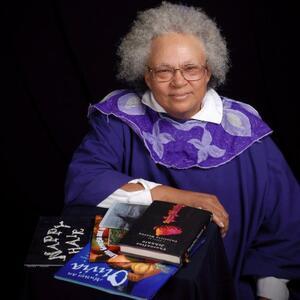

Carolivia Herron

Carolivia Herron is a retired professor, children’s book author, novelist, and librettist. Her work traces classical epic traditions throughout contemporary African American literature and locates convergences and points of contact between Blackness and Jewishness. Her writing is characterized by formal innovation and experimentation and she tells deeply autobiographical narratives that stretch back centuries. Much of her work traces patterns of shared trauma and convergence between Blackness and Jewishness, from the late fifteenth-century Jewish expulsions from Spain and Portugal, to the Atlantic slave trade, to the Holocaust and contemporary racism and antisemitism.

“You must define beauty for Black people!....Our lips are thick, our noses broad, our hair is nappy! We are Black and we are beautiful!” That’s how the fictionalized version of Kwame Ture in Spike Lee’s 2018 film, BlacKkKlansman uses the word “nappy.” The term is undeniably applied in a positive sense, but, importantly, Ture (the historic speech from 1966 uses the same word), employs “nappy” in an “in-group” setting where he talks to a Black audience. Caroliva Herron’s most famous book, Nappy Hair (1997), also used the term in a positive way, but a huge brouhaha erupted when a white teacher in Brooklyn in 1998 taught the colorful children’s picture book to mostly Black and Latino third graders.

Biography

Carolivia Herron was born on July 22, 1947, to Oscar Smith Herron and Georgia Carol Johnson, and grew up in Washington, D.C. She earned a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of Pennsylvania in 1985 and taught at Harvard, Mt. Holyoke, California State University, Chico, and William and Mary. She has published many other books, but Nappy Hair remains the best known. Now retired from her academic career, Herron works with Epicentering the National Mall Coalition in Washington, D.C.

Raised in the Christian faith but with Jewish ancestry and having been interested in the Hebrew Bible, Jews, and Jewishness ever since she was a child, Herron converted to Judaism and held her Bat Mitzvah at the Harvard Hillel in 1996. Much of her work traces patterns of shared trauma and convergence between Blackness and Jewishness, from the late fifteenth-century Jewish expulsions from Spain and Portugal, to the Atlantic slave trade, to the Holocaust and contemporary racism and antisemitism.

In 2011, Be’chol Lashon, an organization devoted to raising awareness about the ethnic, racial, and cultural diversity of the Jewish people, granted Herron a lifetime achievement award for her dedication to children’s literature that explores the diversity of Jewish life, especially Black Jews. Nappy Hair won the Marion Vannett Ridgeway Honor award and Parenting Magazine’s 1997 Reading Magic Award. In addition to children’s books, novels, and academic articles, Herron also wrote the libretto for an opera entitled Let Freedom Sing: The Story of Marian Anderson (2008), which was performed at the Atlas Performing Arts Center in Washington, D.C.

The Nappy Hair Controversy

Nappy Hair (1997) is a brief, tuneful picture book beautifully illustrated by Joe Capeda that celebrates the unruly nature of the main character Brenda’s hair—it has a life of its own, this fantastic hair, and crunches like snow and was so beloved that “God wanted hisself some nappy hair upon the face of the earth.” Brenda runs away from anyone with a comb or chemical processes to straighten or control her revolutionary hair, and the book overwhelmingly revels in it as a source of pride. But the tremendously positive valence of “nappy hair” in the picture book was lost in translation, if you will, when a Black mother found a photocopy of an image from Nappy Hair in her third grader’s folder. The photocopy appeared to this mother to be akin to racist imagery, and in response the enraged mother asked her daughter’s teacher where she kept her KKK hood. The administration of Brooklyn’s PS 75 was called in and the white teacher, Ruth Sherman, was forced to transfer from her position, despite her own avowed good intentions in sharing with the class a celebratory book by a Black-Jewish author. The New York Times and The Washington Post picked up the story and Nappy Hair became news; Herron’s appearances on the Today Show and Good Morning America and many other media outlets followed. Despite overwhelming support for the book by Black writers and pundits, Nappy Hair was banned in some places. No one can fault the parents for being upset, but it remains ironic that a book celebrating subversive Black hair was at the center of such a storm.

For Herron, Nappy Hair is a children’s book only because of the colorful images Capeda painted on each page. The book is not primarily about hair, but rather about the “techniques of African-American storytelling that are comparable to the storytelling techniques of oral poets from ancient Greece and Rome” (Lively, 77). Herron taped her Uncle Richard’s stories about her hair, and much of the fictional Uncle Mordechai’s speech is rendered verbatim from these hair tales.

In an interview with Janice Tuck Lively, Herron discussed the in-group versus out-group nature of the problem and noted that within her family it was fun and fine to use the word “nappy,” but she conceded that, as the Black mothers had been concerned, in the outside—white—world it might have a different valence. Herron took up this debate in the guise of a response from Brenda herself where she explained that Black editors wanted the story published and that “Carolivia has seen young black girls first look at each other in astonishment, and then stand three inches taller, as the community chants its praise of their nappy hair” (“Nappier,” 191). As Kwame Ture and others had used “nappy” as a point of pride, so did Herron. But the subtleties of the phrasing did not always come through.

The Autobiographical Novels

According to literary scholar Brenna Ryan, Herron was sexually abused as a child and as a result, suffers from multiple personality disorder. Both of these themes are prevalent in Herron’s fiction, starting with her novel of trauma, Thereafter Johnnie (1991), and onto her two interrelated autobiographical books, Asenath and the Origin of Nappy Hair (2014) and Peacesong D.C (2016). These texts, which are very similar to each other, are formally innovative, with narrators switching around and voices alternating. Much of Peacesong is written in the second person, with John Milton narrating some parts. The subtitle explains that it’s a “Jewish Africana Academia Epic Tale of Washington City,” and the narrative moves from a childhood filled with books to graduate school at “Pen Forest” university. A brief note explains that although everything in the book is true, it is classified as fiction because “the stories bend toward the arc of storytelling rather than that of rigid facts.” Another note explains that Peacesong was adapted from Asenath.

Underscoring Ryan’s claim that Herron felt multiple in her personalities, one of Peacesong’s narrators asks “Who are all these people, these echoing voices, who live inside your head? They are always chattering and speaking” (15). Like Brenda in Nappy Hair, the main character, Shirah Shulamit Ojero, has nappy hair and, as was the case for Brenda, God choose her hair and she loves it. “You love to touch the puffiness of your hair. You like it that no one else has hair as puffy as yours” (77).

From a very young age, Shira was interested in Jews and Jewishness and struck up a friendship with a local butcher who disapproves, silently, when she buys pork fat. Reading and re-reading the Hebrew Bible, she finds it miraculous that Hebrews walk out of books and into her life. And the nappy hair is related to these biblical stories and to strength: “Your mother tells you that your nappy hair makes you strong too, like Bear Wolf and Samson” (85).

Some chapters are in the form of a play and others cite Nappy Hair, while some recount long stories of Jewish families and their experiences during the Holocaust, the expulsion from Spain, and other traumas, as Shira begins to interconnect anti-Black racism and antisemitism.

Another autobiographical children’s picture book, Always an Olivia: A Remarkable Family History (2007), tells the story of the multicultural Jewish and Black history of Herron’s family, from the Sephardic expulsions from Spain and Portugal through the slave trade and into the present.

Herron’s Academic Work and Scholarly Articles on Herron’s Fiction

In addition to her novels, Herron wrote several academic articles on Milton, Early African American Poetry, and other topics. These were published in Callaloo, The Columbia History of American Poetry, On Philology, Comparative Literature Studies, and other journals and outlets. She also edited the Selected Works of Angelina Weld Grimke for Oxford in 1991. Like Herron, Phillis Wheatley, the first African-America author of a public book of poetry, was very attached to John Milton. Indeed, as Herron reports in her entry on “Early African American Poetry,” “Wheatley so valued the poetry of Milton that she could not be brought to sell her valuable copy of Paradise Lost, even when she was destitute and dying” (21). Herron explains that this edition had been given to Wheatley by the mayor of London and now resides in the Harvard University library. This attachment to a literary text resonates with the experience of some Holocaust survivors, such as Charlotte Delbo, who traded bread for literature in the worst conditions imaginable.

In a text on “Philology as Subversion,” Herron argues that her time spent in Central Africa observing speech patterns indicates fundamental interconnections between Africans and African-Americans that other researchers have either ignored or denied. Herron finds that, threaded through Wheatley as translator of Ovid and avid reader of classical epic, African-American literature has always already been imbued with a mix of European and African traditions. Herron brings a personal voice to her academic work and asserts that she unites “pleasure with political activism in literary studies.” She goes on to argue that she brings the “haves and have nots of literature face to face” by using literary analysis to trace the deep presence of classical epic in African-American literature—from Wheatley to Wolcott and beyond (“Philology as Subversion).

Most of the academic work on Herron’s fiction focuses on her 1991 novel Thereafter Johnnie, which charts an incestuous relationship between father and daughter through references to classical epics and the Hebrew Bible. It is structured in 24 parts narrated by different characters in order to replicate and amplify Milton’s twelve books of Paradise Lost. In Black Subjects, Arlene Keizer offers a detailed analysis of the physical and psychical cartographies employed by Herron in Thereafter Johnnie in order to argue that, in using the geography of Washington, D.C., to engage with the classical references that structure the novel, Herron breaks with other incest narratives by forging a survivor who is articulate and, indeed, complicit. Keizer finds that the novel is “obsessed with the relationship between sexual coercion and complicity” (130). Black Subjects may offer the most sustained analysis of Herron’s work to date and uses psychoanalytic and other close readings to unpack the novel. Several dissertations have been written in the past decade that include discussion of Herron’s work, so we can anticipate greater scholarly interest in this diverse and formally experimental writer.

Selected Works by Carolivia Herron:

“Nappier Hair: In Brenda’s Own Voice or Setting the Record Straight.” The Lion and the Unicorn, Volume 37, Number 2 (April 2013): 188-194.

Nappy Hair. Illustrated by Joe Cepeda. New York: Dragonfly Books, 1997.

“Early African American Poetry.” The Columbia History of American Poetry., edited by Jay Parini and Brett Millier, 16-32. New York: Columbia University Press; 1993. xxxi, 894.

“Philology as Subversion: The Case of Afro-America.” Comparative Literature Studies, vol. 27, no. 1 (1990): 62–65. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40246730. Accessed 28 Apr. 2020.

Banks, Ingrid. Hair Matters: Beauty, Power, and Black Women’s Consciousness. New York: NYU Press, 2000.

“Black Jewish Hip Hop Video Premiere Kicks Off Be’chol Lashon Media Awards.” https://globaljews.org/articles/bechol-lashon/black-jewish-hip-hop-vide…

Lively, Janice Tuck. “The Roots of Nappy Hair: An Interview with Carolivia Herron.” Obsidian III (Spring/Summer 2001): 76-88.

Keizer, Arlene. Black Subjects: Identity Formation in the Contemporary Narrative of Slavery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018.

Lee, Spike (dir.) BlacKkKlansman. 2018.

“Let Freedom Sing: The Story of Marian Anderson” whartondc.com/article.html?aid=1585

Meacham, Rebecca. “The Entanglements of Teaching Nappy Hair.” Race in the College Classroom: Pedagogy and Politics, edited by Bonnie TuSmith and Maureen T. Reddy, 71-83. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2002.

Ryan, Brenna J. “Carolivia Herron.” Contemporary Jewish-American Novelists: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook, edited by Joel Shatzky and Michael Taub. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997.

Smith, Dinitia. “Furor Over Book Brings Pride and Pain to its Author” New York Times 25 November 1998, B10.