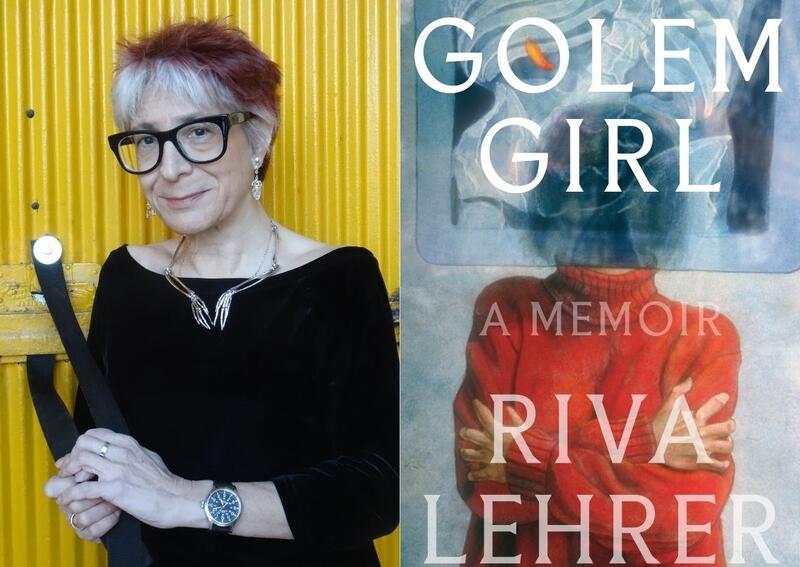

Interview with Riva Lehrer, Artist and Author of "Golem Girl"

This piece is part of a series to mark Jewish Disability Awareness and Inclusion Month. Be sure to check out the other piece, about parenting a child with a disability.

The artist and writer Riva Lehrer was born with spina bifida, a condition in which the spinal column doesn’t close completely during pregnancy. Spina bifida can range from mild to severe, and can result in scoliosis, weakness or paralysis of the legs, loss of sensation, and sexual dysfunction, among other symptoms. JWA spoke with Riva about her recent memoir, Golem Girl, and the way her disabled, queer, and Jewish identities intersect.

JWA: To start at the most basic level, spina bifida is not one thing—it affects people in different ways. Can you explain the ways that it affected you as a child and then later in life?

RL: Disabled kids are often treated like cute little animals. Like they're kind of sad and they're kind of cute and they're kind of vulnerable. And some people are very protective towards them, and the judgments are different. Like people are curious and sometimes spooked. I mean like the Jerry Lewis telethon, you know, was built around kids [with disabilities].

As you get older, the judgments get really different. And once you hit, you know, sexual maturity, that's when the judging really comes down because our societies are built around partnering and reproduction. And our societies in general are built around the idea that disabled people should not reproduce—that, you know, a disabled body is mistake and a problem and drain on society.

As you get older, you acquire more disabilities. My disability is getting kind of conflated with being an old lady. You know, like I can tell on the street that people are very differently protective towards me sometimes, like, “Oh, don't fall over. Be careful.” And I think that I'm being read both as an old lady and as a Crip*. And so there's a compounding.

JWA: The figure of the Golem [an inanimate being that comes to life, seen in Jewish folklore] features prominently in your book, including in the title. Can you say a little bit about the concept of the Golem, and how you relate to it?

RL: Well, I didn't know about the story of the Golem until I was, I think, a teenager. So earlier it would have been Frankenstein that I felt some alliance too. But I think the Golem made more sense to me than Frankenstein because that body is, is built from scratch, by humans. It was closer to be able to see myself [as a Golem] than someone assembled from dead parts. That part didn't quite work for me.

But also, there were expectations for the Golem that were very specific—you know, it had to behave a certain way, and when it stopped behaving that way, it was destroyed. Plus, you know, the doctor and the rabbi both share this kind of mystical superpower sense. And that's certainly how I was raised to regard doctors.

JWA: One thing I really wanted to get your take on, because of the whole notion in disability rights of inclusion and inclusivity, and because this is Jewish Disability Awareness and Inclusion Month…Something that really struck me in your book is the description of your experience at the Condon School [for children with disabilities], which you attended from kindergarten through eighth grade.

You write about it in positive terms, as a positive experience. Because your peers also had disabilities, it was the one place you could…I think you said, “not feel like freaks.” And just the freedom of that, you know, really struck me. It made me wonder, since inclusion is such a buzzword and something activists care about…I was curious about your notion of inclusion.

RL: I'm never going to argue against inclusion, but I think that we are…You know, 20 to 25% of American population is disabled. 20 to 25%. We are the biggest minority in the country and probably in the world. And yet… it is still so hard, it seems, for people to identify as disabled. We have all this language that dances around it—you know, “differently abled” or PWD (person with disability) language.

And I get it, I get it. A lot of people need that. But what all of those do is infer that to say straight up that I am disabled is shameful and a demotion in the hierarchy of humanity. And so we fight for inclusion because we want to be like everybody else, we want to be mainstream, we don't want to be different, etc. What we don't fight for are spaces for just ourselves—you know, social spaces, professional spaces. To some extent we're fighting for academic spaces, in terms of disability studies and critical disability studies.

I can't go anywhere and just hang out with other disabled people anywhere. Before the pandemic, at least Access Living [a New York City-based program] was having regular social events, and that was great. But they were still, you know, up in a conference room, so it wasn't like kicking it back at a bar ,which would have been great or, you know, some place that we could dance the way that we dance. There's nothing, there's nothing.

And so when I hear about inclusivity and mainstreaming and stuff, I just kind of shrug. To me, it's worse than, though it parallels, the disappearance of the “dyke bar,” the lesbian bar.

JWA: Another thing I wanted to ask you about, because you write so eloquently about it, is the way that having spina bifida affected how you and others viewed your gender and your sexuality. You have this line that really jumped out at me: “Spina bifida forced me to perform being female rather than be female.” I wondered if you could say a little bit more about that.

RL: Well, as I say in the book, as I hit puberty, I saw that the girls around me who were not disabled were being enculturated to imagine a traditional female role—you know, wife, mother—and that I was never asked about if I wanted kids or who I had a crush on or did I ever imagine my wedding dress or who was I dating. And, you know, it took a while for that penny to drop, and then once I saw it, it was a real blow.

But I mean, you have to remember, I didn't have words for any of this. This was all totally just wordless and internal. Like I couldn't go to somebody and say, “How come I'm not being treated like my cousin, Diane?” So I just carried the feeling. You know, that's why, meeting the community [of disabled people]… what the community did for me was to give me words and the ability to analyze and to take apart what had happened.

But I think that the one positive in all that is that I've been able to invent myself. I do often feel nullgender or agender, very much. I've never had the desire to be male. There are things about being female that I hold on to, that I claim as my own, but if I stopped doing them, no one would care. And it feels like that gave me space to fall in love with men, fall in love with women, fall in love with one person, who was my partner, who was intersex, and not feel like I was violating boundaries. So there was that. And to be able to talk to other people about having the space and the freedom to follow, you know, the strange path, if that's the one that calls to them.

I don't think I would've wanted to be enculturated the way my female peers were. I mean, I'm a hardcore feminist, so why would I want that? But when you're a kid, you want to be like everybody else. And that's what was hard.

JWA: Of course, I'm also interested in your Jewish identity. I'm curious about the ways in which you feel like your Jewishness has intersected with the other parts of your identity.

RL: As I say in the book, I never was sent to cheder [a school for Jewish children that teaches Hebrew and religious knowledge]. I never was bat mitzvahed. Because again, Judaism is about making more Jews, especially post-Holocaust Jews. They're supposed to make as many Jews as they can. And it was assumed I never would. It was just assumed, you know, I would never be partnered, so where would I be having kids?

And so it was—I guess tacitly in front of me, probably explicitly between the adults—that there was no reason to give me a Jewish education. What was I going to do with it? For me, that meant watching all my friends in the neighborhood and my brothers and my cousins…All the kids were in cheder, and you know, they'd come back and make jokes about it and complain about it. And then, one by one, I'd go to this bat mitzvah, that bar mitzvah and I wouldn't know what the hell was going on. I couldn't read Hebrew. I'm standing there with everybody in my family while they're reading from the siddur. And, you know, it felt terrible.

Habonim [a Zionist youth movement] is where I had my Jewish identity, and I thought I was going to make Aliyah. I did start to try and teach myself Hebrew. I got into Bezalel [a prestigious art school in Jerusalem] and my parents forbade me to go. So, you know, I just have continually felt like my religion doesn't really have a use for me.

JWA: How has that evolved in your in your adult life?

RL: I've belonged to various synagogues and study groups. I feel very culturally Jewish. I mean, like my sense of humor, a lot of the people I read, the actors I love. Our culture has fed me tremendously and I am intensely fond of and connected to it. And I do think I’m a Jewish writer.

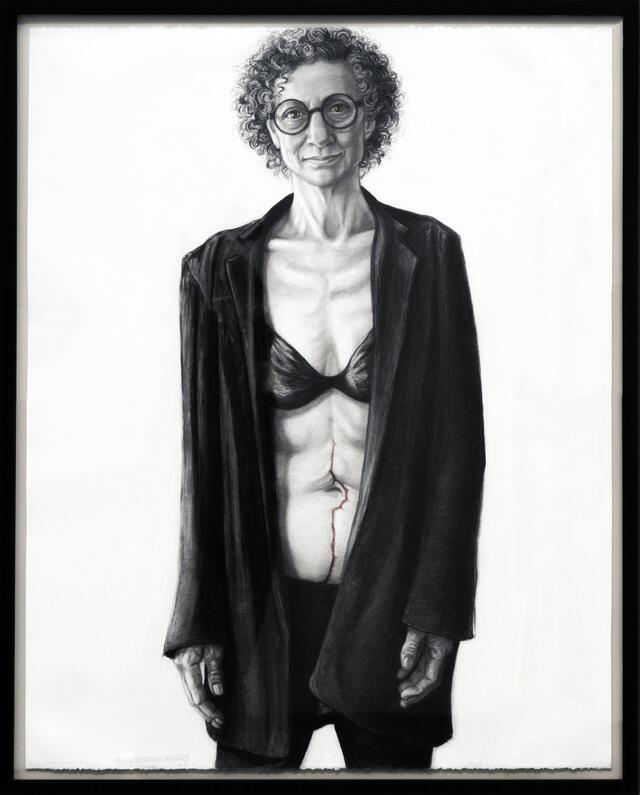

JWA: I wanted to ask you about your portraits and how you came to be drawn specifically to these portraits of people, oftentimes people with disabilities.

RL: I'm not a portrait painter in the traditional sense. What I am is an artist who is trying to understand embodiment through the use of the portrait. So I do portraits in order to understand what it means to live in a body that is socially challenged, that is critiqued, and there's significant pressure always to be other than you are. And that includes people who are queer and trans and, to some extent, people of color, because they end up, sometimes, in situations in which they're considered to be wrong, unacceptable.

I have no interest in just painting pictures of people for their own sake. That's not what I do. I am analyzing what it means to have a body and the implications of having the kind of bodies that I'm portraying. And in that way, my work is political. It's generally not seen as political because most political figuration is built around anger and resistance. And that's not…I could do that, but I'm more interested in the internal self. That's what the portraits are.

JWA: I think there's an interesting way in which, your work is pushing… you know, maybe making people uncomfortable in a way that is important.

RL: I want people to both be uncomfortable and comfortable. Comfortable enough to stand there and approach and not feel yelled at. But I also want them to be confronted with a body that may be problematic for them and have them ask themselves, why is this body problematic?

I am not saying at all that I don't want people to see me as disabled. I am disabled. I want to be seen and understood. I don't like it when people say, “I don't see you as disabled.” I don't like it when people say, “I don't see myself as disabled” or “I'm not like those people” or “I was, but I overcame.”

Being disabled has affected more of my life, the day-to-day reality of my life, than anything else, except maybe being an American with enough money to live inside and not out on the street. Being disabled has formed everything: how I work, how I dress, the rhythm of my days, what car I bought, who I date, what I eat. Everything has become a factor of my disability. And I think that's interesting. I'm capital D disabled and capital J Jewish. I'm certainly capital Q queer and an artist through and through. But my body drives the train.

*“Crip” is slang for “cripple” and is in the process of being reclaimed by disabled people. See here for more information.

Thank you for this insightful conversation. I was so moved by the book, Golem Girl, and the many ways in which our community constructs normalcy around bodies. Riva Lehrer's experiences were so painful, but she has chosen to turn them into a gift for the rest of us in order to help us all look inward and be better. And I also btw really love the art. The portraiture is incredible. Just so many blow-me-away pieces of art. thank you for all this....