Women Warriors

In the Hebrew Bible and ancient Jewish literature, some women kill. Deborah, the only female judge of Israel, helps lead the Israelite army to war against the Canaanites. During that same war, a woman named Jael lures the Canaanite general into her tent, then kills him with a tent peg through the head. Later in the period of the judges, a man named Abimelech sets himself up as king and tries to take the town of Thebez. Abimelech is felled by a stone dropped from a tower by an unnamed women of Thebez. In the apocryphal Book of Judith, the eponymous heroine talks her way into the Assyrian camp and beheads the Assyrian general with his own sword.

In the Hebrew Bible, most warriors are men. Some female characters order killings or otherwise play a role in them but do not directly kill or go to war: Delilah (Judges 16), who persuades Samson to reveal his weakness to her, which leads to his capture and ultimate death; the wise woman of Abel Beth-Maacah (2 Samuel 20), who saves her town by making a deal with King David’s general Joab to have the head of the rebel Sheba cut off and sent out to Joab; and Esther, who accuses her enemy Haman, leading to his execution, and then successfully requests the execution of Haman’s ten sons (Esther 7-9).

This article, however, focuses on a handful of women who kill or go to war more directly: Jael, Deborah, the unnamed woman of Thebez, and Judith.

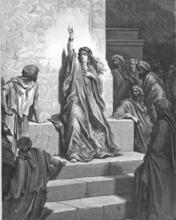

Deborah and Jael

Two of these women, Deborah and Jael, are present in the same story, Judges 4-5. We first meet Deborah in Judges 4:4, when she is introduced as a judge and prophet. The judges of the Bible are not by and large jurists, but rather a hybrid of military commander and governor. According to the Book of Judges, they govern Israel after the Israelites enter the Promised Land of Canaan but before they establish a monarchy. The book discusses many of the judges’ conquests, both successful and unsuccessful. Deborah is the only female judge, and also the only one described as adjudicating cases: “She would sit under the palm tree of Deborah between Ramah and Bethel in the hill country of Ephraim, and the Israelites would come up to her for judgment” (Judg 4:5). Although Deborah is not described as wielding a weapon, we should still interpret her as a warrior. Several male judges and generals are never described fighting, but we generally assume they did; we should make the same assumption about Deborah. Moreover, even if she does not engage in combat, she behaves like a general, ordering the commander Barak to attack the Canaanite general Sisera’s troops at Kadesh (Judg 4:6-7). Barak says he will only go to war if Deborah goes with him—and she does (Judg 4:9-10, Judg 5:15). Deborah does place a condition on her accompaniment of Barak: she tells him that, because he has asked her to go with him, “There will be zero glory for you on the path you will take, for the Lord will sell Sisera into the hand of a woman” (Judg 4:9). For a military commander to lose the most important kill of the battle to a woman is meant to be shameful.

The reader is supposed to believe that Deborah will take down Sisera, since she is the only woman we have encountered thus far—but this is not what happens. In Judges 4:17, we meet Jael, identified simply as the wife of Heber the Kenite. The text says that the Kenites are mostly allied with Israel, but Heber is allied with Canaan and has separated himself from the rest of the clan. Sisera, who has been routed at Kadesh, gets down from his chariot and flees on foot to Jael’s tent; presumably, the reader is meant to understand that he was hoping for shelter from his ally Heber. Instead, he meets Jael, who comes out of her tent and beckons Sisera: “Turn aside, my lord, turn aside to me! Do not be afraid” (Judg 4:18). Sisera comes into Jael’s tent and she gives him a drink of milk and tucks him under a rug or blanket. When he falls asleep, she comes to him softly and, using a hammer, drives a tent-peg through his head and kills him. She then goes out to meet Barak, who is pursuing Sisera, beckons him into her tent, and shows him the dead general (Judg 4:18-22). There are suggestions of both motherhood and seduction in this text. In Jael’s reassurances to Sisera, her care for him in the tent, and her feeding him milk, she acts like a mother. In Jael’s forthright “turn aside to me,” her presence alone in the tent with a man unrelated to her, and her forced penetration of Sisera with a tent peg, we can see sexuality.

After the prose telling of Deborah and Jael’s intertwined stories in Judges 4 comes a poetic version in Judges 5. In the poem, conventionally known as the Song of Deborah, Deborah praises herself (or is praised; the Hebrew is uncertain) as “a mother in Israel.” We can best understand this not as a statement that Deborah has given birth to and raised children, but rather as a metaphorical statement of her leadership of and care for the Israelites. The poem details the parties to the battle between Israel and Canaan before recounting Jael’s heroic deed. In this version, Jael feeds Sisera milk and curds, then kills him with the mallet and tent-peg. There is no suggestion that Sisera is sleeping when Jael strikes him; instead, the poem says, “Between her feet he bowed, he fell, he lay, Between her feet he bowed, he fell, Where he bowed, There he fell, destroyed” (Judg 5:27). Finally, the poetic version juxtaposes the scene of Sisera lying dead between Jael’s feet with a scene of his mother awaiting his return. Sisera’s mother, who is unnamed, wonders why he has not come back from battle and imagines that he and his men must be dividing the plunder: “A womb or two for each man’s head, Spoil of dyed cloth for Sisera, Spoil of dyed cloth, An embroidered cloth or two, Spoil for their necks” (Judg 5:30). The language of sex and motherhood is well used in this chapter.

The Unnamed Woman of Thebez

Judges 9 also includes a story of a woman warrior, although it is very brief and the woman is unnamed. In this chapter, a man named Abimelech murders his brothers and sets himself up as a king. He faces resistance from the town of Thebez, where all the residents move into a tower to escape Abimelech’s attack. Abimelech approaches the entrance to the tower to set it ablaze, but a woman at the top of the tower strikes first: “But one woman threw a millstone on Abimelech’s head and crushed his skull. He called hurriedly to the young man who carried his armor, ‘draw your sword and kill me, lest they say of me, a woman killed him,’ so his young man pierced him through and he died” (Judg 9:53-54). Abimelech’s death is framed as God’s punishment for Abimelech slaying his brothers. Abimelech does not want to be shamed posthumously for dying at a woman’s hand, so he commits suicide-by-proxy instead. In trying to assert his masculinity through battle prowess, he instead is emasculated. Evidently, his desire to escape shame for being killed by a woman is unsuccessful, because in 2 Samuel (generally thought to be written by the same author or authorial school as Judges, the Deuteronomistic Historian), Abimelech’s death is invoked as a cautionary tale for not getting too close to a city wall during battle (2 Sam 11:21).

Judith

Another woman warrior is found in a book written as a Jewish holy text but not adopted into the canon of the Tanakh. The Book of Judith was included in the Christian Old Testament and is still considered authoritative for Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christians today. In this text, the Assyrian army is conquering towns all over the Levant, but the Israelite town of Bethulia is resisting. The town’s male elders, seeing children dying of hunger and thirst, want to give God five days to rescue them and, failing divine action, to surrender to Assyria (Jdt 7). A wealthy, pious, and beautiful widow named Judith devises her own plan: she beautifies herself even further and, with her maidservant, walks out of Bethulia and into the Assyrian camp. Using her beauty and her wits, she convinces the Assyrian general, Holofernes, that she has defected and will help him conquer Israel (Jdt 10). Judith spends three days in the Assyrian camp, at which point Holofernes invites her to a drinking party where, it is understood, she will have sex with him. Holofernes, in his lustful excitement, drinks so much that he passes out, and Judith beheads him with his own sword. She and her maid leave the camp with Holofernes’ head in Judith’s food bag and reenter Bethulia (Jdt 12-13). Judith orders Holofernes’ head hung on the city wall, and, when the Assyrians wake to find their general’s headless body in his tent and his head posted on the gate of Bethulia, they scatter in terror. Israel is saved, and Judith leads a victory dance and song. She receives many marriage proposals but rejects them all, living out her life alone and dying at the ripe old age of 105 (Jdt 16).

Women Warriors Performing Femininity

The texts about women who kill men shame both the victims and the men who could not accomplish what a woman could. Deborah’s pronouncement that Sisera will be killed by a woman is a punishment for Barak’s cowardice in requesting that Deborah accompany him to war. When Deborah’s prophecy comes to pass and Sisera is slain by Jael, it is likely punishment for Sisera’s own cowardice in fleeing the battlefield. Sisera is infantilized through Jael’s acts of mothering—feeding him milk, reassuring him, and tucking him in—and, finally, lies destroyed at Jael’s feet. Abimelech is struck by the woman of Thebez as punishment for slaughtering his brothers and is so shamed that he tries to save face, even in death, by committing suicide by proxy. When Judith returns to Bethulia after killing Holofernes, she emphasizes that he was killed by “the hand of a woman” (Jdt 13:15). The people respond, “Blessed are you, our God, who has today humiliated the enemies of your people” (Jdt 13:16) The message is clear: Holofernes has been shamed through being outsmarted and killed by a woman.

Scholars have sometimes cast these stories as gender reversals, where the woman takes on male agency and the man is feminized to death. The logic is that, by taking up weapons of war, the women in these tales are acting like men. However, we can better see some of these characters as acting like women. Jael and Judith in particular perform aspects of womanhood—mothering and seduction—to get the generals right where they need them. The proximate murder weapons are a tent-peg and a sword, respectively, but the women would not have had the chance to use them were it not for their masterfully performed femininity.

Post-biblical interpretations of women warriors

One of the most extensive post-biblical treatments of Deborah and Jael is in the Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum, or the Biblical Antiquities. This book was transmitted to modern times alongside the work of Philo of Alexandria and was erroneously attributed to that famous Jewish philosopher and historian; the author is known today as Pseudo-Philo. In this retelling of the Bible, dated by most scholars to the first century of the Common Era, Pseudo-Philo enhances many of the stories of biblical women. In the case of Deborah, her role as a metaphorical “mother” is magnified. Before her death, she gathers the Israelites to speak to them as their mother, and, when she dies, they mourn her as a mother (L.A.B. 33). In Jael’s case, the Biblical Antiquities makes the character more seductive, even having her scatter rose petals on her bed to entice Sisera. Sisera falls for her instantly and swears to himself that if he survives the war, he will take Jael home to his mother and make her his woman. She is also more pious, praying to God for guidance when Sisera is in her tent (L.A.B. 31).

Rabbinic texts are generally positively disposed toward Deborah. The Rabbis classify her among the seven female prophets of Israel and extol her abilities as a judge (BT Meg. 13a:14). Interestingly, the Rabbis often envision Deborah and Barak as wife and husband. Deborah is said in Judges to be “wife of Lappidot” (alternatively, “woman of flames/torches”), so the Rabbis sometimes identify Barak as another name for the otherwise-unknown Lappidot. The Rabbis are trying to solve a puzzle in the text—who is Lappidot and why is he never mentioned again?—but perhaps also to inscribe the boundary-breaking Deborah in the traditional nuclear family. In one spot, the Rabbis speak negatively of Deborah: they report that, because she was haughty and proclaimed herself “a mother in Israel,” the gift of prophecy left her (BT Pes. 66b).

The Rabbis view Jael positively, describing her as a righteous convert to Judaism. Often, they play up the sexual and maternal aspects of Jael’s story. Some rabbinic texts try to preserve Jael’s honor by emphasizing that there was no sexual contact between her and Sisera in her tent (Lev. Rab. 23:10). Other texts suggest the opposite, with one midrash declaring that Jael had sexual intercourse with Sisera seven times to exhaust him before killing him (BT Yev. 103a). Another midrash has Jael feeding Sisera milk from her breast (BT Nid. 55b). The Rabbis do not see Jael as guilty of violating hospitality standards by taking Sisera in and then killing him, since she acted for the sake of the people of God.

The woman of Thebez appears only briefly and is not named, which may explain why she is mostly absent from postbiblical interpretation. She is mentioned in Josephus (Ant. 5:7), but his telling of the story does not add anything significant to Judges 9. In A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash, she is referred to briefly as “a hero…from above.” (Midrash Tanḥuma Buber Lev. 13:1)

Perhaps because Judith was eventually excluded from the Tanakh, there is much less post-biblical literature about her than about Jael and Deborah. Judith is entirely absent from the Dead Sea Scrolls, Philo, Josephus, Mishnah, Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Gemara, and other rabbinic works. Judith only becomes the subject of post-biblical speculation in the Middle Ages, when Jewish commentators begin to link her with the holiday of Lit. "dedication." The 8-day "Festival of Lights" celebrated beginning on the 25th day of the Hebrew month of Kislev to commemorate the victory of the Jews over the Seleucid army in 164 B.C.E., the re-purification of the Temple and the miraculous eight days the Temple candelabrum remained lit from one cruse of undefiled oil which would have been enough to keep it burning for only one day. Hanukkah. This may be because of parallels between Judith and Esther; both women save their people, and the latter has the holiday of Purim associated with her.

Ackerman, Susan. Warrior, Dancer, Seductress, Queen: Women in Judges and Biblical Israel. New York: Doubleday, 1998.

Carman, Jon-Michael. “Abimelech the Manly Man: Judges 9:1-57 and the Performance of Hegemonic Masculinity.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 43 (2019): 301-316.

Exum, J. Cheryl. “‘Mother in Israel’: A Familiar Figure Reconsidered.” In Feminist Interpretations of the Biblel, edited by Letty M. Russell, 73-85. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1985.

Gera, Deborah Levine. “The Jewish Textual Traditions.” In The Sword of Judith: Judith Studies across the Disciplines. Open Book Publishers, 2010. https://books.openedition.org/obp/986

Kadari, Tamar. “Deborah 2: Midrash and Aggadah.” The Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/deborah-2-midrash-and-aggadah

Kadari, Tamar. “Jael Wife of Heber the Kenite: Midrash and Aggadah.” The Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/jael-wife-of-heber-kenite-midrash-and-aggadah

Sasson, Jack M. Judges 1-12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. The Anchor Yale Bible. New Haven, Conn.: Yale, 2014.

Tamber-Rosenau, Caryn. “The ‘Mothers’ Who Were Not: Motherhood Imagery and Childless Women Warriors in Early Jewish Literature.” In Mothers in the Jewish Cultural Imagination, edited by Jane L. Kanarek, Marjorie Lehman, and Simon J. Bronner, 185-206. Jewish Cultural Studies 5. Oxford: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2017.

Tamber-Rosenau, Caryn. Women in Drag: Gender and Performance in the Hebrew Bible and Early Jewish Literature. Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias, 2018.