Jephthah's Daughter: Midrash and Aggadah

Jephthah’s daughter is portrayed in midrash as a wise and practical woman, well-versed in halakhah and the Torah. In contrast, her father is depicted as haughty and ignorant, making an inappropriate and reckless vow after a military victory. Despite her shrewd arguments, her father nevertheless goes through with his vow to offer her to God and slays her. The rabbis also place the blame for her murder on the High Priest Phinehas for not preventing Jephthah from going through with his vow. According to one aggadah, every year since, in the month of Tevet, on the day on which Jephthah fulfilled his vow, water would turn to blood, and the daughters of Israel would weep for four days over Jephthah’s daughter.

The Rabbis severely criticize Jephthah’s vow and conduct that resulted in the senseless death of his daughter. Jephthah is portrayed as a haughty individual, who flaunts his position as commander of all the military chieftains, when in actuality he was an ignoramus, unlettered in the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah; they compare him to a “sycamore shoot” that is easily broken (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Behukotai 7).

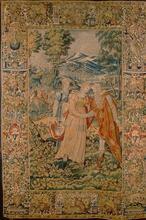

Jephthah’s Vow

In order to win the war against the Ammonites, Jephthah takes a vow that the Rabbis characterize as “unfitting”: “Then whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me on my safe return from the Ammonites shall be the Lord’s and shall be offered by me as a burnt offering” (Jud. 11:31). The Holy One, blessed be He, is angry with Jephthah and tells him: “If a camel, or an ass, or a dog had come out, would you offer it to Me as a burnt offering?” Jephthah’s vow reflects impulsive and ostentatious behavior, without any thought and without taking into account possible consequences. The Holy One, blessed be He, also responded to Jephthah in an “unfitting” manner, and arranged for his only daughter to greet him on his victorious return from battle (Gen. Rabbah 60:3).

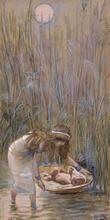

Jephthah’s daughter, on the other hand, is presented as wise and practical. She seeks to find various ways by which to nullify the vow. She tells her father that the Torah commands man to bring offerings of cattle, from the herd or from the flock (Lev. 1:2) rather than human sacrifices. Her father replies that his vow was couched in general wording, “whatever comes out of the door of my house.” His daughter’s response to this argument is that the Patriarch Jacob also made a general vow: “and of all that You give me, I will set aside a tithe for You” (Gen. 28:22), and although twelve sons were later born to him, he did not sacrifice a single one of his offspring. But this argument also fails to convince Jephthah. The daughter is therefore presented—in contrast to her father—as conversant in the laws of the Torah and the stories of the Bible. She argues with her father like a sharp-witted Torah scholar who employs logical reasoning. Unfortunately, none of her arguments succeeds in deterring her father from fulfilling his vow. The A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash asserts that if Jephthah had read the laws of vows in the Torah, he would not have lost his daughter (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Behukotai 7). When the daughter realized that her father would not listen to her arguments, she asked him to go to the Sanhedrin since perhaps they would find a pretext for releasing him from his vow; but the Holy One, blessed be He, hid the law from them.

Collective Responsibility

The Rabbis are also critical of the members of that entire generation, on account of whose arrogance Jephthah’s daughter died. In their opinion, the vow could have been annulled, for a Lit. (from Aramaic teni) "to hand down orally," "study," "teach." A scholar quoted in the Mishnah or of the Mishnaic era, i.e., during the first two centuries of the Common Era. In the chain of tradition, they were followed by the amora'im.Tannaitic The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah states that something not fit to be offered on the altar shall not be so offered and accordingly possesses no sanctity (that it would have as a designated sacrifice) (Lev. Rabbah 37:4; Midrash Statements that are not Scripturally dependent and that pertain to ethics, traditions and actions of the Rabbis; the non-legal (non-halakhic) material of the Talmud.Aggadah, ed. Buber, Lev. 27). Moreover, Phinehas the High Priest lived in that generation and he could have annulled the vow. Phinehas, however, said: “I am a High Priest, the son of a High Priest; shall I debase myself and go to Jephthah, who is a boor?” Jephthah likewise said: “I am the head of the tribes of Israel, shall I debase myself by going to a commoner?” The midrash comments: “And between those two, the unfortunate girl was lost.” In order to depict what befell the daughter of Jephthah, the Rabbis use a popular proverb: “Between the midwife and the woman in labor, the son of the unfortunate woman was lost” (Gen. Rabbah 60:3). The adage reverses the female and the male characters in the narrative. It portrays Jephthah and Phinehas as sabotaging the task that has been entrusted to them; instead of helping to impart life, they take it. Jephthah’s daughter is presented as an infant that has yet to realize itself in the world, and dies through no fault of its own.

Both Phinehas and Jephthah are liable for the death of the latter’s daughter. The High Priest was punished by losing his ruah ha-kodesh (the spirit of divine inspiration), while Jephthah’s penalty consists of the shedding of his limbs, which are buried in numerous places, as is learned from Jud. 12:7: “Then Jephthah the Gileadite died and he was buried in the towns of Gilead.” One limb would slough away and be buried in one location, and then another would fall off somewhere else and be buried there (Gen. Rabbah 60:3).

When Jephthah could find no reason to annul his vow, he slaughtered his daughter before the Holy One, blessed be He, an act that the Lord found loathsome. A heavenly voice cried out at this injustice, and exclaimed: “‘Did I ask that lives be offered before Me?’ As it is said in Jer. 19:5 [in the context of Baal worship]: ‘which I never commanded, never decreed, and which never came to My Mind’” (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Behukotai 7).

Every year since, in the month of Tevet, on the day on which Jephthah fulfilled his vow, water would turn to blood, and the daughters of Israel would weep for four days over Jephthah’s daughter (an ancient aggadah preserved in the Addenda to Mahzor Vitry, p. 14).