Jewish clergy in the Civil Rights Movement

Unpack the roles, motivations, and challenges of Southern and Northern rabbis during the Civil Rights Movement.

Overview

Enduring Understandings

- The responsibilities of rabbis to their own congregations and the Jewish community can at times come into conflict with their responsibilities to the broader community.

- Jewish experiences and values informed Jewish relationships to the Civil Rights Movement in many different ways.

- Regional differences, particularly between the North and South, impacted rabbis' responses to the Civil Rights Movement.

Essential Questions

- Who were some of the Northern and Southern rabbis who participated in the Civil Rights Movement?

- What Jewish experiences and values motivated Jewish clergy to participate (and not participate) in the Civil Rights Movement?

- What roles do you think rabbis should play in relation to political and social issues today?

Notes to Teacher

This lesson may be taught in one long class session, or over two or more short class sessions. If you do not have time to cover all of the material, you may want to use shorter excerpts of the documents, just focus on the Milton Grafman sermon at the beginning of the lesson, or select other parts of the lesson that you think would be most meaningful to your students, such as the optional interview with a local clergyperson.

If you are teaching at a synagogue, consider using this lesson as a jumping off point for looking into your congregation’s own history of involvement (or lack of involvement) with the Civil Rights Movement and/or other social justice issues. (Also see the board meeting activity in Jews and the Civil Rights Movement: the Whys and Why Nots.)

Clergy in the Civil Rights Movement: Introductory Essay

Introductory Essay for Living the Legacy, Civil Rights, Unit 2, Lesson 6

Religious faith and religious leaders played a central role in the American Civil Rights Movement. In the 1950s, civil rights leadership and activism shifted from northern elite organizations focusing on legislative change (such as the NAACP) to southern communities focusing on direct action such as the Montgomery bus boycott, in which African American churches provided the meeting space, training ground, and religious inspiration. Many southern civil rights leaders came from a strong faith background and drew on religious values that asserted the equality and value of all people. In 1957, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. – in an effort to sustain the momentum of the Montgomery movement – brought together more than 100 African American ministers to found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). King served as the first president.

The student arm of the movement, which took on a leadership role in the 1960s with the sit-ins and the founding of SNCC (Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee), was also informed by religious values and led by seminary students, such as John Lewis, who identified their Christian conscience as their motivation to activism and who found great strength in their faith when they faced fear, danger, and violence. Integrating religious ideals of love, faith, non-violence, forgiveness, and brotherhood, Southern civil rights activists worked toward creating what King called the "beloved community."

The black church served as the center for the Civil Rights Movement in the South in both logistical and symbolic ways. It offered a central meeting place, a community bulletin board, and a cadre of respected community leaders. It also served as a model of the kind of independence that African Americans sought, for the black church existed (for the most part) beyond the grasp of the white power structure. In addition, biblical stories provided symbols and metaphors for the freedom struggle, and traditional hymns and gospel songs were easily adapted into the "Freedom Songs" that provided the Movement with great spiritual energy.

Though the language and ideals of the Civil Rights Movement drew primarily from Christianity, there was much in it that appealed to people of other faiths and backgrounds. Both the idea that God was on the side of oppressed people and the explicit linking of civil rights activism to the prophetic tradition resonated with Jews. For some Jews, the religious language of the Civil Rights Movement connected directly to their experience of Judaism; for others, who did not identify as religious, the Civil Rights Movement became a religion of its own.

Liberal institutions within the organized Jewish community also played explicit roles in the Civil Rights Movement. Both the Reform Movement and the Conservative Movement invited Martin Luther King, Jr. to speak at their national meetings. The Reform Movement had publicly supported civil rights since the beginning of the 20th century, first coming out against lynching in 1899 and passing resolutions throughout the 1950s and 1960s (and beyond) asserting their commitment to civil rights and racial justice. Prominent rabbis of both movements were public civil rights activists, speaking out to their congregations, marching with King, and getting arrested at demonstrations (sometimes to the disapproval of their congregants and/or denominational leadership). Among the most famous was Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel in the Conservative Movement, whose photo marching arm in arm with King in Selma in 1965 has become an iconic image of Jewish civil rights activism, and whose description of that march as "praying with my legs" is often quoted by Jewish activists. (For information about the Jewish presence at the March on Washington, see the introductory essay for that lesson.)

Civil Rights activism was often more complicated for rabbis in the South than for their northern counterparts. Southern rabbis generally supported racial equality in principle, but were concerned about the practical implications of taking a public stand against segregation and for civil rights. A rabbi's public support of civil rights strengthened the segregationists' claim that Jews threatened the southern way of life, and could put the Jewish community in economic and physical danger (in several communities, Jewish businesses were boycotted and synagogues were bombed). The social position of Jews in the south was precarious – Jews were often accepted as part of the social fabric, and in many cities were prominent business people who often ran local stores, but they were also seen as different from other whites and somewhat suspect. They had to work hard to fit in, and many Jews were reluctant to take action that would set them apart from the other white community leaders. They felt they needed to assure their own equality and security first.

Southern rabbis did not often engage in mass civil rights protest, but they did educate their communities and quietly encourage them to consider their role in promoting tolerance and equality. Some took individual action, and as a result faced violent retaliation as well as social isolation. Rabbi Perry Nussbaum of Jackson, MS, for example, survived the bombing of his synagogue and his home, as well as an attempt at his removal by some of his own congregants. Many congregations tried to prevent rabbis from taking public stances on civil rights issues; the synagogue in Hattiesburg forced out two rabbis within two years. Other rabbis were committed to aligning with the positions of their congregants and preserving their safety. In speaking about other southern rabbis who were involved in the Civil Rights Movement, Rabbi Moses Landau of Cleveland, Mississippi said, "It is your privilege [as a rabbi] to be a martyr…There are dozens of vacant pulpits. You can pick yourself up within 24 hours and leave. Can you say the same of the about 1000 Jewish families in the state? I am paid by my Congregation, and as long as I eat their bread I shall not do anything that might harm any member of my Congregation without their consent." (Quotation from interview conducted by Allen Krause, "The Southern Rabbi and Civil Rights," unpublished paper, 1967, Civil Rights, Box no. 1747, American Jewish Archives, p. 292.)

Southern rabbis who did participate found it easier to get involved in civil rights activism when joined by Christian clergy in their community, as this made their own activism less noticeable and less likely to attract anti-Semitic response.

Many southern rabbis did not welcome the civil rights activism of their fellow rabbis in the North and they resented northern self-righteousness around civil rights issues. They saw these rabbis as having the luxury of taking political stands that would not impact their own lives or their congregations. Those who came south to protest would soon go back to their lives in the North, while their co-religionists in the south would bear the brunt of the anti-Semitic sentiments they had provoked. Southern rabbis encouraged their northern counterparts to speak from their own pulpits rather than get involved in communities that were not their own, where they didn't know the subtleties and could harm the position of other Jews.

The case of Rabbi Milton Grafman of Birmingham's Temple Emanu-El illustrates the challenges southern rabbis faced and their ambivalence about how to relate to the Civil Rights Movement. In the 1950s, Grafman upheld a position of neutrality, prioritizing the safety of the Jewish community above all else and arguing that segregation was a "Christian problem" between whites and blacks. In April 1963, when King and the SCLC began a direct action campaign against Birmingham businesses, Grafman was one of eight local clergy who wrote a public statement criticizing King for the timing of the demonstrations, which came just as white moderates had been working on a referendum election that would improve race relations. These moderates felt that local citizens could best solve their own problems, and that the SCLC should not get involved before the newly elected leadership had a chance to make changes. King responded from prison in his famous "Letter from a Birmingham City Jail," condemning these white liberals as too cautious and insufficiently responsive to black suffering; in a comment that seemed to target Grafman explicitly, King said that if he had lived in Hitler's Germany he would have put himself at risk to help Jews.

Grafman's reputation suffered as a result of this incident, and many civil rights supporters viewed him as a coward and a racist. However, this perspective does not accurately capture Grafman's role. In 1963, Grafman also signed a letter written by other white clergy protesting Governor Wallace's defense of segregation. After the April demonstrations ended, Grafman played a role in helping to ease the transition to integration in Birmingham. And only a few months later, in September 1963, he delivered a heated Rosh Hashanah sermon to his own congregation, condemning them all for not doing more to fight the evils of racism in their community.

Though quick to be judged, rabbis during the Civil Rights Movement were often in a difficult position of competing priorities and conflicting responsibilities. As public figures with influence over their congregants and a pulpit from which to preach, clergy are often expected to be social justice leaders; as spiritual leaders who help connect their communities to God, they are often held to a higher moral standard. Yet what they consider to be their ultimate moral responsibility – whether it is to God, to the security of their congregants, to justice in the larger community – may shift over time and in relationship to their specific congregations and communities.

Introduction: Rabbi Milton Grafman Sermon

- Explain to your class that while the Civil Rights Movement was a social movement to change American laws and behaviors, it began in churches, and involved many Christian and Jewish clergy in addition to politicians, students, and other "ordinary people" without public roles. Today, we will learn about a number of Jewish clergy who participated in the Civil Rights Movement, and examine their reasons for getting involved, their level of involvement, and whether we think it was appropriate for them to be involved as clergy rather than just as American citizens.

- Distribute copies of the Rabbi Milton Grafman Sermon to each student. Have your students follow along on their copy as they listen to the audio recording of Rabbi Grafman giving his sermon.

- Play portions of the audio recording of Rabbi Grafman's sermon. Be sure to test the volume level before class. (Sermon is 38:54 minutes.)

- Use the questions on Rabbi Grafman's sermon to generate class discussion.

- When you are finished discussing Rabbi Grafman's sermon, explain to your students that now they are going to have a chance to learn about some other Jewish clergy and their involvement in the Civil Rights Movement on their own.

Document Study: Jewish Clergy in the Civil Rights Movement

- Divide your class into four groups. [Note to teacher: If you have a small class, you may want to choose just a few of the documents included with the lesson rather than using them all.]

- Provide each group with a different Document Study from the following list:

- Have each group read about the rabbi(s) they've been assigned and discuss the questions on their study guide. You may want to walk around the classroom, checking in with each group to make sure they understand terms and to see how they are progressing.

- When each group is done studying its document, explain to your class that during the Civil Rights Movement individuals and groups often carried banners that identified them and/or stated their goals. Since each group today has studied a different document representing different rabbis, each group is going to design a banner that will represent their rabbi(s), the rabbi(s)' role in the Civil Rights Movement, and their reasons for getting involved. The groups may want to include drawings, quotes or slogans, and/or symbolic representations to help get their messages across. When the banners are done, each group will be asked to bring their banner to the front of the classroom and give a brief explanation.

- Distribute mural paper and art supplies to each group. Allow the groups enough time to create their banners.

- When the groups have completed their banners, invite one group at a time to come to the front of the classroom and display its banner. (You can encourage groups to walk behind their banner as they come up to the front of the room, for extra effect.) Have a few members of the group share with the class the name of the rabbi(s) they studied and explain what they put in their banner. You may want to fill-in or expand upon any important points for the class to know.

- If there is time, and you have arranged for it ahead of time, you may want to have your students march to another classroom (possibly that of a younger grade) with their banners and have them teach the students a little of what they have learned.

Discussion: What is the Role of a Rabbi?

- Have a wrap-up discussion with your class using the following questions:

- How would you describe to someone who is not Jewish what a rabbi does? (You may want to write their descriptions on the chalk board, white board, or chart paper, or invite students to do so.)

- How, if at all, did the rabbis we studied today go beyond this definition? (or differ from it). Give examples of specific rabbis that support your argument.

- What types of roles did the rabbis we studied today play in the Civil Rights Movement?

- From what you read, what do you think were the experiences and values that most influenced these rabbis?

- Do you think it is appropriate for a rabbi to participate in political/social demonstrations as a clergyperson? (If students give conditional answers, or all pick one side, encourage students to explain when they think it is ok, and when they think it is not ok. Or you can encourage students to talk more generally now, and go into specifics with the subsequent questions.) What about participating as a more anonymous individual? What would the difference be? Why?

- On what current political/social issues would you want to see your rabbi take a stand? What type of involvement do you think would be most appropriate?

- On what current political/social issues would you not want to see your rabbi take a stand? Why not?

OPTIONAL ACTIVITY: Clergy Interview

- Invite a member of the Jewish or Christian clergy (working or retired) in your community to speak to your class about his/her involvement in the Civil Rights Movement or another social justice project. Ask the clergyperson to focus on the reasons for his/her involvement (both personal and religious), the way in which he/she participated, the response of his/her congregation, and his/her thoughts on what role clergy should

play in social justice issues (particularly divisive ones). You also may want

to ask the clergyperson to answer the question: “What do you see as the civil

rights issues of today?” This activity can be done at the beginning of the lesson as an introduction to the topic or at the end of class as a final wrap-up activity.

- Introduce the clergy person to your class and explain the reason for his/her visit.

- Give the clergyperson 15-20 minutes to speak to your class.

- Give the students sufficient opportunity to ask questions and hear responses.

Rabbi Milton Grafman Sermon

Milton Grafman (1907-1988)

Born in Washington, and ordained at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in 1931, Milton Grafman spent most of his career as the rabbi of Temple Emanu-El in Birmingham, AL. Like many southern rabbis, Milton Grafman found himself caught between the realities of southern Jewish life and civil rights activists. While he and other clergy worked for the integration of public parks, thus angering many white southerners, he also believed that civil rights activists, especially Jewish ones, wanted to change things too quickly and did not understand the realities of southern life or the position of southern Jews.1

In 1963, civil rights activists began a large-scale protest of segregation in Birmingham. Faced with an injunction to stop the protest, Martin Luther King announced he would march on City Hall. Many feared widespread violence. Rabbi Grafman and eight other members of the clergy met to share their concerns, angered by King's insistence on protesting before the recently elected mayor had a chance to pass desegregation legislation. They wrote a letter, published the next day in Birmingham's newspapers, in which they essentially asked King to wait and give the moderate government a chance. Despite the letter, the protests continued.

On April 16, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote his famous "Letter from a Birmingham Jail." Addressed to the local white clergy who had been critical of King's tactics, the letter expressed King's disappointment with their inaction.2

In September of the same year, Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed, killing several African American children. The bombing occurred on Sunday, September 16, and the funeral for the children was held on Tuesday. Rosh Hashana began that same Tuesday evening. In his sermon on Rosh Hashana morning, Rabbi Grafman expressed his horror at the violence and loss and asserted that white citizens in Birmingham – Jews and Christians together – needed to help make things right.

Sermon by Rabbi Milton Grafman, September 19, 1963

Rabbi Milton Grafman found himself caught between the realities of southern Jewish life and civil rights activists. In 1963, Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church was bombed, killing several African American children. Rosh Hashana began that same Tuesday evening. In his sermon on Rosh Hashana morning, Rabbi Grafman expressed his horror at the violence and asserted that white citizens in Birmingham needed to help make things right.

Courtesy of the American Jewish Archives

Discussion Questions

- Review: Who gave this sermon? When? Where?

- How do you think the way it was communicated might have influenced the message?

- Who was the intended audience? How do you think that might have influenced the message?

- Rabbi Grafman repeats several times that he is sick at heart. What do you think he means by this exactly? What seems to have caused him to feel this way?

- In what ways has Rabbi Grafman supported the Civil Rights Movement? In what ways has he not? What does he suggest he has always been mindful of in making his decisions about whether or not to act?

- What is Rabbi Grafman calling on his congregants to do? Why does he think they need to do this?

- How does Rabbi Grafman think change will come about in Birmingham? How do you think this differs from how civil rights activists want to bring about change?

- How do you think Rabbi Grafman's and his congregation's relationship to the Civil Rights Movement is complicated by the fact that they live in the South?

- What do you think Rabbi Grafman believes is his appropriate role in the Civil Rights Movement? What evidence do you have for this? Do you agree or disagree with this view of the role of a rabbi?

- Are there any current political/social issues on which you think rabbis today should take a stand? What kind of role would you want to see them take?

Abraham Joshua Heschel

Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907-1972)

Born in Warsaw into a Hasidic dynasty in 1907, Abraham Joshua Heschel was ordained in Europe. He also pursued a secular education, but was unable to finish his doctorate in Germany because of anti-Semitism. After Adolf Hitler came to power and began his campaign against the Jews, many rabbinic seminaries in America invited European rabbis to teach at their schools. In this way, Abraham Joshua Heschel came to Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of America (the Reform movement's seminary) in 1940. Later, he moved to the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary, feeling that this was a better fit with his traditional Jewish background and views.

Abraham Joshua Heschel is considered to be one of the great theologians of the twentieth century. He wrote on many Jewish topics including the Prophets. Heschel's experience during the Holocaust and his study of the Jewish prophets influenced his belief that Judaism required of one both deeds and actions. Known as "Father Abraham" to many of Martin Luther King's followers, Abraham Joshua Heschel was an outspoken activist for civil rights who marched with King, met with John F. Kennedy about civil rights legislation, and is celebrated by many in the Jewish community for his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement and other movements for social justice. His reflection on participating in the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in March, 1965 -- "I felt my legs were praying" -- has become a model of activism as religious practice.

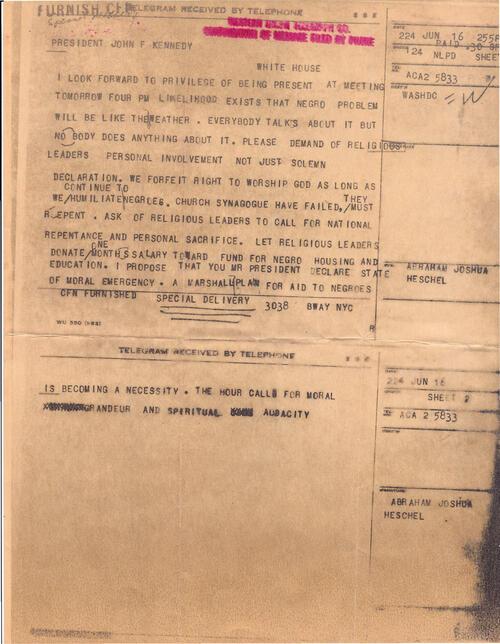

Telegram from Abraham Joshua Heschel to President John F. Kennedy, June 16, 1963

Telegram from Abraham Joshua Heschel to President John F. Kennedy, June 16, 1963.

Published in Moral grandeur and spiritual audacity: essays, ed. Susannah Heschel (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1996), vii.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel on the Selma March, March 21, 1965

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marching with other civil rights leaders from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, on March 21, 1965. From far left: John Lewis, an unidentified nun, Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King, Jr., Ralph Bunche, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth.

Discussion Questions

Part I

- Initial assessment: Who wrote this telegram? When was it written? What was the context for writing the telegram?

- How do you think the format (a telegram) might have influenced the message?

- Who was his specific audience? What larger audience might this telegram also have been meant for?

- In the first half of the telegram, Heschel asks the president to make some demands of religious leaders. Let's recap: What are these demands? Why does Heschel think this is necessary? Your interpretation: What do you think of a religious leader asking the President of the United States (a secular leader) to make religious demands of religious leaders?

- In the second half of the telegram, Heschel makes certain proposals to the President. What are these proposals? Your interpretation: How do they blend religious issues and political issues?

- Heschel says that "We forfeit the right to worship God as long as we continue to humiliate Negroes." What do you think he meant by this? Do you agree? Do you think worshipping God is a right that we earn through our actions? If so, what do you think are the kinds of actions that might forfeit this right?

- What do you think Abraham Joshua Heschel meant when he said "The hour calls for high moral grandeur and spiritual audacity?" What do those words mean to you?

- What do you think the purpose of this telegram is?

Part II

- How do you think Abraham Joshua Heschel's experience and/or Jewish values influence his participation in the Civil Rights Movement? What in the telegram makes you say that?

- Do you think this is an appropriate role for a rabbi? Why or why not?

- Are there any current political/social issues on which you think rabbis today should take a stand? What kind of role would you want to see them take?

Rabbis Who Marched in Alabama

Background

The newspaper article in this Document Study comes from Rabbi William G. Braude's personal papers, and brief biographies of Rabbi Braude and other Rabbis involved in the incident are included.

William G. Braude (1907-1988)

Born in Lithuania in 1907, William Braude came to America with his parents in 1920. In 1931, he was ordained at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the Reform movement's seminary. His first and only pulpit was at Temple Beth-El in Providence, RI, where he worked on behalf of African Americans even before the formal beginning of the Civil Rights Movement and continued his involvement as a supporter of Martin Luther King, Jr. However, he did not support all civil rights legislation. In this he differed from many of his congregants who disagreed with his conservative politics.

Saul Leeman

Ordained at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the rabbinic school of the Conservative movement, Saul Leeman had a pulpit at the Cranston Jewish Center in Cranston, RI (now Temple Torat Yisrael) during the 1960s.

Nathan Rosen

Nathan Rosen's first pulpit was in Savannah, GA, where he learned about Jim Crow laws and the degradation of America's African American community first hand. By the 1960s, Rabbi Rosen was the director of the Hillel Foundation at Brown University, in Providence RI.

Southern Hospitality Was Not Extended Say R.I. Rabbis Who Marched in Alabama

Rabbis March in Alabama, April 2, 1965, Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2: Newspaper article describing how unwelcome the Rabbis felt by white southerners when they went to march in Alabama."Southern Hospitality Was Not Extended Say R.I. Rabbis Who Marched in Alabama," Rhode Island Herald, 2 April, 1965, 1,8.

Courtesy of The Voice & Herald of Rhode Island

Rabbis March in Alabama, April 2, 1965, Page 2 of 2

Page 1 of 2: Newspaper article describing how unwelcome the Rabbis felt by white southerners when they went to march in Alabama."Southern Hospitality Was Not Extended Say R.I. Rabbis Who Marched in Alabama," Rhode Island Herald, 2 April, 1965, 1,8.

Courtesy of The Voice & Herald of Rhode Island

Discussion Questions

Part I

- Initial assessment: Who wrote this article? When?

- In what context was it written?

- Who was the intended audience for this document? How do you think this influenced the message of the article and/or what the rabbis told the interviewer?

- What did Rabbis Braude, Leeman, and Rosen do, according to this article?

- According to this article, why did these rabbis choose to march in Alabama? What other reasons do you think might have influenced their decision?

- According to this article, what kind of reception did these rabbis receive from people in Alabama? How did this reflect the feelings of the different groups whom they met?

- Did they feel that the march was effective? Why?

- How did the rabbis build on their experience by bringing it to the attention of others?

Part II

- How do you think these rabbis' experience and/or Jewish values influence their participation in the Civil Rights Movement? What clues from the article make you think that?

- How would you describe the role that these rabbis played in the Civil Rights Movement?

- Do you think this is an appropriate role for a rabbi? Why or why not?

- Are there any current political/social issues on which you think rabbis today should take a stand? What kind of role would you want to see them take?

Letter from the Rabbis Arrested in St. Augustine

Michael Robinson (1924-2006)

Born and raised in Asheville, NC, Michael Robinson was familiar with the inequalities between blacks and whites in the South, but he also learned that it didn't have to be this way. Robinson's father was an optometrist who treated black and white patients in the same office. When he was 10 years old, his "colored mammy" (an African American woman who worked as a servant, often helping to raise a white family's children) was forced to sit on the back of the bus and young Robinson chose to sit with her even though he was breaking the law and local custom.

Michael Robinson got involved in the Civil Rights Movement in the late 40s and early 50s, while a rabbinic student at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the Reform movement's seminary. During that time, he organized a group of fellow students to try and desegregate a Greek restaurant in Cincinnati. After ordination, Robinson took a pulpit in Croton, NY, a suburb of New York City. During the summer of 1964, Rabbi Robinson, along with a number of other Reform rabbis who had been attending the Central Conference of American Rabbis conference, answered Martin Luther King's call to join him in St. Augustine, FL. Once there, he was arrested, along with 15 other rabbis, for participating in civil rights activities.

Why We Went: A Joint Letter from the Rabbis Arrested in St. Augustine

"Why We Went: A Joint Letter from the Rabbis Arrested in St. Augustine," June 19, 1964, page 1 of 3

"Why We Went: A Joint Letter from the Rabbis Arrested in St. Augustine," June 19, 1964, page 1 of 3.

Courtesy of Dr. Eugene Borowitz.

"Why We Went: A Joint Letter from the Rabbis Arrested in St. Augustine," June 19, 1964, page 2 of 3

"Why We Went: A Joint Letter from the Rabbis Arrested in St. Augustine," June 19, 1964, page 2 of 3.

Courtesy of Dr. Eugene Borowitz.

Discussion Questions

Part I

- Initial assessment: Who wrote this document? When?

- Where was it written?

- Who do you think the intended audience was? How do you think this might have influenced the message?

- What did the rabbis who wrote this letter do to get arrested?

- In their letter, the rabbis say that "We came because we could not stand silently by our brother's blood." This quote is based on Leviticus 19:15-16 which says, "You shall not render an unfair decision: do not favor the poor or show deference to the rich; judge your kinsman fairly. Do not deal basely with your countrymen. Do not stand on the blood of your neighbor." It is part of the Torah portion known as kiddushim, or the holiness code, which is read during the High Holy Days.

What do you think the biblical quote means? What do you think the rabbis in St. Augustine meant by this quote? Why do you think they chose to use a biblical reference? - What do you think are some of the reasons these rabbis chose to participate in civil rights activities in St. Augustine? What in the letter makes you say that? Which of their reasons were based in Judaism? Which were universal? Which were particular to being a rabbi/Jewish leader?

- What part do you think community played in their experience before their arrest and during their time in prison?

- What did the rabbis feel they had accomplished by their actions in St. Augustine?

- What impact did the rabbis' actions have on them personally? In thinking about the reasons for and impact of activism, how would you rate the ways in which it changes the activist?

Part II

- How do you think these rabbis' experience and/or Jewish values influenced their participation in the Civil Rights Movement? What clues from the letter make you think that?

- How would you describe the role that these rabbis played in the Civil Rights Movement?

- Do you think this is an appropriate role for a rabbi? Why or why not?

- Are there any current political/social issues on which you think rabbis today should take a stand? What kind of role would you want to see them take?

Sermon by Rabbi James Wax

James Wax

Ordained at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion in the 1930s, James Wax served as the rabbi of Temple Israel in Memphis, TN, in the 1960s. Rabbi Wax supported racial justice, and during this period was a member of the Memphis Committee on Community Relations which worked towards integration. He also played an important role in resolving the sanitation workers' strike, which dragged on for many months, beginning in February 1968. Rabbi Wax knew Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb, who had at one time been a member of his congregation, and spoke to Loeb alone and with other delegates on several occasions to negotiate an end to the strike. After Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated while in Memphis supporting the sanitation workers' strike, Wax helped to arrange for the secret payment to the state of the funds necessary to pay the salary increases for the sanitation workers. Just days after King's assassination, Rabbi Wax shared his views of King with his congregation in a sermon.

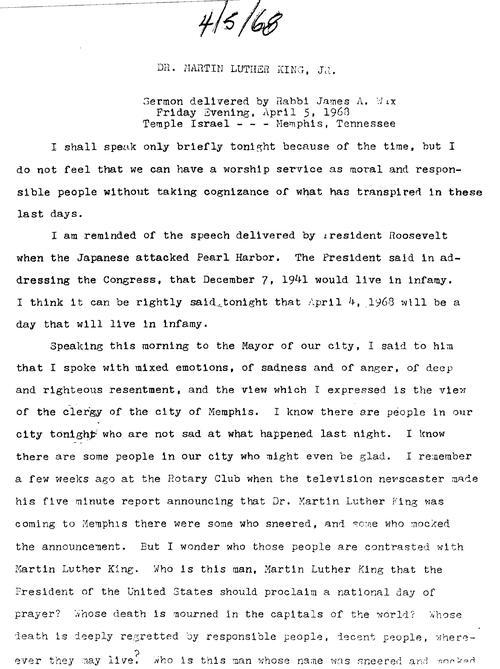

Rabbi Wax Sermon on Martin Luther King, Jr., April 5, 1968

Rabbi James Wax's Sermon on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 1968, Page 1

Page 1 of 4: Rabbi James Wax, "Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr." Sermon delivered at Temple Israel, Memphis, TN on April 5, 1968. Courtesy of Rabbi James Wax, Board of Trustees, and Archivist of Temple Israel, Memphis TN.

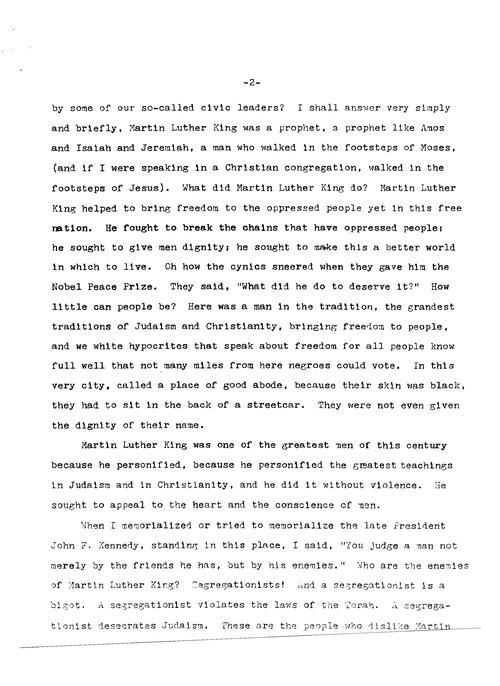

Rabbi James Wax's Sermon on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 1968, Page 2

Page 2 of 4: Rabbi James Wax, "Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr." Sermon delivered at Temple Israel, Memphis, TN on April 5, 1968. Courtesy of Rabbi James Wax, Board of Trustees, and Archivist of Temple Israel, Memphis TN.

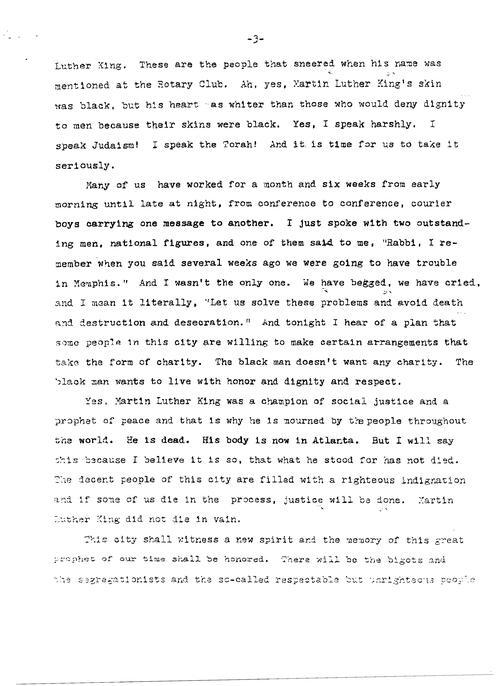

Rabbi James Wax's Sermon on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 1968, Page 3

Page 3 of 4: Rabbi James Wax, "Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr." Sermon delivered at Temple Israel, Memphis, TN on April 5, 1968. Courtesy of Rabbi James Wax, Board of Trustees, and Archivist of Temple Israel, Memphis TN.

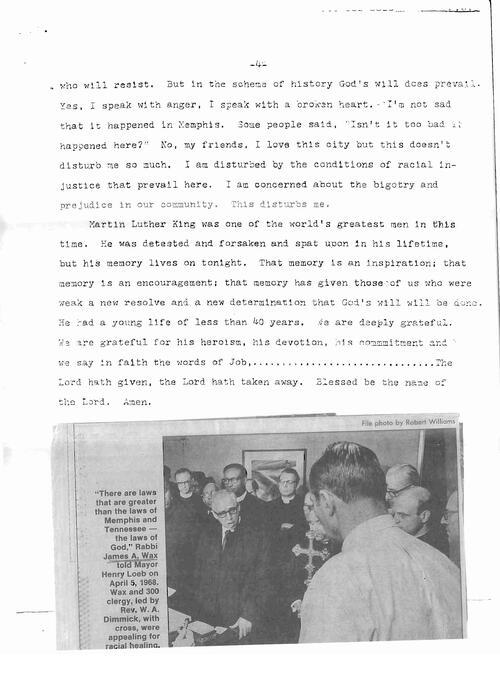

Rabbi James Wax's Sermon on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., 1968, with Newspaper Clipping, Page 4

Page 4 of 4: Rabbi James Wax, "Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr." Sermon delivered at Temple Israel, Memphis, TN on April 5, 1968. Courtesy of Rabbi James Wax, Board of Trustees, and Archivist of Temple Israel, Memphis TN. The newspaper clipping shows a photo of Wax.

Discussion Questions

Part I

- Initial assessment: Who delivered this sermon? When?

- How was it communicated? Where was it communicated? How do you think this might have influenced the message?

- Who was the intended audience? How do you think that might have influenced the message?

- How does Rabbi Wax view Martin Luther King, Jr.? What in his sermon makes you say that?

- How are these views similar and/or different from those of other people Wax mentions in his sermon?

- What, according to Rabbi Wax, is God's will?

- What do you think Rabbi Wax's purpose is in giving this sermon?

- Why do you think it might have been harder for Rabbi Wax to give this sermon in Memphis than it would have been for a Northern rabbi to give this sermon?

Part II

- How do you think James Wax's experience and/or Jewish values influence his participation in the Civil Rights Movement? What makes you say that?

- How would you describe the role that Rabbi Wax played in the Civil Rights Movement?

- Do you think this is an appropriate role for a rabbi? Why or why not?

- Are there any current political/social issues on which you think rabbis today should take a stand? What kind of role would you want to see them take?

CCAR

The Central Conference of American Rabbis is a professional organization for rabbis in the Reform movement. Its members, all graduates of Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, meet annually in different locations across the country.

Marshall Plan

An American economic plan named for U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall, who helped shape and implement it. This plan provided material and financial aid to help western European countries recover and rebuild after World War II. The plan was in effect for four years, by the end of which each country receiving aid was in better shape than before the war.

Union of American Hebrew Congregations

Currently known as the Union for Reform Judaism. It is an organization that provides services to and represents Reform congregations all across North America. Its affiliates include professional organizations for rabbis, cantors, Jewish educators, and temple administrators.

thank you for making this history available; unbelievable that 50 years later we are still struggling with being civil with and to one another.

Hello, I was doing a search for ethnic groups that marched during the Civil Rights Movement and saw a picture on Yahoo image which led to your site http://jwa.org/teach/livingthe.... On your site was a photo of marchers with signs in the background. I would like to seek permission to use this photos for a power point that I am doing for a 2014 power point that follows the 2013 power point that involves the March on Washington 1963. I thank you for reading my request and await your reply. Anthony

In reply to <p>Hello, I was doing a by Anthony Middleton

As the photo credit states, that image comes from the American Jewish Archives: Jacob Rader Marcus Center Hebrew Union College 3101 Clifton Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45220 Phone: (513) 221-1875 URL: http://www.huc.edu/aja/ You can contact them to obtain permission to use the photo.