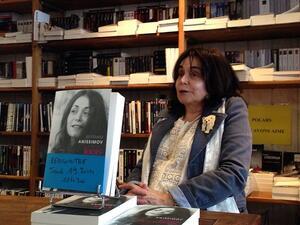

Myriam Anissimov

Myriam Anissimov in 2014.

Courtesy of ActuaLitté/Wikimedia Commons.

In her fiction, Myriam Anissimov addresses primarily the experiences of Jews living in post-World War II France, often drawing on her own experiences as a woman born into a society that is not open to listening to the voice of the Jewish survivor. Autobiographically informed, her novels tend to render descriptions of heroines in pursuit of their own ideas of happiness while being haunted by memories of those who were killed in the concentration camps. As part of her non-fiction work, she has published monumental biographies of celebrated male Jewish artists primarily of European background. This part of her oeuvre, too, is dedicated to the attempt at surveying cultural history in search for modes of Jewish creativity and articulation of Otherness.

Myriam Anissimov is the author of numerous novels dealing with Jewish life in post-war France and of a series of biographies of Jewish writers and artists. Describing herself as “a Yiddish writer of the French language,” she is one of the most prolific voices of her generation writing in France.

Family Background

Anissimov’s autodidact father, Itzik (Yankl) Frydman, was born on April 6, 1914, in Szydtowiec, Poland A tailor by profession, he was also a Yiddish writer. In 1938 he migrated to Lyon, France, where he met and married Bella Frocht (b. Metz, April 11, 1924) in 1942. Anissimov’s parents, who had been members of the French resistance movement, fled to Switzerland in 1942. Anissmov was born on June 15, 1943, in the refugee camp in Sierre, Switzerland, her sister, Denise, was born in 1947.

Myriam Anissimov studied photography in Lyon and then became a singer and an actress, living in Paris from 1966 on. She initially took the name Anissimov because the producer of a record she was making considered the name Frydman as too Jewish. She therefore picked a name at random from the telephone directory and has used it ever since. In 1982 Myriam married the musician and conductor Gerard Wilgowicz (b. 1945).

Career Highlights

Anissimov’s first novel, Comment va Rachel? (How is Rachel?), appeared in 1973, followed by eleven more (often semi-autobiographical) novels, including La Soie et les cendres (Silk and Ashes, 1989), Dans la plus stricte intimité (Family Only, 1992), and Vie et Mort de Samuel Rozowski (Life and Death of Samuel Rozowski, 2007).

In her work as a biographer, too, Anissimov committed herself to postwar Jewish life and letters: Primo Levi, la tragédie d'un optimiste (Primo Levi, Tragedy of an Optimist), which appeared in 1996, was translated into English and won the WIZO Prize in 1997. She also published works on the French-Jewish writer Romain Gary, with whom she had a short a relationship. More recently, she published books on the Russian journalist and writer Vasily Grossman (2012) and on the conductor and pianist Daniel Barenboïm (2019).

Anissimov is the recipient of several awards, among them the prestigious Ordre des Arts et Lettres awarded by the French Ministry of Culture. For her 2018 novel Les Yeux bordés de reconnaissance (“With Dark Circles of Recognition”), she received the Prix Roland-de-Jouvenel de l'Académie Française.

The Plight of the Second Generation

How is Rachel? introduced themes that recur throughout Anissimov’s entire oeuvre. She tries to find a language capable of relating how Jewish women born after the Holocaust deal with their parents’ suffering as persecuted Jews settling in France after the war. She addresses the incongruity between the conditions endured by the inhabitants of the ghettos and the camps, whose personal life was extinguished by mass persecution, and the state of second-generation Jews who encounter humiliation in their private lives as they become the target of latent anti-semitic attitudes. The fear that such a comparison risks trivializing the pain of the persecuted is, paradoxically, eased somewhat when the reader learns at the end of the book that the protagonist is considering suicide by turning on the gas.

Feminist Themes

One of the many strengths of Anissimov’s works lies in their outspoken presentation of the sexual and emotional relationship between the sexes from the point of view of the woman. In this respect, Anissimov’s works are intriguing complements to the American Jewish novel of the 1960s and 1970s. However, her early female protagonists do not subscribe to the sardonic attitudes typical of their male peers in the American Jewish novel of the sixties and seventies. Theirs are often lives of many struggles to which the men they encounter greatly contribute. She portrays the children of the victims as incapable of action and as caught between the guilt of the survivors and the difficulty in finding models of resistance. She often describes the syndrome of “telescoping,” the emotional handing down of traumatic experiences by family members, which has long preoccupied numerous authors. In her later work, Anissimov powerfully reverses the psychological effect described at the beginning of her career and instead follows the imperative of remembering the family lost to the Holocaust.

The heroines of Anissimov’s more recent novels take their lives in their hands and actively face the challenges of their surroundings, examining the discourse of victimization with a historical perspective and sharp intellectual acumen. This attitude can be found most prominently in her Sa Majesté la Mort (Her Majesty, Death), published in 1999 and awarded the Jean Freustié Prize, which is dedicated to the endeavor of re-membering, via writing, a family genealogy endangered by the peril of becoming “unreadable.” Reconstructing the past by searching for photographs and documents, by reading letters, and by listening to the stories of her mother, the author-narrator faces an almost insurmountable challenge of reconstructing a lineage destroyed by the Nazis. Whereas many of Anissimov’s previous works had been based largely on autobiographical materials, Her Majesty, Death does not pretend to be anything other than a memoir. The first-person narrator of the book finds herself confronted at the outset with a genealogical hiatus that only her writing and the research informing her writing can bridge. The book’s initial step is naming in the most concrete manner possible what happened in the past. Anissimov sets a stage for the narrative by pointing out from the very beginning that this stage, once populated, is now hauntingly vacant.

There is no doubt that among today’s Jewish writers in France Myriam Anissimov has a singular voice as a Jewish women writer who addresses the political as well as to the quotidian experience of European Jews after the Shoah.

Selected Works by Myriam Anissimov

Comment va Rachel? Paris: Denoel, 1973.

Le bal des puces. Paris: Julliard, 1985.

La soie et les cendres. Paris, Gallimard, 1989.

Dans la plus stricte intimité. Paris: L’Olivier, 1992.

“Écrivain yiddish de langue française.” Pardès 21 (1995): 237–241.

Primo Levi ou la tragédie d’un optimiste. Paris: Jean-Claude Lattès, 1996, English translation 1999.

Sa Majesté la Mort. Paris: Seuil, 1999.

Vie et mort de Samuel Rozowski: Denoël, 2007.

Romain Gary, l'enchanteur. Paris: Textuel, 2010.

Jours nocturnes. Paris: Seuil, 2014

Daniel Barenboïm - De la musique avant toute chose. Paris: Editions Tallandier, 2019.

Elikan, Marc. “Le sentiment ‘minoritaire’ et identitaire dans la création romanesque de Myriam Anissimov.” Colloquium helveticum 22 (1995): 41–53.

Nolden, Thomas. In Lieu of Memory: Contemporary Jewish Writing in France. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.