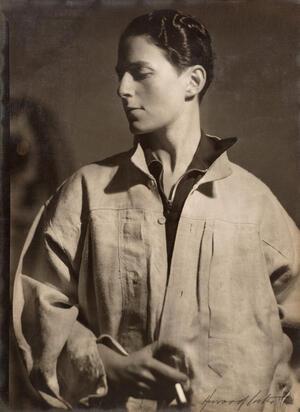

Gluck (b. Hannah Gluckstein)

Mononymous painter Gluck, who signed her artworks “no prefix, no suffix, no quotes,” earned critical acclaim in England during the 1920s and 1930s for her individualist style and eclectic subject matter. (I use she/her pronouns in this piece because that was how Gluck was identified in her lifetime. See Author’s Note below for more details.) Born Hannah Gluckstein of the J. Lyons & Co. catering empire, Gluck rejected the constraints of her conservative upbringing and refused public association with her family or any artistic movement. Instead, she earned recognition for her commitment to representation through several one-woman exhibitions. Gluck also gained notoriety for her gender nonconformity and homosexuality. Medallion (c. 1936), her most famous painting, celebrates Gluck’s unofficial marriage to her then-partner and lifelong love, Nesta Obermer. Later in life, Gluck abandoned painting to advocate for the standardization of oil paints and canvases. She returned to painting for one final exhibition before she passed away in 1978.

Early Life

Gluck, born on August 13, 1895, was the first child of Joseph Gluckstein, the eldest son of one of the wealthiest Jewish families in Britain, and Francesca Halle, an American opera singer. As part of a prominent, conservative, and religious family, Joseph and Francesca Gluckstein never foresaw that their newborn daughter would be known not as the respectable Miss Hannah Gluckstein but rather as the enigmatic and androgynous Gluck.

Joseph co-owned and ran the lucrative J. Lyons & Co. coffee house, catering, and hospitality empire with his brothers. The Gluckstein extended family combined their resources to create “The Fund,” a pseudo-socialist money pool entity administered to benefit all members. The majority of Gluck’s work and lifestyle was financed by The Fund thanks to a 1918 provision written by her father. Despite living off her family’s fortune, Gluck refused any professional association with them, even when their influence could have advanced her artistic career. Gluck especially opposed interference by her well-connected mother, who often ignored Gluck’s wishes and invited her aristocratic friends to her daughter’s shows. Gluck rarely acknowledged her Jewish upbringing, instead aligning herself with Catholic groups and subject matter. Gluck’s religious motivations were unclear outside her resentment towards her Jewish family.

Education and Early Career

Gluck attended St. Paul’s Girls’ School in Hammersmith, London, from 1910 to 1913. Gluck shared her mother’s love and talent for singing, and she oscillated between singing and painting as her primary art form. While at St. Paul’s, Gluck decided to attend art school. The head of St. Paul’s art department vouched for Gluck’s potential as an artist, and her parents eventually allowed their daughter to pursue an artistic education.

In 1913, Gluck began studying at St. John’s Wood Art School, whose teachings she considered entirely useless to her. However, a brief stint in art school provided her with an opportunity for escape. Accompanied by another gender-nonconforming student named Craig, Gluck fled to Lamorna, Cornwall, home of the bohemian Newlyn School of Painters. Gluck and Craig may have been romantically involved at this time, but the specifics of their relationship are unclear. There Gluck flourished under the influence of artists such as Alfred Munnings, Laura and Harold Knight, and Lamorna Birch, who were known for painting realistic pastoral scenes and portraits. In 1915, Gluck painted her earliest known picture, The Artist’s Grandfather, which she supposedly completed in only an hour. The dark background and thick brushstrokes suggest that Gluck had been studying contemporary portraitists such as William Nicholson and John Singer Sargent. The latter was especially influential on Gluck’s work as his portrait of the musician Joseph Joachim reportedly inspired Gluck to choose painting over singing as her profession.

1920s Exhibitions

Gluck and Craig split their time between Cornwall and London leading up to Gluck’s first solo exhibition at London’s Dorien Leigh Galleries in October 1924. At this debut, Gluck exhibited 57 paintings, including Bettina (1917). In this painting, Gluck lightens her hand, depicting the subject with the same satiny smoothness as her fashionable garments. Bettina demonstrates Gluck’s growing fascination with beautiful and remote socialites. Her later portraits of elite women such as Joan Swinstead and Lady Molly Mount Temple would become some of her better-received works.

Between her 1924 and 1926 shows, Gluck’s relationship with Craig ended. In 1923, Gluck briefly entered a professional partnership with queer American artist Romaine Brooks in a portrait exchange. Brooks’ painting of Gluck, entitled Peter (A Young English Girl), is housed in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gluck abandoned her portrait of Brooks after an argument that led to their falling out.

In preparation for her 1926 exhibition, titled Stage and Country and held at the Fine Arts Society of London (FAS), Gluck began a series of theater scenes. Most notable from the series is The Three Nifty Nats (1926), one of the most abstract pieces in her body of work, showing some Cubist influence on the geometricized background and simplified tablecloth. These theater paintings highlight the sumptuous lifestyles that Gluck and her elite circle enjoyed. Gluck complemented these stage pictures with scenes from provincial Cornwall. By contrasting the over-the-top opulence of London society with the isolated tranquility of rural Lamorna, Gluck characterized her life as one of coexisting opposites––where stage and country intersected to form the uncategorizable character Gluck.

Diverse Paintings and the Gluck Frame

After the success of her 1926 exhibition, the Fine Arts Society asked Gluck to exhibit a new collection of paintings. Gluck was heavily inspired by her relationship with Constance Spry, a renowned florist. From 1932 to 1936, Gluck painted flowers in the style of Spry’s arrangements. Using knowledge acquired from her partner, Gluck created numerous floral compositions, the first and most integral to her portfolio being Chromatic (1932). Chromatic became a focal point of her 1932 exhibition, aptly titled Diverse Paintings for the various landscapes, city scenes, portraits, and still lifes that were shown.

For Diverse Paintings, Gluck invented and patented a new frame style consisting of three stepped panels. The “Gluck Frame” was designed to integrate the picture into the environment by painting or wallpapering its surface to match the gallery walls. The three-stepped design of Gluck’s frame added a modernist architectural element to her body of work. A narrower, lighter version of Gluck’s frame was used for an FAS exhibition of Rembrandt and Dürer engravings.

The YouWe Years

At a 1932 dinner party with Spry in Hampshire, Gluck was introduced to socialite Nesta Obermer, an accomplished author and playwright. Although Spry did much to advance Gluck’s career, their relationship dissolved after four years when Gluck declared herself in love with Obermer.

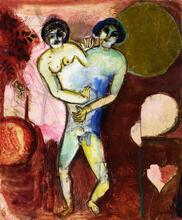

Six months later, Gluck and Obermer “wed” on Christmas day. At some point they exchanged rings, and Gluck marked the date in future diary entries as her YouWe anniversary. To commemorate their union, Gluck painted a double portrait called Medallion (c. 1936, attributed variously to 1936 or 1937), which would become her greatest legacy. Sometimes called the “YouWe” portrait, Gluck and Obermer are shown in profile against a steely gray sky. Gluck falls into shadow as Obermer emerges from behind, bathed in light and looking to an unknown point in the distance. Juxtaposing her stern masculinity with Obermer’s vibrant femininity, Gluck characterizes her lesbian relationship as a heterosexual marriage, with Gluck taking the role of husband and Obermer her wife. This overwhelming desire to situate their marriage in the heterosexual canon is best summarized by Gluck in a letter to Obermer: “Darling Heart, we are not an ‘affair’ are we– We are husband and wife.” In this way, Medallion characterizes Gluck’s concept of lesbian love in conventional terms, effectively justifying her homosexual relationship as an extension of the existing heterosexual norm.

Gluck’s romantic relationship with Obermer lasted from 1936 to 1944. Despite separating, Gluck and Obermer remained lifelong friends, and Gluck considered her to be the great love of her life. Medallion’s legacy outlasted their romantic relationship, eventually becoming one of the better-documented images of sapphic love from the early twentieth century (see Gender Identity & Sexuality).

The Paint War and 1973 Exhibition

After separating from Obermer, Gluck moved in with Edith Shackleton Heald, with whom she lived until Heald’s death in 1976. Heald, an accomplished journalist, took Gluck in after the wartime recession and conflicts with The Fund forced Gluck to sell her private estate. Around this time, Gluck began collaborating with Catholic organizations in retaliation against her devout Jewish family.

During World War II, Gluck completed a handful of paintings depicting life on the home front, but her artistic output was dramatically reduced by the onset of what would be known as Gluck’s paint war. From 1953 to 1967, Gluck produced virtually no new artwork, as the quality of artist’s materials, she argued, had deteriorated so greatly that she could no longer produce work to her standards. More likely, however, Gluck was projecting dissatisfaction with her personal life onto her professional career following her split with Obermer, her mother’s death, and domestic problems between her and Heald.

Gluck appealed to England’s National Arts Council in 1951, demanding that the organization force the paint industry to guarantee certain standards for materials. Over the next decade, Gluck worked closely with both legislators and manufacturers until the British Standards Institution finally published a standard for naming and defining paints.

Although her paint war affected positive change in the art community, Gluck wasted years of creative potential by lobbying rather than painting. Gluck held the last exhibition of her lifetime at the FAS in 1973. The exhibition consisted of 52 paintings, some old and some new, including the few completed works from the paint war years. The exhibition was well-received by critics and the art community alike, introducing a new generation to her work. In a review for Financial Times, art critic Marina Vaizey wrote, “Based on observation of objective reality, linked to inner feeling, Gluck’s work combines the highest professional skill and an indelible emotional quality that makes her work outstanding” (qtd. by Souhami).

Gluck passed away from a heart attack on January 10, 1978, at the age of 82.

Gender Identity and Sexuality

Gluck’s gender expression and sexuality were a source of conflict within her conservative family. Gluck’s father derided the masculine “outré clobber” she wore at all times, and her mother often bemoaned the “kink in the brain” that caused her daughter to act so unconventionally. Still, Gluck’s parents were far more accepting of her queerness than the rest of her extended family. In their eyes, Mr. and Mrs. Gluckstein were enabling their daughter’s outrageous behavior, leading them to unsuccessfully protest against Joseph’s decision to protect Gluck as a beneficiary of The Fund.

Gluck’s overt and subversive queerness inspired artists and thinkers beyond her lifetime. In 1969, Gluck’s cousin Yvonne Mitchell published The Family, a semi-fictionalized play depicting the Salmon and Gluckstein families. Gluck inspired the character Frances, who scandalizes the family by dressing androgynously and adopting the name Frank. In 1982, the women’s publishing house Virago reprinted the seminal lesbian romance novel The Well of Loneliness (1928) by Radcliffe Hall with Medallion as its cover image. Like Gluck, Hall’s protagonist chooses a new name (Stephen) and wears masculine clothing. Virago’s reprint helped introduce Medallion to a wider audience and cemented the double portrait as Gluck’s most influential and well-known artwork. Another retrospective of Gluck’s work was held at the FAS in 2017, accompanied by an exhibition of contemporary women artists who were each given a copy of Gluck’s biography for inspiration.

Gluck has a long history within the lesbian community, but recent movements to acknowledge gender diversity have introduced her to new discourse within the LGBTQ+ community. Gluck expressed gender nonconformity in ways that we now often associate with transgender and nonbinary identities: she chose a new name for herself, cultivated a wardrobe full of masculine clothing, and described herself as the “husband” in her relationships with women. For these reasons, some trans and nonbinary individuals have adopted Gluck as one of their own.

Although these arguments are compelling and socially important, there is no satisfying answer to the question of Gluck’s gender identity. Like in many other aspects of Gluck’s life, Gluck’s gender identity exists in an undefined middle ground. Interpretations of Gluck’s gender identity as cisgender, transgender, or nonbinary are all plausible, adding to the enigma that is Gluck. Nonetheless, the conversation between these different narratives and perspectives makes Gluck a uniquely complex character in LGBTQ+ history.

Author’s Note: Some authors choose to use they/them pronouns when referring to Gluck. I recognize the value of this practice, especially for members of the LGBTQ+ community. As a historian, however, I am uncomfortable imposing contemporary gender concepts on Gluck’s life. Part of being a good historian is meeting your subjects where they are, and there is no way for me to surmise how Gluck would feel about being labeled transgender or nonbinary. Gender identity is immensely personal and nuanced, and I feel I would be doing Gluck a disservice by presuming the answer to such a question. To avoid making any speculative claims, I refer to Gluck using she/her pronouns in this article, as this is how she was referred to during her lifetime. Surviving documents in Gluck’s own voice use first person pronouns only.

Doan, Laura. “Passing Fashions: Reading Female Masculinities in the 1920s.” Feminist Studies 24, no. 3 (1998): 663–700. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178585.

Haye, Amy de la, and Martin Pel. Gluck: Art and Identity. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Lampela, Laurel. “Daring to Be Different: A Look at Three Lesbian Artists.” Art Education 54, no. 2 (2001): 45–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/3193946.

Souhami, Diana. Gluck 1895-1978: Her Biography. London: Pandora, 1989.

Wade, Francesca. “Gluck and Modern British Women.” Studio International: Visual Arts, Design and Architecture, February 24, 2017. https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/gluck-modern-british-women-review-fine-art-society-london.