Modesty and Sexuality in Halakhic Literature

Though it is not mentioned in the Bible, the laws of modesty in Jewish life have developed into a significant part of modern halakhic practice. Along with a set of rules for men’s behavior, the rules of modesty are designed to restrain men’s sexual urges, even as the obligations largely fall onto women. These rules are meant to ensure that sex occurs in a way the rabbis view as appropriate. In addition to these rules, the rabbis also regulate sex itself, giving men an obligation to have sex. However, opinions differ across different Jewish movements as to whether that sexuality is to be enjoyed or is merely an obligation to be performed. Modesty remains an important topic in Israeli debates about women’s role in society.

The Concept of Modesty

Modesty (Modestyzeni’ut), in its broad sense, represents a mode of moral conduct that is related to humility. A person who behaves modestly refrains from extroverted behavior that is supposed to speak of him- or herself. This expansive view also includes sexual modesty. The Bible contains only two expressions related to the root צ.נ.ע (zaddi-nun-ayin), neither of which is expressly connected with sexual modesty. The prophet Micah (6:8) provides a clear example of this expansive view of modesty: “He has told you, O man, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: only to do justice and to love goodness, and to walk modestly with your God.” The only other appearance of this root is in Proverbs (11:2): “[...] but wisdom is with the unassuming [zenu’im],” that also is understood as humbleness (“who conceal themselves out of their great humility” [Mezudat Zion]); or as referring to those who possess excellent self-discipline in their search for wisdom and who employ strict methodological rules in this quest (R. Levi ben Gershom).

The Rabbinic literature already makes extensive use of the term in its sexual connotation, albeit still not as its dominant meaning. Thus, the Rabbis find an allusion to sexual content in the statement by Micah:

R. Eleazar said: What is the meaning of what is written [Mic. 6:8]: “He has told you, O man, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: only to do justice and to love goodness, and to walk modestly with your God"? “Do justice”—this is the law [that may be deduced by human intellect]; “love goodness”—this is acts of lovingkindness; “and to walk modestly with your God”—this is attending to funerals and attending to a bride’s dowry. Can we not draw an a minori ad majus inference: if, regarding matters that are normally performed publicly, the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah enjoins “to walk modestly,” how much more so as regards matters that are usually performed in private (BT Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.Sukkah 49b).

The term “modest” is applied to people who are scrupulous in the observance of the commandments, privately and humbly. Such individuals are called “the modest” (Codification of basic Jewish Oral Law; edited and arranged by R. Judah ha-Nasi c. 200 C.E.Mishnah Ma’aser Sheni 5:6), “tznu’ei [alternately translated as “the pious,” “the more scrupulous”] of the School of Hillel” (M Demai 6:6), and the like. Women usually are categorized as “modest” in the sexual sense. Thus, the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud praises the Matriarch [Sarah], who remained in the tent during the visit by the angels to Abraham, “to inform you that the Matriarch Sarah was modest” (BT Bava Mezia 87a); Rachel, whose modesty was rewarded by having King Saul as a descendant (BT Lit. "scroll." Designation of the five scrolls of the Bible (Ruth, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The Scroll of Esther is read on Purim from a parchment scroll.Megillah 13b); Tamar, who covered her face, and was rewarded by having kings and prophets among her descendants (following BT Megillah 10b); and Ruth the Moabite, who took care to glean the sheaves in a modest manner (“she gleaned the standing sheaves standing, and the fallen, sitting” [BT SabbathShabbat 113b]; Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac; b. Troyes, France, 1040Rashi: “and she did not bend to take them, out of modesty”). By virtue of the modest behavior that Boaz saw in her, he took her for a wife.

Like “modesty,” the term derekh erez also has a dual meaning in the Rabbinic literature. In addition to representing polite and proper general social conduct, it also embodies instructions and recommendations for fitting sexual behavior (see the introduction by Michael Higger, Higger 1970: 2–3). However, while the sexual connotation came to prevail in the term zeni'ut, this meaning waned for derekh erez.

The Rabbis call immodest sexual behavior “kalut rosh” (literally, frivolity), which is the term used by the Talmud in its description of the separation of men from women that was initiated at the Simhat Beit ha-Sho’evah celebration in Jerusalem:

Our masters taught: Originally, the women used to be inside [i.e., in the Women’s Court], and the men outside, and this led to kalut rosh. It was [consequently] established that the women would sit outside and the men, inside, but this still resulted in kalut rosh. It was [then] established that the women would sit up above [in the gallery], and the men, below (BT Sukkah 51b).

The concept of “modesty” was also infused with a dual meaning in the ethical conduct literature, and especially in the The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalistic strain of this genre, with a lack of symmetry in the types of modesty primarily required of men and of women. A representative example of this is provided by the seventeenth-century Kabbalistic book of ethical conduct Shenei Luhot ha-Berit by R. Isaiah Horowitz (1560–1630). In Sha’ar ha-Otiyyot (the “Gate of Letters”), Ot צ (tzaddi), s.v. “zeni'ut,” Horowitz defines the obligation of modesty incumbent on the man as follows:

A man is to be modest in all his ways: in his food and drink, in his speech, in his walking, in his garb, and modest with his wife. As a general rule, all his actions are to be with modesty and shame, for shame is a great attribute. [...] A further great and marvelous, lofty and exalted quality that is included in the attribute of modesty—“walk modestly with your God”—is that of seclusion, that a man seclude himself and sit alone, closed up, within his four cubits of the law.

The modesty required of the woman, in contrast, is almost exclusively limited to the sexual realm:

And certainly, the woman is obligated to be exceedingly modest. All her glory shall be within, and she is to conceal herself from every man in the world in every manner possible. Her eyes shall always be cast down and her speech moderate. Not even the smallest part of her body shall be exposed, so that no man will come to sin through what he sees. [...] Her voice shall not be heard, for a woman’s voice is licentiousness. Not a one of her hairs is to be seen. The Zohar (III: 79a) placed great emphasis on this sin; and even in the most private chambers she must take care.

Sources for Laws of Modesty and their Halakhic Status

The Oral Law tradition bases all the legal restrictions pertaining to modesty, and the barriers against arayot (literally, the forbidden incestuous sexual relations; also applied in a more general sense to all forbidden behavior of a sexual nature), on Lev. 18:19: “Do not come near a woman during her period of uncleanness to uncover her nakedness,” even though the verse itself refers to a menstruant woman (Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah). A few other expositions additionally derive the general prohibition of coming near the arayot from Lev. 18:6: “None of you shall come near anyone of his own flesh to uncover nakedness”; while yet others, in the spirit of R. Pedat (and also based on this verse), reject the general prohibition. In contrast with the latter, the legal authorities among the Rabbinic authorities/halakhic decisors/ biblical commentators of the mid-11th to mid-15th c.. The period of the rishonim followed that of the geonim and preceded that of the aharonim.Rishonim (medieval authorities), including Moses ben Maimon (Rambam), b. Spain, 1138Maimonides, preferred Lev. 18:6 over 18:19, possibly because of its less specific nature. (Some of these laws were based on Deut. 23:10: “When you go out as a troop against your enemies, be on your guard against anything untoward.”)

Thus, for example, the Rabbinical exegesis (Sifra, Aharei Mot 9:13):

“Do not come near a woman during her period of uncleanness to uncover her nakedness”—this teaches only not to uncover; from whence is [the prohibition] not to come near? Scripture teaches, “Do not come near.” This teaches neither to approach nor to uncover only regarding the menstruant woman; from whence is [the prohibition] neither to approach nor to uncover, regarding all the forbidden sexual relations? Scripture teaches, “Do not come near to uncover.”

“Coming near to the forbidden sexual relations” includes all the forms of behavior that entail sexual stimulation and therefore is identical with the strictures of modesty. This exposition raises “coming near” to the status of a Torah prohibition; in contrast, the Talmud contains the dissenting opinion of R. Pedat, that all the laws of modesty are of Rabbinical origin: “This disagrees with R. Pedat, for R. Pedat said: the Torah forbade only the intimacy of the forbidden sexual relations, as it is said, ‘None of you shall come near anyone of his own flesh to uncover nakedness’” (BT Shabbat 13a).

This Talmudic disagreement concerning the status of the modesty strictures was continued by the Rishonim and is expressed in the difference of opinion between Maimonides and Nahmanides in Sefer ha-Mizvot (Prohibition 353). Maimonides (1138–1205) includes in his count of the 613 commandments the modesty strictures encompassed in “coming near” the forbidden relations (Chavel 1967: 319–320), Negative Commandment 353: Intimacy with a kinswoman. He writes:

By this prohibition we are forbidden to seek pleasure in contact with any kinswoman who is within the prohibited degrees, even though it does not go beyond such endearments as embracing, kissing and the like. The prohibition of such conduct is contained in His words (exalted be He), “None of you shall approach to any that is near of kin to him, to uncover their nakedness” [Lev. 18:6], which have the same meaning as if He had said: ‘You shall not approach them in a way which might lead to forbidden intercourse.’

In contrast, Nahmanides (1195–1270), based, inter alia, on an analysis of the Talmudic discussion in which R. Pedat’s view is presented, maintains that:

According to a study of the Talmud, it is not the case that “coming near” that does not entail the uncovering of nakedness, such as embracing and kissing, [constitutes the violation of] a [Torah] prohibition and [is punishable by] lashes. [...] We understand from them that for them this is a Rabbinical prohibition [...] and Scripture is merely a support. There are many similar instances in Sifra and Sifrei.

Following R. Pedat, Nahmanides also is of the opinion that “coming near” the forbidden relatives refers to the actual act of intercourse: According to him, the Rabbis do not disagree with R. Pedat on this point.

The second verse on which some of the modesty strictures are based is from Deuteronomy (23:10): “When you go out as a troop against your enemies, be on your guard against anything untoward.” Various expositions use this verse as a general Biblical foundation for modest and restrained behavior, including a caution against sexual stimuli. This comprehensive warning includes different prohibitions, such as that of gazing at a woman and even of looking at her clothing, as well as looking at coupling animals (BT Avodah Zarah 20a–b; in the parallels, such as Sifrei on Deuteronomy, 254:10, the exegesis of this verse is not limited to modesty in the sexual sphere. A Talmudic tradition (BT Sanhedrin 75a) relates:

A man once set his eyes upon a certain woman, and his heart was consumed by passion [thus endangering his health]. The physicians were consulted, and they said, There is no cure for him until she cohabits. The Rabbis replied: Let him die rather then she should submit to him. [Additional suggestions, and the responses by the Rabbis:] Let her stand before him naked—Let him die rather than her standing naked before him. Let her converse with him from behind a fence—Let him die rather than her conversing with him from behind a fence.

The discussion in the Talmud does not rule out the possibility of this woman being unmarried, but the lovestruck man is nevertheless barred from marrying her, so that, among other reasons that are advanced, “the daughters of Israel would not be immodest in matters of sexual intimacy.” This tradition, which teaches of the gravity of sinful thoughts and the power of the erotic urge, became a normative constitutive tradition, to this day, in many works discussing modesty.

The Jewish Approach to Sexuality and the Bounds of Modesty

The Jewish attitude to sexuality is not homogenous, but contains a broad spectrum of views, from regarding sexuality as a negative value from which one should forbear to the greatest extent possible, to viewing it in a positive light. These basic positions concerning sexuality and sexual desire influenced the practices governing modest behavior and the halakhic strictures that fashion the ethos of modesty.

The prevalent Rabbinic view is based on a dualistic conception of the two urges within man, the good inclination and the evil urge, which is mainly, but not exclusively, identified with the sexual urge (see, e.g., BT Sukkah 52a; JT Sukkah 5:2, and parallels). A Talmudic narrative in The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yoma (69b) relates that the evil inclination that incites people to engage in idolatry was annulled during the Return to Zion period, after the prayer of the returnees was answered. All that remained is the evil inclination that is identified with sexual desire, albeit of weakened intensity. There is tension between the good and evil inclinations, and it is incumbent upon man to overcome his predilection for evil by means of his proclivity for good.

In addition to this dualistic approach, the Rabbis also voice a different, unitary conception, according to which sexual desire is not intrinsically bad. It has the potential to be harmful, just as it has the potential for good. Some Rabbinic sources describe it as also essential for the existence of the world. It was not by chance that Maimonides, who tended toward sexual abstinence, in his Commentary on the Mishnah shifted the definition of the evil inclination from the sexual realm to man’s obligation to love God and believe in Him “even with wrath, anger, and ire, all of which is the evil inclination.”

Both conceptions—the prevalent dualistic view and the less common dialectic unitary perspective—were already apparent in the early Jewish literature, such as Ben Sira and the Testaments of the Twelve Tribes (see Boyarin 1993: 67–70), and they continued in the Rabbinic literature. These different conceptions of the significance and nature of human sexual desire influenced the notions of what constitutes the proper bounds of modesty.

Judaism distinguishes between obligatory duties and optional acts in the sexual relations between man and wife. The former include relations for the purpose of fulfilling the obligation to be fruitful and multiply, or to fulfill the husband’s conjugal duty (Biblically mandated fulfillment of a wife's sexual needs.onah) to his wife. Ascetic orientations sought to limit to the greatest extent possible not only sexual relations thought to be optional, but also the physical pleasures of obligatory sexual acts. Thus, for example, some Talmudic sources praise the individual who denies himself pleasure while performing the sexual act, as in the following Talmudic vignette (that would eventually become a constitutive source for the orientations favoring abstinence) featuring Imma Shalom, who praised her husband’s conduct with her:

Imma Shalom, the wife of R. Eliezer and the sister of Rabban Gamaliel, was asked: “Why are your children beautiful? During intercourse, how does [your husband] conduct himself towards you?” She replied, “[...] [During intercourse] he uncovers a handbreadth and covers a handbreadth, and it is as though he was urged on by a demon.”

(Tractate Kallah 1:10 [Rabbinowitz 1984: 50b(2)], and parallels)

Recommendations in a similar vein, to conduct sexual relations with maximal avoidance of the accompanying pleasure, were developed as general norms in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The book Ba’alei ha-Nefesh by the Provence sage R. Abraham ben David of Posqueires (Rabad, 1125–1198) was highly influential in this direction. He observes that a man who engages in relations with his wife for the sole purpose of “sating his lust with earthly pleasures is [...] distant from reward, and close to perdition”

Having the proper intent (of fulfilling the religious obligation) while engaging in sexual relations is capable of elevating the sexual act to the level of sanctity. Under Rabad’s influence, R. Jacob ben Asher (1270–1343) formulated the following general advice, which is not directed solely to exceptional individuals:

And also when he is with her, he should not think of his pleasure, but rather as a person who is repaying the debt that he owes, as regards her conjugal relations, and to fulfill the commandment of his Creator (Arba Turim, Orah Hayyim 240).

A corresponding example of a negative approach is given by R. Joseph Hayyim (Ben Ish Hai), one of the leading rabbis of Baghdad in the nineteenth century, who incorporated halakhah and Kabbalah in his legal rulings; Even as regards religiously obligatory marital relations, R. Joseph Hayyim advises the couple to refrain to the greatest extent possible from foreplay, which he defines as “hideousness.” Needless to say, only participation by the male is the subject of discussion. The woman’s cravings and desires are not on the agenda, except, of course, for her basic right to onah. Ascetic ideals, that are fed from R. Joseph Hayyim’s demonic worldview, are incorporated in the very sexual act.

Significantly, the praise for maximal avoidance of pleasure while engaging in the sexual act is reserved solely for the husband, and not the wife. She is permitted, and entitled, to demand that her husband engage in relations with her while she is completely nude, and to fully experience physical pleasure. No known source praises women for abstention or limiting their sexual enjoyment.

Modesty and Sexuality in Mysticism, Kabbalah, and Philosophy

In contrast with this puritanical view, Sefer Hasidim (ed. Margaliot 1970: para. 509) finds nothing wrong in engaging in relations in order to delight the husband: “The other nights he shall do as is his pleasure, so that he shall not think of other women, provided that this is the wife’s wish.” Indeed, many sources view the sexual realm as a whole in a positive light, provided that the bounds imposed by the halakhah are not exceeded.

The realm of the sexual occupies an extremely important place in Kabbalistic worldviews, including those of Kabbalistic ethical conduct and A member of the hasidic movement, founded in the first half of the 18th century by Israel ben Eliezer Ba'al Shem Tov.Hasidism. It should be noted, however, that these Kabbalistic conceptions, too, are divergent, with negative evaluations of sexuality alongside more positive notions. The Kabbalistic views did not delineate new directions, but rather intensified and deepened the varying existing orientations.

Hasidism has always been conscious of the resemblance between the sexual experience and ecstatic adherence (devekut) to God. Such a positive approach to the sexual sphere, based on Hasidic mystical views, appears in the writings of R. Isaac Judah Jehiel of Komarno (1806–1874), who maintained that the sexual act can be transformed into a religious experience by force of the man’s proper intent while engaging in relations. During this transformation, which is situated within the man’s soul, the passion of the evil inclination becomes a “holy fire.”

Thus, the very act of coupling is transformed into a ritual, in the process justifying itself and imparting self-value, and the commandments of reproduction or onah are no longer needed for such self-justification.

Religious philosophy’s contribution to the diverse range of views regarding the realm of the sexual is primarily focused upon restraint and moderation. The outstanding representative of this position is Maimonides, who considered the sexual experience to be a disturbing element that prevents the attainment of the adherence of man’s thought to the divine intellects. Consequently, his differential demand for restraint, which is directed more to the scholarly than the masses In the Guide of the Perplexed (3:49; Pines 1964: 606, 609) he suggests the weakening of the sexual urge as a reason for the commandment of circumcision.

Three models may be proposed for the connection between the sexual and religious experiences. One places the sexual experience in total opposition to the religious. Kabbalists who adopt this model regard the sexual experience as one of impurity, in contrast with the knowledge of sanctity; philosophers who subscribe to this regard the sexual experience as a disturbing element, as a barrier on the path to the holy.

The second model considers sexual desire as a simulation of the experience of religious devotion, as a source of inspiration for the esteem to be afforded the intensity and nature of such devotion. Elijah de Vidas [Safed, 1545–1582], for example, states outright in his book Reshit Hokhmah, Sha’ar ha-Ahavah [the Gate of Love], chap. 4, in the name of R. Isaac of Acco, that “whoever does not desire a woman is comparable to a donkey, and even inferior to it. The reason is that the one who becomes excited [from the sexual act] must have a sense of divine worship.”

The third model regards the sexual experience as a symbolization that results in a transformation directed toward the experience of religious devotion:

By his seeing this [worldly] Rachel, Jacob cleaved to the heavenly Rachel, for all of the worldly Rachel’s beauty came from the heavenly one. [...] Man is not permitted to cleave to this worldly beauty. If, however, he is suddenly confronted by it, he must adhere by means of this beauty to the beauty of the upper spheres” (Maggid of Mezhirech, Maggid Devarav le-Ya’akov, 29–30).

These three different models appear in the world of Torah scholars who engage in study while experiencing the love of the Torah; in the world of philosophers, who “are absorbed in the love of the Lord” and are immersed in the attainment of the divine truths; and in the world of Kabbalists who seek the experience of adherence to God.

Various normative directives were derived from these positions, which were also the foundation for the fashioning of different general ethics of social conduct in the sexual realm, from the positive views that afforded full legitimacy to sexual gratification (within the accepted halakhic bounds) to the negative opinions that advocate self-restraint or even asceticism. These divergent positions are to be found in various circles, in the ethical conduct, Kabbalistic and Hasidic literatures

The Different Images of Man and Woman and the Consequent Imposition of Modesty Strictures

The limitations of modesty imposed on the woman are different from those incumbent upon the male. These distinctions ensue, inter alia, from disparate conceptions of the qualities of the woman, that were contrasted with male characteristics; the features attributed by Jewish tradition to the female were used to justify the limitations of modesty imposed upon them. It should be noted that the female image formulated below will necessarily be partial and not balanced. The traditional Jewish feminine image in antiquity and in the medieval period was based not only on Scripture and its interpretive tradition, but also on the scientific theories of those periods (see Barkai 1987; idem, 1995), which are responsible for the similar image of women in the Jewish, Islamic, and Christian cultures.

The Female Image

According to A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash Rabbah, God already took the proper steps at the creation of the woman so that she would be inherently modest, but to no avail.

When the woman was seduced by the serpent, she acquired the quality of seduction. Consequently, women effortlessly seduce men, and may themselves be easily seduced, and their modesty must be scrupulously maintained.

The apprehensions concerning women and their sexuality intensified in the medieval period. Rabbenu Bahya ben Asher (died ca. 1340) developed the thought set forth in the Midrash: “The serpent is in close proximity [in the Torah] to the woman, because Satan was created together with her, she is the embodiment of the evil inclination, and she is easily tempted” (commentary on the Torah, Gen. 3:1). The woman’s sexual appetite is great; she possesses demonic powers, by means of which she tempts males, and even places their lives in danger.

The Midrash (Num. Rabbah [ed. Vilna], para. 9) also asks: “How is she more bitter than death? Because she causes him anguish in this world, for his going astray after her; and in the end, she brings him down to Gehinnom.” According to Rabbenu Jonah ben Abraham Gerondi (1180–1263), in his commentary on M Avot 1:5, the female power of seduction is a danger greater than that of death.

The woman’s demonic power is especially great during her menstrual period—a notion that intensified the severity of the measures to be taken to keep one’s distance from a woman in this condition Based on these popular notions, menstruant women imposed various stringencies on themselves that exceeded the demands of the halakhah. R. Meir ha-Priests; descendants of Aaron, brother of Moses, who were given the right and obligation to perform the Temple services.Kohen of Rothenburg, the author of Haggahot Maimuniyyot, attests that “women would be stringent with themselves and seclude themselves during their menstrual period; they would not enter the synagogue, and even when praying, they would not stand before their fellow women.”

Many sources link women with sorcery, a tie that intensified after the Zohar connected this black art with the uncleanness that the serpent imparted to the woman in the Garden of Eden. In consequence, sorcery became an essentially female trait that is not dependent upon changeable educational, social or environmental factors. This image amplified the obligation to keep one’s distance from women, and women were burdened with a series of restrictions and requirements imposed by vow so that they would not cause men to sin.

The variegated notions of family structure and the woman’s significance and defined role in the family unit also influenced the regulations governing modest behavior. Conceptions of feminine attributes and God’s intent in creating woman aided in defining her place and in establishing the clear gender division of roles in the family many traditional commentators based their definition of the status of the woman in the family on the verse “but for Adam no fitting helper was found” [Gen. 2:20]). These conceptions were still used by Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook in the twentieth century as part of his argumentation for denying women the right to vote; he went so far as to define female suffrage as opposed to “the law of Moses and Jewish practice [dat Moshe ve-Yehudit; see below]” (see Friedman 1967: 167; Hirschensohn 1919: vol. 2, 206–209; Zohar 2003: 208–223; Cohen 1989: 51–62). At the height of the women’s suffrage controversy in Erez Israel, Rabbi Kook wrote in 1920:

The family is for us the foundation of the nation [...] the accepted view is that she must go forth, specifically, from the house, from the perfection of her family [i.e., as an integral unit], and the husband, the head of the family, who is to represent the family position, is compelled to send her forth to the public domain (see Kook, Iggerot ha-Re’ayah: vol. 4, 50).

In an unpublished letter to his family in 1927 he wrote: “‘A woman of valor’ is exempt from this entire catastrophe. She was created to ‘oversee the activities of her household.’”

The bounds of modesty were also influenced by the part played by women in earning the family’s livelihood. In medieval Europe, large numbers of women engaged in varied areas of economic activity to augment the family livelihood, more than in Spain and the Islamic lands.

The absorption and internalization by halakhic authorities in recent generations of modern egalitarian and nonhierarchical gender conceptions resulted in a different reading and renewed interpretation of the bounds of modesty. These positions find prominent expression in the writings of the rabbis Ben-Zion Meir Ouziel and Hayyim Hirschensohn, who did not regard women’s participation in public activity or their holding of public positions as exceeding the bounds of modesty.

The Requirements for Female Modesty

Modest behavior in the sexual realm is mandatory for both the male and the female. In practice, such requirements are imposed primarily upon women, and not only in their appearance in public, but also within their homes and in their sexual conduct; maintaining such standards is praiseworthy: “This is a fine attribute among women, that they do not vocalize their demands for sexual gratification” (Midrash Sekhel Tov, ed. Buber, Gen. 30). R. Hisda ordered his daughters to be modest in their home, along with their obligation to honor their husbands: “Be modest before your husbands, do not eat bread before them, and do not evacuate in the place where your husbands evacuate” (following BT Shabbat 140b).

The Rabbinic literature divides the modesty strictures imposed upon the woman into those defined as “dat Yehudit [Jewish practice]” and those categorized as “dat Moshe [the law of Moses].” The regulations belonging to the first category are more severe than the latter, and a women who violates them is liable to be divorced by her husband and lose her rights.

“It is obligatory” to divorce such a woman (Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Gerushin [Divorce Laws] 10:22), even against her will, because the regulation enacted by Rabbenu Gershom that a woman may not be divorced without her consent does not apply in such a severe case. There is a lack of symmetry between the husband and the wife on this point. If the husband does not act with the proper modesty, some Halachic decisorposkim (decisors of halakhah) are of the opinion that parallel sanctions should not be applied against him.

In practice, there was no unanimity among the legal authorities over the ages as to what constitutes the bounds of modesty. A considerable degree of divergence was to be found in the social norms in this realm, which were significantly influenced by social, economic, and geographic differences. Thus, the strictures were not fully observed in every place and in every time. Oftentimes the public was reproached to change its behavior in these realms, while in other instances the poskim justified such behavior, either after the fact or a priori.

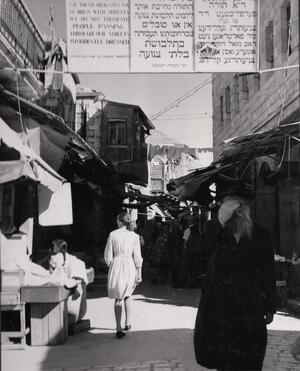

The regulations directed to the woman included as complete a covering of her body as possible, coupled with directives meant to conceal the woman and exclude her, either before or after the fact, from excessive involvement in male society. These restrictions were supported by the expositions of various verses that served as codes that guided the fashioning of the proper social ethos. A central element of this type was the appellation “ervah” (licentiousness, nakedness, sexual enticement, and the like) that Amoraitic dicta attached to certain parts of the female body, such as “A handbreadth [exposed] in a woman is ervah,” “A woman’s leg [exposed] is ervah,” “A woman’s voice constitutes ervah,” or “A woman’s hair is ervah.” Rules governing woman’s modest public garb were derived from the “handbreadth” and the “woman’s leg,” as were regulations for men, such as the prohibition of gazing at women. The mention of a “woman’s voice” resulted in the prohibition of listening to a woman singing; based on this, some even prohibit listening to prolonged speaking by a woman, such as reading the The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.hagaddah before men on the A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder night, or even teaching Torah before men. The mention of “a woman’s hair” resulted in many halakhic inquiries concerning the manner in which a married woman’s hair is to be covered. There is a very extensive halakhic literature, dating especially from the beginning of the nineteenth century, that discusses female clothing and hair styles in the modern world. These authoritative codes provided the verbal articulation that was a precondition for the public supervision of women’s behavior, while expressing the constant tension with clothing styles and social conventions concerning women’s involvement in the non-Jewish society in which Jews lived.

The verse “All glorious is the king’s daughter within the palace” (Ps. 45:14), which was taken out of its Biblical context, also served as an authoritative code for removing women from the public sphere in a long series of activities, albeit while flattering the gender-specific “glory” (or honor) of the woman, who was compared to the “king’s daughter.” The shifting applications of this concept in Jewish society were in a state of constant tension with the changing interpretation that derived from this verse the norms of proper conduct and practice. Thus, it was used to restrict women’s leaving their house to prevent their going forth to the marketplace “as village peddlers to profit”; and even to prevent women from going to the rabbinical court. This rationale was also used to prevent women from reading the Book of Esther, and even only to women.

The verse was frequently cited in the major public controversy concerning women’s suffrage that erupted within the Jewish community in Palestine in the early twentieth century. Even after this question had been resolved and women had been granted the vote, the verse still continued to be a proof-text for restricting women’s involvement in political activity or for preventing women from holding public office. Following the establishment of the State of Israel, the verse was employed to forbid the induction of women into the IDF and even to prevent their volunteering for National Service.

Discussions of the prohibition “A woman must not put on man’s apparel, nor shall a man wear women’s clothing” (Deut. 22:5) also found their way into the question of the institutionalized supervision of clothing styles to ensure modesty and continue to the present. As early as the seventeenth century attempts were made to limit this prohibition to instances in which the intent was to obscure the differences between the sexes, or for adulterous ends. As this was formulated by R. Joel Sirkes (Bayit Hadash on Tur, Yoreh Deah 182, and other sources following his lead): “But if they are worn as protection against the summer sun, or in the rainy season against the rain, there is no prohibition.” Other authorities opposed any flexibility in the interpretation of this ban and severed it from any connection with social and historical contexts. According to this view, the differences between the sexes are essential, profound, and eternal; their blurring is likely to harm societal morality.

The degree of inherent adaptability in the bounds of modesty, based on the perception of their dependence upon social and circumstantial context, is the subject of controversy regarding almost all of these strictures. A patently flexible position in this vein was adopted by R. Yom Tov ben Abraham Ishbili (Ritba, 1250–1320, one of the leading Spanish authorities), who wrote at the end of his novellae on Kiddushin (folio 81b) that:

Everything is in accordance with one’s God-fearing opinion, and this is also the law, that all is in accordance with what a person is cognizant about himself: if it is fitting for him to distance his [evil] intention, then he prohibits even gazing upon a woman’s colorful garments. [...] And if, according to his self-awareness, his [evil] inclination is compliant and submissive to him, and does not raise any stimuli, he may gaze upon and talk with [an otherwise] sexual object [ha-ervah] and greet a married woman.

Ishbili proposes a degree of personal flexibility in the enforcement of the bounds of modesty. Many authorities after him questioned the ability of people to gauge their capacity to contend with sexual stimuli. Yet another view proposes a different criterion for loosening the bounds of modesty. This public-general yardstick is the principle of “regilut,” that is, routine. In his book Arukh ha-Shulhan (Orah Hayyim 75:7), R. Jehiel Michael Epstein (1824–1908) permitted “praying and reciting blessings in front of [married women] with uncovered hair, since the majority do so at present, and this is like the [usually] uncovered parts of her body.” He based this ruling on R. Eliezer ben Joel of Bonn (Ravyah, 1140–1225, one of the leading early Ashkenazic authorities), who suggested relying upon what is commonplace.

Such reasoning also led the author of the Levushim, R. Mordecai Jaffe (one of the leading sages of Poland, died 1612), to oppose the assertion in Sefer Hasidim that the blessing recited after the wedding meal, “in whose dwelling is joy,” is not to be recited in a place where men and women see one another (see below):

Possibly because now women are very commonly among men, sinful thoughts are not so [likely to be aroused], for they seem to one as white geese, for they are so customarily among us, and since they [men] are used [to this], they pay no heed.

The latter part of this passage alludes to BT Berakhot 20a, in which R. Gidal saw no reason not to sit at the gate of the ritual bath and did not fear the evil inclination, since the women were to him as white geese. Such a relative position has been the subject of controversy from the medieval period to the present, and other poskim (halakhic decisors insisted upon the obligatory formal nature of the modesty strictures fully elaborated by the Rabbis.

In the modern reality in which women are integrated in all spheres of life, the principle of regilut is once again used by the decisors of Jewish law who are cognizant of, and accept, current social changes and accordingly adapt the bounds of modesty. The formal strictures and definitions of ervah were reexamined, based on the estimated intensity in contemporary society of these erotic stimuli. Thus, for example, R. Ben-Zion Meir Ouziel defended female participation in public activity and opposed the exclusion of women on grounds of modesty.

R. Shaul Yisraeli (1909–1995), although opposing military service by women, nonetheless refused to use this line of reasoning in order to completely forbid the induction of women into the IDF.

R. Ovadiah Yosef permitted women to recite the Ha-Gomel blessing (“Who bestows kindness,” recited after emerging from danger) in the presence of a quorum of ten men.

R. Solomon Zalman Auerbach (1910–1995) similarly abrogated the prohibition of a man walking behind a woman.

The Requirements of Male Modesty

The prevalent (although not universal) assumption underlying the strictures incumbent upon men is that the male sexual urge is greater than that of women. R. Ovadiah Yosef states outright: “Women do not possess [such] feelings”; hence, “We need not be as stringent regarding the woman, in relation to the man” (see the discussion by Yosef, Yabi’a Omer, vol. 1, Orah Hayyim 6:5). This lack of symmetry also arises from the wording of Maimonides in his Commentary on the Mishnah on Sukkah 5:2:

“At the conclusion of the first day of the Festival, they would go down to the Court of the Women”—this was a great corrective measure, that is to say, it was highly beneficial. This consisted of establishing a place for the men and one for the women. The place of the women was higher than that of the men, so that the latter would not gaze upon the women.

The architectural guidelines for the construction of the women’s section in synagogues are founded on this assumption, mainly to prevent men from looking at women, and not the opposite.

Sinful Thoughts

One of the most challenging obligations incumbent upon men is the prohibition of engaging in sinful thoughts, and the severity of the formulations of this requirement can hardly be overstated. More than any other factor, these strictures contributed to the fashioning of the ethos of proper conduct in many Jewish communities, on the one hand, and to the intensification of guilt feelings and a pervading sense of the presence of the “Evil Inclination,” on the other. One indicator of this phenomenon is the text of the Vidui (confessional prayer) recited during the The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur prayers, which specifically mentions the sin of “innermost thoughts.” The consequences of such sinful thoughts also are singled out: “shemirat ha-berit” (literally, “guarding the covenant [of circumcision],” referring to masturbation) or “shemirat ha-Yesod” (guarding the Kabbalistic Sefirah of Yesod, that is parallel to the male member) is an extremely popular subject in many books of ethical instruction.

The ban against such thoughts is exceptional in comparison with other prohibitions, that apply only to acts, and not to mental activity. Although the Rabbis were cognizant of these difficulties, they did not ameliorate the severity of such transgressions, which are among the three sins “which no man escapes for a single day” (BT Bava Batra 164b).

Various formulations further heighten the gravity of such thoughts: “Sinful thoughts are more difficult than the sin itself” (BT Yoma 29a), on which Rashi comments: “‘Sinful thoughts’—the desire for women; it is more difficult to deny one’s own flesh than the actual act.” Such lustful thoughts trouble man his entire life; as R. Ovadiah Yosef explains the current dilemma:

At present, most people who marry are more than twenty years of age. It is well-known that the Rabbis wrote [BT Kiddushin 29b] that if a man is twenty years old and has not yet taken a wife, he will spend his entire life in sinful thoughts (Yabia Omer, vol. 2, Even ha-Ezer 7:15 [s.v. “Ve-Nosaf”]).

Sinful thoughts result in nocturnal emission or masturbation:

Our masters taught: “Be on your guard against anything untoward” [Deut. 23:10]—so that a person should not engage in sinful thought by day and come to impurity by night” (BT Avodah Zarah 20b; Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.Ketubot 46a).

As this fear was expressed by R. Yosef:

And they will come to the spilling of one’s seed. This is certainly so for young men, whose vigor is with them, and by their being bested by their urge, they are expected and liable to violate the prohibition of [relations with] a menstruant woman, Heaven forbid. They will proceed from one evil to another, especially since at present licentiousness is very great, by our numerous sins (Yabia Omer, vol. 3, Yoreh De’ah 11).

R. Joseph Caro concluded from this Talmudic dictum that it is forbidden, by Torah law, to have thoughts of a woman, even an unmarried one, and thinking of an unmarried woman is more severe than contact with her. This is so because the one who has such thoughts transgresses a Torah prohibition, as it is said [Deut. 23:10]: “Be on your guard against anything untoward,” which the Rabbis, of blessed memory, interpreted [BT Avodah Zarah 20b] as meaning: that a person should not engage in sinful thought by day and come to impurity by night (Beit Yosef, Even ha-Ezer 21:1).

Maimonides maintains that sinful thoughts that engage a person’s reasoning and imagination hinder his attainment of spiritual elevation. Consequently, his demand to limit the satisfaction of sexual needs to the necessary minimum is directed primarily to Torah scholars and philosophers.

Sinful thoughts have the power to fashion social behavioral norms, and not only the conduct of the individual person. Accordingly, various instructions and prohibitions have been prescribed for modest deportment in society, such as the directive that “Husband and wife are not allowed to flaunt their love for each other [...] in the presence of others, so that the lookers-on might not come to sinful thoughts” (Kizur Shulhan Arukh 152:11; Goldin 1961, vol. 4: 20). Since sinful thoughts will probably be present in mixed company, in wedding celebrations in which “women sit among the men, where there are sinful thoughts, reciting the ‘in whose dwelling is this celebration’ blessing is inconceivable” (Sefer Hasidim, para. 393). An opposing view is held by R. Ovadiah Yosef (She’eilot u-Teshuvot Yabi’a Omer, vol. 1, Orah Hayyim, para. 6), who permits this in contemporary society, on the grounds of regilut.

Sinful thoughts are also given as the rationale for a series of prohibitions intended to protect a man from finding himself in situations likely to arouse such thoughts.

“So That Impurity Will Not Result”

The severity of engaging in sinful thoughts is usually explained by the fear that they will cause the wasteful emission of semen, either by nocturnal emission or by masturbation. The Talmudic prohibition of such emission of semen intensified over the course of time, and took on mythical and cosmic dimensions. Emission of semen has been the subject of ramified mythical development, more than any other topic in the broad and complex realm of Eros. A comprehensive monograph on this subject was written by Meir Benayahu (1985) in the context of the customary Jerusalemite prohibition of the deceased’s sons participating in their father’s funeral. The Kabbalah, and especially the Zohar, assign paramount importance to the sanctity of the semen, going so far as to claim that it was responsible for the world losing its pristine status; and that the world cannot be perfected until this sin is corrected. The midrashic legend of the spirits, demons, and human afflictions that were created by Adam during the one hundred and thirty years in which he was abstinent from Eve was developed to an outstanding degree by the Zohar, which includes in this “sin” nocturnal emissions, that are against one’s will and detrimental to the sufferer. The Kabbalists of Safed added their own excesses, asserting that “the sin and flaw of the covenant is the cause of the four Exiles [...] and as long as Israel does not repent for the [sin relating to] the holy covenant, they shall not be redeemed” and that “the iniquity of nocturnal emission extends the Exile.” Benayahu, who studied many sources that discuss this issue, notes the fact, which he finds puzzling, that additional exaggerations and severities were added in the last decades of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century.

Ways of Contending with Sinful Thoughts

Due to the scope and severity of sinful thoughts, numerous strategies for their avoidance have been proposed. The most common recommendation advises intensive and continual Torah study. “R. Simeon ben Yohai said: Sinful thoughts are lifted from anyone who has Torah teachings in mind” (Seder Eliyahu Zuta 16, s.v. “Ve-Od Davar Aher"; ed. Friedmann, “Pirkei Derekh Erez, 2); “If you encounter this corruption, drag it to the study hall” (BT Sukkah 52b and parallels). The Holy One, blessed be He, who created the evil inclination, also “created the Torah as its antidote” (BT Bava Batra 16a), “that cancels sinful thoughts” (Rashi ad loc.). R. Yom Tov ben Abraham Ishbili (Hiddushei Ritba on The widow of a childless man whose brother (yavam or levir) is obligated to marry her to perpetuate the brother's name (Deut. 25:5Yevamot, 103b) argues that this is why the evil inclination is weaker among Israel than among other peoples. As Maimonides states simply: “The thought of arayot increases only in a mind that is lacking in wisdom” (Mishneh Torah, Hil. Isurei Bi’ah [Laws of Forbidden Sexual Relationships] 22:21).

Another popular counsel calls for drastically lowering the marriageable age for men (cf. BT Yevamot 62b; Tur, Even ha-Ezer 1; R. Moses Isserles, gloss on Shulhan Arukh, Even ha-Ezer 1:1; Meiri, Beit ha-Behirah on Kiddushin 29b; see Grossman 2002: 270; Schremer 2003; idem 1996). The recommendations range between the ages of fourteen and twenty: R. Menahem Meiri (Provence, 1249–1306) prescribes: “The main time for this is from fourteen up [...] in any event, anyone who has reached the age of twenty without marrying will not be saved his entire life from the [sinful] thoughts in which he persists, unless he is one of the few” (Beit ha-Behirah, loc. cit.). For this reason, R. Hisda adds his voice (BT Kiddushin 29b) to those calling for early marriage. Maimonides (Mishneh Torah, Hil. Ishut 15:2) advises marriage between the ages of seventeen and twenty, unless a person “was engaged in Torah study and is occupied in this.” R. Ovadiah Yosef (Yabi’a Omer, vol, 2, para. 7) counsels disregarding certain instructions in Sefer Hasidim if they would result in postponement of marriage.

The recommendation that a man not remain without a woman, in order to be saved from thoughts of sin, is so strong that it justifies the permission granted by one hundred rabbis to marry a second wife if the first is hospitalized for insanity and is incapable of receiving a writ of divorce (R. Hayyim Ozer Grodzinski, Ahiezer responsa, vol. 1, para. 10; cf. Yosef, She’eilot u-Teshuvot Yabi’a Omer, vol. 8, Even ha-Ezer 1).

This reason motivates R. Ovadiah Yosef not to accept certain severities regarding menstruation (such as observing a celibate period of forty days after the birth of a son and eighty days after the birth of a daughter) since they place the husband in great danger of entertaining sinful thoughts (Yabi’a Omer, vol. 4, Yoreh Deah, para. 11:3).

Kabbalistic and Hasidic books of ethical instruction are replete with various suggestions to avoid sinful thoughts, including the adoption of subliminal processes, such as the recommendation advanced in Hasidic works that:

If you suddenly happen to see a beautiful woman, think to yourself: “Whence is her beauty? If she were dead she would no longer look this way; thus where does her [beauty] come from? Perforce it must be said to come from the Divine force diffused within her. It gives her the quality of beauty and redness [i.e., puts color in her cheeks]. The root of beauty, therefore, is in the Divine force. Why, then, should I be drawn after a mere part? I am better off in attaching myself to ‘the root and core of all worlds’ [Zohar 1:11B] where all forms of beauty are to be found (Zava’at ha-Rivash: para. 90, p. 81).

Zava’at ha-Rivash was influenced by the popular book by R. Elijah de Vidas (Safed, sixteenth century), Reshit Hokhmah (Shaar ha-Ahavah, chap. 4), which was based on a tradition from the thirteenth-century Kabbalist R. Isaac of Acco. Such techniques are frequently set forth in the ethical teachings and Hasidic literatures.

Additional Modesty Strictures “On Account of Ervah”

Some limitations were imposed on men to prevent sinful thoughts, or sexual transgressions themselves. These include the group of prohibitions connected with the concept of “ervah,”, such as the ban on hearing a woman singing. Some halakhic authorities go so far as to forbid listening to a recording of such singing, even if the singer herself is no longer alive. The woman’s voice, which is defined as “sexually enticing,” is capable of arousing sinful thoughts in the male listener’s imagination, which affect him even when there is no possibility of their realization.

This is also the basis of the prohibition of looking at women, which originates in a Talmudic maxim: “Whoever looks at women will eventually come to sin” (BT Nedarim 20a). The ban has been discussed extensively in the literature of the poskim and the ethical teachings literature, even though it was honored mainly in societies in which there is no feminine public presence, or by individuals who particularly adopted ascetic practices. In Beit Yosef R. Joseph Caro cites extremely stringent views concerning looking at women, which regard gazing upon married women as falling under a Torah prohibition, and paying such attention to unmarried women as forbidden “mi-divrei kabbalah.” The prohibition of looking is also at the basis of the edict “a man should not walk on the road behind a woman [...] if she happened to be [before him] on a bridge, he should leave her on the side [and pass before her—Rashi]” (BT Eruvin 18b, and parallels).

In contemporary society, when the public presence of women is unavoidable the onus of maintaining the prohibition has primarily been transferred to women themselves, in the demand that they properly cover their bodies, as in R. Ovadiah Yosef’s explanation of the ban on wearing short skirts (Yabi’a Omer, vol. 6, Yoreh Deah, para. 14:1). Men are asked to refrain from reading the Shema in the presence of a woman who has a single handbreadth exposed.

The prohibition against men conversing excessively with women (“which will ultimately result in adultery”—BT Nedarim 20a) is liable to result in the sweeping banishment of women from social and public activity. Leading contemporary poskim tempered this prohibition by limiting it to situations that we patently fear may deteriorate to the commission of an actual sin.

An additional modesty prohibition is that of coming into physical contact with a woman. The rabbis inordinately stress the importance of the ban: “Hence the Rabbis declared: Whoever touches a woman’s little finger is as though he touched ‘that place’ [i.e., the vulva]” (Kallah 1:7 [Rabbinowitz 1984: 50b[(2)], and parallels). Decisors from among the Rabbinic authorities/halakhic decisors/biblical commentators who were active after the rishonim, beginning in the mid-16th c.Ahronim (later authorities) disagree regarding touching and are not of one mind even regarding embracing and kissing that are not in “an endearing manner.” ShaKh (R. Shabbetai ben Meir ha-Kohen, Lithuania, 1621–1662) maintained that “even Maimonides only prohibited when one embraces and kisses in a manner of sexual endearment, for we have found in the Talmud in several places that the Amoraim would embrace and kiss their daughters and their sisters” (Siftei Kohen, Yoreh De’ah 157:10). R. Moses Feinstein, a leading American posek, permitted using public transport in New York, even though “it is difficult to prevent touching and bumping against women,” for the reason that “this is not a lustful and endearing manner,” and therefore does not entail “even a Rabbinical prohibition” (Iggerot Moshe, Even ha-Ezer, vol. 2, para. 14). Contemporary poskim who seek to intensify gender separation tend to excessively stress the severity of this prohibition, to include it in the category of prohibitions connected with menstrual impurity, and thereby magnify the severity of the ban on mixed dancing.

Dancing was conducted in various Jewish communities in medieval Europe. A noteworthy phenomenon was the institutionalization of dancing in Ashkenazic communities; special public buildings were erected for this purpose. The earliest testimony to the construction of such a building is from the late thirteenth century (1290), in the community of Augsburg (see Friedhaber 1984: 94). Many communities possessed dance houses, and some localities even engaged in mixed dancing, under the supervision and partial limitation of communal regulations; this activity was under the guidance and with the approval of the communal rabbis and sages.

Mixed dancing was the subject of fierce controversies over the course of time. These disputes included repeated attempts by rabbis and preachers to ban such activity, since they regarded it as containing most of the elements forbidden by the laws of modesty: sinful thoughts, gazing upon women, physical contact, and hearing a woman’s voice. Especially instructive in this context are the autobiographical descriptions by R. Joseph Steinhardt in 1777 (Furth, Germany) of his unsuccessful struggles to end mixed dancing (She’eilot u-Teshuvot Zikhron Yosef, para. 17). In the first half of the twentieth century, the religious Zionist youth groups and the religious kibbutzim movement engaged in mixed horah dancing; however, during the second half of the century the voices calling for a ban of mixed dancing increased, leading to a reduction of the phenomenon among Orthodox Jews. In contrast, see the critique by R. Yehudah Henkin of the excessive importance of the ban on mixed dancing, based on She’eilot u-Teshuvot Benei Banim, vol. 1, para. 37.

The Yihud Prohibitions

Halakhic literature extensively discusses the yihud prohibitions, under which, in certain conditions, a man may not be alone with his wife. These strictures, which have no Scriptural basis, are described in the Talmud as a series of decrees that developed in stages: “The Biblical prohibition of yihud refers to a married woman; David came and extended this to also include yihud with an unmarried woman; the disciples of the Schools of Shammai and Hillel came and extended this to also include yihud with a pagan woman” (BT Avodah Zarah 36b). Most of the yihud prohibitions are included in a single Talmudic discussion at the end of the tractate of Kiddushin. Intended to introduce moderating behavioral norms with the aim of preventing sin, these strictures include the prohibition of a bachelor teaching small children, to forestall situations in which the teacher would be alone with any of his pupils’ mothers.

The laws of yihud are a contemporary concern in many everyday contexts, such as situations in which a physician is alone with a patient, a male teacher with a female student, a man and a woman together in an automobile, joint use of an elevator and many similar settings.

The Bounds of Modesty: Between Halakhah and Reality

The diverse reality of social life in the Jewish world includes both ascetic and ecstatic trends, on the one hand, and a (relatively) lively social life, on the other. The full story of the complex and dynamic social life of the different communities over the course of Jewish history cannot be understood only by reading the halakhic literature and the collections of Jewish customs. The rules governing modesty and proper sexual conduct that were set forth and discussed in the halakhic literature are the normative regulations that confronted the social reality, which at times subjected itself to these guidelines, while in other instances quietly putting them aside. These strictures exhibited a greater degree of flexibility when they were understood as being dependent, in part or in full, upon the social and environmental context.

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, this degree of flexibility generally waned in ultra-Orthodox circles, usually in response to a certain erosion in sexual morals under the influence of Western culture and the Jewish Enlightenment; European movement during the 1770sHaskalah. In light of the increasingly prevalent manifestations of sexual permissiveness in all aspects of public life, this trend intensified, beginning in the middle of the twentieth century, and resulted in many additional stringencies.

Regardless of their specific halakhic orientations, all the authorities delivering rulings on modesty issues made assumptions regarding the limits of an individual’s ability to contend with inherent evil inclination. The fashioning of modesty strictures during these years was intended to aid the individual in his or her constant struggle with the sexual temptations that lie in wait at every corner. These rules are normally directed to the public at large; we also witness the occasional appearance of detailed recommendations and instructions for exceptional individuals wishing to adopt personal stringencies and to act with greater piety and abstinence, as has been the case throughout Jewish history.

The religious Zionist society in The Land of IsraelEretz Yisrael, before and after the establishment of the state, until the 1960s, was more receptive to the values and life styles of Western culture. The reality of life in a mixed society seemed appropriate and not essentially contradictory to the bounds of modesty. This attitude was clearly influenced by a principle from the time of R. Eliezer ben Joel of Bonn, that, on the grounds of “regilut,” mixed activity by boys and girls or men and women would not necessarily result in sexual stimuli. The ideals of female equality and the participation by women in all spheres of life also aided in justifying the a priori reality of a mixed society.

Beginning in the late 1960s, this ethic of modesty changed significantly, due to the increasing influence on the religious Zionist society of the Merkaz ha-Rav school (after the yeshivah by this name). This rising influence was fed by the euphoria of the Six Day War, the massive transition to extensive settlement activity throughout Judea and Samaria (which was highly esteemed in religious Zionist circles) and the impressive development of religious education in Israel, with the establishment of the Bnei Akiva yeshivah system, the Hesder yeshivot (incorporating military service with traditional studies), seminaries for high-school girls, and pre-military academies. At the same time, the Merkaz ha-Rav orientation succeeded in effecting a minor “revolution” in regard to the bounds of modesty that had hitherto been practiced in religious Zionist society. Concepts unique to the teachings of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook related to a metaphysical perception of the essential sanctity of the Israelite nation, and the identification of the Zionist enterprise as the “beginning of the Redemption” gained dominance. Such concepts also entered the considerations and reasons affecting the rules governing modesty and contributed to the development of a trend, primarily among the young, of enhanced observance and additional stringency in everything related to modesty. The new elements now joining the vocabulary of the public discourse on modesty were based on the mythical-metaphysical concept of Jewish nationalism and a series of associated concepts, such as “Jewish sanctity,” “Jewish modesty,” and the “purity of the Jewish people” (as opposed to “non-Jewish impurity”). The discussion of questions of individual modesty would no longer be distinct from national religious ideology, nor from religious Zionist ideology. The concept of religious-national redemption and the experience of its political-historical realization require careful observance of increasingly stringent bounds of modesty. The concept of ervah and the proper measures to be taken to ensure modesty are no longer exclusively dependent upon the sexual stimulation of the individual, but are measured against possible harm to the “sanctity of Israel.” These external manifestations of modesty are meant to represent internal sanctity; accordingly, the individual who does not act in a properly modest manner blemishes Jewish sanctity. The new modesty discourse contains statements such as “modesty is one of the characteristic features of Israel,” which was voiced by R. Shlomo Aviner (Aviner 1977/1978: 3). Immodesty corrupts this holiness: not only does it harm the individual who entertains sinful thoughts, it also inevitably flaws the general Jewish sanctity. In consequence, the value of modesty has risen and occupies a decisive position in the religious value system. In the age of redemption, emphasis is to be placed on these values, which are declaratively and explicitly expressed in “halakhic meticulousness regarding modesty.”

These changes encompass many areas and are marked in dress style, through gender separation in the schools, separation at various public events, the reinstitution of matchmaking, the preclusion of joint singing by men and women (even of zemirot at the Sabbath table) and other stringencies. Despite the different, and unique, infrastructure of religious Zionism, many practices and strictures related to modesty resemble those observed in ultra-Orthodox society. In this manner, metaphysical and mythical concepts were embedded in the halakhic discourse of the Merkaz ha-Rav circle and incorporated in the normative halakhic guidelines for a sexually modest lifestyle by the individual.

In what is still—despite the greater opportunities for women’s Jewish studies—a fundamentally patriarchal section of society, the strictures regarding modesty apply primarily to women. They are excluded from the single-sex activities that take place in the synagogue or the Houses of study (of Torah)bet ha-midrash and it is they whose natural desire to combine the aesthetic with the utilitarian is more severely circumscribed than that of men, to whom conformity of dress and appearance seems more acceptable. Even the Jewish studies which are now increasingly available to women are far more limited than those deemed necessary for men. Thus single-sex education in fact reinforces the inferior status of women on grounds of modesty.

Primary Sources

Abraham David of Posqueires. Ba’alei ha-Nefesh, ed. Yosef Kapah. Jerusalem: 1978.

Alashkar, Moses ben Isaac. She’eilot u-Teshuvot. Sabbioneta: 1553.

Auerbach, Solomon Zalman. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Minhat Shelomo. Jerusalem. 1986–1999.

Aviner, Shlomo. “From Whom to Hear the Megillah [the Book of Esther]” (Hebrew). Ha-Zofeh, February 20, 2004, Musaf: 4.

Aviner, Shlomo Hayyim Hakohen. Ezem me-Azamay, Your Sons Like Olive Saplings around Your Table: Family Planning and the Prevention of Contraception (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1984.

Aviner, Shlomo. “Dancing and the Laws of Modesty” (Hebrew). Ha-Ma’ayan, 18/1 (1977/1978): 3–16 (= idem, Gan Naul: Aspects of Modesty [Jerusalem: 1985]: 55).

Azulai, Hayyim Joseph David Azulai, She’eilot u-Teshuvot Yosif Omez. Leghorn: 1798.

Baer, Shabbetai. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Be’er Esek. Venice: 1674.

Bahya ben Asher, Rabbenu Bahya: Commentary on the Torah (Hebrew), ed. Hayyim Dov [Charles B.] Chavel. Jerusalem: 1966.

Benjamin Ze’ev ben Mattathias of Arta. Shei’ilot u-Teshuvot Binyamin Ze’ev. Venice: 1539 (Jerusalem: 1989).

Chavel, Charles B. Maimonides’s Sefer ha-Mizvot ... with the Critical Comments of Nahmanides (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1981.

David ha-Kohen, She’eilot u-Teshuvot ha-Ra-Da-Kh. Ostrava: 1537–1538.

De Vidas, Elijah. Reshit Hokhmah. Venice: 1579.

Genesis Rabbah. Judah Theodor and Hanokh Albeck, eds., Midrash Bereshit Rabbah. Jerusalem: 1965.

English translation: H. Freedman and Maurice Simon, Midrash Rabbah: London and Bournemouth: 1951, vol. 1.

Eliezer ben Joel of Bonn. Sefer Ravyah, ed. Victor [Avigdor] Aptowitzer. Jerusalem: 1964.

Epstein, Jehiel Michael. Arukh ha-Shulhan. Orah Hayyim: Pietrkow: 1903–1907.

Feinstein, Moshe. Iggerot Moshe. New York and Bnei Brak: 1959–1985.

Ganzfried, Solomon. Kizur Shulhan Arukh. English translation by Hyman E. Goldin, Code of Jewish Law. New York: 1961.

Grodzinski, Hayyim Ozer. Ahiezer. Vilna: 1922–1939.

Heller, Yom Tov Lipmann. Maadanei Yom Tov ve-Divrei Hamudot (published with the commentary by R. Asher ben Jehiel). Furth: 1745.

Horowitz, Isaiah. Shenei Luhot ha-Berit. Amsterdam: 1649.

Isaac ben Joseph of Corbeil. Sefer Mizvot Katan. Constantinople: 1510.

Israel Meir ha-Kohen, Mishnah Berurah. First edition: Warsaw: 1894–1907.

Jaffe, Mordecai. Levushim. First editions: Lublin, Prague, Cracow: 1590–1604.

Jonah ben Abraham Gerondi. Commentary on Avot (Hebrew). Berlin-Altona: 1848.

Kallah = Kallah, trans. J. Rabbinowitz. In Minor Tractates, edited by Abraham Cohen. London: 1984.

Katzenellenbogen, Meir ben Isaac. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Ma-h-a-r-a-m Padua. Venice: 1553.

Kook, Abraham Isaac. Iggerot ha-Re’ayah. Jerusalem: 1984.

Luria, Solomon ben Jehiel. Yam shel Shlomo. (Various publication dates for the different tractates).

Maggid of Mezirech, Dov Baer. Maggid Devarav le-Ya’akov. Jerusalem: 1976 (first edition: Korets: 1781).

Maimonides, Moses. The Guide of the Perplexed, trans. Shlomo Pines. Chicago: 1964.

Maimonides, Moses. Sefer ha-Mizvot. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, The Commandments. London and New York: 1967.

Numbers Rabbah. In Midrash Rabbah. Vilna: 1887.

Maimonides, Mishneh Torah. (Trans. of Hil. Ishut in: Isaac Klein, The Code of Maimonides, Book Four: The Book of Women. New Haven and London. 1972).

Mann, Jacob. “Fragments of Midrashim on Genesis and Exodus from Geniza Manuscripts,” The Bible as Read and Preached in the Old Synagogue: A Study in the Cycles …, vol. 1, Hebrew section. Cincinnati: 1940; New York: 1971.

Margaliot (Margulies), Reuben, ed. Sefer Hasidim. Jerusalem: 1970.

Midrash Sekhel Tov, ed. Solomon Buber. Berlin: 1900.

Ramban (Nahmanides). Commentary on the Torah, trans. Charles B. Chavel. New York: 1971.

Ouziel, Ben-Zion Meir Hai. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Mishpatei Uziel. Jerusalem: 1947–1964.

Schremer, Adiel. Male and Female He Created Them: Jewish Marriage in the Late Second Temple, Mishnah and Talmud Periods (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 2003.

Schremer, Adiel. “Men’s Age at Marriage in Jewish Palestine of the Hellenistic and Roman Periods” (Hebrew). Zion 61,1 (1996): 45–66 (=Yisrael Bartal and Isaiah Gafni, eds., Sexuality and the Family in History [Hebrew]. Jerusalem: 1995: 43–70).

Seder Eliyahu Zuta, ed. Meir Friedmann [Ish-Shalom], Pseudo-Seder Eliahu Zuta (Derech Erec und Pirke R. Eliezer). Vienna: 1904 (Jerusalem: 1969).

Sefer ha-Hinukh. English translation: Sefer haHinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education ascribed to Rabbi Aaron haLevi of Barcelona, trans. Charles Wengrov. Jerusalem and New York: 1978.

Shabbetai ben Meir ha-Kohen. Siftei Kohen. First ed.: Cracow: 1646 (from 1674, in the printed editions of Shulhan Arukh, Yoreh Deah).

Sirkes, Joel. Bayit Hadash. Cracow: 1631–1639.

Sofer, Moses. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Hatam Sofer. First ed.: Pressburg and Vienna: 1855–1864.

Steinhardt, Joseph. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Zikhron Yosef. Furth: 1773.

Tishbi, Isaiah. The Wisdom of the Zohar: An Anthology of Texts, trans. David Goldstein. Oxford: 1989.

Trani, Moses ben Joseph. She’eilot u-Teshuvot ha-Mabit. Venice: 1629–1630; Lvov: 1861.

Tzava’at ha-Rivash: The Testament of Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov, trans. Jacob Immanuel Schochet. Brooklyn: 1998.

Waldenberg, Eliezer Judah. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Ziz Eliezer. Jerusalem: 1945.

Weinberg, Jehiel Jacob. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Seridei Eish. Jerusalem: 1961–1969.

Yosef, Ovadiah. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Yabi’a Omer. Jerusalem: 1954.

Zeev Wolf of Zhitomer, Or ha-Me’ir. Zhitomer: 1787.

Secondary Sources

Abarbanell, Nitza. Eve and Lilith (Hebrew). Ramat Gan: 2002.

Ahituv, Yosef. “On the Attribution of Demonic Traits to Women” (Hebrew). Mahanayim 14 (2003): 145–159.

Ahituv, Yosef. “Modesty between Mythos and Ethos” (Hebrew). In A Good Eye: Dialogue and Polemic in Jewish Culture. A Jubilee Book in Honor of Tova Ilan, edited by Yosef Ahituv et al. (Hebrew). Tel-Aviv: 224–263. 1999.

Barkai, Ron. “Greek Medical Traditions and Their Impact on Conceptions of Women in the Gynecological Writing in the Middle Ages.” In A View into the Lives of Women in Jewish Societies (Hebrew), edited by Yael Azmon, 115–142. Jerusalem: 1995.

Barkai, Ron. Science, Magic and Mythology in the Middle Ages (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1987.

Benayahu, Meir. Studies in Memory of the Rishon Le-Zion R. Yitzhak Nissim, vol. 6: Standings and Sittings (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1985.

Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel. “The Social Teaching of R. Johanan Luria” (Hebrew). Zion 27 (1962): 166–198.

Boyarin, Daniel. Carnal Israel: Reading Sex in Talmudic Culture. Berkeley: 1993.

Berman, Saul J. “Kol ‘Isha.” In Rabbi Joseph H. Lookstein Memorial Volume, edited by Leo Landman, 45–66. New York: 1980.

Biale, David. Eros and the Jews: From Biblical Israel to Contemporary America. New York: 1992.

Bonfil, Reuben. “Aspects of the Social and Spiritual Life of the Jews in Venetian Territories at the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century” (Hebrew). Zion 41 (1976): 68–96.

Breisch, Mordecai Jacob. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Helkat Ya’akov. Jerusalem: 1951–1966 [Tel Aviv: 1992].

Cohen, Jeremy. “Sexuality and Intentionality in Rabbinic Thought of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries.” Te’uda 13: Marriage and the Family in Halakhah and Jewish Thought (Hebrew) (1997): 155–172.

Cohen (Kohen), Yehezkel. Woman in Public Leadership: The Dispute concerning Women’s Religious Council Membership (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1991.

Cohen, Yehezkel. “The Disagreement between Rabbis Kook and Ouziel, of Blessed Memory, Concerning Women’s Suffrage” (Hebrew). In Peninah: Peninah Rappel Memorial Volume, edited by Dov Rappel. Jerusalem: 1989.

Dinari, Yedidya. “The Profanation of the Holy by the Menstruant Woman and ‘Takanat Ezra’” (Hebrew). Te’uda 3 (1983): 17–37.

Dinary, Yedidya. “The Impurity Customs of the Menstruant Woman: Sources and Development” (Hebrew). Tarbiz 49 (1980): 302–324.

Enziklopedia Talmudit (Talmudic Encyclopedia), ed. Shlomo Josef Zevin. Jerusalem: 1952 and additional printings.

Ellinson, Eliakim Getsel. Woman and the Commandments. Book Two: Walk Modestly: Elucidated Halakhic Sources (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1981.

Friedhaber, Zvi. “Dance Customs in the Jewish Yishuv of Jerusalem before World War I” (Hebrew). Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Folklore 11–12 (1990): 139–151.

Friedhaber, Zvi. “The Tanzhaus in the Life of Ashkenazi Jewry during the Middle Ages” (Hebrew). Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Folklore 7 (1984): 49–60.

Friedhaber, Zvi. “Dancing in the Life of Jewish Sefardic Communities as Reflected in the Communal Regulations and Responsa Literature” (Hebrew). In The Sephardi and Oriental Jewish Heritage: Studies, edited by Issachar Ben-Ami, 347–353. Jerusalem: 1982.

Friedhaber, Zvi. “Jewish Folk Dance Customs as Reflected in the Memorial Literature of the European Jewish Communities” (Hebrew). Proceedings of the Fifth World Congress of Jewish Studies, vol. 4. 1973: 109–115.

Friedman, Menachem. Society and Religion (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1977.

Friedman, Mordechai A. “Halakhah as Evidence for the Study of Sexual Mores among Jews in Medieval Islamic Countries: Face Coverings and Mut’ah Marriages.” In A View into the Lives of Women in Jewish Societies: Collected Essays (Hebrew), edited by Yael Azmon, 143–160. Jerusalem: 1995.

Gottleib, Dov. Yad Ketanah. Jerusalem: 1994.

Grossman, Avraham. Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe, trans. Jonathan Chipman. Waltham, MA and Hanover: 2004.

Grossman, Avraham. “The Relationship between Halakhah and Economy in the Status of the Jewish Woman in Early Ashkenaz” (Hebrew). In Religion and Economy: Connections and Interactions, edited by Menahem Ben-Sasson. Jerusalem: 1995.

Grossman, Avraham. “The Attitude of R. Menahem ha-Meiri towards Women” (Hebrew). Zion 67,3 (2002): 253–292.

Halamish, Moshe. “‘Le-Shem Yihud’ and Its Evolutions: In Kabbalah and in Halakhah” (Hebrew). Asufot 10 (1995): 135–159.

Harari, Moshe. Mikraei Kodesh: Laws of the Seder Night (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1993.

Henkin, Yehudah Herzl. She’eilot u-Teshuvot Benei Banim. Jerusalem: 1980.

Hirschensohn, Hayyim. Malki ba-Kodesh (Hebrew). St. Louis: 1919.

Higger, Michael. Masekhtot Ze’irot (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1970.

Horowitz, Elliot. “Between Masters and Maidservants in the Jewish Society of Europe in Late Medieval and Early Modern Times” (Hebrew). In Sexuality and the Family in History, edited by Yisrael Bartal and Isaiah Gafni, 193–212. Jerusalem: 1995.

Idel, Moshe. “Female Beauty: A Chapter in the History of Jewish Mysticism.” In Within Hasidic Circles: Studies in Hasidism in Memory of Mordecai Wilensky (Hebrew), edited by Immanuel Etkes et al., 317–334. Jerusalem: 1999.

Idem. “Sexual Metaphors and Praxis in the Kabbalah.” In The Jewish Family: Metaphor and Memory, edited by David Kraemer, 197–224. New York: 1989.

Idel, Moshe. “Sitre ‘Arayot in Maimonides’ Thought.” In Maimonides and Philosophy: Papers Presented at the Sixth Jerusalem Philosophical Encounter, May 1985, edited by Shlomo Pines and Yirmiyahu Yovel. Dordrecht: 1986.

Kasher, Menahem M. Torah Shelemah (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1992.

Katz, Jacob. “Traditional Society and Modern Society” (Hebrew). In Jewish Nationalism: Essays and Studies. Jerusalem: 1979.

Katz, Jacob. “Reciprocal Influence between Religion and Society in the Period of the Emancipation” (Hebrew). In Religion and Society: Lectures Delivered at the Ninth Convention of the Historical Society of Israel, December 1963, 135–146. Jerusalem: 1964.

Katz, Jacob. “Marriage and Sexual Life among the Jews at the Close of the Middle Ages” (Hebrew). Zion 10 (1944–1945): 21–54.

Levin, Mordechai. Social and Economic Values in the Ideology of the Period of the Haskalah (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 1975.

Liebes, Yehuda. “Zohar and Eros” (Hebrew). Alpayim 9 (1994): 67–119.

Ross, Tamar and Gellman, Yehudah (Jerome). “The Impact of Feminism on Orthodox Jewish Theology.” In Multiculturalism in a Democratic and Jewish State: The Ariel Rosen-Zvi Memorial Book (Hebrew), edited by Menachem Mautner, Avi Sagi and Ronen Shamir, 443–464. Tel Aviv: 1998.

Roth, Cecil. The Jews in the Renaissance. Philadelphia: 1959.

Shilo, Margalit. Princess or Captive: Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 (Hebrew). Haifa: 2001.