Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman’s controversial beliefs made her many powerful enemies, yet she was never deterred from speaking on the variants of freedom encompassed in her anarchist vision. Suspicious of authority from an early age, Goldman committed herself to the anarchist cause after witnessing the unfair handling by the police and the courts of labor protests. As a writer, activist, and charismatic public speaker, she criticized institutions of all kinds for their abuse of power, arguing for worker’s rights, greater freedoms for women, and free love. Regularly arrested, harassed, and barred from speaking by the authorities, Goldman demonstrated that First Amendment rights often evaporated when one dared challenge the government. Her example prompted many to push for protections of free speech, eventually inspiring the creation of the ACLU.

When I was in America, I did not believe in the Jewish question removed from the whole social question. But since we visited some of the pogrom regions I have come to see that there is a Jewish question, especially in the Ukraine. … It is almost certain that the entire Jewish race will be wiped out should many more changes take place.

—Emma Goldman

Early life: immigration, domesticity, and discontentment

Emma Goldman was born on June 27, 1869, in the Jewish quarter of Kovno, Lithuania, to Abraham and Taube (Bienowitch) Goldman. She had two half-sisters, Helena and Lena, and two younger brothers, Herman and Morris. The antisemitism of czarist Russia propelled Goldman’s family to move to Königsberg, Prussia, and then to St. Petersburg in search of economic stability. These experiences of displacement, coupled with an aversion to the domesticity of women’s lives in the traditional Jewish family, drove Goldman to immigrate to New York at age sixteen. There she countered her father’s edict that “girls do not have to learn much! All a Jewish daughter needs to know is how to prepare gefilte fish, cut noodles fine and give the man plenty of children,” as she described in her autobiography, Living My Life. Inspired by the vision of political and personal freedom shared by the nihilist protagonists of Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s Russian novel What Is to Be Done?, Goldman hoped to find in America a new world of justice, freedom, and love.

Briefly swept up by the lure of self-chosen marriage and of secure work in the garment industry in Rochester, New York, Goldman soon realized the real promise of the New World was yet to be won. Her husband Jacob Kersner’s love of adventure proved illusory, and her own job paid too little for even the occasional luxury of a book or a flower. This personally discouraging early period of Goldman’s life in America coincided with an unusually dramatic series of events in the history of American labor. On May 1, 1886, 300,000 workers throughout the country went on strike for the eight-hour workday. On May 4, a bomb was thrown into a meeting in Chicago’s Haymarket Square, where laborers had gathered peacefully to protest recent police shootings of striking workers. Then, without conclusive evidence, anarchist organizers were blamed. In a trial that was a mockery of justice, the jury found the eight defendants guilty and sentenced seven to death. Inspired by the final words spoken by August Spies, Albert Parsons, George Engel, and Adolph Fischer, who ultimately were executed on November 11, 1887, Goldman was catapulted into action, certain that death could not silence the free voice of labor. She experienced this moment of transformation as her “spiritual birth.”

First forays into anarchism

Consciously drawing inspiration from her childhood hero, the biblical Judith who cut off the head of Holofernes to avenge the wrongs committed against the Jewish people, the twenty-year-old Goldman armed herself with a resolve to obliterate injustice. Infused with the desire to find expression for the messianic side of her nature, she left the year-long turmoil of her marriage and the provincial constraints of the small city of Rochester. On a hot summer day in 1889, sewing machine in hand, Goldman entered the vibrant culture of New York City’s Lower East Side to work and love in freedom.

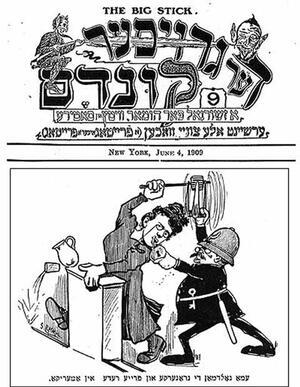

Various cafés and saloons served as evening meeting places for informal education and lively debate. Under the tutelage of Johann Most, the editor of the anarchist newspaper Die Freiheit [Freedom], the young Emma Goldman emerged as a precocious and impressive speaker. She lectured in German and Yiddish to immigrants anxious to improve the miserable working conditions and long hours that choked their lives.

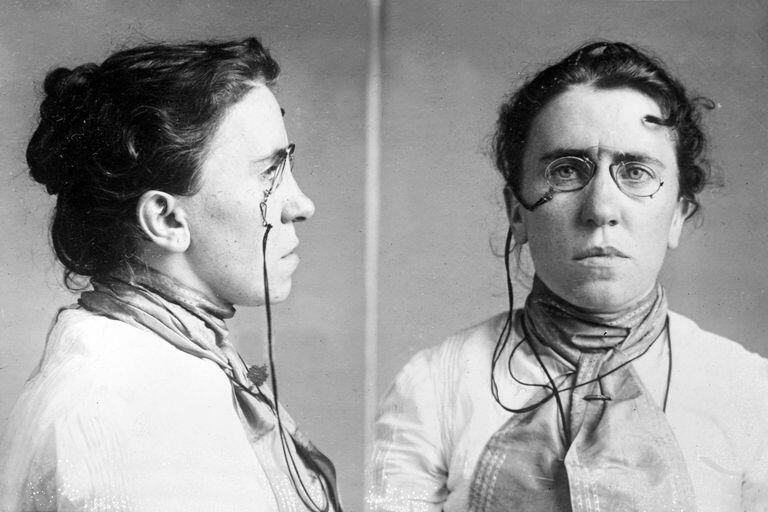

Emma Goldman's deportation portrait, 1919. In post-World War I America, foreigners and their "foreign ideas" were increasingly untolerated. Following her release from prison in 1919, Goldman was immediately re-arrested on the order of J. Edgar Hoover, then director of intelligence for the U.S. Justice Department. Hoover persuaded the courts to deny Goldman's citizenship claims, thus making her liable to deportation under the 1918 Alien Act, which allowed for the expulsion of any alien found to be an anarchist. On December 21, 1919, Goldman and 248 other foreign-born radicals were deported to the Soviet Union.

Courtesy of the Emma Goldman Papers, University of California, Berkeley.

Gradually she shifted from the singular focus on hardship and toil to what she articulated in her autobiography as “freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful radiant things.” She dared to advocate sexual and reproductive freedom when the dissemination of birth control information was punishable as obscene publication. As her range of concerns and notoriety grew, her audience swelled. Her ideas and flamboyant style, coupled with the fact that she was a woman in the spotlight, distinguished her from her more cautious male counterparts in the relatively exclusive circle of Yiddish lecturers.

Crossing the language barrier that had previously confined her influence to immigrant labor militants, her versatile command of English attracted receptive listeners among a growing liberal, bohemian, American-born constituency—in direct proportion to government and police attempts to suppress Goldman’s voice. Sentenced to a year in prison in 1893 for a speech at a demonstration of the unemployed, Goldman emerged proclaiming that government authorities “can never stop women from talking.” Undeterred by the threat of harsh consequences, she was determined to devote her life to teaching the principles of anarchism, and in the process to affirm the right to question authority. Perhaps her roots in the Jewish tradition that encouraged argument, debate, and refining the meaning of the weekly Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah reading fortified Goldman’s belief in the centrality of free expression.

And yet during this period, federal anti-anarchist laws made it increasingly impossible even to mention the word. Goldman was linked to a general fear of anarchists as provokers of violence. This fear was based primarily on the 1892 assassination attempt on steel magnate Henry Clay Frick by Goldman’s closest comrade, Alexander Berkman, and on the subsequent death of President William McKinley in 1901, shot by self-proclaimed anarchist Leon Czolgosz. The latter professed to having been inspired by Goldman. In part to counter the public’s distorted perception of anarchism as a philosophy of disorder rather than of harmony, Goldman helped found the 1903 Free Speech League.

Audience grows larger, enemies grow stronger

Never knowing whether a locked door or an arrest by the police would greet her at a lecture hall, Goldman dauntlessly continued to speak on the variants of freedom encompassed in her anarchist vision. Attracted by her quick wit and celebrity status, curious crowds rallied to support Goldman’s right of free expression, whether or not they believed in the specifics of her message. Roger Baldwin, civil libertarian and cofounder of the American Civil Liberties Union, attributed his political awakening to Emma Goldman and identified her courage as the primary inspiration for his work.

The ultimate gag order on Goldman’s ideas came when the United States entered World War I, and her anti-conscription lectures and organizing were considered a threat to national security. Eighteen months in federal prison was followed by a dramatic deportation in 1919 with Berkman and a boatload of other such undesirable immigrant radicals. Goldman returned to Russia and eventually to a protracted exile in Europe and Canada. Ironically, she could not escape the restrictions of political expression in Bolshevik Russia—especially for an anarchist. When the Kronstadt Rebellion was violently suppressed, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman left Russia in despair. She felt rejected by the public, not only by those to the left and right of her politics, but also by those who could not see beyond her Jewish ethnicity. Her relative freedom in Russia had been marred by lingering traces of antisemitism that persisted in England, France, and Canada, her most stable bases in exile. Only in Spain, where she worked as the English-language propagandist for the anarchist labor federation during the civil war, was she received as an international political figure commensurate with her self-image. Later, as the gloom of the Spanish defeat doused all optimism, the storm of Nazism grew, and Stalinism brutally entrenched itself, Goldman began to lecture on the interconnections between what she considered to be variant forms of totalitarianism.

Judaism and Goldman’s identity

Goldman wrote that her “life was linked with that of the race. Its spiritual heritage was mine, and its values were transmuted into my being. The eternal struggle of man was rooted within me” (Living My Life). She also noted that “social injustice is not confined to my own race, I had decided that there were too many heads for one Judith to cut off.” Goldman experienced political repression as systematic and not culture specific, and throughout her life, her complex and conflicted identity as a Jew remained a point of creative tension. Never escaping the public’s perception of her as a Jewish woman, with the ambivalent overlay the culture placed on the term, Goldman nonetheless preferred to think of herself as a woman who could transcend the boundaries imposed by the stereotypical social constructions of religion.

She distinguished cultural continuity from religious superstition and lectured widely on the “failure of Christianity”—false moralism and self-delusion. Goldman’s disbelief in God linked to her strong belief in anarchism and free love made her a vulnerable target in the fearful imagination of the religious mainstream of Christian and Jewish America. Concurrently, the liberal wings of both communities often offered Goldman their pulpit. To Rabbi Harry J. Stern of Temple Emanuel in Montreal, whom she admired for showing her that “one may serve his god and yet be true to man,” she wrote with the hope that her work would show him that “one can serve humanity without a god” (Goldman to Rabbi Harry J. Stern, March 1934).

Goldman had a strong Jewish cultural identity, but she was repelled by religious orthodoxy. In her circles, not a The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur went by without an organized picnic or ball sponsored by one of a number of “agitator groups,” including those involved with Goldman’s own publication, Mother Earth (1906–1917). On this holiest day of fasting and repentance, a newspaper reported that Goldman came dressed as a nun and cleared the dance floor for her rendition of “the anarchist slide.” Perhaps such yearly extravaganzas served as an atheist form of observance rather than as a dismissal of the Day of Atonement—a vehicle for solidifying a community of rebels against the rituals of their Jewish ancestors.

Another atypical form of cultural continuity may lie in Goldman’s affinity to anarchism as a philosophy of social organization antithetical to state politics, consistent with the popular pre-Holocaust conception of the Jewish people held together not by a Jewish state but by a shared belief system. The first volume of Goldman’s Mother Earth magazine (1906) included a critique of national atavism and asserted that “owing to a lack of a country of their own, [Jews have] developed, crystallized and idealized their cosmopolitan reasoning faculty ... working for the great moment when the earth will become the home for all, without distinction of ancestry or race” (Mother Earth, March 1906, 5). Later in life, Goldman was more defensive about her earlier dismissal of the movement for a Jewish homeland. In 1937, alarmed by the rise of Hitler, she wrote to a friend, “While I am neither a Zionist nor a Nationalist, I have worked for the rights of the Jews and [against] every attempt to hinder their life and development” (Emma Goldman to S. Gleiser, February 2, 1937). She wrote extensively on the rise of Nazism and on the ways in which Jewish culture had contributed to the richness of the Weimar Republic. Foreseeing the dangers that loomed over 1930s Europe, she began reluctantly to acknowledge that, if it were possible to respect the rights of the people of the host country, the need for a Jewish refuge was urgent.

Goldman’s legacy: the wandering Jew

Cast out for playing such a powerful role in the politics and culture of the periphery, Emma Goldman was forced to live the life of a wandering Jew—“A Woman Without a Country,” the title of one of her essays. Her longtime friend and attorney, Harry Weinberger, captured the essence of her life while lamenting her death in his funeral oration: “She spoke out in this country against war and conscription, and went to jail. She spoke out for political prisoners, and was deported. She spoke out in Russia against the despotism of Communism, and there was hardly a place where she could live” (Harry Weinberger, Funeral Oration, May 16, 1940). Through it all, the Jewish community was her hammock of support and formed the base of her first audiences in America and the core of her audience and support in later years. Sometimes spurned by the men who monopolized the Yiddish lecture circuit, it is Goldman’s voice that lives on and that ripples beyond her community of origin.

Emma Goldman died on May 14, 1940, in Toronto.

AJYB 42:479.

DAB 2.

EJ.

Falk, Candace et al., eds. Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years, Volume Two: Making Speech Free, 1902–1909 (2004).

Falk, Candace et al., eds. Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years, Volume One: Made for America, 1890–1901 (2003).

Falk, Candace, Stephen Cole, and Sally Thomas, eds. Emma Goldman: A Guide to Her Life and Documentary Sources (1995).

Falk, Candace, with Lyn Reese and Mary Agnes Dougherty. The Life and Times of Emma Goldman: A Curriculum for Middle and High School Students (1992).

Falk, Candace, Ronald J. Zboray, et al., eds. The Emma Goldman Papers: A Microfilm Edition (1990).

Glassgold, Peter, ed. Anarchy!—An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth. Washington D.C.: 2001.

NAW.

Obituary. NYTimes, May 14, 1940, 23:1.

UJE.

WWWIA 4.

Glassgold, Peter (ed.). Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s Mother Earth, Washington, D.C.: 2001.