Food in the United States

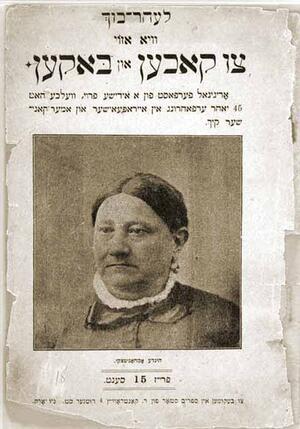

Hinde Amchanitzki's Lehr-bukh vi azoy tsu kokhen un baken (Textbook on How to Cook and Bake), published in New York, circa 1901, was one of the first Yiddish cookbooks published in the United States. Using her forty-five years of experience in European and American kitchens, Hinde Amchanitzki provided thousands of newly arrived Eastern European immigrants with an introduction to American cuisine, as well as recipes for traditional Jewish fare, in a language they could understand. In her introduction, the author (pictured on the cover) promises that using her recipes will prevent stomach aches and other food-related maladies in children.

Institution: U.S. Library of Congress, Hebraic Section.

Food and foodways—the cultural actions and processes that surround food, including not only what we eat, but when, where, why, how, and with whom—are a critically important area of documenting and deciphering the evolving experience of American Jewish women from the earliest days of immigration to the present. Food is a lens onto American Jewish women’s worlds of family, religion, identity, work, political action, entrepreneurship, and more as they have encountered the forces of assimilation, anti-Semitism, systemic racism, sexism, changing consumer economies, and the long women’s movement. By examining food “moments” throughout American history, we see Jewish women not only shaping their own Jewish lives and that of their communities, but actively impacting and changing American life and culture.

Foodways of the Early Ashkenazi Immigrants

While the earliest Jews in North America were Western Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic Jewish immigrants who came to early America by the 1650s from Brazil, Spain, and Portugal, as part of a long Jewish migration forced by the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, the first sizable American Jewish community consisted of Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants who came from Central Europe between the mid-1700s and the first decades of the 1800s. During this period, many single immigrant men became peddlers, selling goods from town to town until they could open stores of their own—a nearly universal Jewish experience. While on the road, observant Jewish peddlers carried Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher food with them, such as hard-boiled eggs, and honored the Sabbath whether they returned home or stayed at a farmer’s home for the duration of the holiday. By taking in Jewish peddlers and clerks as boarders, middle-class Jewish women in cities from Savannah, Georgia, to Newport, Rhode Island, developed food-related businesses that provided familiar tastes, language, and a religious atmosphere for newly arrived immigrants who were separated from their families in Europe.

Mercantile trade was central to Jewish life and buying and selling food was critical to this economy. From the eighteenth century through the early twentieth century, America Jewish women worked alongside their husbands, as widows, and as sole proprietors, as dry good merchants, grocers, innkeepers, food vendors, and entrepreneurs. Jewish women were also the keepers of the religious and culinary lives of their families. Mobility, adaptation, and pragmatism influenced their choices and their expressions of “domestic Judaism.” In the 1870s, Lavinia Minis of Savannah advised her family to “keep the Sabbath Holy,” to follow the laws of kashrut, and to participate in the rituals of A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover and other Jewish holidays. Lavinia wrote her husband Abram when he was away on business and traveling on the Sabbath, “I do not think that you will ever regret having kept the Sabbath holy, Abram dear, although it is not more than a right-minded man should do” (Ferris, 40.)

As merchants, traders, slave-owners, and even a small number of planters, American Jews in the South, but also in Northeastern trading sectors, largely supported slavery and the economy it made possible. White-generated wealth from rice and cotton contributed to the affluence of Jewish communities, too. In South Carolina, a traditional silver rice spoon owned by the Lazarus family served the grain that became known locally as Carolina Gold. The family’s cake knife and silver kiddush cup—for making a special blessing over wine—was likely used each Sabbath and on Jewish holidays. In the spring of 1862, when Union forces occupied New Orleans during the Civil War, Clara Solomon, the teenage daughter of a Confederate Jewish family wrote in her diary, “Our [Passover] motzoes are so miserably sour that I don’t think I have eaten a whole one…I expect before long we shall all starve” (Ashkenazi, 334). Across the country, Jewish women participated in war-time efforts, including “sanitary fairs” and the publication of synagogue and community cookbooks as fundraisers to support both Union and Confederate troops.

Eastern European Jewish Immigrants and Food

More than two-thirds of the millions of Jews in America today trace their roots to greater Poland, including parts of Austria and Hungary (Galicia), the Ukraine, Lithuania, and Russia. Between 1881 and 1921, the year of the first law restricting Jewish immigration, almost 2.5 million of these Eastern European Jews arrived in cities throughout the United States. All were looking for a new life; many were also hoping to hold onto their Orthodoxy, which included the dietary laws, while others rebelled against such traditions. American “Jewish food” came into its own with the arrival of this wave of Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many Polish and Russian dishes not considered Jewish in Europe, like herring in sour cream, rye bread, and borscht, became identified in the United States as Jewish.

Jewish immigrants came to the United States carrying with them their brass candlesticks, mortars and pestles, and pots and pans, as well as century-old recipes. Food historian Jane Ziegelman examines the fascinating culinary history of five immigrant families in this era in her book 97 Orchard Street, including two Jewish families, one German, one Lithuanian, who were among the hundreds of immigrant families living in the Lower East Side building now home to the Tenement Museum. In many instances whole Jewish communities were transplanted, including the rabbi and shohet [person officially licensed by rabbinic authority to slaughter meat in accordance with Jewish dietary laws]. They crowded into New York’s Lower East Side, Chicago’s West Side, Boston’s North End, South Philadelphia, and neighborhoods in other cities. At one time there were almost four thousand kosher butcher shops in New York City alone. The immigrants were generally successful in finding work and housing and became a part of a network of familiar social and cultural institutions, such as landsmanshaftn, the Jewish mutual aid societies that were formed by immigrants originating from the same villages, towns, and cities in Eastern Europe. A square block in an immigrant area in any American city would include overcrowded tenements, sweatshops, basement synagogues, saloons, and cafes. In the typical tenement, tiny apartments burst with large families, boarders, and little air.

Many immigrant families moved away from urban centers once they had the opportunity, such as Louis and Dora Himmelstein, who with assistance from the Jewish Agricultural Society, purchased land to start a dairy farm in Lebanon, Connecticut, in 1913. Three generations of the Himmelstein family have grown vegetables, raised chickens, cared for a dairy herd, and sold eggs and milk. The Himmelstein women were farmers, homemakers, and entrepreneurs.

Providing aid and educational resources to the new wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants was a major concern for the more assimilated Jewish women from coast to coast. The first national Jewish women’s organization, the National Council of Jewish Women, was founded in the fall of 1893 as an outgrowth of a national Jewish Women’s Congress. By 1900, the 7,080 members in fifty-five cities helped support the rights of women, mission and industrial schools for poor Jewish children, free baths in Kansas City and Denver, and, of course, cooking classes in the settlement houses.

In 1901 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Lizzie Black Kander published a pamphlet entitled The Settlement Cook Book: A Way to a Man’s Heart. Containing one hundred nonkosher German-Jewish and turn-of-the century American recipes, The Settlement Cook Book— pver forty editions have been printed—soon turned into one of the most successful American cookbooks ever published. The proceeds were used to help immigrants who came to the United States at the turn of the century, and, in later years, provided the seed money to build the Milwaukee Jewish Community Center. Coming when it did, the cookbook marked a watershed in assimilation as a project of Progressive era reform movements. In her book Hungering for America, which explores the Italian, Irish, and Jewish foodways of this “Age of Migration,” historian Hasia Diner reveals how both “memories of hunger” and the “realities of American plenty” shaped the ethnic identity of these new immigrants in America.

Kander, the daughter of German-Jewish pioneer farmers, was known as the Jane Addams of Milwaukee for her work on behalf of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. In 1896, she established the Milwaukee Jewish Mission, or settlement house, in quarters borrowed from two synagogues. By 1898, the mission had begun to sponsor cooking classes every Sunday for these immigrants. The mission women taught the girls, who ranged in age from thirteen to fifteen, “modern” American cooking skills influenced by the growing fields of domestic science and home economics. They learned to prepare such dishes as German kuchen, cranberry jelly, and waffles in the only Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher cooking school this side of New York, according to the Sentinel, a Milwaukee newspaper. Nutrition, housekeeping, sanitation, and menu planning were key lessons as well, shaped by racist notions of “purity” seen in the literal whitening of food in this era, such as bland white cream sauces added to boiled and roasted meats and fish. For example, at the Milwaukee Jewish mission, girls also learned to prepare potato soup, creamed cod, coddled eggs on toast, and plain puddings. Each girl would prepare her own dish, often with her mother, older sisters, or friends as spectators.

Although they were not schooled in “New World” cooking, the young pupils of the mission kitchen were better versed in the practices of The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut than their teachers, a problem that led to some uncomfortable moments. In 1901, the Sentinel wrote about the kashrut problems of the teacher, Miss Pattee, a graduate of the Boston Cooking School: “The other day the little tea table at which the children were to set the food they had been preparing was all in white except for a red bordered napkin laid on as a centerpiece. It gave a bit of color to the table and added to the decorative effect, but the red bordered napkin was ‘fleischig’ and it happened to be a ‘milchig’ lunch so it had to be removed before the meal could proceed. … Sometimes Miss Pattee forgets about the ‘kosher’ and mixes up the custard and the bouillon spoons, but there is always a small girl with large dark eyes and a wealth of coal black hair to point out the mistake.” These young girls knew how to make gefilte fish and to weave eight braids in their During the Temple period, the dough set aside to be given to the priests. In post-Temple times, a small piece of dough set aside and burnt. In common parlance, the braided loaves blessed and eaten on the Sabbath and Festivals.hallah.

Other organizations followed suit, and cookbooks were sponsored by Jewish women’s organizations nationwide. Like The Settlement Cook Book, these books often had a German slant, included shellfish, especially oysters, and featured many goose recipes as well as other American dishes such as chicken chow mein, often made from leftover chicken soup, and Saratoga chips, a turn-of-the-century potato chip. In September 1905, the Montefiore Lodge Ladies Hebrew Benevolent Association of Providence, Rhode Island, published the following in a newsletter: “It was voted that ‘this lodge publish and sell a cookbook of favorite recipes.’ Two separate committees were appointed, one for the cooking recipes and the other to solicit advertising.”

As Jewish immigrants adjusted to new American food habits, they quickly forgot some of the foods of their poverty, like krupnick, a cereal soup made from oatmeal, sometimes barley, potatoes, and fat. If a family could afford it, milk would be added to the krupnick. If not, it was called “soupr mit nisht” [supper with nothing]. Bagels, knishes, or herring wrapped in a newspaper would be taken back to the sweatshop, providing a poor substitute for the midday lunch they were used to in Eastern Europe.

The Development of Kosher Certification

To combat these changes and the rise of Reform Judaism in America, many Orthodox Jews clung to their old traditions, including kashrut. (The first kosher cookbook published in America, Jewish Cookery by Esther Levy, appeared in 1871.) It was not always easy. In 1881 in Denver, for example, Jews were unable to acquire kosher meat, so they either had to practice ritual slaughtering for themselves or eat no meat. Later, many of them would become Conservative Jews.

One Orthodox Jew, Rabbi Hyman Sharfman, went from Kennebunkport, Maine, to Corpus Christi, Texas, in a gearless cycle car, sometimes on horseback, kashering meat and teaching people in the community how to do it themselves. Another, Dov Behr Manischewitz, hearing of the huge center of Reform Judaism in Cincinnati, decided to settle there as a shohet. He later made his fortune in the Unleavened bread traditionally eaten on Passover.mazzah industry.

The diverse Orthodox immigrant groups lacked unified Jewish leadership. In a small town in Russia, for example, the rabbi was the leader, and everyone went to the same shohet. In New York, with millions of people and thousands of kosher butchers, not to mention the importance of the separation between church and state, there was no central authority to whom to turn for validation of the religious laws. In 1888, eighteen Orthodox synagogues in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore organized themselves and brought over Jacob Joseph, the chief rabbi of Vilna, as their head. Among his other duties, he was supposed to organize the kosher meat business. Not surprisingly, considering what he was up against, he failed miserably. By 1917, at the height of Orthodoxy in America, there were a million Jews eating 156 million pounds of kosher meat annually—or at least meat they believed to be kosher. With no central authority, individual rabbis were putting hekhsher (kosher) stamps on the meat. Some was kosher, some was not. It was not until 1944 that a food inspection bureau to authenticate kosher meats was formed in New York State. It remains in operation to this day, and its inspectors regularly spot-check all kosher meat markets across the state—yet there are still occasional problems.

Because of escalating prices, kosher meat and bread riots broke out at the turn of the century with women leading the lines. One boycott was dubbed the “war of the women against the butchers.” The battle cry became “twelve cents instead of eighteen cents a pound.” Eastern European Jewish women oversaw the domestic consumption of their families and, as daily consumers in the marketplace, also controlled the pace of their families’ acculturation. Historian Andrew Heinze argues that Jewish women’s purchasing power of new mass-produced American food products and home goods—many designed specifically for a Jewish market and Jewish holidays—symbolized their changing status and place in the United States.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, the umbrella organization for Orthodox Jews, was established as a means of bringing cohesion to the fragmented immigrant Jewish populations. In 1923, the year it created its women’s branch and four years after women won the right to vote, the union’s official kashrut supervision and certification program was introduced.

At about that time, a New York advertising genius named Joseph Jacobs encouraged big companies to advertise their mainstream packaged products in the Yiddish press. Jacobs’s mission was to change the way Americans thought about Jewish dietary practices. The chains and the big food companies did not know how to promote to a Yiddish-speaking population, since they employed no Jews. Jacobs encouraged the Maxwell House coffee company to write a Haggadah and helped Crisco and Pillsbury to produce Yiddish-English cookbooks to teach the immigrant women, who would salivate over the illustrations in the Ladies’ Home Journal but could not read English. Now they could use Crisco to make an “American” apple or lemon meringue pie; better yet, they could serve their children southern fried chicken.

When canned products like H.J. Heinz Company’s baked beans and pork came on the market, an inventive man named Joshua C. Epstein, an Orthodox Jew, had a thought: What if Heinz made kosher vegetarian baked beans? Company officials liked Epstein’s suggestions, but they balked at the idea of writing “kosher” in Hebrew or English on the package. “Heinz wanted something identifiable, but not too Jewish: they didn’t want to antagonize the non-Jewish population,” recalls Abraham Butler, the son of Frank Butler, Heinz’s first mashgiah. With Jacobs and Rabbi Herbert Goldstein, one of the founders of the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations of America, the three devised the Orthodox Union OU symbol, today the best-recognized trademark of the some 120 symbols of kosher certification.

Sephardi and Mizrahi Cooking in America

From the 1880s to the 1920s, Eastern Sephardic Jews from Greece, Turkey, and the Balkans immigrated to the United States, pushed by growing political instability and the pull of economic opportunity. Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi Jewish immigrants from countries in the Middle East and North Africa arrived in this same era.

Food historian Claudia Roden aptly distinguishes the “cold world” of Ashkenazic cuisine—chicken fat, onion, garlic, root vegetables, and freshwater fish like carp and herring—and the “warm world” of Sephardic cuisine—eggplants and tomatoes, cracked wheat, rice, saltwater fish, and olive oil. Food writer Leah Koenig explains that unlike the Ashkenazi Jewish cuisine shaped by cold climates in Eastern and Central Europe, Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews brought the cuisine of countries shaped by a warm climate to America, with ingredients including more fresh produce, olive oil, spices, pine nuts, raisins, fish, and grains like couscous.

Sephardic Jews established lives and communities across America, including Georgia’s Congregation Or VeShalom in Atlanta (1914) and Etz Chayim in Montgomery, Alabama (1912). Fear surrounding the 1915 lynching and murder of Jewish industrialist Leo Frank in Georgia colored Sephardic Jews’ early years in American South. Regina Rousso Tourial recalled her father-in-law’s warning to his wife “not to dare go out of the house” during the Frank trial, an example of the racial radicalism and violence of this era fomented by the rise of white supremacy and anti-Semitism in the early twentieth century. The desire to stay among “their own kind” strengthened the retention of Sephardic cooking methods and recipes, which are reaffirmed each year at a Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day.Hanukkah-time food bazaar, an important fundraising event for Congregation Or VeShalom begun in the 1950s. Delicious Sephardic dishes and sweets continue to be made and sold by the women of the Sisterhood, including the popular bureka, a hand pie-shaped pastry filled with potato, spinach, rice, cheese, or eggplant and ground beef. Susanna Capelouto’s 2017 radio documentary, “Pie by Another Name: The Burekas of Or VeShalom” features the women of Or VeShalom speaking about their history and burekas.

Jewish Cooking in the South

In the Jewish South, skilled African American cooks and domestic workers, enslaved then free, deeply shaped evolving regional Jewish American cuisine. Black and Jewish culinary historian Michael Twitty argues that the first “kosher soul cookery” flourished in the coastal colonial South, where a culinary syncretism emerged between Black women cooks and Jewish women at the center of mercantile families. The dynamics of this labor and its racial interactions was complex, both exploitative and intimate.

In Greenville, Mississippi, where the nearest delicatessen is over 150 miles to the north in Memphis, Tennessee, the sisterhood members of Hebrew Union Congregation have organized a deli-style community meal for decades. The event raises funds for the historic congregation and allows non-Jewish neighbors to enjoy corned beef shipped in from Chicago piled high on rye bread for sandwiches. The annual deli lunch also reflects the Jewish self-sufficiency of places with small Jewish populations and little in the way of Jewish infrastructure other than a place of worship. Philip Graitcer shared this story through the voices of Hebrew Union’s resilient congregants in his 2017 radio documentary for the Southern Foodways Alliance, “Corned Beef Sandwiches in the Delta.”

Negotiating the rules of kashrut versus fitting into a largely non-Jewish community was clearly felt in Natchez, Mississippi, at Temple B’nai, founded in the 1840s. By the 1990s, the congregation had declined to just a few members due to the changing agricultural economy of the region. When the congregation celebrated its long history at a “homecoming” event in 1994, the tension of religion versus region still prevailed. Producer and journalist Robin Amer documented her grandmother Elaine Lehmann’s powerful voice—and presence—in this historic congregation in “The Last Jews of Natchez,” where listeners can learn about the “ham biscuit incident.”

Creating “Jewishness” Through Food

Scholars Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett [link to new entry on Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett] and Jenna Weissman Joselit describe a shift towards a sense of “Jewishness” and creating a “Jewish atmosphere” that American Jewish women experienced by the 1920s, much of which happened at home tables. By marking the Sabbath with a special Friday night family meal and other Jewish holidays with traditional foods, décor, and festive celebrations, wives and mothers could make their homes “a sanctuary” where Jewish identity and culture was reinforced, especially as synagogue attendance shifted in the suburbs.

Another site of kosher eating or kosher-style dining in this era was Jewish summer camps, evolving from sites of “Americanization” for the children of Eastern European immigrants and a natural respite for needy urban Jewish youth in the Northeast, to camps sponsored by Jewish political groups and organizations. Jewish boarding houses, resorts, and retreat centers in the mountains, the seaside, and rural venues allowed Jewish adults and children alike to experience Jewish community, engage in educational programs, and taste Jewishness at the table, for example, at festive Friday evening celebrations of the Sabbath meal and service. A weekly ritual at the Union for Reform Judaism’s Camp Henry S. Jacobs in Utica, Mississippi, is “Shabbat fried chicken.” Camp Blue Star, a family-owned, private, kosher Jewish camp was founded in 1948 in the western mountains of North Carolina, the same year as the founding of the state of Israel. Historian Jonathan Sarna says this crucial decade in Jewish camping was both an expression of cultural resistance after the Holocaust and an American promise to build and uphold the Jewish people.

The fast-growing influence of radio and television affected how Americans saw each other and how products were sold. The Goldbergs, a program about a fictional Bronx family, reached a radio audience of ten million in the 1930s and at least forty million two decades later on television. Just as I Remember Mama taught us about Scandinavians, The Goldbergs familiarized non-Jews with a loving, “everyday” Jewish family. Sometimes Molly Goldberg just cooked throughout the whole program, cutting up a chicken or chopping herring as the problems of her family paraded through her kitchen. In her 2009 documentary film “Yoo-hoo, Mrs. Goldberg,” filmmaker Aviva Kempner captures the talent and business acumen of television pioneer Gertrude Berg, who wrote, produced, and acted in this popular radio and television series.

After World War II another “cooking lady” stepped onto television. Her name was Edith Green, and her popular Your Home Kitchen ruled the airwaves in the San Francisco Bay area from 1949 to 1954. Although this “queen of the range” was Jewish, her cooking was American—and it was “gourmet.” A week’s recipes might include veal scallopini, coffee chocolate icebox cake, coconut pudding, or frozen tuna mold. She also showed her viewers how to use the new gadgets, such as electric mixers and electric can openers, that were the products of the postwar period of affluence.

Annual synagogue-sponsored Jewish food festivals or bazaars organized by congregational women’s groups became popular expressions of interfaith outreach in this era of American religious “brotherhood” as a welcoming way to introduce—and demystify—Jewish cuisine and Judaism to non-Jews. The Jewish Home Beautiful, a cookbook published by women of the Conservative movement in 1941, included scripts for holiday pageants and photographs of “model holiday tables” that could be staged for congregants and visitors alike. As innocent as these programs seemed at the time, these efforts reflected Jewish anxiety about their place in American society and postwar/post-Holocaust fears.

In the 1950s and 1960s, America reverberated with protest marches and lunch counter sit-ins led by young Black and white activists, including many Jewish youth, who demanded civil rights for Black Americans, including the right to vote. Twenty-three-year-old Carol Ruth Silver from Boston spent forty days in a Mississippi jail. In her diary, she described her surprise in enjoying the food prepared by experienced African American cooks: “June 8, 1961: My second prison meal, breakfast—at about 6 A.M.—was three more biscuits, some thin molasses syrup, grits and coffee. Aside from the grits, which I ignored studiously, I was almost embarrassed to pronounce it much to my liking. The coffee was black and sweet and not too strong, the biscuits were light and hot, and the syrup in which they were to be dipped was quite palatable” (Carol Ruth Silver, “The Diary of a Freedom Rider,” 7–8, 1961, Tougaloo Collection, Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson, MS). At the same time, a number of progressive Jewish women in Mississippi joined women-led interfaith and interracial teams who formed alliances, raised funds, and distributed supplies—including food—to civil rights programs and anti-poverty projects throughout the state.

Twentieth-Century Transformations

The matzah balls, gefilte fish, and even the Passover desserts American Jews eat today are certainly very different from those eaten in Europe or in the United States a century ago. Eastern European immigrants, many of them deeply interested in the way food was prepared, found great opportunities in the food business in cities across America. The butchers, bakers, and pushcart peddlers of herring and pickles soon became small-scale independent grocers, wine merchants, and wholesale meat, produce, and fruit providers. As it was in Europe with the religious, it was often the woman who ran the store as well as the family while the husband studied in the back. In urban Atlanta, the Feldman’s dry goods store catered to working-class African Americans. In many such businesses a kosher home existed upstairs, while downstairs customers found the seasonal greens and non-kosher cuts of pork and cans of lard they preferred.

Not only did Jewish immigrants go into the business of food, but they also adapted their Eastern European food ways to the new environment. Sunday, for example, a second day of rest, provided them with new gastronomic opportunities like a dairy brunch, an embellishment of their simple dairy dinners in Europe. Bagels, an afternoon snack food in Europe, became embellished with lox and cream cheese and eventually became an American icon. Writer and illustrator Ben Katchor examines the proliferation of new milchig eateries in America in his fascinating work The Dairy Restaurant. In Pastrami on Rye, historian Ted Merwin shares the history of the New York Jewish delicatessen as an iconic institution in both Jewish and American life.

In the early twentieth century, American Jewish witnessed great changes in food technology and scientific discovery that impacted their own kitchens. In Wisconsin, pioneer women like Lizzie Kander’s mother made their own yeast, corned their own beef, and prepared their own ketchups and pickles. Slowly the kitchen was transformed, liberating women from time-consuming chores. Not only was Heinz producing its bottled ketchups and fledgling companies making kosher canned foods, but companies were manufacturing a white vegetable substance resembling lard—the shortening that would change forever the way Jewish women cooked. Three years after Crisco was invented in 1910, Procter & Gamble was advertising that this totally vegetable shortening was a product for which the “Hebrew Race had been waiting 4,000 years.” Other inventions, too, like cream cheese, rennet, gelatin, junket, Jell-O, pasteurized milk, Coca-Cola, nondairy creamer, phyllo dough, and frozen foods would affect Jewish cooking in America.

With the growth of food companies, delicatessens, school lunch programs, and restaurants, American food and American Jewish food became more processed and more innovative. In 1925, the average American housewife made all her food at home. By 1965, seventy-five to ninety percent of the food she had used had undergone some sort of factory processing.

As the latest wave of Eastern European Jews became more Americanized, they began trying new dishes like macaroni and cheese and canned tuna casseroles. Jewish cookbooks included recipes for Creole dishes, for chicken fricassee using canned tomatoes, and for shortcut kuchen using baking powder. Many of these Jews cared little about the impact of scientific discoveries on kashrut. Others cared deeply.

Jews went into the packaged-food business, too. In a land of opportunity, some food merchants struck it rich. One Chicago baker named Charley Lubin made a luscious cheesecake; it was the beginning of the age of frozen foods, so he tried freezing his cake. It worked, and he named it Sara Lee, after his daughter.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, the first feminist A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seders were organized by leaders in the Jewish feminist movement in the United States, such as Bella Abzug, Phyllis Chesler, and Letty Cottin Pogrebin. These women-only events emphasized the myriad roles of women in both Jewish history and contemporary American Jewish life. In the 1980s, scholar and activist Susannah Heschel added an orange to the traditional, symbolic foods on the seder plate to represent the silenced voices of all marginalized peoples. The new ritual of Miriam’s Cup, a goblet of water included at seders to represent the absent voice of Moses’ sister in the Exodus story, began at a The new moon; the first day of the month; considered a minor holiday, especially for women.Rosh Hodesh event in Boston in 1989 (Levy, “Orange on the seder plate). After a long year of pandemic lockdowns in 2021 as she began to plan her Passover menu, writer Justine Orlovksy-Schnitzler noted the gendered dynamics that still place the pressures, necessary skills, and logistics of holiday preparation upon women (Orlovsky-Schnitzler, “Politics of Holiday Preparation”).

Into the Twenty-First Century

Over time, notions of “Jewish food” changed with the availability of regional ingredients across the country. Taste buds adjusted to local foods and flavors and evolving dietary guidelines. While Jews in Burlington, Vermont, ate potato latkes with maple syrup, Californians preferred theirs with local goat cheese. Gefilte fish was made with whitefish in the Midwest, walleye in Michigan, salmon in the Northwest, and haddock in Maine. Journalist Hanna Raskin notes that Jewish families in Charleston, South Carolina, adapted the recipe for their tables, since the traditional whitefish, carp, and pike weren’t typically shipped so far south. They created recipes using fish from low country waters. For years, Crosby’s Seafood Market in Charleston kept a file indicating exactly how much shad and how much sheepshead went into each household’s recipe for gefilte fish.

Another change notable at the beginning of the twenty-first century is the increasing number of Jewish women who have entered the food industry, specifically the kosher food business. The traditional male enclave of Empire Kosher Chickens and Gold’s Horseradish has now been joined by Lilly, Carol Ann, Aunt Gussie, My Mother’s Delicacies. An even greater change is the fact that many of these women are Orthodox. While Orthodox Jews own a disproportionate number of kosher firms, the women of this community were generally not encouraged to enter the business world. But now, a growing acceptance of women working outside the home has led to a growing trend of Orthodox women-owned food companies of varying sizes. At the 2004 Kosherfest in New York City, the annual trade fair of the industry, Orthodox women presented a range of products to their fellow tradespeople. Twenty percent of the booths represented businesses owned or operated by women, a significant increase over the fair’s earlier years.

Jewish women have now joined the race to satisfy the rising international appetite for kosher food (primarily among non-Jews, who consider “kosher” to be indicative of healthier, cleaner products), an $8 billion industry in the United States alone. Ironically, while many Jews have abandoned the rules of kashrut, non-Jews have begun to seek out kosher food.

While much of “Jewish food” has changed with the times, some women use food precisely as a way to memorialize the past. For generations of Jewish women, from survivors of the Holocaust and their descendants to thousands of individuals who trace their ancestral Jewish histories to other distant worlds, passing on their memories of the food (and life) they once knew by preparing lokshen kugel (noodle pudding), tzimmes (stewed carrots), mandelbrot (a strudel-like butter cookie), kreplach (dumplings), plov (a rice-and-meat pilaf), baba ganoush (a roasted eggplant spread), and burmuelos (a deep-fried pastry covered in honey syrup) provides their children and grandchildren with a “taste of the past” that reflects their cultural and geographic origins. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, Jewish immigrants from countries such as Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan have expanded the definition of American Jewish food, as has modern Israeli cuisine, from hummus and pita to shakshuka (a one-skillet vegetable and egg dish). Women food writers and chefs are powerful forces in America’s embrace of Israeli food as part of its Jewish foodways, including Joan Nathan, Israeli co-authors and chefs Einat Admony and Janna Gur, and American-born writer Adeena Sussman, who now lives in Tel Aviv. Drawing from their Israeli heritage, male chefs Yotam Ottolenghi in London and Alon Shaya in New Orleans have also anchored the flavors and dishes of the Middle East in the American Jewish kitchen and culinary canon. Shaya writes about the powerful influence of his safta (grandmother) Matilda in shaping his love of food.

In the foreword to Leah Koenig’s Modern Jewish Cooking: Recipes & Customs for Today’s Jewish Kitchen (2015), food writer Gabriella Gershenson writes, “Now may be the best moment in modern history to rediscover Jewish food.” She explains that “ethnic food” was once hidden by earlier generations of American Jews in the effort to assimilate and protect their families from prejudice and anti-Semitism, while a younger generation today is empowered by their cultural heritage, including cuisine. The vibrant worlds of Jewish foodways today—rising Jewish chefs and food purveyors, Jewish-focused restaurants committed to sustainable, seasonal, and local food sourcing, reinvented delicatessens, Jewish food journalism/cookbooks/media and digital platforms, food-related activism addressing hunger, food justice, the environment, food workers’ rights, animal welfare, Jewish farming initiatives, and Jewish food scholarship—all reflect the liberation of a new generation to redefine the meaning of American Jewish food and the important women’s voices at its helm, including queer, trans, gender-nonconforming, and cis womnx. The growth of this phenomenon as a new “Jewish Food Movement” began in the 1990s. (Marcie Cohen Ferris notes the groundbreaking publication of Joan Nathan’s award-winning book, Jewish Cooking in America, in 1994 and the 1998 PBS television series that followed as a pivotal moment in this movement. Nathan documented Jewish culture and history through the lens of food and gave American Jewish food a national platform as a regular columnist for the New York Times.)

The first two decades of the twenty-first century have witnessed a Gefilte Manifesto, the title of co-authors Liz Alpern and Jeffrey Yoskowitz’s 2016 book and call to American Jews to reclaim time-honored Jewish foods with fresh ingredients, brighter flavors, and less processed, packaged ingredients. In 2017 farmers and educators Shani Mink and SJ Seldin founded the Jewish Farmer Network, which recognizes the ancient agricultural history of the Jewish people while building a more just and regenerative food system for all. In the spring of 2021, journalist Tejal Rao described baker Emily Winston’s Boichik Bagels (founded 2019) in California as “some of the finest New York-style bagels I’ve ever tasted. They just happen to be made in Berkeley.” Religious studies scholar Adrienne Krone studies the Jewish community farm movement at the intersection of faith, Jewish ethics, agriculture, and environmental justice. Courses and texts on American Jewish food cultures have found a home in academia, such as Rachel Gross’ “Food Fights: The Politics of American Jewish Consumption, 1654-present,” which she teaches at San Francisco State University. In western North Carolina, Jennifer Lapidus, the Jewish owner-founder of Carolina Ground, is a leading figure in the southern grain revolution, where she is reconnecting independent farmers, millers, and bakers throughout the American South. At a 2020 Oneg Shabbat at Temple of Israel in Wilmington, North Carolina, Rabbi Emily Losben-Ostrov said the blessing over a first-time challah baked by one of her young women congregants.

Today Jewish women across the United States are sharing their expansive, personal expressions of American Jewish food on Instagram, in podcasts, blogs, on television and in film. From a farm on the North Dakota-Minnesota border, author and Food Network host Molly Yeh often explores the influence of her Jewish and Chinese roots in seasonal dishes that also reflect flavors of the upper Midwest. Contemporary expressions of keeping kosher in America are also seen in new cookbooks and digital sites such as Liz Rueven’s “Kosher Like Me,” where she emphasizes sourcing local, seasonal, and sustainable ingredients. Jake Cohen’s 2021 cookbook, Jew-ish, a modern take on American Jewish food, is evidence that a contemporary “nice Jewish boy” can now have a husband. Cohen’s frequent cooking demonstrations on TikTok, Instagram, television, and more during the months of Covid-19 quarantine reveal a new generation’s inclusive community and global reach. The Jewish Food Society, a women-led organization founded in 2017 by writer and culinary curator Naama Shefi, has a podcast “Schmaltzy” hosted by Amanda Dell, an e-newsletter, and an active Instagram feed dedicated to revitalizing and celebrating Jewish cuisine, its history, recipes, stories, and modern presentations.

For over four centuries, Jewish women in America have negotiated religiosity, citizenship, personal identity, economic livelihoods, consumerism, and the building of Jewish communities and families through their foodways in the United States—a deeply contested and beloved world of flavor, tradition, memory, and change. American Jewish women’s heads and hands in the kitchen, the synagogue, the marketplace, food venues, media, journalism, and now digital landscapes remain a strongly expressive force in how we experience and understand Jewish life in the United States.

Admony, Einot and Janna Gur. Shuk: From Market to Table, the Heart of Israeli Home Cooking. New York: Artisan, 2019.

Alpern, Liz, and Jeffrey Yoskowitz. The Gefilte Manifesto: New Recipes for Old World Jewish Foods. New York: Flatiron Books, 2016.

Amer, Robin. “The Last Jews of Natchez.” Southern Foodways Alliance Gravy Podcast, May 21, 2015. https://www.southernfoodways.org/gravy/the-last-jews-of-natchez-gravy-ep-14/

Ashkenazi, Elliot. The Civil War Diary of Clara Solomon: Growing Up in New Orleans, 1861-1862. Baron Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995, 334.

Braunstein, Susan L. and Jenna Weissman Joselit, eds. Getting Comfortable in New York: The American Jewish Home, 1880-1950. New York: The Jewish Museum, 1990.

Capelouto, Susannah. “Pie by Another Name: The Burekas of Or VeShalom.” Southern Foodways Alliance Gravy Podcast, August 24, 2017. https://www.southernfoodways.org/gravy/pie-by-another-name-the-burekas-of-or-ve-shalom/

Cohen, Jake. Jew-ish: Reinvented Recipes from a Modern Mensch. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021.

Deutsch, Jonathan and Rachel D. Saks. Jewish American Food Culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2008.

Diner, Hasia R. Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, & Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Diner, Hasia R. and Simone Cinotto, eds. Global Jewish Foodways: A History. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2018.

Diner, Hasia R. Roads Taken: The Great Jewish Migrations to the New World and the Peddlers Who Forged the Way. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Ferris, Marcie Cohen. Matzoh Ball Gumbo: Culinary Tales of the Jewish South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Graitcer, Philip. “Corned Beef Sandwiches in the Delta.” Southern Foodways Alliance Podcast, April 6, 2017. https://www.southernfoodways.org/gravy/corned-beef-sandwiches-in-the-delta/

Green, Edith. Oral interview with Joan Nathan, July 1991.

Gross, Aaron S., Jody Myers, and Jordan D. Rosenblum, eds. Feasting and Fasting: The History and Ethics of Jewish Food. New York: NYU Press, 2019.

Gross, Rachel B. “Jews, Schmaltz, and Crisco in the Age of Industrial Food.” In Feasting and Fasting: The History and Ethics of Jewish Food, eds. Aaron S. Gross, Jody Myers, and Jordan D. Rosenblum. New York: NYU Press, 2019.

Heinze, Andrew R. Adapting to Abundance. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Jacobs, Richard. Oral interview with Joan Nathan, 1991.

Joselit, Jenna Weissman. The Wonders of America: Reinventing Jewish Culture, 1880-1950. New York: Hill and Wang, 1994.

Joselit, Jenna Weissman, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Irving Howe, and Susan Braustein. Getting Comfortable in New York: The American Jewish Home, 1880-1950. New York: The Jewish Museum, 1990.

Kander, Lizzie Black. Microfilm material. American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati.

Katchor, Ben. The Dairy Restaurant. New York: Nextbook/Schocken, 2020.

Kempner, Aviva. “Yoo-Hoo, Mrs. Goldberg.” Documentary, 2009.

Koenig, Leah. Modern Jewish Cooking: Recipes & Customs for Today’s Kitchen. San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books LLC, 2015.

Koenig, Leah. The Jewish Cookbook. London: Phaidon Press Limited, 2019.

Krone, Adrienne. “Ecological Ethics in the Jewish Community Farming Movement.” In Feasting and Fasting: The History and Ethics of Jewish Food, eds. Aaron S. Gross, Jody Myers, and Jordan D. Rosenblum. New York: NYU Press, 2019.

Levy, David. "The orange on the seder plate and Miriam's Cup: Foregrounding women at your seder." 12 March 2012. Jewish Women's Archive. <https://jwa.org/blog/he-orange-on-seder-plate-and-miriams-cup-foregrounding-women-at-your-seder>.

Marcus, Jacob Rader. Memoirs of American Jews, 1775–1865. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1955.

Merwin, Ted. Pastrami on Rye: An Overstuffed History of the Jewish Deli. New York: NYU Press, 2015.

Lipman, Steve. “Crashing the Kosher Party.” The Jewish Week, October 29, 2004.

Nathan, Joan. The Foods of Israel Today. New York: Knopf, 2001.

Nathan, Joan. Jewish Cooking in America. New York: Knopf, 1994.

Nathan, Joan. The Jewish Holiday Kitchen New York: Schocken Books, 1979.

Nathan, Joan. “Lights of Life, Food of Memory.” The New York Times, December 1, 2004.

Nathan, Joan. “A Social History of Jewish Food in America.” In Food & Judaism, ed. Leonard J. Greenspoon, Ronald A. Simkins, and Gerald Shapiro. Omaha, NE: Creighton University Press, 2005.

Nathan, Joan. King Solomon’s Table: A Culinary Exploration of Jewish Cooking from Around the World. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017.

Newhouse, Alana, ed. The 100 Most Jewish Foods: A Highly Debatable List. New York: Artisan, 2019.

Orlovsky-Schnitzler, Justine. "The Politics of Holiday Preparation." 4 March 2021. Jewish Women's Archive <https://jwa.org/blog/politics-holiday-preparation>.

Ottolenghi, Yotam and Sami Tamimi. Ottolenghi: The Cookbook. New York: Ten Speed Press, 2013.

Rao, Tejal. New York Times, March 10, 2021.

Roden, Claudia. The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York. New York: Knopf, 1996.

Schleifer, Yigal. “Kashrut Goes Global.” The Jerusalem Report, December 13, 2004.

Sharfman, I. Harold. Jews on the Frontier. Malibu, CA: Joseph Simon Pangloss Press, 1977.

Shaya, Alon. An Odyssey of Food, My Journey Back to Israel. New York: Knopf, 2018.

Sussman, Adeena. Sababa: Fresh. Sunny Flavors from My Israeli Kitchen. New York: Avery, 2019.

Twitty, Michael. The Cooking Gene: A Journey Through African American Culinary History in the Old South. New York: HarperCollins, 2017.

Uhry, Alfred. Driving Miss Daisy. New York: Theater Communications Group, 1996.

Zeller, Benjamin E., Marie W. Dallam, Reid L. Neilson, Nora L. Rubel, eds. Religion, Food, & Eating in North America. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014.

Ziegelman, Jane. 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement. New York: Harper, 2010.