote the idea that men have the right to use violence as a method of control over women. While the violence against women in the narrative material is explicit and easy to identify, violence through the language of metaphor is more insidious. It is easy to claim that “it’s just a metaphor,” but biblical commentators have read these texts with complete empathy for God’s (the husband’s) perspective. They build further upon these texts, describing how lucky Israel is because God does not ultimately abandon her. Only in recent decades have feminist readers of these texts pointed to the ways in which they reflect and reify violence against women. These texts suggest that women are generally the property of men, and as such, may be controlled, manipulated, and brutalized.

Anderson, Cheryl B. Women, Ideology and Violence: Critical Theory and the Construction of Gender in the Book of the Covenant and the Deuteronomic Law. London: Bloomsbury, 2004.

Dobbs-Allsopp, F.W. Weep, O Daughter Zion: A Study of the City –Lament Genre in the Hebrew Bible. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1993.

Exum, Cheryl J. “The Ethics of Biblical Violence against Women,” in The Bible in Ethics: The Second Sheffield Colloquium, eds. J. W. Rogerson, M. Davies, and M. D. Carroll R. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1995, 248–271.

Kalmanofsky Amy, ed. Sexual Violence and Sacred Texts. Oregon: 2020.

Meyers, Carol. “Rape or Remedy? Sex and Violence in Prophetic Marriage Metaphors.” In Prophetie in Israel: Beiträge des Symposiums “Das Altes Testament und die Kultur der Moderne,” anlässlich des 100. Geburtstags Gerhard von Rads [1901–1971], Heidelberg, 18.21. Oktober 2001), edited by Hugh Williamson, Konrad Schmid, and Irmtraud Fischer, 185-198. Münster: Lit-Verlag, 2003.

Muller, Ilse. “Prophetic Violence. The Marital Metaphor and its Impact on Female and Male Readers.” In Prophetie in Israel: Beiträge des Symposiums “Das Altes Testament und die Kultur der Moderne,” anlässlich des 100. Geburtstags Gerhard von Rads [1901–1971], Heidelberg, 18.21. Oktober 2001), edited by Hugh Williamson, Konrad Schmid, and Irmtraud Fischer. Münster: Lit-Verlag, 2003.

Setel, T. Drorah. “Prophets and Pornography: Female Sexual Imagery in Hosea,” in Feminist Interpretation of the Bible, ed. L. M. Russell. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1985.

Trible, Phyllis. Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives. Philadelphia: Fortress: 1984.

Weems, Renita J. Battered Love: Marriage, Sex and Violence in the Hebrew Scriptures. Minneapolis: Fortress, 1995.