Wuhsha the Broker

Although the documents of the Cairo Genizah rarely contain enough material on specific individuals for the scholar to build up a detailed portrait, one exception is Karima bat ‘Ammar (Amram) the banker, son of Ezra, from Alexandria. She is better known as “al-Wuhsha the Broker” (a name which could be translated as “Desirée” or “Untamed”), and she lived at the end of the eleventh century and into the twelfth. In a world where women were expected to be gainfully employed, Wuhsha is a prototype of the successful independent businesswoman, moving easily from the world of women into that of men.

A Successful Independent Businesswoman

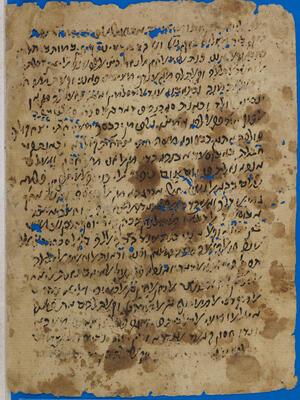

The documents of the Cairo [encyclopedia_glossary_term:313]Genizah[/encyclopedia_glossary_term] rarely contain enough material on specific individuals for the scholar to build up a detailed portrait. One exception is Karima bat ‘Ammar (Amram) the banker, son of Ezra; she is better known as “al-Wuhsha the Broker” (a name that could be translated as “Desirée” or “Untamed”). Wuhsha lived at the end of the eleventh century and into the twelfth.

In a world where women were expected to be gainfully employed, Wuhsha is a prototype of the successful independent businesswoman, moving easily from the world of women into that of men. Women worked at spinning and weaving in their homes in keeping with the segregated society and the practicality of such an arrangement; women brokers collected the finished products and sold them in the marketplace.

The Genizah documents, which list Wuhsha’s modest trousseau, include a detailed description of her jewelry. This jewelry may have served as the initial source of her investments, since in the Middle East a woman’s jewelry was her own property. Court records reflect Wuhsha’s growing wealth and her investments in merchandise from India as well as in caravan goods. As was typical among professional women, she also loaned money, retaining the collateral for the duration of the loan.

Marriage, Divorce, and an Affair

Wuhsha was briefly married to Arye ben Judah, by whom she had a daughter, Sitt-Ghazal. After their divorce she had a love affair with Hassun of Ashkelon and gave birth to a son, Abu Sa’d. The affair and birth are documented because Wuhsha went to court to prove that, although her son was the issue of an irregular relationship, it was not an adulterous or incestuous one, since otherwise he would not have been able to marry a Jew. Her friend, the [encyclopedia_glossary_term:327]hazzan[/encyclopedia_glossary_term]/court clerk Hillel ben Eli, advised her to obtain five [encyclopedia_glossary_term:347]kosher[/encyclopedia_glossary_term] witnesses attesting to the fact that she was alone in her apartment with Hassun, who may have tried to deny having a love affair. There is no evidence as to why Wuhsha and Hassun did not marry, but she may not have wanted to share her estate with him or he may already have had a wife in Ashkelon.

Hillel ben Eli, who wrote the document relating to Wuhsha’s affair, also wrote her will, which is one of the most informative documents about her. It lists her personal gifts, her communal gifts, and what she expected to leave to synagogues and charitable institutions. The main share was to go to her son Abu Sa’d, in part to pay for his religious education. The plans for her funeral are detailed and expensive, describing the coffin, her attire, the pallbearers, and the cantors. It is interesting to note that although the Iraqi synagogue (made up of Iraqi Jews who had moved to Egypt) ostracized her for her outrageous behavior, she forgave them and left money to them in her will, to be used for oil so that men could study there at night.

As eccentric as Wuhsha was, she is representative of Geniza women in multiple ways. Her marriage and divorce are evidence of women’s roles in the economy and their control over their wealth. Her social status determined her education. Her Jewish upbringing is reflected in her charitable giving and her desire to educate her son as well as legitimize him.

In a patrilineal society such as that of Cairo, Wuhsha was important enough to have both her daughter and granddaughter cite their connection to her in their own legal documents long after she died.

Goitein, S.D. “A Jewish Business Woman in the Eleventh Century.” The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Volume of the Jewish Quarterly Review, Philadelphia: 1967, 225–247; Ibid. A Mediterranean Society, Volume III. The Family. Berkeley and Los Angeles: 1978.

Cohen, Mark. Poverty and Charity in the Jewish Community of Medieval Egypt. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Goldberg, Jessica. Trade and Institutions in the Medieval Mediterranean: the Geniza Merchants and their Business World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.