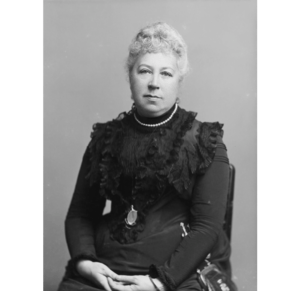

Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea

A member the aristocratic Rothschild family, Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea, inherited her mother’s strong sense of duty to the poor, an independent spirit, and social entrée to the topmost echelons of English society. Battersea was active in English philanthropy, the temperance movement, the women’s suffrage movement, and the movement for reforms of women’s prisons. She founded the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women in 1885, and in 1902 she convinced the Union of Jewish Women to ally with the National Union of Women Workers and the International Council of Jewish Women. By bringing Jewish women into the English women’s movement, Battersea helped lay the basis for the formation of a distinctively Jewish women’s movement in England.

Family and Early Life

Constance Rothschild Lady Battersea (1843–1931), and her sister Anne (1844–1926) were the daughters of Baron Anthony (1810–1876), and Louise (nee Montefiore, 1821-1910) de Rothschild. Her father was a scion of the wealthiest and most distinguished Jewish banking family in England. The Rothschilds enjoyed pre-eminence among the network of aristocratic cousins who ruled Anglo-Jewish society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Raised in a traditional Jewish household, Constance and Anne inherited their mother Louise de Rothschild’s strong sense of duty to the poor, an independent spirit, and social entrée to the topmost echelons of English society. As young girls they taught in the village schools surrounding their home and at the Jews’ Free School for the poor in London. Together, the girls wrote a popular children’s book entitled The History and Literature of the Israelites, which was highly praised by Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli.

The elite social circle of the Rothschild daughters, who were raised in a home where their parents entertained the leaders of English politics and society, included both Christians and prominent Jews, with the Rothschilds being connected by blood or marriage to the majority of Anglo-Jewry’s most notable families. However, Constance and her sister Anne both married Christians, despite their parents’ acute unhappiness. Constance married Cyril Flower (1843–1907), later Lord Battersea, in 1877, while Anne married Eliot Yorke in 1873. Both marriages were childless.

Marriage

Although Constance’s marriage to Cyril Flower was controversial due to Flower’s gentile background, it would prove a happy, if somewhat unconventional one. Cyril Flower, Lord Battersea, generally preferred the social and romantic company of other men, and Constance was apparently aware of this situation even before a more public scandal involving Battersea and a male lover in 1902. However, Cyril’s marriage to Constance was characterized by warm friendship, shared interests, and a deep intellectual respect on both sides. Both were passionate supporters of Britain’s Liberal Party; until the 1902 scandal forced him into retirement, Cyril enjoyed a successful political career, aided by Constance’s keen social sense and strong network of powerful friends. Both aristocrats from birth, Constance and Cyril were further united by a shared interest in the welfare of the poor and working class of England, which informed their political and charitable work, including Constance’s interest in socialist-leaning organizations and her work on prison reform.

The Rothschild daughters’ marriages and strong social ties to the gentile aristocracy undoubtedly contributed to Constance’s complicated relationship with Judaism as a religion. She explored her own spirituality and religious beliefs throughout her life, attending Christian church services and considering baptism at one point (although this never materialized), but she always retained a sense of Jewish heritage and identity; even at the times in her life when she regularly attended church and professed sympathy for Christian theology, she referred to Jewish holidays in her personal diaries as “ours.” Disillusioned with Orthodoxy, Constance felt some sympathy for the new Liberal Judaism that emerged at the turn of the twentieth century, but she never joined the movement.

Social Activism

After her marriage, Battersea combined a lavish social life with charitable activities. Profoundly committed to the social concern instilled in her by her mother, she became active in English philanthropy, including royal projects, and then became engaged in the temperance movement that flourished in England and America in the mid- and late- nineteenth century. While much of the temperance movement had been started through Christian churches, the movement itself was not religious, and Battersea was inspired by the cause. Further, the temperance movement, although heavily influenced by Christian ideology, presented itself as one for the betterment of society as a whole, rather than any one group, class, or nationality. As a result, Battersea joined the British Women’s Temperance Association in the 1890s and eventually became a leader of temperance campaigns in London and the provinces. Battersea was introduced to the women’s movement in 1881 by suffragist and temperance worker Fanny Morgan, whom Battersea helped to undertake a political career that resulted in her election as mayor of Brecon.

In the mid–1890s, Battersea’s reputation for social activism, as well as her close friendship with Morgan, already an activist, led her to become active in the movement for reforms of English women’s prisons, which were chaotic, unhealthy, and often cruel. Most working-class Jews who became criminals were boys or men who were usually involved only in petty crime. Indeed, Battersea met only three Jewish female convicts during her visits to Aylesbury prison. However, her interest in prison reform stemmed not only from a Jewish perspective but also from one of social activism, and particularly women’s activism. In fact, she eventually became a government-appointed member of the board of Aylesbury Women’s Prison as part of broader reform efforts.

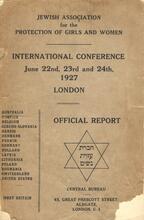

Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women

In 1885, Battersea became involved in the anti-sex-trafficking and so-called “rescue work” movement, after learning of a need for “rescue” services from a specifically Jewish perspective. Jewish prostitutes looking to leave sex work were, according to stories that reached Constance, hesitant to seek help from existing organizations, which were run by Christian missions and which the women believed would try to convert them. Horrified, Battersea engaged many among the liberal leadership of Anglo-Jewry in the fight to rescue Jewish prostitutes by founding the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women (JAPGW). The mixture of Jewish traffickers and Jewish victims, she believed, demanded the creation of a distinctly and explicitly Jewish organization.

To create the JAPGW in 1885, Battersea had to overcome the resistance of the organized Jewish community, which was reluctant to admit that Jewish prostitution existed in England. She also had to overcome English feminists’ resistance to accepting Jewish women, and to pre-existing stereotypes that “rescue work” was unsuitable for public discussion by women, as it dealt with women who were perceived as outside the realm of respectability. Battersea’s own feminism, superior class status and her membership in the royal circle helped overcome initial resistance by both Jewish, and feminist opponents. In fact, only a few years after its founding, the JAPGW would be celebrated by both Jewish and gentile writers and critics for its extensive and multi-national scope of work.

The JAPGW expanded its work from Britain, which was serving at the time as a “transfer point” for sex trafficking, to broader activism in Europe and South America. It focused especially on Argentina, a “final destination” for many trafficked women, who had been persuaded, often through phony offers of marriage, to leave their homes in Eastern Europe to travel onward with their traffickers. Aware that active engagement with potential victims and their traffickers at points of contact would be considered unsuitable for women, the JAPGW created a men’s auxiliary, headed by Claude Montefiore, which engaged in direct work at the docks where trafficked women landed, in an attempt to engage them and provide them with refuge at the earliest possible point. This involvement of prominent men soothed any concerns about the respectability of ladies on their own engaging in rescue work, while simultaneously drawing publicity to the movement. That being said, the JAPGW was careful to remain an organization first and foremost by and for women, in keeping with Battersea’s interest in the rights of women on a broader scale.

National and International Feminism

Feminist detractors were further won over by Battersea’s friendship with leaders of the International Council of Women, which provided social entrée into the National Council of Women Workers and the class-conscious women’s movement. Constance Battersea’s work in temperance, prison reform, and white slavery had drawn her into the English woman’s movement by the 1890s. She was introduced to the National Union of Women Workers (NUWW) of Great Britain and Ireland (later the National Council of Women of Great Britain and Ireland), which became the umbrella organization for all women’s philanthropic groups in Great Britain.

Battersea joined the NUWW’s Executive Committee and was elected vice-president in 1896; she served as president in 1902 and 1903 and on the executive committee until 1919, when she was made an Honorary Vice President. Throughout this period, she energetically brought Jewish women into the Union, encouraging them partly for the opportunity the organization afforded middle-class women to become active outside the home, partly to help less fortunate women, and partly because she—and other Jewish communal leaders—saw membership as a sign of social acceptance for Jews.

Battersea’s NUWW leadership further involved her in the international women’s movement. From 1899 and throughout her life, she was a delegate at successive Congresses of the International Council of Women (ICW). By her status as a delegate, Battersea indicated a concern with feminist issues that extended beyond strictly Jewish interests. In fact, her work with the NUWW and ICW can be seen as yet a further extension of her broader feminist and charitable interests, as was her work on prison reform, Liberal Party activism, and friendship and collaboration with Fanny Morgan.

Still, she worked tirelessly to bring Jewish women into the organization and to bring Jewish concerns to the attention of ICW leadership. In 1902, she persuaded the new Union of Jewish Women (UJW) to ally itself with both the National Union of Women Workers and the ICW. Battersea’s prominence in the NUWW and the ICW signaled an important crack in English and international feminism’s monolithic Christian façade and drew significant numbers of Jewish women into the English women’s movement, as did the subsequent successes of the UJW within the Jewish community. Jewish women’s involvement ultimately helped to broaden the movement’s political base, thereby strengthening English feminism.

By bringing Jewish women into the English women’s movement, Battersea helped lay the basis for the formation of a distinctively Jewish women’s movement in England. The feminist focus was heightened because her creation of the JAPGW in 1885 engaged Jewish women in profound activism on behalf of less fortunate sisters, further influencing the emergence of conscious Anglo-Jewish feminism.

Battersea’s JAPGW had identified itself with women’s movement goals, becoming the first Jewish organization to publicize the exploitation of prostitutes and rescue women forced into white slavery. In the process, it became the first Jewish organization to bring sensitive issues of concern to women to the popular consciousness. Battersea became a link between English and Jewish feminism, as she convinced numbers of upper-and middle-class Anglo-Jewish women to join English feminist groups like the NUWW and encouraged them to create Jewish women’s organizations, such as the Union of Jewish Women, which allied themselves with the women’s movement.

The Rothschild sisters, who were so close in life, died only a few years apart: Anne in 1926 and Constance in 1931, on the anniversary of her marriage to Cyril. Both were buried in London, at the Willesden Jewish Cemetery.

Battersea, Lady Constance. Reminiscences. London: Macmillan, 1922.

Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women. Annual Reports. 1895–1933.

Battersea Papers at the Rothschild Family Archive in the City of London.

Cohen, Lucy. Lady De Rothschild and Her Daughters. 1821–1933. London: John Murray, 1935.

Davis, Richard. The English Rothschilds. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1983

Jewish International Conference on the Suppression of the Traffic in Girls and Women. Official Reports. 1910, 1927.

Kuzmack, Linda Gordon. Woman’s Cause: The Jewish Woman’s Movement in England and the United States, 1881–1933. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1990.