Zoya Cherkassky

Zoya Cherkassky is a prominent Israeli artist. She was born in Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1976, and moved to Israel in 1991. Immigration became one of the major themes in her later work. She is most famous for her 2018 exhibitions Pravda and Soviet Childhood, which captured not only Cherkassky’s own and her family’s experience, but the collective memory of her generation. Her work exhibits a social satire that is both humorous and moving, nostalgic and anti-nostalgic. Her other notable exhibitions include Collectio Judaica (2003), Action Painting (2006), and The New Barbizon: Back to Life (2017). Cherkassky works in a range of media and styles, synthesizing traditional painting techniques with vernacular tools and moving freely between allusions to the European canon and contemporary art.

Zoya Cherkassky is one of the most prominent artists in Israel in the twenty-first century. She works in a range of media and styles, synthesizing traditional painting techniques with vernacular tools and moving freely between allusions to the European canon and contemporary art. Her work is often marked by humor, irony, and satire. Cherkassky’s artistic approaches reflect her hybrid professional training and personal background.

Early Life and Education

Cherkassky was born in Kyiv in on December 24, 1976, an only child to a privileged—by Soviet standards—Jewish-Ukrainian intermarried family. Her father, Michael Cherkassky was an architect, and her mother, Alla Romm, an engineer. Cherkassky’s childhood talent earned her a place in an art academy, where she received early training in classical drawing and painting technique. In 1991, when Cherkassky was fourteen, the family immigrated to Israel, just as the Soviet Union was collapsing. Immigration, the collective experience of nearly a million Soviet Jews who arrived in Israel at that time, left an indelible mark on the young artist and became one of the major themes in her later work.

In Israel, Cherkassky was exposed to contemporary Western art theory and practice, first at the Thelma Yellin High School in Tel Aviv and later at HaMidrasha School of Art at Beit Berl College. Among her most influential teachers there were such Israeli art figureheads as Boaz Arad, Roee Rosen, and Uri Katzenstein. Cherkassky’s graduation project (co-created with Ruth Nemet) was shown at the Israel Museum, a sign of a promising career. The promise delivered: Cherkassky went on to become a prolific artist, with numerous solo and group exhibitions nationally and internationally.

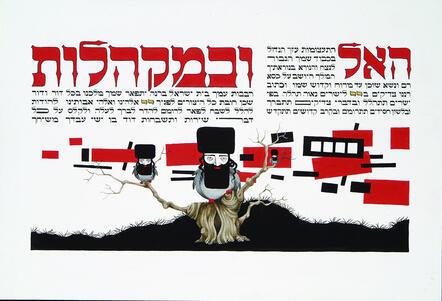

Collectio Judaica: In Search of Jewish Iconography

Cherkassky’s first major solo exhibition was 2003’s Collectio Judaica (Cherkassky, 2004). The show’s multimedia works, spanning sculpture, painting, jewelry, and graphic art, focused on representations of Jews. Cherkassky’s explorations of Jewish iconography engaged provocatively with anti-Jewish stereotypes and with the traditional Jewish prohibition against the graven image. She found inspiration in diverse sources, from illuminated manuscripts to the Russian avant-garde to antisemitic caricature. Reversing Jewish representations in the famous Birds' Head The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah—the medieval Haggadah depicting Jewish men and women with human bodies but with the head of birds—she drew figures with the bodies of birds and the heads of Hasidic rabbis. Stark black and red diagonal lines across her Haggadah pages recall the constructivist aesthetics of El Lissitsky and the Bauhaus style of Tel Aviv architecture, while the four-letter hidden name of God is evoked by four blank squares, echoing Kasimir Malevich’s suprematism. Another painting presents the figure of a disappearing rabbi, visualizing rabbinical arguments on representation: the first image depicts a rabbi in full figure but without facial features, the second rabbi is depicted without the head, whereas the third rabbi is a spectral absence. Included in the exhibition are also golden brooches in the shape of Jewish stars, problematizing Holocaust iconography. Already in this relatively early work, Cherkassky used her superb technical skills to engage with a range of art traditions and express social commentary.

Action Painting and Other “Art about Art”

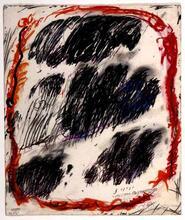

Cherkassky’s next major project, the exhibition Action Painting (Cherkassky, 2006), marked her turn to “art about art.” Action Painting tackled the role of art in society: Cherkassky juxtaposed the transgressive, radical nature of art with the complacency of art patrons and institutions. To make a statement, she placed piles of excrement made of bronze, a common material for monumental sculpture, at the entrance to the exhibition. Other works echoed this provocative juxtaposition: large-scale paintings depict violent scenes set in museums, such as a pack of wild dogs racing through the halls and an enormous naked woman towering over a shocked public.

Cherkassky’s work in “art about art” culminated in her next exhibition, Olga Sviblova is Shit or The End of the Critical Discourse (2009, Guelman Gallery, Moscow). In the same way in which Action Painting commented on art institutions, Olga Sviblova took up clichés of revolutionary art and satirized the contemporary Russian art scene. Cherkassky created this exhibition with Avdey Ter-Oganyan, an exilic Russian artist and activist, whom she met during her sojourn in Berlin from 2005 to 2009. Ter-Oganyan became Cherkassky’s mentor, helping her to reconcile her contemporary practice with her background in Soviet art without reducing it to propaganda.

Pravda Beyond Propaganda

Ter-Oganyan’s influence became particularly important in the next chapter of Cherkassky’s career, resulting in two major exhibitions: Pravda (Cherkassky, 2018), at The Israel Museum, and Soviet Childhood, (Cherkassky, 2018), at Rosenfeld Gallery in Tel Aviv and later at Fort Gansevoort Gallery in New York and Los Angeles. Pravda, the culmination of nine years of work, was a significant departure for the artist, in terms of both subject matter and artistic approach. For a subject, Cherkassky turned her gaze to her Soviet youth and her immigration to Israel. Working in a variety of media, from markers to oil painting, she captured not only her own and her family’s experience, but also a snapshot of the collective memory of her generation. As to approach, the artist turned to what she called “painting from observation”—a practice that, in contrast to conceptual art, put the artist in touch with her surroundings, honing her ability to perceive and interpret reality (Cherkassky, interview with author). While working on these exhibitions, Cherkassky traveled to Kyiv and revisited sites of her childhood and of Jewish collective memory, from the Holocaust to the Soviet era to the upheavals of Perestroika. Ultimately, she found a new artistic language, combining Russian realism, American Scene Art, European Old Masters, and the Soviet school of illustration and caricature to create a social satire that is both humorous and moving, nostalgic and anti-nostalgic.

Pravda showed both the old country and the new, the before and the after, satirizing in equal measure the immigrants and the hosts. The key work was the diptych “1991 in Ukraine” and “Friday in the Neighborhood.” The first painting presents a snapshot of the brutal reality in early post-Soviet Ukraine, compositionally evoking Pieter Bruegel’s “The Hunters in the Snow” (1565). Several scenes scattered over a canvas show assault, rape, and other violent actions. In the background, two demonstrations are about to clash—one with a red Communist flag, another with a blue-and-yellow Ukrainian nationalist flag.

In contrast to the white snow in “1991 in Ukraine,” “Friday in the Neighborhood” is dominated by yellow sand, with palm trees and a camel indicating the Middle East. But similarly disturbing scenes unfold there: an elderly man rummages in a dumpster, drug addicts shoot up, someone gets stabbed, and a missile descends in the background. The setting might be different, but the despair and violence remain. The promise of immigration did not deliver, but there is nothing to be nostalgic about either.

Along with the “before” and “after,” Cherkassky’s Pravda was preoccupied with stereotypes, simultaneously displaying and deconstructing them with her signature sense of humor. Notable here is “Rabbi's Deliquium,” depicting a rabbi’s visit to a young family of Russian immigrants, who are in the process of conversion to Judaism. In the foreground, the table is set for a SabbathShabbat celebration, but the rabbi is caught in shock when he opens a pot to see a pig’s muzzle staring back at him. The painting pokes fun at the stereotypes of both new immigrants and religious institutions. The characters and the setting are painted in the broad style of a caricature, but the dynamic between characters is captured with such precision that the painting looks as it is about to spring into action. “I see myself as the Sholem-Aleichem of drawing,” comments Cherkassky (2012).

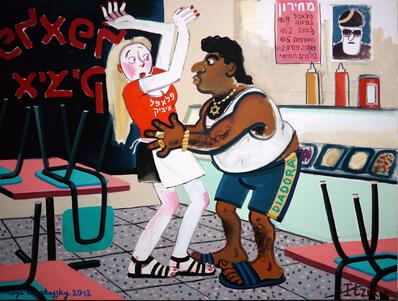

Cherkassky’s engagement with stereotypes can be controversial, as was the case with “Itzik,” a painting depicting a sexual assault on a “Russian” waitress by an Israeli restaurant owner. A blond, fair woman raises her hands defensively against a swarthy, hairy man with a hooked nose and an enormous gut. The painting raised the uncomfortable subject of sexual harassment that many new immigrant women experienced in 1990s Israel. But the characterization clearly relied on racist and antisemitic tropes. Although the painting critically engaged with these tropes in order to expose and deconstruct stereotypes of both immigrant women and local (particularly Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi) men, it proved contentious in Israel.

The New Barbizon: Back to Life

Cherkassky’s preoccupation with “painting from observation” brought her in contact with other artists with similar agendas. Together with four other female artists from the Former Soviet Union, she founded a group called the New Barbizon, after the Barbizon group in nineteenth-century France. Like Barbizon artists who came out of the studio to paint en plein air, the New Barbizons left the studio for the streets. The group went out on collective expeditions, setting up their painting equipment in urban sites, like a bus station or cafeteria. Inevitably, five artists painting together, sometimes on large-scale canvases, attracted attention and led to public interactions. These expeditions then became live actions, bringing the artists in touch with different kinds of people and involving them in the art-making as models or interpreters of local life. This method, says Cherkassky, “brings me out of the Tel Aviv bubble and makes me more political” (Cherkassky, interview with author). Indeed, the New Barbizon paintings are often set on the margins of society, depicting the everyday life of minorities: women, urban poor, African migrant workers, Bedouins. The work of the New Barbizon culminated in a 2017 group exhibit, The New Barbizon: Back to Life (Cherkassky et al, 2017).

One of the subjects of Cherkassky’s “painting from observation” has been life in an African village. Her husband, Hyacinth Obinna Nnadi, is from Nigeria and since the couple married in 2013, Cherkassky has traveled to Nigeria on family visits. While there, she “painted from observation” depicting street scenes, domestic life, community celebrations, and funerals. Over the years, these paintings amounted to a significant body of work. Some of them have already been shown (see Regarding Africa, 2016).

Responding to October 7

In October and November 2023, Zoya Cherkassky produced twelve mixed-media works on paper, collectively titled "October 7, 2023." This series responded, almost in real time, to the harrowing events of that day. Soon after, the series was exhibited at the Jewish Museum in New York and became an instant classic, symbolizing for audiences the world over the shock and horror of the attack.

Cherkassky’s series captures an immediate—which is not to say unmediated—response to national trauma, rather than personal trauma. In her response to the traumatic rupture, Cherkassky relies on multiple levels of adaptation and translation. The most significant of these is her adaptation of the Western art canon, whether modernist or proto-Renaissance, to the Israeli reality. For instance, the piece "7 Oct. 2023" draws a direct parallel to Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica" (1937). Like Picasso’s work, which responded to the bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, Cherkassky’s "7 Oct. 2023" captures the chaotic and brutal nature of the violence inflicted upon civilians. The stark black background and frantic, distressed figures convey a sense of horror and urgency, adapting the visual language of twentieth-century modernism to comment on present-day atrocities in Israel’s South. "Massacre of the Innocents" references Giotto’s fresco of the same title (1305-1306), which depicts the slaughter of infants under King Herod’s order. Cherkassky’s adaptation similarly portrays a tangle of bodies, evoking the historical resonance of this biblical massacre. By adapting Giotto’s imagery, Cherkassky bridges past and present, suggesting a continuity of human suffering and the cyclical nature of violence. Cherkassky’s "A Burnt Family" adapts Edvard Munch’s "The Scream" (1893). The figures, depicted with their hands to their heads and faces contorted in perpetual lament, echo Munch’s iconic portrayal of existential despair. Cherkassky’s shadowy figures on a pitch-black background capture a visceral, almost apocalyptic vision of the family’s anguish. The adaptations of these classical Western artworks also create temporal and geographical leaps—from biblical times or the Spanish Civil War to present-day Israel. These adaptations make the Israeli trauma universal, creating an emotional shortcut to access the audience’s identification with the suffering.

In addition to this key adaptation, Cherkassky’s series is marked by other acts of adaptation and translation. Like most Israelis, she did not experience the Hamas attack personally but rather through media reports. In the series, she “translates” the documentary language of news footage and images into her distinct visual style. By necessity, she also adapts her artistic style to depict the atrocities. Cherkassky’s work is normally characterized by humor and satire, but in this series, she adapts her style to the somber subject. As the artist herself said in the interview to the New York Times, “There’s just nothing funny about Oct. 7. There was nothing to be ironic about.” Taken together, these twelve works draw a direct line from individual psychological turmoil to broader societal devastation. This series exemplifies the power of art to serve as both a witness to and a means of processing national trauma.

Catalogs:

Cherkassky, Zoya. Soviet Childhood. Tel Aviv: Rosenfeld Gallery, 2018.

Cherkassky, Zoya. Pravda. Edited by Amitai Mendelsohn. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2018.

Cherkassky, Zoya, Olga Kundina, Anna Lukashevsky, Asya Lukin, and Natalia Zourabova. The New Barbizon: Back to Life. Edited by Yaniv Shapira. Ein Harod, Israel: The Mishkan Museum of Art, 2017.

Cherkassky, Zoya. Action Painting. Edited by Mordechai Omer. Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2006.

Cherkassky, Zoya. Collectio Judaica. Tel Aviv: Rosenfeld Gallery, 2004.

Russo, Karen, Ruti Nemet, Zoya Cherkassky, and Irina Birger. A Doll's House. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 2000.

Exhibitions:

Zoya Cherkassky, Exhibitions. Rosenfeld Gallery, Tel Aviv, 2001-2021. http://rg.co.il/artist/zoya-cherkassky/exhibitions/

Zoya Cherkassy, Lost Time. Curated By Alison M. Gingeras. Fort Gansevoort, online, 2020. https://www.fortgansevoort.com/online-exhibitions/zoya-cherkassy#tab:th…

Zoya Cherkassky, Pravda. Curated by Amitai Mendelsohn. The Israel Museum, 2018. https://www.imj.org.il/en/exhibitions/zoya-cherkassky

Zoya Cherkassky, Zoya Cherkassky:7 October 2023. The Jewish Museum, New York, December 15, 2023-March 18, 2024. https://thejewishmuseum.org/exhibitions/zoya-cherkassky-7-october-2023

Regarding Africa: Contemporary Art and Afro-futurism. Curated by Ruth Direktor. Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2016. http://www.africa-tamuseum.org.il/

Secondary literature:

Gershenson, Olga. “A Dancing Russian Bear.” Shofar 37, no. 2 (2019): 71-80.

Klein, Samuel and Zoya Cherkassky, Zoya. “Radical Storytelling.” Jewish Quarterly 52, no. 2 (January 2005): 12-16.

Kohn, Ayelet and Rachel Weissbrod. “‘Pravda’ in the Museum: Zoya Cherkassky’s Exhibition as a Case of Cultural (Self) Translation.” Journal of Specialised Translation 35 (January 2021): 144-165.

Moshkin, Alex. “Post-Soviet Nostalgia in Israel? Historical Revisionism and Artists of the 1.5 Generation.” East European Jewish Affairs 49, no. 3 (2019): 179-199.

Sorek, Ronit. “Zoya Cherkassky's Aachen Passover Haggadah: A Subversive Illuminated Manuscript.” Ars Judaica: The Bar-Ilan Journal of Jewish Art 12 (2016): 135-142.

Selected Interviews and Reviews:

Averbuch, Masha. “Even an exhibition at the Israel Museum will not make artist Zoya Cherkasky represent the state and curb her tongue.” Haaretz, January 4, 2018. [Hebrew]

Cherkassky, Zoya. Artist Talks on Art. [In Hebrew]. Tel Aviv Museum of Art, December 13, 2012. <https://vimeo.com/76824771>

Rozovsky, Liza. “Longing for Communism: The Painter Zoya Cherkassky Once Again Breaks Taboos.” Haaretz, August 24, 2015. [Hebrew] http://www.haaretz.co.il/gallery/art/.premium-1.2713887.19.09.2019 /

Setter, Saul. “Painter Zoya Cherkassky, Israel's Eternal Dissident, Is Embraced by an Unlikely Institution.” Haaretz, January 30, 2018.

Sheets, Hilarie M. “Lessons From the Plagues, Painted for Passover.” The New York Times. April 8, 2020.

Simon, Joshua. “Make Paintings Radical Again: Zoya Cherkassky.” Mousse Magazine 69 (2019): 134-137. http://moussemagazine.it/zoya-cherkassky-joshua-simon-2019/

Smith, Roberta. “Painted Valentines to the Soviet Era.” The New York Times, June 21, 2019.

Tracy, Marc. “The Artist Whose Oct. 7 Series ‘Attracts Fire’.” The New York Times, February 18, 2024.