Lady Louise Rothschild

Lady Louise Rothschild and her husband Sir Anthony Rothschild both came from a distinguished line of Anglo-Jewish aristocracy. Due to her unrivaled social status, Lady Rothschild was able to flout conventions which traditionally restricted Jewish women to the home in England. Thus in 1840 she founded the first independent Jewish women’s philanthropic associations, inspiring upper- and middle-class Anglo-Jewish women to venture outside the home and into public life for the first time. Lady Rothschild combined traditional Jewish concepts of zedakah with “scientific” methods of charity – her organizations encouraged the Jewish poor not to ask for handouts but to cultivate thrift, self-sufficiency, and a reverence for the upper classes. In 1885, Lady Rothschild established the first Jewish working girls’ club for immigrants, which set a precedent for the socialization of immigrant and working Jewish girls.

Lady Rothschild’s Unrivaled Social Status

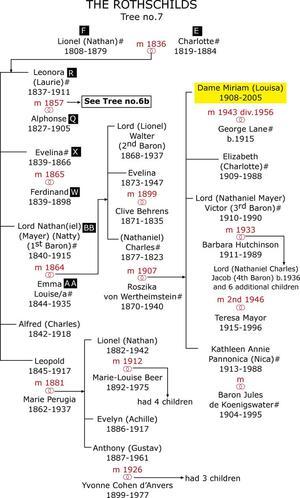

Lady Louise Rothschild came from a distinguished line of Anglo-Jewish aristocracy. Her father, Abraham Montefiore (1788–1824), was the brother of Sir Moses Montefiore (1784–1885). Her mother, Henrietta (1791–1866), was the daughter of Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812). Her husband, Sir Anthony Rothschild (1810–1876), was the son of Nathan Mayer Rothschild (1777–1836), himself the son of Mayer Amschel Rothschild. Anthony and Louise had two daughters: Constance Rothschild Battersea (1843–1931), who married Cyril Flower, First Lord Battersea (1843–1907), and Annie (1844–1926), who married Eliot Yorke (1843–1878) of the earls of Hardwicke.

Lady Rothschild launched Anglo-Jewish women into organized philanthropy when she founded the first serious volunteer philanthropic organization of Jewish women in Victorian England. In so doing, she inspired many upper- and middle-class Anglo-Jewish women to emerge out of the home and into public life for the first time.

Lady Rothschild’s position as the wife of Baron Anthony de Rothschild, a scion of the pre-eminent banking family, gave her an unrivaled social status that enabled her to risk scandal by flouting conventions that restricted Jewish women in England, as elsewhere, to the confines of the home. Traditionally, Jewish women remained within the home and did not venture into the public arena. This attitude meshed well with mid-nineteenth-century English attitudes that emphasized the critical importance of women maintaining an exclusively domestic role to support a vital home life.

Philanthropic Works

Jewish women who engaged in public activity therefore risked criticism from Jews and non-Jews alike. While British Jews enjoyed many opportunities unavailable elsewhere in Europe, particularly in business, they were still subjected to a strong social antisemitism, economic restrictions, and legal and political discrimination. Adding to the risk, Lady Rothschild and her female cousins were stepping into public philanthropy at the height of Anglo-Jewry’s fight for political emancipation, led in great part by Rothschild men and their upper-class cousins. The stern opposition faced by the Jewish community increased the danger for women in public life.

Lady Rothschild’s background made her innovations possible. Wealthy, cultivated, well-educated and imbued with a powerful sense of religion and moral obligation, she focused her life around duty and service to others. She became famous for a range of philanthropic works, from nursing sick villagers to founding village schools to participating in the management of the Jews’ Free School for poor children.

Expanding the range of her service, Rothschild launched Jewish women into organized philanthropy in 1840 when she founded the first independent Jewish women’s philanthropic associations, the Jewish Ladies’ Benevolent Loan Society and the Ladies’ Visiting Society. These benevolent societies were among many charitable organizations established by Jewish communities in England to assist and acculturate the Jewish poor.

Philanthropic Method

Keenly aware of being a vulnerable minority, both as Jews and as women, Louise Lady Rothschild and her cousins took care to engage in charitable activities similar to those of their Christian peers. Many Christian women had already ventured into philanthropic organizations, justifying their activities by developing a “cult of domesticity” that viewed women’s philanthropic activity as a public extension of their moral influence upon the home.

Following this pattern, Lady Rothschild’s Benevolent societies combined traditional Jewish concepts of Lit. "righteousness" or "justice." Charityzedakah with “scientific” methods of charity found in Octavia Hill’s Charity Organization Society, then Britain’s pre-eminent Christian charitable organization. The society waged a campaign against impulsive charity, believing that it fostered inefficient administration and encouraged the poor to lie in order to receive funds. Instead, volunteers were trained to encourage their clients to become independent through thrift and self-help.

Based on this model, Lady Rothschild’s societies became the “first link in the chain” to unite London Jewry’s upper-class West End with the working-class East End, according to the London Jewish Chronicle. The societies’ executive councils were led by a bastion of Rothschild women, providing an underlying structure of female relatives and friends, typical of the female friendships of the nineteenth century. Similar to the Christian model of charitable organizations, Lady Rothschild’s benevolent societies’ volunteers, or “friendly visitors,” examined the home conditions of families seeking assistance, gave personal advice and tried to determine the most effective manner of providing philanthropic help. The Jewish poor were urged to cultivate thrift, self-sufficiency and a reverence for the upper classes, so that they might be considered worthy English citizens. Not surprisingly, working-class Jewish women often resented this condescension.

The First Jewish Working Girls’ Club

Always concerned for her “less favoured sisters,” Louise Lady Rothschild initiated and financed programs for immigrant girls after thousands of East European immigrant Jews flooded England form 1881 onwards. In 1885 Rothschild created the first Jewish working girls’ club for immigrants, the West Central Friday Night Club. Led by a professional social worker, West Central developed an extensive program serving a variety of social, educational, and recreational purposes.

West Central created a furor, stimulating a debate between opponents who argued it took girls away from their families during their leisure hours, and supporters who maintained that the club kept girls away from the temptations of cheap music halls and “tawdry entertainments” in favor of more wholesome society. Despite the clamor, West Central established what became a pivotally important, communally acceptable precedent for socializing immigrant and working girls. From the mid–1890’s through the middle of the twentieth century, directorship of the club passed to social worker and Liberal Judaism’s founder, Lily Montagu, who transformed West Central from a relatively small group into Anglo-Jewry’s premier girls’ club and settlement house.

Legacy

Lady Rothschild’s leadership endowed Jewish women’s philanthropic organizations of the era with an unrivaled social cachet that empowered upper-and middle-class Anglo-Jewish women to create a plethora of charitable groups. Similar to Christian women’s philanthropic model, Lady Rothschild’s societies gave women a consciousness of their identities as women, developed a sense of group identity and trained women in organizational skills.

Following Lady Rothschild’s example, Jewish women adjusted the Christian model to a Jewish framework, creating their own women’s organizations that focused upon their own concerns. The success of Jewish women’s benevolent societies laid the groundwork for the emergence of England’s first politically oriented Jewish feminist movement, in which Lady Rothschild’s daughter Constance Lady Battersea was to play a prominent role.

Bermant, Chaim. The Cousinhood. New York: Macmillan, 1971.

Cohen, Lucy. Lady de Rothschild and Her Daughters, 1821–1931. London: Murray, 1935.

Davis, Richard. The English Rothschilds. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 1983.

Gordon Kuzmack, Linda. Woman’s Cause: The Jewish Woman’s Movement in England and the United States, 1881–1933. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 1990.

Lipman, V. D. Three Centuries of Anglo-Jewish History. London: N.p., 1971.

Summers, Anne. Christian and Jewish Women in Britain, 1880-1940: Living with Difference. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.