Anarchists, American Jewish Women

The anarchist movement was based on a struggle against the tyranny of capitalism, on social equality and individual liberty, and on the promotion of positive communitarian ideals. Most Jewish women anarchists, while deeply committed to transforming a whole way of life, gave priority to the struggle against oppression by employers, and American Jewish anarchist women participated in immigrant labor organizations in most American cities. They created circles and organizations that represented uniquely anarchist concerns around education and culture/ Jewish women anarchists were at the forefront of radical campaigns that combined forces with gentiles and civil liberties activists to curb abuses of state power. In 1919, the anarchist movement became the target of government persecution, with many members imprisoned and eventually deported, including Emma Goldman and Mollie Steimer.

Early Development

The Jewish anarchist women’s movement in America has largely been associated with the name of Emma Goldman, but her political beliefs were not representative of the majority of members. For Goldman, individual fulfillment and personal liberation were at the heart of the anarchist project, and she had little faith in trade union activism. By contrast, most Jewish women anarchists, while deeply committed to transforming a whole way of life, gave priority to the struggle against oppression by employers, a struggle in which labor organizations played an essential role.

The first Jewish anarchist organization was formally set up as a result of the Haymarket bombing in 1886 and the subsequent trial of the accused anarchists. The inception and growth of the Jewish anarchist movement in the United States were inseparable from the mass immigration of Jews from Eastern Europe starting in 1881. Jewish immigrants from the czarist empire had been schooled in Russian radical politics of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—a period when the revolutionary movement and the anarchist project cooperated against tyrannical oppression by the czar. Jews participated actively in the Russian populist movement (Narodnaya Volya) and in assassination attempts against a succession of government officials and against the czar. Women anarchists like Vera Zasulich, Vera Figner, and Gesia Helfman provided role models for the young generation of Jewish women in the Russian Pale of Settlement who were receptive to secular and political involvement. Some of the women who participated in Jewish radical circles and in anti-czarist agitation at the time of the 1905 revolution subsequently came to the United States.

The development of anarchist ideas in czarist Russia as well as German theoretical thought, as exemplified in Johann Most’s German-language paper Freiheit published in the United States, had an important influence on the Jewish immigrant working class. The anarchist movement gained followers from the fertile ground of the densely populated Jewish immigrant centers, where poverty, sweated labor, and declining wages in the seasonal needle trades were a trademark of immigrant life. The ideology of the movement was based on a struggle against the tyranny of capitalism, on social equality, individual liberty, and the promotion of positive communitarian ideals. These ideals included the free association of individuals and groups without the intervention of the coercive state and social institutions.

Labor Organization

Jewish anarchists, both men and women, participated in immigrant labor organizations in most American cities. Emma Goldman, as well as Rose Pesotta, Marie Ganz, Mollie Steimer, and many rank-and-file women, had all worked and been active in the needle trades. Goldman had participated in the 1890 cloakmakers' strike and in the unemployment demonstrations in 1894. Rose Pesotta, Anna Sosnovsky, Fanny Breslaw, and Clara Rotberg Larsen belonged to an anarchist group within the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, which published between 1923 and 1927 Der Yunyon Arbeter [The union worker] at the height of the rivalry with the communists. Pesotta, who rose to become the only woman on the board of the ILGWU in the 1930s, concentrated her efforts on unionizing Jewish and gentile women workers in the needle trades, as well as workers in other industries. She dedicated her life to promoting more democratic union structures and the advancement of women in the union hierarchy. The goals of women organizers often brought them in conflict with male union leadership, as well as with fellow anarchists who viewed unionism as a mere palliative.

The union provided its members with a community where work struggles were combined with a social life. The anarchists created enclaves in the form of circles and organizations that represented uniquely anarchist concerns around education, culture, and a different way of life. The self-contained groups, however, maintained their roots within the Jewish community. Over twenty such anarchist organizations were branches of the Workmen’s Circle, the Jewish fraternal order. The extensive links with the community muted some of the early expressions of anarchist defiance against religious authority when the early anarchists’ notorious The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur balls were subsequently abandoned.

Community Building

Women anarchists participated actively in these community-building efforts, as well as in another central project, the education of children and adults. Commitment to the abolition of authority extended into this domain too. Schools that emphasized the dignity of the child and the development of the child’s potential in a free and natural setting were the means to prepare members of the future anarchist society. The educational concerns that the anarchists shared with nonanarchist radicals resulted in the flowering of the Modern School movement between 1910 and 1958. The Ferrer Center in New York became in the years prior to World War I a cultural center that attracted progressive educators and the artistic avant-garde. The ideas of progressive education provided the focus and the inspiration for the anarchist colony movement: Stelton (1915) and Mohegan (1923) colonies in New York and the Sunrise (1933) project in Michigan. These mostly Jewish settlements, which were labeled by the outside world as “red” and inhabited by “free lovers,” as in the case of Stelton, were set up around a school and were also experiments in alternative living to promote an anarchist life-style. Stelton ran a cooperative garment workshop and a cooperative food store.

The leading journal of the anarchist movement Di Fraye Arbeter Shtime [The free voice of labor] (1890–1976)—which in its heyday before the Bolshevik Revolution had a circulation of thirty thousand—reflected the labor concerns of its membership. On occasion, the journal also provided a forum for women writers and poets. Anna Margolin, Fradel Shtok, and Yente Serdatzky contributed in its pages to the exploration of women’s concerns, their lives and psychology.

Campaigns

Jewish women anarchists were at the forefront of radical campaigns that combined forces with gentiles and civil liberties activists to curb abuses of state power. Pauline Turkel organized a rally in Madison Square Garden on behalf of Tom Mooney and Warren Billings in 1917. Pesotta campaigned for the release of Mooney from prison in 1934. Other practical causes that they took up included the amnesty of anarchists in Russia in 1911 by the Anarchist Red Cross. Hilda Adel helped to organize the Political Prisoners’ Defense and Relief Committee in 1918 to help protesters who had been arrested for opposing United States intervention in World War I. Rose Pesotta, Emma Goldman, Rose Mirsky, and many others worked tirelessly in the defense of Sacco and Vanzetti in the 1920s.

Most anarchists, including Emma Goldman and Di Fraye Arbeter Shtime, subsequently renounced the violent strand of anarchism, which remained an undercurrent of the mainstream movement until the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901. An assassination attempt on the life of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the perpetrator of the Ludlow massacre in 1914, was the exception. Marie Ganz, a young Jewish immigrant, tried to assassinate him in 1914, but the attempt was foiled. She was one of the militant Jewish anarchists who were inspired by the ideas of the Wobblies (International Workers of the World) and the upsurge of anarcho-syndicalism starting in 1905 and continuing through the period of World War I. In 1914, their activities included organizing the unemployed in New York City and anti-Rockefeller agitation in Tarrytown, New York. Becky Edelsohn, Helen Goldblatt, and Lillian Goldblatt were in the forefront of these confrontational activities.

A similar group set up a separate New York collective whose clandestine publication Der Shturm [The storm] (1917–1918) and subsequently Frayhayt [Freedom] (1918), which agitated against the war, defended the Bolshevik Revolution, and opposed American intervention in Russia, included Mary Abrams, Mollie Steimer, Hilda Adel, Clara Rotberg Larsen, and Sonya Deanin. Some of these women were employed in the garment industry, and Abrams had been in the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. The New York groups joined with supporters from Mother Earth, representing the views of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, to organize militant demonstrations against United States participation in the war, which often culminated in violent confrontations with the police.

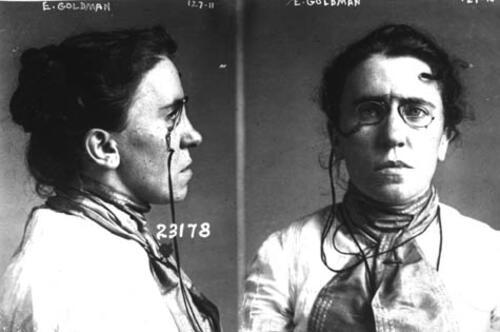

Emma Goldman's deportation portrait, 1919. In post-World War I America, foreigners and their "foreign ideas" were increasingly untolerated. Following her release from prison in 1919, Goldman was immediately re-arrested on the order of J. Edgar Hoover, then director of intelligence for the U.S. Justice Department. Hoover persuaded the courts to deny Goldman's citizenship claims, thus making her liable to deportation under the 1918 Alien Act, which allowed for the expulsion of any alien found to be an anarchist. On December 21, 1919, Goldman and 248 other foreign-born radicals were deported to the Soviet Union.

Courtesy of the Emma Goldman Papers, University of California, Berkeley.

The campaign to oppose the draft conflicted with the forces of Di Fraye Arbeter Shtime, which followed Kropotkin in its support of the war. A more formidable enemy was the U.S. Government. Opposition to the war and direct action advocated by Frayhayt were brutally suppressed through the 1918 Sedition Act. In 1919, the anarchist movement became the target of government persecution with many members being imprisoned and eventually deported, among them Emma Goldman and Mollie Steimer.

The anarchist movement declined as a result of other ideologies competing for the loyalty of the labor movement. For instance, the Bolshevik Revolution drew support from within the ranks of the Jewish immigrant workers in the 1920s, as did the New Deal ideology of the 1930s. However, Jewish anarchist cells and publications continued to exist. Much later, there was a brief upsurge of interest in anarchism among women in the 1960s, when Goldman became an icon again. Her ethics of personal and sexual liberation found many followers in the women’s movement. However, since the 1930s, the appeal of anarchism had given way not only to New Deal ideology, but also to the pro-Zionist orientation of many among American Jewry, which was accompanied by a decline in the use of Yiddish and the waning of the Jewish labor movement.

Avrich, Paul. Anarchist Portraits (1988), and Anarchist Voices. An Oral History of Anarchism in America (1995), and The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States (1980).

Leeder, Elaine J. The Gentle General: Rose Pesotta, Anarchist and Labor Organizer (1993).

Marsh, Margaret S. Anarchist Women, 1870–1920 (1981).

Pratt, Norma Fain. “Culture and Radical Politics: Yiddish Women Writers in America, 1890–1940,” in Women of the Word: Jewish Women and Jewish Writing, edited by Judith Baskin (1994).

Shepherd, Naomi. A Price Below Rubies: Jewish Women as Rebels and Radicals (1993).