Michal: Bible

Michal’s love for her husband David is evidenced by her efforts to deceive her father, Saul, as he tries to capture David. Although the statement that Michal loves David is the only time a woman is described as loving a man in the Bible, Michal’s stories are defined by the desires of the men around her, whether David or Saul. A notable exception is Michal’s protest against David’s actions after Saul’s death, which she deems vulgar. This moment and the language used to describe Michal show that despite her relationship with David, she is associated with her father’s house, and not with that of King David.

Michal’s Love for David

Michal’s appearances in 1–2 Samuel reflect her confinement as a woman caught in the fierce struggle over the kingship between her father, Saul, and her husband, David. After her introduction in 1 Sam 14:49 as Saul’s younger daughter, she appears next in 18:20, where we read, “Michal loved David.” Saul uses her, as he did her older sister Merab, as a “trap,” in the hope that David will be killed while trying to meet the bride price of one hundred Philistine foreskins. David pays double the bride price, and Michal becomes his wife.

Michal’s love for David helps explain both the risk she takes to save David’s life in 1 Samuel 19 and, later, her angry outburst at him in 2 Samuel 6, when her love has turned to hate. These two scenes, the only ones in which Michal plays an active role, are framed by scenes in which Michal is acted upon: 1 Samuel 19, where she actively takes David’s part against her father Saul, is framed by scenes in which she is acted upon by her father (1 Sam 18:20–29 and 25:44); and Samuel 6, where she takes the part of her father’s house against her husband, David, is framed by scenes in which she is acted upon by her husband (2 Sam 3:13 and 21:8–9).

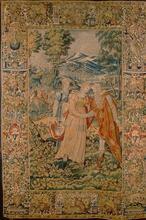

Michal saves David’s life by orchestrating his escape through the window when Saul’s envoys come for him (1 Samuel 19). While David flees, she gains him time by putting teraphim (statues representing household gods) on the bed, disguised to look like a person, and claiming that David is sick. Some commentators take the presence of teraphim as a sign that Michal holds to false religious beliefs, but it should be noted that the teraphim are in David’s house.

Significance

There are parallels between this scene, in which Michal deceives her father, and Rachel’s theft of the family teraphim and deception of her father, Laban (Genesis 31), in which the teraphim are ridiculed. But ridicule is not evident in 1 Samuel 19. Michal lies to her father to conceal her involvement; that she took a great risk is indicated by the parallel to her brother Jonathan, whom Saul tries to kill for abetting David (1 Sam 20:30–33).

The fact that the Bible reports that “Michal loved David” (the only place in the Hebrew Bible where it is stated that a woman loves a man), but not that he loves her, suggests he does not. After he flees Saul’s court, David has two secret meetings with Jonathan, but none with Michal. He does not attempt to provide for her or take her with him, though he arranges for his parents’ safety in Moab and has other wives with him in the wilderness and in the land of the Philistines.

Second Marriage and Family

Saul gives Michal to another man (1 Sam 25:44) in an apparent move to block David from claiming the kingship through her. After Saul’s death, when it is politically expedient, David demands the return of his wife in his negotiations over the kingship (1 Samuel 3). Michal’s husband Paltiel is grief-stricken, but of Michal’s feelings we hear nothing until 2 Samuel 6, where she watches David dancing before the ark and “despise[s] him in her heart” (v. 16). Her rebuke, accusing him of sexual vulgarity, gives vent to her anger over his treatment of her (it also isolates her from David and from the servant women she speaks of as witnessing his cavorting).

Their quarrel raises another important issue by repeatedly referring to the kingship: the rejection of the house of Saul in favor of the house of David. Michal is identified as “Saul’s daughter,” for she speaks as the representative of her father’s house, and, by doing so, forfeits her role in the house of King David. David’s rude reply is his only speech addressed to her in the narrative. Michal’s childlessness is not accounted for (did David confine her, as he shut away other wives [2 Sam 20:3]?) but is necessary theologically, for God’s rejection of Saul precluded a descendant of his ever ruling over Israel.

The statement that Michal had no children (2 Sam 6:23) does not square with the Hebrew text of 2 Sam 21:8–9, where David hands over “the five sons of Michal, Saul’s daughter” to the Gibeonites for execution. Some manuscripts therefore read “Merab” in place of “Michal,” for Merab was the wife of Adriel.

Adelman, Rachel. "Michal: The King’s Daughter or the King’s Wife.” In The Female Ruse: Women's Deception and Divine Sanction in the Hebrew Bible, 137-150. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2015.

Alter, Robert. The Art of Biblical Narrative, 118-123. Basic Books, 2011.

ben Ayun, Chaya. “Between Michal and Rachel—Reflection of Misery.” In Beit Mikra: Journal for the Study of the Bible and its World 48, 289-301. 2003. (Hebrew)

Clines, David J. A., and Tamara C. Eskenazi, eds. Telling Queen Michal’s Story: An Experiment in Comparative Interpretation. Sheffield, England: 1991.

Edelman, Diana Vikander. King Saul in the Historiography of Judah. Sheffield, England: 1991.

Exum, J. Cheryl. Fragmented Women; Feminist (Sub)versions of Biblical Narratives. Valley Forge, PA: 1993.

Exum, J. Cheryl. Tragedy and Biblical Narrative: Arrows of the Almighty. Cambridge: 1992.

Kalmanofsky, Amy. "Michal and Merab." In Dangerous Sisters of the Hebrew Bible, 37-52. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Press, 2014.

Klein, Lillian R. “Michal, the Barren Wife.” In A Feminist Companion to Samuel and Kings, second series, edited by Athalya Brenner, 37-46. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2000.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Seeman, Don. "The Watcher at the Window: Cultural Poetics of a Biblical Motif." Prooftexts 24, no. 1 (2004): 1-50.