Creation According to Eve: Beyond Genesis 3

Feminist critics often turn to Genesis 1-3 to discuss the story of the creation of woman, but beyond these chapters there are new insights and stories regarding creation and femininity. Genesis 1-3 may in fact be part of a larger unit of primeval history, which ends only at Genesis 11, where the history of patriarchs and matriarchs commences. These intermediary chapters provide new information on the patriarchal power structure present in the Bible, specifically during creation, and the ways in which it is challenged by Eve. Eve rebels against her role as a subordinate in the processes that hold the female body in such a prominent role.

No feminist critic of the Bible has neglected to discuss the story or stories of the creation of woman; yet, despite significant differences in theoretical approach and focus, their readings generally have been confined to Genesis 1–3. One may well ask why, since the matter of creation and femininity is also addressed beyond Genesis 3. Genesis 1–3 may in fact be construed as part of a larger unit of primeval history which ends only at Genesis 11, where the history of the patriarchs and matriarchs commences. This textual unit consists of a series of narratives and genealogies dealing with creation and crime and punishment—or both.

Christian Interpretation

The tendency to focus on Genesis 1–3 (common not only among feminists) derives in part from the continuing impact of the Christian perception of the Fall as the unequivocal conclusion of Creation. There is, however, no concept of an Original Fall in Genesis. Primeval characters fall time and again in a variety of ways. The first fall is not singled out. Fratricide, sleeping with the Sons of God, incest, and the building of the Tower of Babel are transgressions as exemplary as the eating of the forbidden fruit. Similarly, creation is an ongoing process. The world is wholly destroyed and recreated in the story of the Flood; and on a less cosmic level, this is true of most stories in this unit.

Many feminist critics have sharply critiqued Christian interpretations of the creation stories, but they have done so without calling into question the status of the Fall as a conclusive boundary. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1895), Kate Millett (1969), Mary Daly (1973), Phyllis Trible (1978) and Mieke Bal (1987) provocatively turn the story of man’s Fall through woman (as in Paul’s reading) into the story of woman’s Fall through man, ignoring the fact that Eve does not vanish after Genesis 3, nor does she hesitate to rise and fall again in Genesis 4.

Jewish Feminist Criticism

One of the distinguishing marks of Jewish feminist criticism, here and elsewhere, is the challenge it poses—wittingly and unwittingly—to Christian exegetical presuppositions. Thus, for example, Carol Meyers (1983) sets out to correct the tendency to read the story of the Garden of Eden as one whose central topic is sin and disobedience and calls for a reconsideration of Genesis 2–3 as a “wisdom tale” whose purpose is to address the complexities of human life for both women and men.

Eve’s Naming Speech

In my own reading of Genesis (1992), I go beyond the normative Christian demarcation in an attempt to show that the analysis of Genesis 4 is essential to an understanding of the treatment of femininity in Genesis 1–3. I begin with the opening verses of Genesis 4, where we learn that Adam and Eve, after the banishment, make use of the “knowledge” they acquired back west in the Garden. As a result two sons are born and Genesis 2–3 is linked to the story of Cain and Abel. What is of special interest in this genealogical note is the point in Genesis 4:1 where Eve, who previously was an object of naming, becomes a subject of naming. At the birth of her first son, the primordial mother delivers a fascinating naming speech: kaniti ish et YHWH—rendered by Cassuto as “I have created a man [equally/together] with the Lord”—setting the ground for maternal naming-speeches in the Bible. Naming is not only Adam’s prerogative, as Mary Daly (1973:8) claims, nor is it necessarily a paternal medium. In fact, Eve is no exception; more often than not it is the mother or surrogate mother who names the child.

Eve’s naming speech, however, is rather obscure. Although most commentators would agree that this speech expresses the primordial mother’s joy at the birth of Cain, their translations and interpretations differ significantly. This is far from surprising: every word in this speech poses a problem. The verb kana is polysemic, a feature which has allowed the by-now-discredited translation “to acquire” instead of the less theologically palatable “to create.” The use of the term ish (man) for a newborn boy is odd. But the final part et YHWH (literally, with the Lord) has been by far the most perplexing element. God is always present in procreation—opening wombs, giving seed. What is more, He is often the implied addressee in naming speeches, as is evident in the naming-speeches of Rachel and Leah in Genesis 29–30. But in Genesis 4:1, He is treated scandalously, as a partner rather than as the pivot around whom everything turns.

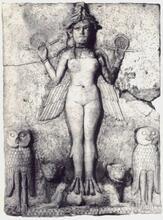

Umberto Cassuto, one of the few to acknowledge the radicality of the verse, suggests that “the first woman in her joy at giving birth to her first son, boasts of her generative power, which approximates in her estimation to the divine creative power. The Lord formed the first man (2:7), and I have formed the second man … I stand together (i.e. equally) with him in the rank of creators” (1961: 201). Eve’s position in the rank of creators allows her to become God’s partner in the work of creation; it allows her to “feel the personal nearness of the Divine presence to herself” (202). Cassuto supports his argument by showing that the verb knh in the sense of “create” is used both in reference to God’s creation of the world—as in the well-known expression koneh shamayim va-arez, the maker of heaven and earth (Genesis 14:22)—and, even more relevantly, in the context of divine parental procreation (Psalms 139:13, Proverbs 8:22). It is precisely by using a verb which in all other cases defines divine (pro)creation that Eve sets the birth of her son on the same footing with the birth of the race. Calling attention to polytheistic elements in the Hebrew Bible, Cassuto goes on to suggest that the same root kny or knw appears in the title of Ashera, the Ugaritic mother goddess: knyt ilm, “the creator/bearer of the gods.”

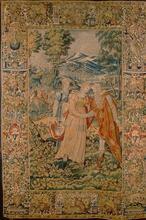

Eve’s naming-speech may be perceived as a trace from an earlier mythological phase in which mother goddesses were very much involved in the process of creation, even if in a secondary position, under the auspices of the supreme male deity. A speech of this sort is undoubtedly a bold provocation in a monotheistic context. If a mother goddess—be it Ashera, Aruru, or Mami—had delivered a similar speech, it could have been construed as “factual” or even as a token of modesty, but when the primordial biblical mother, who is a mere human being, claims to have generative powers which are not unlike God’s she is as far as possible from modesty.

Eve’s hubristic tendencies do not begin here. Already in Genesis 3, the first woman violates the divine decree, opting to become like God. Her naming-speech on the occasion of Cain’s birth is in a sense a continuation of her first rebellion. If in Genesis 3 she ventures to taste the fruit which opens one’s eyes, in Genesis 4 the primordial mother explores the ways in which the “knowledge” she usurped in the Garden of Eden may be realized. Her hubris is transferred to the realm of creativity. By defining herself as a creatress, she now calls into question the preliminary biblical tenet with respect to (pro)creation—God’s position as the one and only creator.

Biblical Power Dynamics

While the Bible is not a feminist manifesto but has a clearly patriarchal thrust, patriarchy is continuously challenged by antithetical trends. That such a challenge in turn does not escape critique may be seen not only in the punishment of Eve in Genesis 3 but also in the change in tone evident in Eve’s second naming-speech: “Adam knew his wife again, and she bore a son and named him Seth, meaning, ‘God has provided me with another offspring in place of Abel’ (4:25). If Eve was the subject of the earlier speech, now God is the subject, the one who provides an offspring. He is restored to his conventional role as the protagonist of procreation. Is Eve more modest and careful at this point as a result of her first encounter with death? Does she take God’s punitive abilities more seriously now that death is no longer an abstract concept?

Eve’s acknowledgement of God’s power, however, does not entail an acceptance of Adam’s rule. The primordial mother still treats procreation as if it were an outcome of a transaction between God and herself alone. Such transactions are a common topic in maternal naming-speeches and serve, in a sense, as a female counterpart to the long conversations men have with God concerning seed and stars.

The ongoing interplay between a dominant patriarchal discourse and various opposing undercurrents is analogous to the tension between the divine plan and the disorderly character of actual historical events. God may be the ultimate authority, yet He is continuously disobeyed. Similarly, man has been officially allotted the position of master over woman, but this does not necessarily imply that she accepts his authority. The official hierarchy God-man-woman is never a stable one in biblical narrative. The capacity to transgress boundaries is one of the essential traits of the biblical character, whether male or female.

In the realm of creation, the “official” hierarchy goes as follows: God is the Creator, Adam is the Son of God, and Eve is a Daughter of Adam (to evoke another primeval story). But the story of creation does not end with the desires of God and Adam. The problem for both male authorities is that Eve rebels against her role as a subordinate of a subordinate in a field in which the female body has a prominent role. Through the naming of her sons, the primordial mother insists upon her own generative powers and attempts to dissociate motherhood from subordination.

Bal, Mieke. Lethal Love: Feminist Literary Interpretations of Biblical Love Stories. Bloomington: 1987.

Brenner, Athalya, ed. A Feminist Companion to the Bible. Sheffield, England: 1993.

Cassuto, Umberto. 1961 (1944). Commentary on Genesis I: From Adam to Noah. Trans. Israel Abrahams. Jerusalem: 1944, 1961.

Daly, Mary. Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation. Boston: 1973.

Meyers, Carol. “Gender Roles and Genesis 3:16 Revisited.” In The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth. Philadelphia: 1983.

Idem. Discovering Eve: Ancient Israelite Women in Context. New York: 1988.

Pardes, Ilana. Countertraditions in the Bible: A Feminist Approach. Cambridge: 1992.

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. The Women’s Bible. Edinburgh: 1985 (1895, 1898).

Trible, Phyllis. God and the Rhetoric of Sexuality. Philadelphia: 1978.