Esther: Apocrypha

The Greek Additions to the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Esther were probably written over several centuries and contradict several of the details from the Hebrew text. This version is explicitly religious and contains several verses that do not appear in the Hebrew account. Generally, the Additions are more dramatic and ultimately portray Esther as stereotypically weak and helpless, even though parts of her weakness and femininity ultimately help save her people.

Structure of the Additions

The Greek version of the Hebrew Bible Book of Esther is designated Additions to Esther and pre-serves many details of the Hebrew account. Its portrayal of Esther herself, however, is appreciably different, primarily because of Additions C and D (Add Esth 13:8–14:19; 15:1–16). The Additions to Esther consist of six extended passages (107 verses) that have no counterpart in the Hebrew version. They are numbered as chaps 11–16, designated A–F, and added to the Hebrew text at various places.

Another important “addition” to Greek Esther is the mention of God’s name over fifty times. This has the effect of making the story explicitly religious, in sharp contrast to the Hebrew text, which does not mention God at all. The Additions, which probably were not composed at the same time by the same person, can be dated to the second or first centuries B.C.E. because of their literary style, theology, and anti-gentile spirit.

Esther’s Story in the Additions

After the death of her parents, Esther, daughter of Amminadav (Add Esth 2:7, 15; 9:29; not Avihail, as in the Hebrew Esth 2:15), is raised by her cousin, Mordecai, son of Amminadav’s brother. Like many beautiful virgins throughout the Persian Empire (Add Esth 2:7), Esther is compelled, by the officials conducting the search for a new queen, to go to Susa to compete for the queenship (Add Esth 2:8).

With the other virginal contestants, Esther undergoes an elaborate year-long beauty treatment (Add Esth 2:12), designed to make a candidate for the queenship as desirable as possible. Even though Esther is given preferential treatment by the eunuch in charge, including the promptest service, special cuisine, the finest perfumes, seven choice maids, not to mention his good advice (Add Esth 2:9), she is wretchedly unhappy from the time of her arrival through the next five years of her marriage (Add Esth 2:16, 3:7). Her wretchedness, described in detail in Addition C (Add Esth 14:15–18), is not even hinted at in the Hebrew account.

Addition C corrects all the “flaws” in the Hebrew version of Esther, which was rejected as authoritative by some Jews even as late as the third century C.E. and was one of the last books to enter the Jewish canon, presumably because of its “inexcusable” omissions. In Addition C, Esther prays to “the Lord God of Israel” (Add Esth 14:3), mentions Israel’s “everlasting inheritance” (Add Esth 14:5) and God’s holy altar and house in Jerusalem (Add Esth 14:9), and strictly observes dietary laws (Add Esth 14:17). Moreover, Esther confesses her hatred for every alien, the pomp and ceremony of her office, and her abhorrence at being married to a Gentile (Add Esth 14:15–16). Despite her regal environment, Esther does not partake of non-Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher food or wine dedicated to idols (Add Esth 14:17). Later Jewish commentators credit her with eating only kosher food and faithfully observing the Sabbath (Lit. "scroll." Designation of the five scrolls of the Bible (Ruth, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The Scroll of Esther is read on Purim from a parchment scroll.megillah 13a). The rabbis, however, go even further than the Greek version, claiming that Esther is one of the four most beautiful women in the world (Megillah 15a) and one of only seven female prophets of the Bible (Megillah 14b).

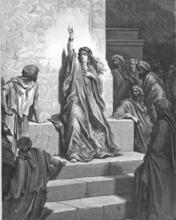

When Esther is finished praying and fasting, she dresses in her finest and, with two maids, approaches the king’s throne unsummoned. What is described by three verses in the Hebrew (Esth 5:1–3) requires sixteen verses in Addition D (Add Esth l5:1–16). Unlike the Hebrew account, here Esther is “frozen with fear” (Add Esth 15:5) and finds the king so terrifying that she falters, turns pale, and collapses on her maid (Add Esth 15:7). Comforted by the king, who sweeps her up in his arms, Esther says to him, “I saw you, my lord, like an angel of God, and my heart was shaken with fear at your glory” (Add Esth 15:13). And then she faints again (Add Esth 15:15).

Portrayal of Esther in the Additions

This high drama in the Greek finds no parallel in the Hebrew, where Esther simply appears and is immediately and favorably received. But the truly great difference in the Greek is that “Then God changed the spirit of the king [from “fierce anger” in 15:7] to gentleness, and in alarm he sprang from his throne and took her in his arms until she came to herself. He comforted her with soothing words” (Add Esth 15:8). This is the high point in the Greek version, in contrast to Hebrew Esther 9, where the establishment of the festival of Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim represents the book’s climax. In the Greek version, God, not Queen Esther, is the “hero.” In other words, just as Queen Vashti was demoted by the king, so Queen Esther is, in effect, demoted by Addition D. In the Greek Additions, Esther is a negative stereotype of female weakness and helplessness, although her fainting spells, like her feminine allure, serve to change the king’s mind and lead to the defeat of the enemy.

Berlin, Adele. The JPS Bible Commentary: Esther. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2001.

Fox, Michael V. “Introduction and Annotations.” In Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture, edited by Louis H. Feldman, James L. Kugel, and Lawrence H. Schiffman, 97-110. Jewish Publication Society, 2013.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Moore, Carey A. “Esther, Additions to.” Anchor Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 2:626–633. New York: 1992.

Moore, Carey A. “Esther, Book of.” Anchor Bible Dictionary, edited by David Noel Freedman, 2:633–643. New York: 1992.

Reinhartz, Adele. “The Greek Book of Esther.” Women’s Bible Commentary, edited by Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, 286–292. Kentucky: 1998.