Elza Niego

In 1927, Elza Niego, a young Jewish woman working at an office in Istanbul’s Galata neighborhood, was stabbed to death in broad daylight on a busy street. Her murderer was an older Turkish man who had confessed his love to her and whose advances she had repeatedly refused. Her murder sparked an intense emotional reaction in her community, and her funeral attracted hundreds of Jews to the streets. The Turkish press claimed Jews had flocked to the streets, blocking traffic and yelling calls for justice. Jewish public outrage was unacceptable, seditious, and ungrateful. The press reaction led to the arrest of nine Jewish leaders and the curtailing of the Jews’ right to free travel in Turkey. Niego’s murder was an early indicator of the new government’s determination to quash any public Jewish expression.

Life and Murder

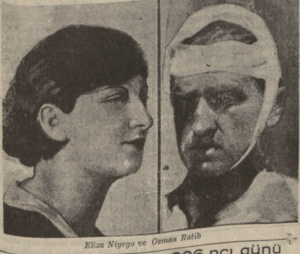

Elza Niego (sometimes Elsa Niyego) was a young Jewish woman born in Istanbul in 1909[JS1] (exact date unknown). When Niego was seventeen, Osman Ratip Pasazade (sometimes wrongly identified as Ragip), a Turkish Muslim man in his 50s, took notice of her. Some accounts say Osman Ratip, the son of Ahmet Ratip Pasa, former Ottoman governor of the Hijaz, became infatuated with her after seeing her on Buyukada, an island close to the city where many Jews and well-off Muslims vacationed. Some accounts claimed he was friendly with the Niego family patriarch Izak on the island and hence met his daughter.

For a long period, Osman Ratip professed his love repeatedly, even asking Elza’s family to marry her, to which both Elza and her family said no. After his insistent stalking and threats, the Niego family complained to the police, which led to a jail term for Osman Ratip. After his release, perhaps after hearing that Elza Niego was engaged, Osman Ratip stabbed her to death on August 17, 1927, in broad daylight on the busy Bankalar Street in Galata, near her office where she worked at an insurance company (or bank according to some). Her sister Regine was also injured by some accounts. Niego died at the young age of eighteen.

The Murder’s Aftermath: Show Trials

Elza Niego was an educated young Jewish woman from a well-to-do family. She had been educated in European languages and worked outside the home doing clerical work. It was her shocking murder that made her a communal cause célèbre, and even more so the repressive response from Turkish state and society.

Initially, Turkish press coverage of the unfortunate murder of this young and “beautiful” woman was sympathetic. Her well-attended funeral was held the day after her brutal murder. During the funeral, the crowd filled the street, blocking the passage of a truck that had to wait for the procession to clear out. According to Turkish press reports following the funeral, the Jews gathered to remember her turned the funeral into a demonstration. They called for justice for Elza from the government and Turks. Mourners blocked traffic and hassle police officers.

To the Turkish press, all this amounted to an unacceptable public demonstration of Jewish outrage. The authorities sprang into action on August 20, arresting nine Jews, including David de Botton, Daniel Carasso, Norbart Leytes, Leon Yeuda (Madjar), Rahamim (Haim) Levy, and Nisim (Ben David) Eskenazi. Alongside these supposed ringleaders, some of whom had leadership positions in Jewish communal institutions, the police arrested Avraam Korido, a Jewish soldier who had supposedly threatened a man named Şükrü during the funeral. These nine men were charged with obstructing police, incitement, and breaking laws on demonstrations. Some reports state the men were also charged with insulting Turkishness, a bona fide crime.

While the trial for these Jewish men was being orchestrated, Elza’s murderer Osman Ratip Pasazade had been deemed criminally insane and remanded to an asylum instead of being convicted for murder and sent to prison.

The accused Jews’ request to be released on bail was denied and they were jailed for the duration of the trial, which began on August 27, 1927. They were represented by the Jewish lawyer Ibrahim Nom (formerly Avram Naon). The defense was able to show that two police officers present at the scene did not record any of the claims in the prosecution case in their original reports, but rather only added them in an additional report they wrote following the Turkish press’s outcry about Jewish sedition, and they could not explain this and other inconsistencies. During the initial proceedings, the defense also presented an alibi for and was able to secure the release of Leon Yeuda (Madjar), a dentist, who had been busy seeing patients and had not even attended the Niego funeral.

On August 29, 1927, limitations on domestic travel, which had thus far only been applied to Armenians and Greeks, were expanded to include Jews, and this expansion was reported in the local press. Freedom of travel would be restored in November 1927. This was no coincidence: many Jews saw it as punishment for the calls for justice for Elza.

The trial of the supposed Jewish instigators began in earnest in September 1927. The court heard the testimonies of the journalists who had started the accusations, and the newspapers’ anti-Jewish campaigns continued. Jak Pardo, an elderly Jewish teacher, wrote a letter to his former student Prime Minister Inonu during the trial, complaining of maltreatment of the Jews, which led him to be arrested for contempt of court.

As the prosecutor complained in court about Jews not speaking Turkish enough in public life and being ungrateful, it was evident to all involved that this was a show trial regarding the Jews’ national loyalty to Turkey. The case did not hinge on the facts specific to the funeral of Elza Niego. Looking for evidence of an organized anti-Turkish contingent, the police investigated the Chief Rabbinate and other Jewish communal institutions and interviewed prominent Jewish businessmen and communal leaders like Albert Karaso and Marko Nahum. And the anti-Jewish campaign that was sparked by Elza’s funeral was not strictly local. In Izmir, the local Turkish press relentlessly published anti-Jewish screeds, a young Jew was arrested after brawling with a man who hassled him for speaking Ladino, and local teachers organized a petition protesting against Jews, including a call for taking down Hebrew signage at the Jewish hospital and rabbinate—which an anti-Jewish mob promptly did.

On September 20-21, the court decided to release Jak Pardo and the original arrestees, who had been in prison for 33 days. Deciding that the soldier Avraam Korido had in fact attacked his accuser Şükrü, the court sentenced Korido to 35 days in prison, with 33 already served. The press reported that Prime Minister Inonu had written to the prosecution praising his former teacher Pardo and claiming that he had never received Pardo’s letter.

Avner Levi, a prominent historian of Jews in the Republic of Turkey, characterizes this month-long episode as the peak of an anti-Jewish campaign that had simmered since 1922. Afterwards, Jews were cowed into limiting their visibility in public, fulfilling the onslaught’s goal. Immediately after the trial, notable works of Jewish apologia were published by prominent Jewish writers such as Muhsin Tekinalp (formerly Moiz Kohen) and Avram Galante.

Remembering the Trials

The murder of Elza Niego and the trial of numerous Jews that followed were remembered by both the Jewish community and the Istanbul press. On May 19, 1937, Elza’s killer Osman Ratip was himself stabbed to death by another patient in the asylum in which he had been confined. Many Turkish newspapers covered Osman Ratip’s death, recounting the tragic murder of the young Niego and only curtly mentioning the ensuing show trial, without reference to the antisemitic press campaign that had engendered it.

The trial had also made a major impression on Jews, who remembered it as a cautionary tale against demanding justice in Turkey–which had only brought more repression. The presiding judge of the 1927 show trial, Hasan Lutfu Orser, was fondly remembered in the October 15, 1940, issue of the Jewish biweekly La Boz de Turkiye for his fair conduct and ruling in the case, in what was a rare obituary for a non-Jew in a Jewish publication. The trial was also memorable enough to be marked in an obituary for Ibrahim Nom, the lawyer for the defendants, a poet, and a communal leader. The Jewish memory of the Elza Niego affair, as La Boz called it, was focused on the proven innocence of Jews against accusations of disloyalty, while Turkish memory centered on the unfortunate death of a young girl, minimizing the surrounding politics.

Levi, Avner. Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nde Yahudiler. Istanbul: Iletisim, 2010.

Üstün, Ebrar Begüm. “Erken Cumhuriyet Dönemi Kadın Cinayetlerinin İstanbul Gazetelerine Yansıma Biçimleri (1923-1945).” Unpublished master’s thesis, Yildiz Technical University, 2020. http://dspace.yildiz.edu.tr/xmlui/handle/1/12656

Periodicals: La Boz de Turkiye 1939-1949, Haber and Tan 1937.