In the Shoes of Biblical Women

What can Sarah and Hagar teach us about interfaith relationships? If you were Eve, would you have eaten the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden? How do you think Queen Esther felt living in the palace of King Ahasuerus, and could she have learned anything from his first wife, Vashti?

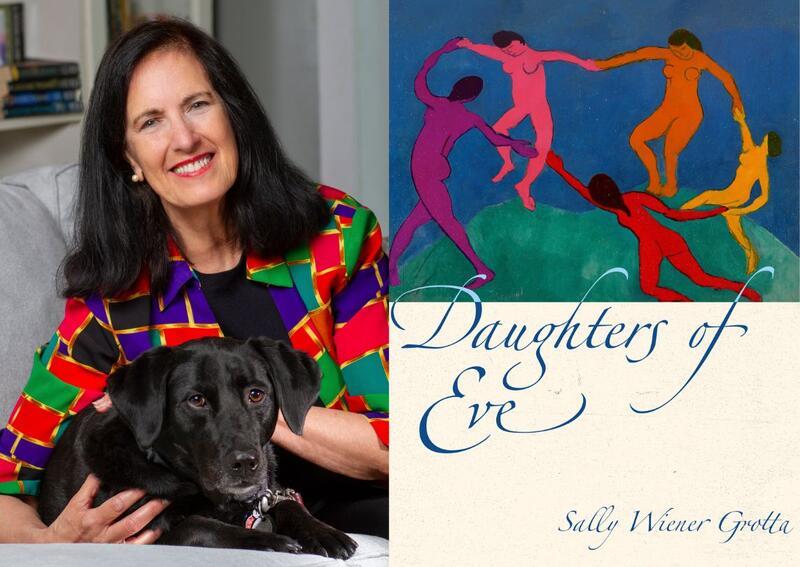

In her new book Daughters of Eve, Sally Wiener Grotta places the reader in the shoes of many of the strong women in the Torah. Each chapter focuses on a different woman, group of women, or female relationship. After a short explanation of their circumstances, Grotta dives into an examination of values. What does each woman teach us? How have these lessons played out in Grotta’s life? How do they apply to your own life?

By blending memoir with Torah study, Grotta makes each biblical figure relevant to today. After sharing her own insights and reflections, she calls on readers to reflect on their own experiences in subsequent pages. These pages are arranged like a bullet journal, inviting readers to express their thoughts and feelings on the page.

I’ve read many books with prompts that fail to probe beneath the surface of a topic, so I was skeptical at first. But to my surprise, I found myself thoughtfully challenged by the questions Grotta raised.

After telling us the story of how Eve eats from the forbidden Tree of Knowledge, leading to her and Adam to be cast out from the Garden of Eden, Grotta asks us as readers if we would have done the same as Eve. At first, I wasn’t sure. I’m incredibly curious and enjoy trying new foods (having most recently eaten cuy—guinea pig—in Ecuador). But I also don’t know if I would be brave enough to take on the burden of collective suffering that was ultimately unleashed as a result of this sin.

Thinking over the pros and cons of both choices—a life of relative ease and comfort or a life with tribulations, but also with more joys—made me realize that perhaps I would have eaten the forbidden fruit. I’ve never taken the easy path in life; instead, I’ve chosen to go my own way. In high school, I organized walkouts to support March for Our Lives, the student-led organization against gun violence, when it would have been easier to stay silent. As a graduate student in public policy, it would have been simpler to study in the US, where I’m already familiar with the academic system, wouldn’t have endured rigorous competition for funding, and wouldn’t stick out for something as basic as my accent. Instead, I chose to study in the UK, which has given me the chance to learn new policy perspectives, to live in a society that values free healthcare, and to make friends with thinkers from across the world. I even see writing for the Jewish Women’s Archive as an example of not choosing an easy path—writers never find writing easy—but rather as a challenge I choose to take for the fulfillment it provides.

The thought-provoking morsels in Daughters of Eve also allow for a deeper connection with biblical women. Consider the story of Sarah and Hagar, in which Sarah, unable to have children, forces her servant Hagar to have children for her with her husband Abraham. After Hagar becomes pregnant, Sarah treats her harshly until Hagar runs away. We might be inclined to judge Sarah for her controlling and abusive behavior. But Grotta asks readers to reconsider the story, to think about people in their own lives whom they have judged, and to reflect on the need to accept people in all their “human messiness.”

Grotta herself notes how in her relationship with Judaism, many of these female figures felt like “ancient archetypes” rather than role models and sources of wisdom. I felt the same way. Often in my own Torah study, I felt women were either judged without mercy, particularly for choices around their sexuality, or put on a pedestal as an example for other Jewish women to follow. Both choices created a distance and separation that made me feel unable to connect with them.

Grotta’s humanization and calls to empathize with the women in the Torah creates a uniquely feminist text in which readers can admit their flaws, judgments, and spiritual aspirations in a dialogue with these women, rather than in comparison to them. It allows us to understand these women—and ourselves—as rich and complex human beings.

Though I read this book alone, I agree with the author that it is probably most enriching to read as part of a group of women engaged in Torah study. While Grotta doesn’t specify an age, I see this book as a wonderful vehicle for young feminists to find their own voices alongside the voices of other strong women from the Torah.