Two Prostitutes as Mothers: Midrash and Aggadah

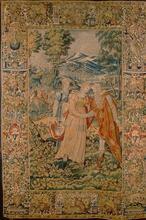

The two prostitutes appear in the narrative about Solomon’s judgement concerning the parentage of a baby boy. The judgement itself is considered to be unequivocally correct, but the Rabbis debate the identity of the women. Some argue that the women truly were prostitutes and were therefore not present at the time of the judgment, while others assert that they were yevamot (widows whose husbands had died childless). Another opinions views them as spirits and sees the episode as intended to demonstrate Solomon’s wisdom.

Identities

The Rabbis disagree regarding the identity of the two “prostitutes” mentioned in I Kings 3. One hermeneutical view (Cant. Rabbah 1:1:10) maintains that they were The widow of a childless man whose brother (yavam or levir) is obligated to marry her to perpetuate the brother's name (Deut. 25:5yevamot (widows whose husbands had died childless), based on the assumption that harlots usually do not want the children born as a result of their profession and therefore abandon them. These women, however, were yevamot and therefore each wanted the child in order to be freed of the obligation of yibbum (Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).levirate marriage).

According to another opinion, they were spirits and not human beings (Cant. Rabbah loc. cit.). This view emphasizes the Heavenly direction of the episode, which was intended to demonstrate Solomon’s wisdom and firmly establish his standing with the people. Solomon ascended the throne while still a youth, as he attests of himself (v. 7): “but I am a young lad, with no experience in leadership.” The judgment of the prostitutes demonstrated to all that, despite his tender age, he was capable of judging the people wisely. The demonstrative goal of the judgment was achieved, as is seen in v. 28: “When all Israel heard the decision that the king had rendered, they stood in awe of the king, for they saw that he possessed divine wisdom to execute justice.”

Other Rabbis, however, argue that the women were actual prostitutes and Solomon delivered their judgment without witnesses (Cant. Rabbah loc. cit.). God thus fulfilled the request of David, who had prayed to God (Ps. 72:1): “O God, endow the king with Your judgments, the king’s son with Your righteousness.” David said: “Master of the Universe, ‘endow the king’s son with Your judgments’—just as You judge without witnesses, so, too, let Solomon judge without witnesses.” God responded: “Let it be so.” I Chron. 29:23 accordingly attests: “Solomon successfully took over the throne of the Lord”—but can flesh and blood sit on the throne of the Lord? Rather, Solomon judged like his Maker, without witnesses, in the judgment of the prostitutes (A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash Tehilim 72:2).

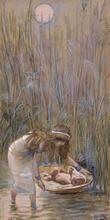

The Judgment

The Rabbis learned from the judgment of Solomon how a trial is to be conducted. The judge sits and the defendants stand, with the plaintiff between them. The plaintiff raises the charges, the defendant responds and the judge decides between them (Eccl. Rabbah 10:16:1). The Rabbis further deduced that the judge must repeat the claims of the plaintiff to the defendant, and those of the defendant to the plaintiff, just as Solomon did (v. 23): “The king said, ‘One says, “This is my son, the live one, and the dead one is yours,” and the other says, “No, the dead boy is yours, mine is the live one”’” (Deut. Rabbah 5:6).

The midrash relates that when Solomon threatened to cut the infant into two, wisdom began issuing forth from his mouth. He said: “God anticipated that this judgment would come before me. He therefore created man with two eyes, two ears, two nostrils, two hands and two feet [so that cutting the child into two would produce two completely identical halves].” When Solomon ordered (v. 24): “Fetch me a sword,” those in attendance at the court thought that Solomon’s youth was evident in the manner in which he delivered his judgment. If the child’s real mother had not immediately been overcome by her compassion for her son, he would already be dead.

Those present thought that the king should have put a cord around the child’s neck and threatened to strangle him, for this is a death that is not immediate and allows for second thoughts. The members of the court applied to that moment Eccl. 10:16: “Alas for you, O land whose king is a boy.” However, once Solomon ruled (v. 27): “Give the live child to her, and do not put it to death,” they were cognizant of Solomon’s wisdom and applied to him the verse (Eccl. 10:17): “Happy are you, O land whose king is a master” (Eccl. Rabbah 10:16:1; Midrash Tehilim 72:2).

Analyses of the Judgment

The Rabbis include the judgment of Solomon among the three instances in which God appeared in a court and spoke: in the court of Shem, in the court of Samuel and in the court of Solomon, in the trial of the prostitutes (Midrash Tehilim loc. cit.). Solomon determined who the real mother was and ruled: “Give the live child to her, and do not put it to death,” at which point a Heavenly voice went forth, saying (at the end of that verse): “she is its mother” (BT Makkot 23b).

According to this midrashic account, if the Heavenly voice had not gone forth, the problematic nature of this ruling would have remained, since it could always be argued that the woman deceived Solomon and merely pretended to have mercy on the infant so that she would be thought to be the child’s real mother. But the Heavenly voice that intervened unequivocally established the correctness of Solomon’s ruling and that his judgment was just.