Sephardic Food

Folio from the “Golden Haggadah,” created c. 1320 in Catalonia, Spain. From the collection of the British Library [Add MS 27210] (https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/golden-haggadah).

On each page are four miniatures which should be viewed in a particular order starting with the top right picture, followed by the top left image, then the lower right image, and lastly, the lower left miniature.

Sephardic food tells the story of the Spanish Jewish community from its roots in ancient Spain through the community’s expulsion in 1492 and subsequent global diaspora. Throughout the community’s history, its food has reflected its unique circumstances, whether as a protected minority in Muslim Spain or a demonized “other” in Christian Iberia. A profound connection existed between Sephardic women and Sephardic food; in each phase of the community’s existence, Sephardic women have acted as the main interpreters and preservers of this complex, delicious culinary repertoire.

Introduction

The pithy Ladino phrase “la mujer y la sartén en la kozina se yevan bien” (the woman and the frying pan get along well in the kitchen) is just one of many proverbs in the trove of Judeo-Spanish sayings and songs that speak to the deep connection between women and food in the Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic tradition. In the historical trajectory of Sephardic Jewry, from its days as a well-ensconced religious minority in the multicultural milieu of medieval Spain to its diasporic journey spanning the globe, women stand out as keepers of the community’s distinctive culinary identity.

The name “Sepharad” appears in the twentieth verse of the biblical book of Obadiah, and the early rabbinic sages took the name to denote the territory we now call Spain. Although in the popular imagination and for a not insignificant number of scholars, “Sephardic” means anything not Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi—that is, not Eastern European in extraction—here the term “Sephardic” is used specifically to connote those who can trace their heritage back to the Iberian Peninsula. A diverse array of non-Ashkenazi and non-Sephardic Jewish communities exists, each with its own delicious culinary repertoire representative of its distinct cultural and historical trajectory; the sumptuous, fruit-laden dishes of Persian Jews differ greatly from the spicy stews and fermented injera of the Ethiopian Jewish community and the long-cooked yeasted breads of Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi Jewish cuisine. Though Sephardic exiles from Spain interacted with these communities at various times and places, often inter-marrying both people and cuisines, the Sephardic community’s specific connection to Iberia involves unique cultural and culinary contexts that gave rise to what we now know as Sephardic food. This place-based association also allows for the inclusion of important contributions to Sephardic cuisine by certain communities that are Sephardic but not necessarily considered normatively Jewish—such as crypto-Jewish communities or the non-Jewish descendants of Sephardic Jews. The Sephardic diaspora is undeniably diverse, yet no matter how far people and dishes may have travelled from Spain, their Iberian roots are what makes them distinctly Sephardic.

Sephardic Food in Pre-Expulsion Spain

Evidence exists of a Jewish presence in Spain from as early as the third century BCE, when Spain was part of the Roman Empire. This proof of presence, however, gives no indication of what the Jews of ancient Spain may have eaten, nor the specific role of women in food preparation. Jews most likely ate from the abundance of crops available to them, especially in the Mediterranean climate of Southern Spain, including wheat, olives, and grapes. The Jews of Roman Spain most likely kept their contemporary version of the dietary laws of The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut. They probably ate a Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher version of what the Romans ate, such as garum, a fermented spiced fish paste that was a popular condiment in the Greco-Roman diet. Unfortunately, concrete evidence of the Jewish diet in pre-medieval Spain is scarce, and no more extensive from the period of Visigothic conquest of the Peninsula (roughly from the fourth to the eighth century CE).

From Visigothic legal rulings, however, we know of a definitive Jewish presence in Spain and the desire of the newly Christian Visigothic kings (officially converted to Christianity in 589 at the Third Council of Toledo) to regulate interactions between Christian and Jewish communities. It is reasonable to assume that Christian and Jewish communities frequently interacted and that a major aspect of that interaction was food-related, including eating and cultivating crops together or sharing a communal oven. Both Christian and Jewish sources from the time looked askance at this interaction because of the fear that commensality—eating together—could lead to intermarriage and a departure from each faith’s respective fold. Unfortunately, few clear sources delineate exactly what Jews in Visigothic Spain ate beyond bread, wine, and kosher meats.

A more clearly defined notion of Spanish Jewish food, which directly relates to our modern concept of the Sephardic culinary repertoire, began to emerge in the early medieval period. Starting in 711, the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, initiated by North African mercenaries and reaching its apex under the rule of the displaced Umayyad dynasty in Córdoba, significantly changed the religious composition of medieval Iberia and fundamentally altered the Peninsula’s culinary identity. At its height, roughly two-thirds of Spain was under Muslim rule. With this Muslim dominion came Muslim gastronomic inclinations, from specific crops and spices to the science of crop cultivation to cooking techniques and dining mores, all of which drew fundamental influence from the food of the Persian Empire (Zouali, Medieval Cuisine of the Islamic World). Ingredients such as eggplant, leeks, spinach, cucumbers, and garbanzo beans all began to enter the dishes of Sephardic Jews by way of this influence.

The Spanish Jewish community had special status as dhimmis (meaning they were second-class yet protected citizens of the caliph) and its members became involved in every aspect and level of medieval Spanish society. They were doctors, judges, viziers to caliphs and advisors to kings, merchants, farmers, poets, and philosophers, ushering in the Spanish Jewish Golden Age that lasted approximately from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. As Sephardim became more deeply involved within Muslim society, their culinary repertoire reflected the profound influence of a Muslim style of food preparation: the emphasis on certain colors (white and green, for their heavenly qualities), the use of certain ingredients (eggplant, sugar, vinegar, almonds), the serving of savory and sweet dishes at once, eating from a single communal dish. Of the 200 or so recipes from a thirteenth-century Andalusian cookbook, six are explicitly listed as Jewish, providing a window into what Muslim court culture viewed and served as Jewish food. They use many of the same ingredients as their Muslim counterparts, including eggs, almonds, mint, and more, but have some distinct Jewish characteristics: cooking over a low flame (a customary technique of Jewish Sabbath cooking), use of citron leaves (a citron is another word for “etrog,” the citrus fruit traditionally used in Lit. "booths." A seven-day festival (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei to commemorate the sukkot in which the Israelites dwelt during their 40-year sojourn in the desert after the Exodus from Egypt; Tabernacles; "Festival of the Harvest."Sukkot celebrations), and the technique of stuffing foods (a cooking technique connected to the celebration of Jewish holidays such as Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim). These recipes not only attest to the presence of Jews in the caliphal courts but certainly made their way into (if not were already prepared in) the homes of well-to-do Sephardic families as well.

Though few, if any, written sources connected to medieval Sephardic women remain, we can be sure they acted as the major keepers of hearth and home in the average Spanish Jewish domestic space. In the case of upper-class Sephardic women, as with their Christian and Muslim contemporaries, hired maids, often of different religions, provided the domestic and culinary labor of the house. Legal documents regarding the regulations of an open-air market in twelfth-century Seville indicate that Jewish women played a key role in purchasing food and most likely interacted with their Jewish and non-Jewish neighbors there, at the town communal oven, and at communal baths. They likely swapped neighborly gossip and even shared recipes.

Religious and Culinary Shifts in Medieval Spain

Beginning in the late fourteenth century, the religious balance of the Iberian Peninsula shifted drastically towards a Catholic majority with the onslaught of the Reconquista (literally, “reconquest”) from the Catholic north upon the Muslim south of Spain. With this religious reshuffling came a major geographic relocation of Jewish communities within Spain. The massacre of the Jews of Seville in 1391 triggered a series of violent massacres of Jewish communities across Spain, in addition to mass forced conversions of Jews to Catholicism. Though crypto-Jewish presence in the Peninsula dates back to Visigothic times, these mass conversions created a new community of secret Jews that, by a century later, was considered a serious nuisance by the Catholic monarchs, to the point that they and the Spanish Church established the Spanish Inquisition in 1478 to eradicate them from Spanish society. A main way to root out those Spaniards accused of Judaizing was through culinary evidence. Certain food practices were considered to definitively indicate specific religious identity; for example, “a preference for olive oil rather than pork fat raised suspicions of residual non-Christian practice” (Constable, 203). In this way, Inquisitorial records offer some of the clearest portraits of the medieval Sephardic culinary repertoire—the foods considered to be particularly “Jewish” by the Catholic Crown—including the use of olive oil, garlic, a preference for beef, certain vegetables such as eggplant, leeks, and garbanzo beans, and the eating of hard-boiled eggs (a common Sephardic practice at funerals). Many, if not a majority, of the people questioned by the Inquisition on account of their gastronomic proclivities were Sephardic women. Testimonies from such women as Vidueña Cohén, Aldonza Laínez, Catalina de Teva, Isabel González, and Juana Nuñez furnish modern readers, as they did Inquisitors, with a list of Sephardic Jewish recipes, from stews to salads to casseroles and more. (These recipes can be cooked today using David Gitlitz and Linda Kay Davidson’s cookbook A Drizzle of Honey: The Life and Recipes of Spain’s Secret Jews.)

With the conquest of Granada in 1492 by the Catholic monarchs, the seven centuries of Muslim presence on the Iberian Peninsula came to an end. The Catholic monarchs then issued the Edict of Expulsion of Jews from Spain. Among the reasons stated for their expulsion, food constituted a main rationale, specifically the sharing of “unleavened bread and meats ritually slaughtered.” Not only does this demonstrate what Catholics thought of as specifically Jewish foods—i.e., Unleavened bread traditionally eaten on Passover.mazzah and kosher meat—but the Edict of Expulsion also shows the perception of the profound connection between food and Jewish identity. Considered antithetical to the Catholic monarchs’ goal to “Castilianize and Christianize” Spain, any food substance remotely connected to any sort of Jewish identity was immediately suspicious. The court historian of the Catholic monarchs, Andrés Bernáldez, decades later continued to justify the decision to expel the Jews because, as he explained, the Jewish practice of frying meat in olive oil with onions produced a horrid “Jewish” odor.

Despite the Spanish crown’s best efforts, there continued to exist a longstanding community of crypto-Jews who retained their connection to Judaism through food. Without the ability to publicly observe Judaism through the reading of Jewish texts like the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah or engage in Judaism’s communal institutions, the home, and specifically food, became critical loci of continued crypto-Jewish practice of Judaism, with crypto-Jewish women at the helm; “with no Jewish community available to provide teachers, rabbis, schools, or texts, the only institution that remained more or less intact and viable was the family...the home transformed into the one and only center of crypto- Jewish life” (Melammed, 139), and at its center lay the kitchen. Moreover, “crypto-Jewish women sometimes observed Jewish rituals together with their husbands, but often they did so without their husbands’ or children’s knowledge. Mothers and grandmothers most frequently served as teachers; their concern with the past and the future is strikingly apparent” (Melammed, 140). One of the main ways crypto-Jewish women, often illiterate in Hebrew and untrained in liturgy, taught their children and grandchildren was through the practice of domestic rituals, specifically the preparation of ritual foods (see Medieval Spain). Accounts tell of crypto-Jewish women preparing matzah, or pan cenceño or pan ácimo (unleavened bread), in the night ahead of the Easter celebrations. In some cases, perhaps without knowing the Jewish origins of this bread, crypto-Jewish women also called it pan de Pascua, Easter bread. Often these breads were a biscuit-like torta, or cake, that adapted the strict The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah of matzah-making (where only flour and water should be used), with additions such as eggs, salt, and other ingredients. One particularly delicious recipe was from Angelina de Leon, who made her matzah in Castile in 1503 with white flour, olive oil, honey, and pepper (A Drizzle of Honey). (This recipe was quoted in the introduction to a 1997 New York Times review of Gitlitz and Davidson’s book, which inspired a new matzah company called 1503 Matzah in Portland that sells this medieval Spanish matzah.)

Preceding and following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, a large number (some historians reckon up to half of the Spanish Jewish population) relocated to Portugal, where non-Christians were ostensibly more welcome. This respite from expulsion and persecution, however, was quickly curtailed by the edict of expulsion of the Jews from Portugal in 1496 and the subsequent establishment of the Portuguese Inquisition in 1536. If the Spanish Inquisition was the main force diminishing the Sephardic converso community in the early sixteenth century, the Portuguese Inquisition had become the central eradicator of suspected Judaizing New Christians by its end. Indeed, as historians such as David Gitlitz write, by the time Spain annexed Portugal in 1580, the term “Portuguese” had become synonymous in the Iberian Peninsula and its colonies with “Judaizer.” Many of these Portuguese New Christians ultimately relocated to other parts of the world, including the Netherlands—where many of them would “re-convert” to Judaism— and Portuguese Goa—where the Goa Inquisition would later be established. At the same time, enough Portuguese New Christians remained in Portugal that two-fifths of the country’s current population can trace crypto-Jewish or New Christian lineage. In terms of the country’s food, this presence of Jewish converts to Christianity has left a meaningful impact, most notably on the number of foods that seem to be unkosher but actually are kosher, such as alheira (a sausage made with either beef or chicken, garlic, and paprika) and pasteis de bacalhau (cod fritters). Both of these dishes are still found in modern Portugal.

Spanish poetry and literature of this period further reveals the perceived identification between those of suspected Jewish heritage and specific culinary mores. In his Book of Food Love, the poet Juan Ruiz, Archpriest of Hita, writes that “some in their houses pass with two sardines;/In other residences they demand candies:/Cast aside the butcher, request adefinas. They said they would not eat pork without chickens.” Adafina, a long-simmering Sabbath stew that included beef, garbanzos, olive oil, onions, and other Jewish ingredients, was viewed as a particularly egregious example of Jewish cooking. In this time of the Old Christians’ growing concerns regarding New Christians’ blood (limpieza de sangre, literally cleanliness of blood), poets in the courts of Christian royals also engaged in a battle of wits in which they would attempt to lyrically implicate anyone they believed had Jewish heritage, most often using food in their poetic barbs. Some especially incriminating accusations included the consumption of almondrote, an eggplant and cheese casserole, at a nobleman’s wedding and the removal of pork products from their dishes, to which various cancioneros (song/poetic compilations) attest. Potentially hinting at her judeoconverso background, Dulcinea, the love interest of Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quijote, is said to have “the best hand at salting pork of any woman in La Mancha.” For a time, people from the city of Toledo in the south of Spain were derogatively referred to as berenjeros (“eggplant people”) because they were perceived to have blood “contaminated” by that of Muslims and Jews. Often, in this literary production, female characters are seen as most deeply associated with past and/or hidden Jewish identity through their preparation of certain foods.

Sephardic Dishes in Diaspora

The expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 initiated one of the farthest-reaching sub-dispersions of the greater Jewish diaspora, as Sephardic communities resettled in new and unfamiliar parts of the world. As the community split between the Eastern and Western Sephardic diaspora, it was dispersed across locations as diverse as Morocco, Italy, the Ottoman Empire, the Netherlands, and Curaçao and other Caribbean islands. No matter how quickly (or not) Sephardim assimilated into their new cultural contexts, their food reflected the changes in flavor brought on by their new residences. The post-1492 Sephardic culinary repertoire includes Curaçaoan Sephardic tutu (a cornmeal mush flattened in the shape of a plate and served with fried fish), Dutch Sephardic joodse boterkoeke (literally, Jewish butter cookie), Moroccan Sephardic zeilouk d’aubergine (eggplant relish), and impade, an almond-filled cookie typically eaten around Easter in Italy. Sephardic and crypto-Jewish families also played a fundamental role in colonizing the New World in early modernity and their presence can still be perceived in the flavors of popular North and South American street foods today, such as buñuelos (alternatively spelled birmuelos or bimuelos in the English transliteration of Ladino) in Mexico and bicotios (biscotti-like cookies, called biscochikos or biscotchos in Ladino) popular in New Mexico; the settlement of Dutch Sephardic Jews in the colonies of Recife in Brazil can be seen in the cuscus nordestino (“Northeastern” couscous, often made from coarse cornmeal in place of durum wheat or semolina). Elsewhere, too, the Sephardic presence influenced well-known dishes, such as fish and chips in England, widely believed to have come from the Sephardic Jewish manner of frying fish in olive oil, or pan di spagna (sponge cake) in Italy.

Throughout this resettlement, Sephardic women and their culinary preparations acted as ballasts in the vicissitudes of the early modern diaspora. Especially in the early days of the Sephardic diaspora in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when communities lacked traditional institutions of Jewish life such as the synagogue, the domestic and food-based aspects of Jewish life took on the critical role of connecting generations born in exile to the beloved Spanish and Portuguese homeland, even as it integrated the new ingredients of the places they settled. Judeo-Spanish songs such as “Siete Modos de Gizar Berengenas” (Seven Ways to Cook an Eggplant) and “Ke komiash duenya?” (What did you eat, lady of the house?) further attest to the undeniable association between Sephardic women and food, especially in the ex-Ottoman lands of Turkey, Greece (particularly the island of Rhodes), Macedonia, and the Balkans, from which these songs come. Just as Sephardic women preserved the Judeo-Spanish language of Ladino, which they taught to their children and grandchildren through these songs and often repeated refrains, so, too, did they pass on the vibrant dishes of the community’s cuisine. Ladino music, poetry, and stories (like the Folktales of Joha, Jewish trickster) tell tales of strong, beautiful, occasionally brash Sephardic women—aguelas, tiyas, madres e ijas (grandmothers, aunts, mothers, and daughters)—trying to bring order to their homes and sharing their love through the food they cooked. For instance, the nineteenth-century rabbi from Salonika (now Thessaloniki), Michael Molho, wrote fondly about his memories of his mother and aunts teaching his sisters how to make fideos, noodles, for desayuno, the major meal after Saturday morning services.

From all of these sources, we learn of the customs of the Sephardic hostess welcoming guests with a tavla de dulse (a silver platter with various chambers filled with preserved fruits like bimbriyo/quince, manzana/apple, and cayeçi/apricot), as well as a variety of bites such as borekas de kezo (cheese empanadas), yaprakes (stuffed grape leaves), keftes de prassa (leek fritters), and reshikas (thin sesame cookies), with a stiff drink of rakí, an anis-flavored liqueur, clouded by a drop of water. Sephardic brides were often said to be judged by the finesse with which they could prepare the “three B’s” of the Sephardic tradition: borekas (pastries with an oil dough stuffed with various fillings such as spinach, leek, cheese, or squash), boyos (small coils of filled dough, also spelled boyuz or boyoz), and bulemas (thick spirals of filled dough). Sadly, the upheavals and displacement of World War II and the Holocaust resulted in the tremendous loss of a great deal of the Sephardic heritage with roots in Turkey, Greece, and the Balkans, not to mention elsewhere in Europe.

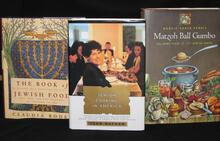

Luckily, however, the Sephardic community and its recipes persists today. Recently, there seems to be a growing fascination with Sephardic food culture as well as a proliferation of resources for Sephardic cooking, the majority of which are written and published by women. Perhaps the most notable example is Claudia Roden, author of the groundbreaking cookbook The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York. Other books, such as Dulce Lo Vivas and Recetas Endiamantadas by Ana Bensadón—with handwritten recipes from her relatives and family friends—are dedicated to the Moroccan Sephardic women who have ensured the continuation of their families’ culinary heritage. Blogs such as Bendichas Manos by Marcia Israel Weingarten, The Boreka Diaries (now The Global Jewish Kitchen) by Linda Capeloto Sendowski, and sephardicfood.com by Janet Amateau, testify to the growing online presence of Sephardic women in the food space. The linguistic revival of Ladino has also been shaped by the sharing of recipes, songs, and sayings, a mother tongue passed down from generation to generation by Sephardic women across the diaspora.

The influence of women on the Sephardic culinary repertoire cannot be understated. From pre-expulsion Spain into the contemporary global diaspora, Sephardic women hold the center of the Sephardic culinary repertoire. While it can be difficult to capture the many tastes of the Sephardic diaspora, it is surely women who have imbued it with undeniably Sephardic flavor.

Carrete Parondo, Carlos. Fontes Iudaeorum Regni Castellae II: El Triunal de La Inquisición En El Obispado de Soria. 1st ed. Fontes Iudaeoreum Regni Castellae 2. Salamanca: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, 1985.

Carrete Parondo, Carlos. Fontes Iudaeorum Regni Castellae III: Proceso Inquisitorial Contra Los Arias Dávila Segovianos Un Enfrentamiento Social Entre Judíos y Conversos. 1st ed. Fontes Iudaeoreum Regni Castellae 3. Salamanca: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, 1986.

Carrete Parondo, Carlos, and María Fuencisla García Casar. Fontes Iudaeorum Regni Castellae VII: El Tribunal de La Inquisición de Sigüenza, 1492-1505. 1st ed. Fontes Iudaeoreum Regni Castellae 7. Salamanca: Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, 1997.

Constable, Olivia Remie, ed. “39. Market Regulations in Muslim Seville.” In Medieval Iberia: Readings from Muslim, Christian, and Jewish Sources, 2nd ed., 227–31. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Constable, Olivia Remie. “Food and Meaning: Christian Understandings of Muslim Food and Food Ways in Spain, 1250–1550.” Viator 44, no. 3 (September 2013): 199–235.

“The Edict of Expulsion of the Jews - 1492 Spain.” http://www.sephardicstudies.org/decree.html.

Freidenreich, David M. Foreigners and Their Food: COnstructing Otherness in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Law. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011.

Foa, Anna. “The Marrano’s Kitchen: External Stimuli, Internal Response, and the Formation of the Marranic Persona.” In The Mediterranean and the Jews: Society, Culture and Economy in Early Modern Times, edited by Moises Orfali. Bar-Ilan University Press, 2002.

Koen-Sarano, Matilda. Folktales of Joha, Jewish Trickster. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2010.

Marks, Gil. Encyclopedia of Jewish Food. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010.

Lieberman, and Lieberman, Julia Rebollo. Sephardi Family Life in the Early Modern Diaspora. HBI Series on Jewish Women. Hanover: Published by University Press of New England, 2011.

Melammed, Renée Levine. Heretics Or Daughters of Israel?: The Crypto-Jewish Women of Castile. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Molho, Michael. Traditions & Customs of the Sephardic Jews of Salonica. Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture, 2006.

Roth, Cecil. Doña Gracia of the House of Nasi. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1977.

Ruiz, Juan. Libro de Buen Amor. 12th ed. Colección Austral 98. Madrid: Editorial Espasa-Calpe, S.A., 1970.

Zaouali, Lilia, and Charles Perry. Medieval Cuisine of the Islamic World: A Concise History with 174 Recipes. Translated by M. B. DeBevoise. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press, 2009.

Cookbooks:

Angel, Gilda. Sephardic Holiday Cooking: Recipes and Traditions. Mount Vernon, NY: Decalogue Books, 1986.

Bensadon, Ana. Recetas Endiamantadas. Alcobendas, Madrid: Toy Story, 2013.

Clabrough, Chantal. A Pied Noir Cookbook: French Sephardic Cuisine from Algeria. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2005.

Cohen, Stella. Stella’s Sephardic Table: Jewish Family Recipes from the Mediterranean Island of Rhodes. Cape Town, South Africa: Hoberman Collection, 2012.

Goldstein, Joyce. Sephardic Flavors: Jewish Cooking of the Mediterranean. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000.

Kaufman, Sheilah. Sephardic Israeli Cuisine: A Mediterranean Mosaic. New York: Hippocrene Books, 2002.

Marks, Copeland. Sephardic Cooking: 600 Recipes Created in Exotic Sephardic Kitchens from Morocco to India. New York: Penguin Group (USA) Incorporated, 1994.

Milgrom, Genie. Recipes of My 15 Grandmothers: Unique Recipes and Stories from the Times of the Crypto-Jews During the Spanish Inquisition. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House Limited, 2019.

Morse, Kitty, and Danielle Mamane. The Scent of Orange Blossoms: Sephardic Cuisine from Morocco. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2001.

Roden, Claudia. The Book of Jewish Food: An Odyssey from Samarkand to New York. 1 edition. New York: Knopf, 1996.

Sisterhood, Sephardic Temple Or Chadash. Sephardic Heritage Cookbook: Ottoman, Persian, Moroccan, Egyptian Recipes and More. North Charleston, South Carolina: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017.

Sternberg, Robert. The Sephardic Kitchen: The Healthy Food and Rich Culture of the Mediterranean Jews. Harper Collins, 1996.

Trock, Beyhan Cagri. The Ottoman Turk and the Pretty Jewish Girl. United States. Cupper James Publishing, 2012.

Twena, Pamela Grau. The Sephardic Table: The Vibrant Cooking of the Mediterranean Jews: A Personal Collection of Recipes from the Middle East, North Africa, and India. Houghton Mifflin, 1998.