Michal, daughter of Saul: Midrash and Aggadah

Michal, daughter of Saul, married David. In love with David, Michal proved her loyalty to her husband over her father when she saved David from her father’s attack on his life. In the Midrash, Michal is praised for her loyalty to her husband and her rejection of her father’s authority. When Michal later disrespected David publicly, she was punished with a prophecy that to her dying day she would have no children. The Aggadah recounts that Michal had a son on the day she died. When her sister Merab died, Michal raised her five children as her own.

Michal’s Marriage to David

Michal was Saul’s younger daughter, who fell in love with David and married him for one hundred Philistine foreskins. According to the Bible, Merab, Saul’s older daughter, was to have married David, but she was given in matrimony to Adriel the Meholathite, while David married Michal. Despite the Biblical account, some Rabbis assert that David married both of Saul’s daughters. The Rabbis ask how David could have married two sisters, an act that is prohibited by the The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah, and answer that David first married Merab, and married Michal after her death (T Suspected adulteressSotah [ed. Lieberman] 11:18). A different Rabbinic position, however, denies that David married Merab (BT Sanhedrin 19b).

The Rabbis present Michal as a beautiful woman, who was lusted after by all who saw her (BT Lit. "scroll." Designation of the five scrolls of the Bible (Ruth, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The Scroll of Esther is read on Purim from a parchment scroll.Megillah 15a). They claim that she was David’s favorite wife and was therefore called “Eglah” (calf), because she was as beloved to him as a calf. Eglah, the name of one of David’s wives, is mentioned in II Sam. 3:5. The identification between these two wives of David—Eglah and Michal—resulted from the desire of the Rabbis to limit the number of David’s wives. The Torah (Deut. 17:17) mandates that the king “shall not have many wives”; the maximum number permitted to a king under this rule, according to the Rabbis, is eighteen. II Sam. 3:2–5 records that David had six wives when he was in Hebron: Ahinoam of Jezreel, Abigail wife of Nabil the Carmelite, Maacah daughter of Talmai, Haggith, Abital, and Eglah. Afterwards, the prophet Nathan tells him (II Sam. 12:8): “I would give you twice as much over,” which the Rabbis understand to mean that the number of wives that David already had would be tripled: from six to eighteen. Since Michal was not included in the list of his first six wives, but was already married to him before this statement by the prophet, the Rabbis identified Eglah with Michal. They interpreted “Eglah” as an appellation, rather than a proper name, and gave it various meanings; for additional understandings of this appellation, see below (BT Sanhedrin 21a).

Loyalty to David

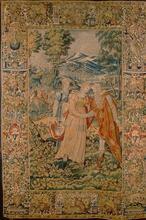

The Book of Samuel relates that Michal and Jonathan loved David and protected him from their father’s evil designs. Expanding on this, the A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).Midrash states that Michal saved David from danger within the house, and Jonathan, from external danger, and applies to them the verse (Eccl. 4:9): “Two are better than one” (Midrash Tehillim 59:1). Expanding on the Biblical account (I Sam. 19:11–17) of how Michal aided David to flee when her father sought to kill him, the Rabbis tell of Michal’s wise actions in saving her husband’s life and the intelligent manner in which she withstood her father’s rage. To avoid Saul’s guards, who were stationed at the entrance to the house to prevent David from escaping, she let David down from the window. When Saul’s agents came up, she pretended that David was ill and placed a household idol and a net of goat’s hair in his bed, as if her husband were still lying there (vv. 13–16). The midrash states that when Saul learned of this, he was angry with his daughter and demanded of her: “Why did you deceive me and let my enemy escape?” Michal replied: “You are the one who married me to this brigand! David stood over me with a sword to kill me, and said to me: ‘If you don’t help me to escape, I will kill you.’ I was scared. I was afraid of him, and I helped him to escape.” Michal thereby alluded to her father that he was the one who had arranged her marriage to David in return for the military victory over the Philistines, and one should not expect a soldier to change his disposition. For her actions in this episode, Michal was given the appellation of Eglah: like a calf that does not accept a yoke on its neck, Michal did not accept her father’s authority, but stood by her husband (Midrash Tehillim 59:4). The “Woman of Valor” poem (Prov. 31:10–31) praises her for saving David from death and devotes to her the verse (v. 23): “Her husband is prominent in the gates.” (Midrash Eshet Hayil 31:23).

The Rabbis emphasize that even when Michal was given to another, she remained faithful to David. I Sam. 25:44 records that during one of the times that David fled from Saul, the latter gave Michal to Palti[el] son of Laish. According to the Rabbis, Saul did so upon the evil counsel of Doeg the Edomite. Doeg told Saul that since David had rebelled against the king, he deserved to die, and indeed, was already considered to be a dead man: his life was free for the taking, as was his wife. Saul accordingly gave his daughter, who was already married, to Palti (Gen. Rabbah 32:1). The Rabbis maintain that although Michal and Paltiel lived together as a married couple, they did not engage in intercourse. He was given the name Paltiel (palat-el) because God (El) attests of him that he was saved (niflat) from sin, and did not touch David’s wife (Lev. Rabbah 23:10). Paltiel placed his sword between them and said: “Whoever engages in this [intercourse] shall be stabbed by this sword.” Paltiel overcame his sexual urge to such an extent that he was regarded as a woman, and not a man, as is learned from the verse (II Sam. 3:16): “Ishah [that could be understood either as “her husband” or “a woman”] walked with her”—he became for her as a woman. The “Woman of Valor” poem alludes to this conduct by Paltiel (Prov. 31:29): “[Many women have done well,] but you surpass them all” (BT Sanhedrin 19b–20a). Saul, in striking contrast, made light of the sexual prohibitions, and gave a married woman to another; accordingly, he was punished by the loss of his kingship (Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder Eliyahu Rabbah, chap. 29).

Royal Protocol in the Midrash

Michal, the daughter of royalty, who was accustomed to all the details of protocol at the royal court, could not distinguish between the honor of God and that of mere flesh and blood. II Sam. 6:14 tells that when David brought the Ark of the Lord to Jerusalem, he leaped and whirled before the Lord, an act which the Rabbis characterize as debasing himself in honor of God. David, who was wearing golden garments, would clap and strike one hand against the other, leap about, cry out “Keri Ram [Hail, O Exalted One]!”, while the Israelites cheered, blew on shofarot (ram’s horns) and trumpets, and played all manner of musical instruments. When the procession reached Jerusalem, all the women gazed upon David from the rooftops and the windows and saw him dancing carelessly and merrily. When Michal daughter of Saul saw David acting like a commoner, she found this disgraceful. Michal went out to him, but she did not let him enter the house; instead, she gave him a tongue-lashing and began quarreling with him. She told him: “Today the honor of the house of my father Saul has been revealed. Come and see the difference between you and Father’s house. All the members of my father’s household were modest, and no one would see even a bit of their hand, and not even a bit the size of a thumb of their body, and all were more distinguished than you. But you stand and reveal your clothing as one of the worthless ones!” David answered her: “Did I make merry before a flesh-and-blood king? I made merry before the King of kings, who chose me from among your father and all his house. If your father had been more righteous than I, would God have chosen me and rejected your father’s house? In your father’s house they stood upon their own honor instead of the honor of Heaven. As for me, I do not do so—I disregard my own honor and stand upon the honor of Heaven” (JT Booth erected for residence during the holiday of Sukkot.sukkah 5:4, 55c; Num. Rabbah 4:20; Midrash Samuel 25:6).

Michal’s Punishment

The punishment prescribed for Michal (II Sam. 6:23) was that “to her dying day she had no children,” which the Rabbis interpret: she had no children until her dying day, but on her dying day she bore a son. The midrash speaks of three women who had difficult deliveries and died in childbirth: Rachel, the wife of Phinehas, and Michal daughter of Saul. Michal bleated like a sheep when giving birth and died, and therefore she was called “Eglah” (Gen. Rabbah 82:7). This aggadic tradition was meant to resolve the difficulty raised by the identification of Michal with Eglah. II Sam. 3:5 attests that Eglah had a son named Ithream, while Michal was said not to have a child to her dying day. This difficulty could be circumvented if Michal gave birth to Ithream on her dying day. Another Rabbinic proposal is that from that day on Michal was punished by not bearing any further children, but before that fateful day she already had a son by this name (BT Sanhedrin 21a).

The Purpose of Michal’s Nephews

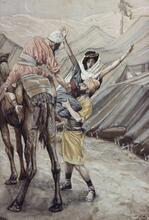

In describing Michal’s maternal traits, the midrash says that she raised her dead sister Merab’s five sons. Merab was married to Adriel the Meholathite and bore five sons. When Merab passed away, Michal raised them as if they were her own offspring, and therefore they are attributed to Michal. This tradition sought to resolve the problem created by the text in II Sam. 21:8, in which Michal is said to have been married to Adriel and to have borne him five sons (Tosefta Sotah [ed. Lieberman] 11:20; JT Kiddushin 4:1, 65b).

The Rabbis further relate of this righteous woman that Michal would put on Phylacteriestefillinn every day, and the sages of the time did not protest, even though there is no The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah requirement for a woman to do so (JT Eruvin 10:1, 26a).