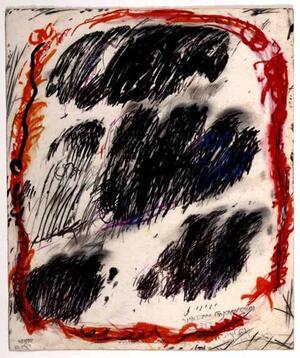

Aviva Uri

Aviva Uri was an influential Israeli artist. Born in Safed, she studied painting with David Hendler, with whom she later lived. During the 1950s she was influenced by abstraction, surrealism, and Chinese and Japanese drawing. In 1952, she received the Dizengoff Prize and in 1957 she exhibited her work at the Tel Aviv Museum. She was appreciated for her abstract scribbles that expressed anxiety and distress. In the 1960s she was involved in exhibitions of the Ten Plus group and returned to painting to express social and anti-war protest. The feeling of mourning in her works grew in the 1980s, with the Lebanon War and the death of David Hendler. She continued to innovate and influence other artists until her death in 1989.

Among art lovers in Israel and in the inner circles of artists, Aviva Uri is considered a myth. Major artists such as Raffi Lavie, Moshe Gershuni, and Igael Tumarkin see her work as a turning point in the story of Israeli art, and note her influence on their work and her meaningful role in the shaping of generations of artists in Israel.

Aviva Uri attained this status even though she did not take part in the constitutive mechanisms of the art world: she never studied at an art school, never belonged to a leading art group, and was not active in institutions of art teaching that open channels of influence and accord one a position in the art discourse. Aviva Uri’s unique path in the art world is interwoven with the story of her life.

Early Life and Family

Aviva Uri was born on March 12, 1922, in Safed, to Azriel Uri and Rachel (Bronfszum), refugees from the Ukraine and Socialist Zionists who settled in The Land of IsraelErez Israel in 1920. Her mother, a dentist by profession, died a short time after Aviva was born, aged 25. It may be assumed that Aviva, who first heard the story of her mother’s death when she was fourteen, connected this event to her own birth, and that this connection influenced her world picture. Her father, who was active in the Zionist Organization, re-married, to Gissia Livorkin, who was also a dentist. After their marriage the couple moved with little Aviva to Givatayim, and afterwards to Ramat Gan.

It seems that from her childhood on Aviva Uri cultivated longings for a life of art. When she was seventeen she gave expression to her dilemma, the choice between her artistic aspirations and a life of love: “I spread out my hands towards you, the anonymous one, who is there somewhere, or does not exist at all. […] And then again the inner imperative: if you want to create art, you have to be first an artist, and then a woman” (from her diary, in the possession of her daughter, Rachel Yampuler, Tel Aviv).

Aviva’s mother Rachel and her step-mother Gissia, independent women both, were part of the elite pioneering group in Erez Israel that profoundly influenced the shaping of the patterns of life and the political institutions of pre-state Israel. On the face of it—an egalitarian society; in fact—a society that did not manage to eradicate the old stereotype that left the core of representation to the men. The message that seeped into Aviva Uri’s world contained an ostensible contradiction between gender identity and the realization of creative aspirations. This message was reinforced by a domineering father who did not support his daughter’s leanings towards art, and responded harshly, raising his arm to her, and destroying her paintings.

Personal Life

When she was 20 (in 1941), Aviva Uri married Moshe Levin, who worked at the diamond exchange in Ramat Gan. But her longings for a life of art were not entirely suppressed. A few years after her wedding a decision matured in her, and she moved, with her infant daughter (Rachel, named after her mother), into the home of an artist who was 20 years her senior, David Hendler (in 1947), and who became her supportive partner, in both life and art, until his death in 1984. Hendler, an esteemed artist, had studied drawing in Prague, arrived in Israel in 1924, and in 1944 became Aviva Uri’s teacher. He was penniless, but Aviva Uri stayed with him, and he passed on to her the knowledge he had accumulated, influenced her with his rare talent, and was open to nurture her unique inner fire without shaping her in his own image.

Among artist couples, it is frequently the woman who gives up her art for the sake of her partner’s art. The relationship between David Hendler and Aviva Uri was different: Uri was the artist, while Hendler was the one who sacrificed his art for her, as it were fulfilling himself through her. Under Hendler’s guidance, Aviva Uri gradually improved her drawing technique, and with his support she was able to examine her inner world more deeply. It would seem that the fact that she had not studied at an art school had an influence on the independent line that she developed. Aviva Uri’s drawing offered a new option that the artists of the time had been craving for: a personal line, free of the mannerisms of “painterly” or “cultured” “sensitivity,” or, as Uri herself put it: “I didn’t follow the way taken by all the artists of my age in that period, who imitated their teachers when the ‘Lyrical Abstract’ was dominant and French art was the teacher of the way. This did not enthuse me at all, I sought something entirely different, not the ‘illusion’ of paint on the canvas, and not the making of ‘beautiful pictures’. […] I was attracted immediately to the pure line— drawing! The line was I” (from a letter to Gideon Ofrat, 1977).

Artwork and Career

Already in 1949 Aviva Uri held her first solo exhibition at the Katz Gallery in Tel Aviv, and in 1952 she was awarded the prestigious Dizengoff Prize and participated in select group exhibitions in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. She attained public recognition following the solo exhibition of her drawings at the Tel Aviv Museum in 1957 (curated by the Museum’s director, Eugen Kolb). The exhibition seeped into the depths of the art scene’s consciousness with its directness and its condensed expressiveness. At that time, and even for a decade after this, drawing was still perceived as a secondary means after painting, and had no visibility in the public mind as an independent artistic discipline. Aviva Uri’s solo exhibition, in which drawing was presented naked and unembellished, was quite a daring innovation. Raffi Lavie has said, more than once, that this exhibition of Aviva Uri had had a constitutive influence on his work.

In 1959, Uri was chosen by Eugen Kolb to represent Israel at the First Biennial of Young Artists in Paris. Years later, she established her position as an esteemed artist on the local scene with a solo exhibition at The Israel Museum, Jerusalem (1971, curator: Yona Fischer), which was followed, several years afterwards, by a solo exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum (1977, curator: Sarah Breitberg). In 1984 she attained to the beginnings of international recognition, with a solo exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (curators: Ed Paterson and Yona Fischer). Aviva Uri was not present at this exhibition—a day before the opening, her life-partner, the artist David Hendler, passed away, and Aviva Uri found it difficult to come to terms with the loss. In the last five years of her life, without Hendler, she created relatively large, expressive drawing works in color, which she described, in the context of the Lebanon War, in these words: “The line of these days is a line whose past is Auschwitz and Hiroshima, and whose future is missiles of destruction” (Aviva Uri, “The Line” [in Hebrew], in Doreet Levitté, Aviva Uri, 1986, p. 20).

Legacy

Aviva Uri died on September 1, 1989. A retrospective exhibition of her oeuvre was held in 2002 at the Museum of Art, Ein Harod (curator: Galia Bar Or, in collaboration with Jean-François Chevrier). Aviva Uri has become engraved in our memory as a woman who realized her life as an artist, a gifted draftswoman whose work touched the roots of her existence and influenced an entire generation of artists.

In the course of fifty years of creation she engaged only in drawing, uncompromisingly and without an iota of faking, and established her central place in the history and the language of Israeli art. She developed a distinctive language, both intuitive and analytical, of her own, with a line that responds to the inner rhythm of the psyche and breathes the spirit of the time.

Hebrew

Books

Bar Or, Galia, and Jean-François Chevrier. Aviva Uri, Tel Aviv: 2002.

Levitté, Doreet. Aviva Uri, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv: 1986.

Yampuler, Rachel. Rise, Awake, For Your Light Has Come, Tel Aviv: 2002

Yeshurun, Helit, ed. Yona Wollach – Aviva Uri: The Face Was an Abstraction: Tel Aviv, 2000.

Articles in Newspapers and Journals

Bar-Kadma, Emmanuel. “A Gift of Love.” Yediot Aharonot: Seven Days, February 6, 1987.

Bar-Kadma, Emmanuel. “Who’s This Young Woman Who Draws Like Picasso?” Yediot Aharonot, September 4, 1989.

Baruch, Adam. “Aviva Uri: It Wasn’t Bad.” Ha-ir, December 22, 1998.

Baruch, Adam. “A Sure Asset.” Yediot Aharonot: Seven Days, April 15, 1977.

Baruch, Adam. “It Wasn’t Bad.” Yediot Aharonot: Seven Days, September 8, 1990.

Barzel, Amnon. “Aviva Uri.” Haaretz, March 5, 1971.

Breitberg-Semmel, Sarah. “Aviva Uri.” Studio 137 (November 2002): 24–25.

Breitberg-Semmel, Sarah. “The Icarus Quality (The Mountain is the Wind).” Kav 6–7 (June 1984).

Direktor, Ruti. “Awake Light.” Ha-ir, January 2, 2003.

Fischer, Yona. “Aviva Uri.” La-Merhav, January 18, 1957.

Ginton, David. “Death, Destruction, Fall.” Tel Aviv, May 1988.

Givon, Noemi. “My Landscape is the World.” Haaretz Weekend Supplement, October 19, 1979.

Karpel, Dalia. “Requiem for a Bird.” Ha-ir, September 8, 1989.

Karpel, Dalia. “When a Mother Hates.” Ha-aretz Weekend Supplement, November 15, 2002.

Lavie, Raffi. “Aviva Uri.” Ha-ir, April 29, 1988.

LeVitté, Doreet. “Aviva Uri’s Viewing Stance.” Kav 6–7 (June 1984).

Manor, Dalia. “The Bird of Art and Its Forefathers”, Haaretz Literary Supplement, February 5, 2003.

Maor, Haim. “The Line That Got Burned”, Al ha-Mishmar: Hotam, September 8, 1989.

Ofrat, Gideon. “The Bird as a Metaphor.” Studio 6 (December 1989):18–19.

Ofrat, Gideon. “Drawing as a Mask.” Tziyur ve-Pisul 15 (1977): 10–17.

Omer, Mordechai. “‘The Great Mother’ in Aviva Uri.” Motar 4 (1996): 101–104.

Shefi, Smadar. “A Face Like a Mask”, Haaretz, January 17, 2003.

Shkolnik, Hila. “Who’s Hiding Behind the Mask.” Kolbo, December 20, 2002.

Tamir, Tali. “Probability Death.” Haaretz, September 8, 1989.

Tumarkin, Igael. “It’s OK to Get Angry.” Devar Ha-Shavu’a, September 8, 1989.

Uri, Aviva. “The Line.” Kav 6–7 (June 1984).

Zach, Natan. “Aviva Uri.” Davar: Massa, April 22, 1960.

Zalmona, Yigal. “Aviva Uri’s Drawings.” Ma’ariv, May 23, 1975.

English

Goldfine, Gil. “Energy in Black”, The Jerusalem Post, December 27, 2002.