Rachel: Midrash and Aggadah

While Rachel was barren for the first fourteen years of her marriage, she is still described as Jacob’s preferred wife and a powerful woman. Jacob’s other wife is Rachel’s sister Leah, which causes issues between the sisters, especially because Leah is able to bear children. Rachel initially relies on her handmaiden Bilhah to bear children in her place, but Rachel eventually becomes pregnant and goes on to have one other child. However, the Rabbis debate the reason behind God granting her the ability to bear children. Overall, the midrash portrays Rachel as incredibly generous and compassionate, and her goodness is seen in her descendants.

Introduction

Rachel is depicted in the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah as Jacob’s beautiful and beloved wife. His preference for her continued even after her death, and also influenced Jacob’s attitude to her children. The Rabbis speak of the passionate love for Rachel exhibited by Jacob, who already understood from their first encounter that she was his intended bride.

At the same time, they also illustrate the intricate and complex relationship between Leah and Rachel, the two sisters and the two wives of Jacob whose fate was intertwined. The Rabbis teach of Rachel’s compassion for her sister, that prevailed over her loyalty to Jacob, along with the unending tension between the two women who lived under the same roof. Rachel’s barrenness intensified the jealousy between them, but Leah, out of demonstrated compassion for her sister, prayed that she give birth. The contention between the two women did not cease even after Rachel’s death, and arose again as regards the seniority of Jacob’s sons: who would be considered the firstborn—the son of Leah, or of Rachel; and similarly, regarding the origin of Elijah, the harbinger of the Redemption.

The Rabbis are lavish in their praise of Rachel, whom they describe as merciful, and who waived her personal benefit and desires on behalf of her sister. An additional important trait of Rachel’s was the art of silence and the ability to keep secrets, a quality that she also passed on to her offspring, who were known for their taciturnity: Benjamin, Saul, and Esther.

Rachel’s good deeds also positively influenced her children. By her merit, Joseph was given the birthright, and her descendants rose to royalty, leadership, and greatness. The A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash portrays Rachel as a prophetess, and her statements and the names she gave her sons contain allusions to the future. Rachel’s merit continued to aid Israel even many years after her demise: when the exiles from Judah (after the destruction of the First Temple) passed by her tomb, she aroused God’s mercy to forgive them; He heeded her, and promised her that He would return them to their land.

Rachel’s Beauty

Gen. 29:17 attests: “Leah had weak eyes; Rachel was shapely and beautiful.” The midrash adds that there was no maiden fairer than Rachel (Tanhuma, Vayeze 6). Another tradition explains the Torah’s statement (Gen. 29:16): “Now Laban had two daughters” as meaning that both were equal in beauty and in their erect stature (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 12). According to another tradition, Rachel and Leah were twins, and they were married to Jacob at the age of twenty-two (Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder Olam Rabbah 2).

The Encounter by the Well

Gen. 29 tells of the first meeting between Jacob and Rachel at the well. When Jacob saw Rachel coming with the flock, he rolled the heavy stone from the mouth of the well by himself, a task that normally required more than three men; in the midrashic exposition, he rolled the stone as someone who removes a stopper from a flask (Gen. Rabbah 70:12). This exposition aims to applaud Jacob’s strength, which increased due to his love for Rachel.

Gen. 29:10–11 tells how Jacob watered Rachel’s flock, and then kissed her and wept. The Rabbis were concerned with the nature of this kiss, which they regarded as an improper act. They assert that Jacob’s kiss was not a wanton one, but one that expressed familial feeling, since Rachel was related to him (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). The midrash lists three reasons for Jacob’s crying on this occasion. The first was his anguish at his poverty. Jacob said to himself: “When Eliezer, the servant of Abraham, went to fetch Rebekah, he brought with him ten camels and all the bounty of his master (Gen. 24:10), while I have not a single nose-ring or band.” The second reason for his weeping was his foreseeing that Rachel would not be buried together with him (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

These two reasons reveal the fact that, already at the instant of his first meeting with Rachel, Jacob realized that she was the woman meant for him. He knew that he would marry her, just as Rebekah had been married to Isaac, and he also understood that he would bury her. According to a third tradition, Jacob wept for grief, for he realized that after he kissed Rachel people were whispering to one another: “Why has this one come, to teach us this indecent behavior?” The midrash comments that after the world had been struck by the Flood, the nations of the world hedged themselves against illicit sexual behavior [i.e., they accepted all manner of sexual prohibitions] (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

When Jacob introduced himself to Rachel, he told her (v. 12) “that he was her father’s kinsman, that he was Rebekah’s son.” In the midrashic expansion, Jacob told Rachel: if to deceive—he was her father’s kinsman; and if for righteousness—he was Rebekah’s son. When Rachel heard this, she ran to tell her father. The Rabbis observe that a woman usually goes to her mother’s household, but since Rachel’s mother was dead, she had none to tell about Jacob besides her father (Gen. Rabbah 70:13).

Rachel the Beloved Wife

Gen. 29:18 attests: “Jacob loved Rachel.” The midrashic exegesis of this verse characterizes this love of Jacob’s with a reference to Cant. 8:6: “For love is fierce as death” (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeshev 19). In another midrashic tradition, however, Jacob did not initially favor Rachel over Leah. He asked for Rachel’s hand because he thought that Leah was intended for Esau (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 12).

“When Morning Came, There Was Leah!”

The Rabbis present Laban’s act of deceit as something in which Rachel was involved, from which they learn of her special qualities. The midrash relates that there was no maiden comelier than Rachel, which was why Jacob desired to wed her, and sent her presents. Laban would take these gifts and give them to Leah, and Rachel would remain silent (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 6). Jacob asked Rachel: “Will you marry me?” She answered: “Yes, but my father is a deceiver, and you will not be able to best him.” He asked her: “What is his deceit [in what will he be able to deceive me]?” She told him: “I have an older sister, and he will not marry me off before her.” He said: “I am his brother in deceit.” Jacob gave Rachel signs [so that he would be able to recognize her on their wedding night].

When Leah was brought under the wedding canopy, Rachel thought: “Now my sister will be shamed [when Jacob discovers the fraud and does not marry her].” She gave the signs to Leah. This is why Gen. 29:25 relates: “When morning came, there was Leah!”—because Rachel had given her the signs, Jacob did not know until the morning that they had switched (BT Bava Batra 123a).

According to the Rabbis, Laban would not have succeeded in deceiving Jacob without Rachel’s involvement. Rachel had to choose between her love for Jacob and her compassion for her sister, and she decided in favor of the latter. The most extreme description of Rachel’s act of self-sacrifice appears in Lam. Rabbah, according to which Rachel entered under Jacob and Leah’s bed on their wedding night. When Jacob spoke with Leah, Rachel would answer him, so that he would not identify Leah’s voice (Lam. Rabbah [ed. Vilna] petihtah 24).

After he married Leah, Jacob held a banquet for seven days, and he added another seven days of feasting and rejoicing, and then married Rachel. The Rabbis learned from this that seven days of feasting are to be conducted for a bride and groom (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer [ed. Higger], chap. 16).

“But Rachel Was Barren”

The midrash relates that Rachel was twenty-two years old when she was married to Jacob (Seder Olam Rabbah 2), and her barrenness lasted for fourteen years (Seder Eliyahu Rabbah 18, p. 99).

The Rabbis understand the wording (Gen. 29:31): “but Rachel was barren [akarah]” as teaching of Rachel’s merit: despite her not having children, she nonetheless was the chief person [ikar] of the household. Another tradition explains that most of those around [the table] were from Leah, and therefore Rachel was the main person [ikar] of the household (Gen. Rabbah 71:2). Leah was busy with raising her children and therefore could not care for the needs of the household. Rachel, who was not so occupied, therefore became the mainstay of the household. These two exegetical positions derive the word “akarah” from “ikar.” The first view maintains that even though Leah had children, Rachel continued to be the beloved and preferred wife, which was expressed in the running of the household. According to the second opinion, however, the fact that she was the chief person of the household was a result of her barrenness and did not necessarily reflect Jacob’s preference for her.

Yet another tradition asserts that this was not stated to Rachel’s credit, and confirms the fact of her barrenness. As compensation for this negative depiction, Scripture calls Israel after her, after her son, and after her son’s son. In Jer. 31:15 Israel is called after Rachel: “Rachel weeping for her children”; in Amos 5:15 Israel is named after her son: “Perhaps the Lord, the God of Hosts, will be gracious to the remnant of Joseph”; and in Jer. 31:20 Israel is called after her son’s son: “Truly, Ephraim is a dear son to Me” (Ruth Rabbah 7:11:13). This midrash indicates a certain correction of the injustice done to Rachel. Since she suffered many years of barrenness, she was rewarded by the Israelites being called by her name, or by the name of her descendants. In this manner, the barren women became one of the Matriarchs of the nation.

Rachel Is Jealous of Her Sister

Gen. 30:1 states: “When Rachel saw that she had borne Jacob no children, she became envious of her sister,” leading the Rabbis to apply to Rachel the verse Cant. 8:6: “Passion [kinah, literally, jealousy] is mighty as Sheol”—this was Rachel’s jealousy of her sister (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeshev 19). In another tradition, Rachel envied Leah’s good deeds. Rachel said: “If Leah were not righteous, would she have given birth?” (Gen. Rabbah 71:6). In this midrash, Rachel has the insight that the birth of children is a reward from God. Rachel feared that her deeds were not favorable in the eyes of God, which resulted in her barrenness.

Gen. 30:1 relates that when Rachel saw that she was not bearing children, she told Jacob: “Give me children, or I shall die,” leading the Rabbis to conclude that whoever is childless is regarded as dead (Lam. Rabbah 3:2). Jacob’s response is described in v. 2: “Jacob was incensed at Rachel, and said, ‘Can I take the place of God, who has denied you fruit of the womb?’” The midrashic exegesis further intensifies Jacob’s strong statement. Jacob said to Rachel: “who has denied you fruit of the womb”—He denied “you,” but me He did not deny [since I have sons from Leah]. God said to Jacob: Is this how one replies to embittered women? By your life, your sons will stand before her son, and he will tell them (Gen. 50:19) “Am I a substitute for God?” (Gen. Rabbah 71:7).

This midrash criticizes Jacob for responding so harshly and inconsiderately to Rachel, who is presented as a bitter woman. Jacob should have understood her pain, instead of rebuking her for the manner in which she spoke. Instead of showing understanding, he amplifies her pain by telling her that he already has four sons from Leah. As punishment for Jacob’s behavior, Leah’s sons will stand before Joseph, the ruler of all Egypt, hear the same words coming out of his mouth and fear him, not knowing how he will act toward them [after Jacob’s death].

Rachel asks Jacob: “Is this how your father [Isaac] acted toward your mother [Rebekah]? Did he not gird his loins for her [since Isaac strove and prayed so that Rebekah would become pregnant]?” Jacob replied: “He did not have children, I have children [I already have four sons from Leah].” Rachel retorted: “And did not your grandfather [Abraham] have children [Abraham had Ishmael], yet he girded his loins for Sarah [nonetheless, he made the effort of praying so that Sarah would become pregnant]?” He told her: “You can do as my grandmother [Sarah] did.” She asked him: “And what did she do?” He replied: “She brought a rival wife [Hagar] into her house.” She responded: “If this is the obstacle, [then] (Gen. 30:3): “‘Here is my maid Bilhah. Consort with her […] that through her I too may have children’” (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). This midrash compares the barrenness of the three Matriarchs and the conduct of the three Patriarchs, which intensifies the criticism of Jacob, who should have acted as his forefathers did, and pray on behalf of Rachel in accordance with her wishes.

Bilhah, Rachel’s Maid

Rachel had been given Bilhah as a handmaiden by her father Laban upon her marriage to Jacob. When Rachel saw that she did not bear children, she followed in the footsteps of Sarah: just as she [Sarah] had been “built” (i.e., had children) through her rival wife [Hagar], so too, this one [Rachel] would be built by her rival wife [Bilhah] (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). The midrash further relates that Jacob loved Rachel more than Leah, and he even loved Bilhah, Rachel’s handmaiden, more than he loved Zilpah, the handmaiden of Leah (Gen. Rabbati, Vayeze, p. 120).

The Children of Bilhah

Bilhah bore Jacob two sons, Dan and Naphtali, the first by her own merit, and the second by the merit of Rachel (Gen. Rabbati, Vayeze, p. 121). The Torah states that Rachel named Bilhah’s sons.

When Dan was born, Rachel said (Gen. 30:6): “God has vindicated me [dananni]; indeed, He has heeded my plea and given me a son.” In the midrashic explication of this verse, Rachel said: “God has judged me and found me guilty [and therefore I was childless]”; [and afterwards] “He has judged me and vindicated me [and given my handmaiden a son]” (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

At Naphtali’s birth, Rachel said (Gen. 30:8): “A contest of God, a fateful contest I waged [naftulei … niftalti] with my sister; yes, and I have prevailed.” The midrash gives four different interpretations of this name. According to the first, Naphtali’s name is an acrostic of all that happened between Rachel and her sister. Rachel said: “I prepared myself [nupeti, i.e., I prepared myself for Jacob’s bed], I allowed myself to be persuaded [pititi—to withdraw in favor of my sister and to aid her to be Jacob’s wife], I exalted my sister over myself [taliti ahoti alai], ‘and I have prevailed’” (Gen. Rabbah 71:8). When Naphtali was born, Rachel felt that her competition with her sister had reached a point of equilibrium. She had started from a position of superiority over her sister, since she was the desired wife. Then she waived this status when she consented to Leah’s marriage to Jacob. Consequently, Rachel found herself in an inferior position, since Leah bore children to Jacob, while she herself had not. Only now, upon the birth of Naphtali, did Rachel sense that she had regained her former standing.

According to another tradition, the word “naftali” is to be derived from ninfei (bride). Rachel said: “I should have been Jacob’s bride before my sister. If I had sent a message to him, saying: ‘Take note that they are deceiving you,’ would he not have refrained? Rather, I said: ‘If I am not worthy that the world should be built from me, let it be built from my sister’” (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.). Rachel knows that she is Jacob’s true intended bride. She performed the exchange fully aware of what she was doing, even though she knew that Leah would bear most of Jacob’s sons.

According to these first two traditions, Naphtali’s name portrays an experience undergone by Rachel. A third interpretation takes the word naftali from “pitulim [vicissitudes],” and describes what Jacob underwent. Rachel said: “Were not the vicissitudes that Jacob underwent for me? Did he not go to Laban only because of me?” (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.) In the fourth interpretive possibility, the name given by Rachel portrays the child’s character, thus predicting the future. Rachel said: “Naftali—he is my nofet [honeycomb].” Nofet are the words of Torah, that are called (Ps. 19:11) “drippings of the comb [nofet zufim],” which are in the portion of Naphtali, who will engage in Torah study (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.)

The Mandrakes

Gen. 30:14 relates that Reuben found mandrakes, which are prophylactic, in the field, and brought them to his mother Leah. When Rachel saw them, she asked Leah to give them to her [because of her barrenness]. In return, Leah requested that Rachel forgo her right to be with Jacob that night. The Rabbis did not view this exchange between the sisters favorably. Some criticized Leah, for by her actions she exhibited ingratitude to Rachel. God asked Leah: “Is this the reward for a good deed? Is this the reward of your sister Rachel, who gave you her signs with her husband on your wedding night, to spare you embarrassment?” As punishment for this behavior, Leah was caused even greater mortification with the episode of Dinah (Gen. Rabbati, Vayishlah, p. 168).

Other Rabbis found fault with Rachel and maintained that because Rachel made light of her right to lie with the righteous Jacob, which she sold for the mandrakes, she was punished by not being buried together with him. The exegetes holding this view find Rachel’s words (Gen. 30:15) to be somewhat prophetic: “I promise, he shall lie with you tonight”—“with you” he will lie [in the grave], but with me he will not lie [in the grave].

The Rabbis commented on the sale of the mandrakes: “This one lost and the other one lost, this one was rewarded and the other one was rewarded.” Leah lost the mandrakes and was rewarded with tribes; Rachel lost burial, and was rewarded with the birthright (Gen. Rabbah 72:3). This midrash incorporates several aggadic traditions according to which Leah gave birth to Issachar and Zebulun by merit of the mandrakes that she gave her sister. Rachel lost being buried next to Jacob because of her dealing with Leah, but she thereby merited having her son Joseph receive the birthright.

“Now God Remembered Rachel”

Leah bore Jacob six sons and a daughter. The midrash states that Leah carried a male fetus in her womb during her seventh pregnancy. When Rachel saw that her sister was pregnant, she prayed and caused the fetus’s sex to change (JT Berakhot 9:3, 14[a]). Another tradition has Leah herself being responsible for the change. Leah knew that twelve tribes would issue from Jacob. When she realized that she was pregnant and that Jacob already had ten sons (six from Leah, two from Bilhah, and two from Zilpah), she said: “Will my sister Rachel not be even as one of the handmaidens?” Leah prayed to God on behalf of her sister. God accepted her prayer and the sex of the fetus in her womb changed to female (BT Berakhot 60a; Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 19). According to another tradition, all three mothers (Leah, Bilhah, and Zilpah) gathered and said: “We have enough males; let her [Rachel] be remembered” (Gen. Rabbah 72:6).

Gen. 30:22 reveals: “Now God remembered Rachel; God heeded her and opened her womb.” In the midrashic expansion, Rachel was remembered (i.e., became pregnant) on The Jewish New Year, held on the first and second days of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. Referred to alternatively as the "Day of Judgement" and the "Day of Blowing" (of the shofar).Rosh Ha-Shanah, like Sarah and Hannah. On this date Joseph left the Egyptian prison; and on this date, Israel went forth from their servitude in Egypt (BT Rosh Hashanah 10b–11a). This midrash uses a common date to connect various historical events. The impregnation of Sarah and Rachel, the Matriarchs of the nation, heralds that God will also deliver their descendants from the troubles they would suffer in the future. Rosh Hashanah is perceived as the time of liberation from pain and sorrow: this is the day that signals a positive change, both in the time of the Matriarchs and in the time of their offspring.

The midrash relates that three keys remain with God and were not entrusted to an agent [=angel]: the key of rain, the key of the woman giving birth and the key of the resurrection of the dead. The Rabbis learn of God’s retaining the key of the woman giving birth from Rachel, of whom it is said: “Now God remembered Rachel; God heeded her and opened her womb” (BT Taanit 2a–b).

The Rabbis seek to discover the reason why Rachel’s womb was opened. One tradition maintains that she became pregnant by merit of abundant prayers: by merit of her own prayer, by merit of her sister’s prayer, by merit of Jacob’s prayer, and by merit of the prayer of the handmaidens [Zilpah and Bilhah] (Gen. Rabbah 73:3). In another tradition, God remembered Rachel’s silence when Leah was given to Jacob instead of her. Yet a third tradition explains that Rachel merited pregnancy because she brought her rival wife [Bilhah] into her house. By merit of the birth of Dan [the son of Bilhah], Rachel became pregnant; and by merit of the birth of Dan, Joseph and Benjamin were born (Gen. Rabbah 73:4).

The midrash includes Rachel among the seven barren women who were eventually blessed with offspring: Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, Leah, Manoah’s Wife, Hannah and Zion [in a metaphorical sense], of whom Ps. 113:9 states: “He sets the childless woman among her household as a happy mother of children” (Pesikta de-Rav Kahana [ed. Mandelbaum], Roni Akarah 20:1).

The Birth of Joseph

Gen. 30:23 records that when Rachel gave birth to Joseph she explained: “God has taken away [asaf] my disgrace.” The Rabbis observe that until a woman gives birth, whatever blame [there is, within the house] is placed upon her. If she breaks a vessel within the house, whom shall she blame for this? Once she has given birth, she places the blame on her child (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 19).

Some midrashim view the name given by Rachel to her son Joseph as a prophecy for what would befall his descendants. According to one of these interpretations, the “disgrace” to which Rachel refers is the affair of the Concubine of a Levite (Jud. 19–21) that occurred within the tribe of Benjamin; after the ban against this tribe had been lifted, that disgrace was expunged. In another midrashic understanding, Rachel alluded to the disgrace during the time of Jeroboam son of Nebat, who was a descendant of the tribe of Ephraim, and who engaged in idolatry and denigrated the prophet Ahijah of Shiloh (I Kings 12–14); this disgrace was taken away when Jeroboam was put to death (II Chron. 13).

Another tradition suggests that when Rachel saw that she did not bear children, she feared lest Esau take her from Jacob and marry her [because of the prior agreement between the parents of Jacob and Esau that each would marry one of the sisters, while Jacob had married both]. After Joseph’s birth, she exclaimed: “God has taken away my disgrace” (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 20).

When Joseph was born, Rachel stated (Gen. 30:24): “May the Lord add [yosef] another son for me.” The Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud asserts that the Matriarch Rachel was one of the first women prophets. She spoke in precise language when she said: “May the Lord add another son for me”—she did not say “other sons,” rather, there will be one more son from me. And, indeed, she bore Jacob only a single additional son, Benjamin (JT Berakhot 9:3, 14[a–b]). In yet another exegetical understanding, Rachel said: “May the Lord add another son for me” for exile, because the ten tribes were exiled beyond the Sambatyon river, while the tribes of Judah and Benjamin were dispersed throughout all the lands. In an additional commentary, “another son” referred to the apportioning of The Land of IsraelErez Israel, since Benjamin did not have a portion with Joseph, but with the tribe of Judah (Gen. Rabbah 73:5–6).

The Theft of the Household Idols

In the narrative in Gen. 31:19, when Jacob fled from Laban’s house, Rachel stole her father’s household idols. The Rabbis claim that Rachel did so for the sake of Heaven. She said: “We are leaving—shall we leave this old man in his corruption [i.e., idolatry]?” Consequently, Scripture proclaims her praise and tells of the act of theft (Gen. Rabbah 74:5). In another tradition, Rachel stole these idols so that they would not reveal to Laban that Jacob had fled with his wives, his children and his flocks (Tanhuma, Vayeze 12).

When Laban overtook Jacob in the hill country of Gilead, he reproached him (Gen. 31:30): “but why did you steal my idols?”, to which Jacob replied (v. 32): “But anyone with whom you find your gods shall not remain alive!” The midrash explains that this statement by Jacob was as an error committed by a ruler [which is nevertheless implemented—following Eccl. 10:5], and therefore Rachel died during childbirth (Gen. 35:19). Jacob allowed Laban to search for the idols. The midrash adds that Laban entered Rachel’s tent twice, because he knew that she was inclined to steal. Rachel had taken the idols and placed them in the cushion on her camel’s back. A miracle was performed for her, the idols were transformed into cups, and therefore Laban did not find them (Gen. Rabbah 74:9). These midrashic expositions cast Rachel’s act in a positive light. She did not want to adhere to the paganism of her father’s house, but rather sought to prevent Laban from engaging in idolatry. This exegetical direction is supported by the divine aid she received in the miraculous concealment of the idols from Laban.

In the midrashic account, many years later, when Joseph’s goblet was found in the sack of Benjamin (Gen. 44), the tribes stood about, beat Benjamin’s shoulders, and cried out: “Oh thief, the son of a thief, you have shamed us! You are your mother’s son! So did your mother shame our father when she stole the household idols from Laban!” By merit of the blows that he received on his shoulders, the Shekhinah (Divine Presence) would rest between Benjamin’s shoulders, as it is said in the blessing by Moses (Deut. 33:12): “Of Benjamin he said: Beloved of the Lord, he rests securely beside Him […] as he rests between His shoulders” (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Mikez 13). The Torah relates that it was Joseph who ordered that the goblet be hidden in Benjamin’s sack. Due to the shame that Benjamin suffered through no fault of his own, he merited having the Divine Presence rest in his portion [the Temple was erected in the portion of the tribe of Benjamin], which thereby publicly proclaimed his innocence. The purpose of the comparison between Benjamin and his mother was to say that just as Benjamin was unjustly accused, so, too, Rachel should not have been called a thief, since her motive was positive.

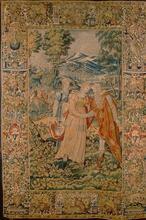

The Encounter between Jacob and Esau

Gen. 30:25 relates that after Joseph’s birth Jacob asked Laban for permission to return to his land. The midrash links the birth of Joseph and the departure from the house of Laban with the encounter with Esau. It speaks of a tradition possessed by Jacob that Esau would fall only by the hand of Rachel’s sons. Accordingly, after the birth of Joseph, Esau’s foil, Jacob resolved that the time had come to return to his homeland (Gen. Rabbah 73:7).

As related in Gen. 32:7, before the meeting with Esau, Jacob was apprehensive that his brother was preparing to fight him, and he therefore divided his family into two camps. Gen. 33:2 relates: “putting the maids and their children first, Leah and her children next, and Rachel and Joseph last,” to which the midrash comments: “The more behind, the more beloved” (Gen. Rabbah 78:8). Rachel and Joseph were most beloved by Jacob, and therefore they stood last. In another exegetical tradition, Jacob placed Rachel and Joseph last because he wanted to protect them. Jacob said: If all my children will be killed, Rachel’s son will remain, for he will punish this wicked seed, as it is said (Jud. 5:14): “From Ephraim came they whose roots are in Amalek” [literally: From Ephraim came those who will destroy Amalek from it’s roots]—and Israel will be rescued only by the son of Rachel. At that time God was revealed to Jacob and He told him: “Rachel’s children are with you, and you are afraid? Your life, they will exact punishment from him whenever he threatens your children” (Pesikta Rabbati [ed. Friedmann (Ish-Shalom)], chap. 13). The midrash views this confrontation between Jacob and Esau as symbolizing the future rivalries between the descendants of the two. Thus, for example, the Bejaminite Saul would wage war against and triumph against Amalek, the descendant of Esau; and Mordecai, from the tribe of Benjamin, would use his wisdom to best the Amalekite Haman. This midrash bore a message of consolation to the Rabbis and the Jews of their time, since, for the Rabbis, Esau symbolized the Roman empire. This exegesis hints that in the rivalry between Israel and Esau [= Rome] Rachel’s children would emerge victorious.

Gen. 33:6–7 describes the meeting with Esau: “Then the maids, with their children, came forward and bowed low; next Leah, with her children, came forward and bowed low; and lastly, Joseph and Rachel came forward and bowed low.” The Rabbis noted that the other wives came first and their children after them, while Joseph stepped forward before his mother Rachel. The reason for this was Joseph’s fear that Esau would see Rachel and desire her. He therefore went before her, stood up to his full height and hid her from Esau. Before his death, Jacob praises Joseph for acting in this manner, when he says of his son (Gen. 49:22): “Joseph is a wild ass, a wild ass by a spring [ayin, also meaning “eye”]”—I must reward you for that eye [for having concealed Rachel from Esau’s eye] (Gen. Rabbah 78:10).

The Birth of Benjamin and the Death of Rachel

In the tableau in Gen. 35:17, Rachel experiences difficulty in childbirth and the midwife tells her: “Have no fear, for it is another boy for you.” The Rabbis observe that this is how a woman’s spirit is restored during childbirth, by telling her not to fear, because she is giving birth to a son [which was regarded as an honor which would raise the woman’s spirits] (Gen. Rabbah 82:8).

Before her death, Rachel names the newborn. Gen. 35:18 attests: “But as she breathed her last—for she was dying—she named him Ben-oni; but his father called him Benjamin.” The Rabbis explain that Rachel called the child “the son of my suffering” [in Aramaic], while his father gave him the Hebrew name “Benjamin.” The midrashic sources specify that Rachel died at the age of thirty-six (Seder Olam Rabbah 2) and list three women who had difficult childbirths and died: Rachel, the wife of Phinehas (I Sam. 4:19), and Michal (daughter of Saul) (II Sam. 6:23) (Gen. Rabbah 82:7).

Why did Rachel die? According to one opinion, her death was a punishment for Jacob, for having made a vow and then not honoring it. When Jacob left the land of Canaan, he had vowed that he would return to Bethel and sacrifice to the Lord (Gen. 28:20–22). However, since he was delayed in fulfilling his vow [as is related in Gen. 35:1–7], he was punished by having to bury Rachel. The Rabbis learned from this that whoever makes a vow and delays fulfilling it will bury his wife (Lev. Rabbah 37:1). According to another tradition, Rachel died before Leah because she spoke before her sister. When Jacob wanted to leave Haran, he summoned his wives to the field and told them of his plans. They consented, as is said in Gen. 31:14: “Then Rachel and Leah answered, saying […].” Since Rachel spoke before her sister, she was punished by dying before her (Gen. Rabbah 74:4). An opposing exegetical view, however, notes that when Jacob sent for his wives to come to the field (Gen. 31:5), the Torah states: “Jacob had Rachel and Leah called to the field”—he called to Rachel first, and therefore she acted properly when she was the first to respond to him. Why, then, did she die? Because of the curse which Jacob uttered to Laban (Gen. 31:32): “But anyone with whom you find your gods shall not remain alive!” (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

When, toward the end of his life, Jacob told Joseph about Rachel’s death, he said (Gen. 48:7): “I [do this because], when I was returning from Paddan, Rachel died, to my sorrow.” The wording “died, to my sorrow” teach the Rabbis that Rachel’s death was the harshest of all the troubles that befell Jacob (Gen. Rabbah 97:7, [ed. Theodor-Albeck, MS. Vatican, p. 1243]). The Rabbis further learned from Jacob’s words that a wife’s death profoundly affects her husband (BT Sanhedrin 22b).

When Jacob blesses Joseph before his death, he tells his son (Gen. 49:25): “The God of your father who helps you, and Shaddai who blesses you […] blessings of the breast and the womb.” The Rabbis comment on this: Come and see how greatly Jacob loved Rachel. Even when he came to bless her son, he made him [Joseph] secondary to her. When he gives him “blessings of the breast and the womb” he is saying to Joseph: may the breasts that nursed such a son, and the womb that brought him forth, be blessed (Gen. Rabbah 98:20, [ed. Theodor-Albeck, MS. Vatican, 99:20, p. 1270]).

After Rachel’s death, Bilhah took her place. She raised Joseph and Benjamin as if she were their mother (Gen. Rabbah 84:11). Benjamin, who had just been born, needed a wet nurse; a miracle was performed for Bilhah and her breasts filled with milk, thus enabling her to nurse the newborn (Tanhuma, Vayeshev 7; see also the entry: “Bilhah”).

“Rachel Weeping for Her Children”

The Rabbis ask why Jacob buried Rachel “on the road to Ephrath,” and not in the Cave of Machpelah. They answer that Jacob saw with the spirit of divine inspiration that when the Israelites would set out to exile, they would pass through Bethlehem on the road to Ephrath, and so he buried Rachel there, so that she would pray for them. His prophecy was fulfilled, as Jer. 31:14–16 attests: “A cry is heard in Ramah—wailing, bitter weeping—Rachel weeping for her children, she refuses to be comforted for her children, who are gone. Thus said the Lord: Restrain your voice from weeping, your eyes from shedding tears; for there is a reward for your labor—declares the Lord: They shall return from the enemy’s land. And there is hope for your future—declares the Lord: Your children shall return to their country” (Gen. Rabbah 82:10).

Another exegetical tradition relates that when Rachel saw the events of the Destruction and the Israelites being sent into exile from their land, she jumped in before God and said: “Master of the Universe! it is known before You that Your servant Jacob’s love for me knew no bounds, and he worked for my father for seven years for me. When those seven years were completed and the time came for my marriage to my husband, my father advised exchanging me with my sister. This was exceedingly difficult for me, when I learned of this counsel. I informed Jacob, and I gave him a sign so that he could distinguish between me and my sister, so that my father would not be able to exchange me. After that I consoled myself, I suffered [to overcome] my desire and had compassion for my sister that she not suffer disgrace, and I gave her all the signs that I had given to my husband, so that he would think that she was Rachel. And this was not all—I went under the bed where he lay with my sister: he would speak with her, and I responded every time, while she remained silent, so that he would not recognize her voice. I acted kindly with her, I was not jealous of her, and I did not cause her to be shamed and disgraced. What am I, flesh and blood, dust and ashes, that I was not jealous of my rival wife, and that I did not allow her to be shamed and disgraced, but You, merciful living and eternal King, why were You jealous of idolatry that is of no import, and exiled my children who were slain by the sword, and allowed their enemies to do with them as they pleased?” God’s mercy was immediately revealed, and He said: “For your sake, Rachel, I shall return Israel to their place—for there is a reward for your labor […]. And there is hope for your future—declares the Lord: Your children shall return to their country” (Lam. Rabbah [ed. Vilna] petihtah 24). This midrash attributes a dual meaning to God’s statement: “for there is a reward for your labor.” Rachel acted in an extraordinary manner when she helped her sister to be married to Jacob and also when she prayed for her children. The midrash connects these actions, both of which express Rachel’s compassionate nature. Her compassion also succeeded in arousing God’s mercy when He answered her prayer.

To Whom Was the Birthright Given

The competition between Rachel and Leah did not cease upon Rachel’s death, and is reflected in the question of the birthright: which of the firstborn of Jacob’s wives would receive the birthright, Reuben or Joseph? In the Torah Reuben is deposed from his status as firstborn for having violated his father’s bed (Gen. 49:3–4) and this distinction is conferred on Joseph when Jacob declares that Ephraim and Manasseh are his sons (Gen. 48:5–6). Joseph thereby is awarded a double portion, which is the right of the firstborn. The midrash, however, presents two principal approaches to this question. According to one, Reuben, Leah’s son and the firstborn of Jacob, does receive the birthright. Deut. 21:15–17 prescribes that “If a man has two wives, one loved and the other unloved, and both […] have borne him sons […] he may not treat as first-born the son of the loved one in disregard of the son of the unloved one who is older. Instead, he must accept the first-born, the son of the unloved one, and allot to him a double portion of all he possesses.” The midrash compares this mandate with the story of Jacob. Of the two women that Jacob married, Rachel was loved, and Leah unloved. Both bore him children. When his time came to take leave of the world, he summoned his sons, but he did not choose Joseph instead of Reuben. Rather, he told the latter (Gen. 49:3): “Reuben, you are my first-born”; notwithstanding this, Jacob also spoke disparagingly of him (v. 4): “Unstable as water, you shall excel no longer.” Many years later, Moses would bless Reuben and release him from this disgrace (Deut. 33:6): “May Reuben live and not die.” This blessing expresses Reuben’s standing as firstborn, who took a double portion [as is the law of the firstborn]: “May Reuben live and not die”—“May Reuben live,” in this world; “and not die,” in the World to Come (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 13). This exposition emphasizes that Jacob acted in accordance with the commandment of the Torah and did not prefer the son of the loved wife to the son of the unloved one. Jacob gave Reuben the birthright, but it was postponed because of the sin of the latter, who was vindicated and regained his birthright in the time of Moses.

According to another exegetical approach, it is Rachel’s son who wins the birthright. The birthright should have come forth from Rachel, but Leah preceded her in [receiving divine] mercy; because of the former’s modesty, God restored the birthright to Rachel (BT Bava Batra 123a). According to this conception, Rachel’s son should from the outset have been the firstborn, but because God had compassion on the unloved Leah, He gave her the fruit of the womb and she bore Jacob’s firstborn son. Notwithstanding this, Rachel’s exemplary deeds caused the seniority to return to her. Continuing this exegetical orientation, in another midrashic depiction Jacob tells Reuben, while blessing his sons before his death: “The birthright was not yours. Did I not go to Laban only for Rachel? All the furrows that I plowed in your mother [i.e., acts of intercourse] should I not have done with Rachel? Now the birthright has returned to its owner” (Gen. Rabbah 98:4, [ed. Theodor-Albeck, MS. Vatican, 99:3, p. 1253]). According to this view, from the outset the birthright belonged to Rachel’s son, which was the intent of both God and Jacob. Due to Rachel’s good deeds or to Reuben’s sin, the initial order was restored. Another midrash adds that by merit of Rachel’s silence, two tribes—Ephraim and Manasseh—issued forth from her, in addition to the other ten tribes (Gen. Rabbah 71:5; Tanhuma, Vayeze 6). This midrash awards the birthright to Joseph, since his two sons became tribes and he therefore received twice as much as any of his brothers.

There is also an intermediate approach, which argues that Reuben should have received the birthright, but it was permanently taken from him because of his sin. Jacob told Reuben: “The birthright, the priesthood, and kingship were yours. Now that you have sinned, the birthright has been given to Joseph, the priesthood to Levi, and kingship to Judah” (Gen. Rabbah loc. cit.).

Although Rachel died young, the Rabbis indicate her positive influence on her descendants, even long after her passing.

Joseph

The Torah attests of Rachel (Gen. 29:17): “Rachel was shapely and beautiful”; and of her son Joseph (39:6): “Now Joseph was well built and handsome” [the two verses uses the same Hebrew phrases: yefat/yefeh to’ar, vi-yfat/yefeh mareh], to which the Rabbis apply the saying: “Throw a stick into the air, and it will [always] fall on its end” (Gen. Rabbah 86:6). This midrash indicates the physical trait shared by Rachel and Joseph, which the Bible expresses in identical language. The proverb teaches that we should not be surprised by this similarity, since Rachel was exceedingly beautiful, so was her son.

The midrash explains that the education that Joseph received from his mother continued to guide him even after her death. When Potiphar’s wife attempted to seduce Joseph, he raised his eyes and saw the image of his mother Rachel and was thereby saved from the sin of adultery (JT Horayot 2:5, 46[d]).

Benjamin, Saul and Esther

The midrash perceives Rachel as an educational figure who delineated the path that her offspring were to follow. She possessed the art of silence [when she knew that her sister was given to Jacob deceitfully, but remained silent and did not tell him]; all of her descendants continued in this path, and could keep a secret. Rachel’s son Benjamin knew about the sale of Joseph but did not reveal it to his father; therefore (Ex. 28:20) his tribe received the jasper [yashfe, with the meaning of yesh peh—there is a mouth] stone in the High Priest’s breastpiece. Saul, the son of Rachel’s son, remained silent (I Sam. 10:16) “but he did not tell him [his uncle] anything […] about [his being anointed for] the kingship.” Esther, who was descended from Rachel, was similarly reticent (Esth. 2:20): “But Esther still did not reveal her kindred or her people” and did not mention her Jewish origins in the palace of Ahasuerus (Gen. Rabbah 71:5; Tanhuma, Vayeze 6).

The midrash further states that, as reward for Rachel’s modesty, Saul was descended from her; and as reward for Saul’s modesty, Esther was descended from him. The Rabbis learned from this that when God decrees greatness for a person, He decrees greatness for all his posterity to the end of time (BT Megillah 13b).

Joshua

Joshua son of Nun was an Ephraimite, one of Rachel’s descendants. The midrash asserts that the salvation that occurred in his time in the war at Gilgal (Josh. 10:12): “Stand still, O sun, at Gibeon, O moon, in the Valley of Aijalon!” was by merit of Rachel’s kindness (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeze 18).

Elijah

The midrash records a disagreement among the Rabbis concerning the origins of Elijah. Some argued that he was from the tribe of Gad, while others maintained that he was a Benjaminite. Elijah came and stood before them. He said to them: “My masters, why do you disagree about me? I am from the descendants of Rachel” (Gen. Rabbah 71:9). This midrash is connected to the fundamental Rabbinic disagreement as to whether the harbinger of the Redemption will be from the offspring of Rachel or from those of Leah. Thus, we see that the rivalry between the two sisters did not come to an end but even pertains to the identity of the herald of the future Redemption.

Hadjittofi, Fotini, and Hagith Sivan. "Staging Rachel: Rabbinic Midrash, Theatrical Mime, and Christian Martyrdom in Late Antiquity." Harvard Theological Review 113, no. 3 (2020): 299-333.