American Birth Control Movement

Long before the early twentieth century, Jewish women in western and central Europe and the United States showed commitment to reducing their fertility rates. Jewish women from all backgrounds contributed substantially to the growth of the U.S. birth control movement. Many participated through Jewish organizations like the National Council of Jewish Women, while others worked independently or with secular agencies. In the early twentieth century, prominent Jewish anarchist Emma Goldman featured contraception as a central topic during nationwide speaking tours. Later Jewish women educated the country through organizations like the American Birth Control League (precursor to Planned Parenthood) and books like Our Bodies, Ourselves. Today, Jewish women advocate to make birth control available and affordable, fight to protect the legal right to contraception, and mobilized to pass the Affordable Care Act that guaranteed access to birth control.

Introduction

Jewish women from a range of social and economic backgrounds found common political cause in the American birth control movement and profoundly impacted its successes in the early twentieth century. Radical and socialist Jewish women, in defiance of anti-obscenity laws, distributed information about birth control to working-class women, while middle-class women established clinics and lobbied to overturn the Comstock Laws, which restricted the publication, distribution, and even discussion of material the government deemed obscene. Professional women affiliated with the movement as gynecologists and social workers, and many women enthusiastically sought the financially accessible services of birth control clinics. Later, communal leaders helped start and grow educational efforts like Planned Parenthood and the Our Bodies, Ourselves book project, ultimately lobbying the government to include contraception as required coverage in 2010’s Affordable Care Act. This article charts the grassroots and organizational engagement of Jewish women as the American birth control movement grew from its formative years at the start of the twentieth century to today’s complex and interconnected network of education, activism, and healthcare.

Jewish Women Controlling Fertility

Jewish women in western and central Europe and in the United States attained widespread success reducing their fertility rates well before the start of the American birth control movement. Using available contraceptive methods and performing abortions at rates that far exceeded those of other religiously or ethnically defined groups, central and western European Jews attained rapidly declining fertility rates by the late nineteenth century and soon controlled their fertility more effectively than their non-Jewish peers.

The arrival in the United States of eastern European Jews, whose fertility rates had remained high, generated considerable interest among health care reformers. Although eastern European Jewish families were generally quite large upon arrival in the United States, a trend that continued in the following generation, 1930s studies of fertility rates by ethnic or religious affiliation found that American Jews, including those of the first or second generation, avidly sought birth control services to limit their relatively high fertility rates. Jewish women’s commitment to the birth control cause had dramatic consequences: In 1915, Jews in New York City had the highest number of children per marriage of any immigrant group, but by the early 1930s Jewish fertility rates generally matched the lower national average.

The Reproductive Choice Movement Begins

Jewish female activists were among the first in the United States to bring the need for women’s reproductive control to the public’s attention. Radicals such as Emma Goldman and Rose Pastor Stokes lectured on the importance of contraception and protested against the Comstock Laws, ambiguously defined and arbitrarily applied anti-obscenity legislation. Born in Russia to a traditional Jewish family, Goldman became one of America’s most controversial radical leaders and an early advocate of contraception. In 1900, fourteen years before the founding of Margaret Sanger’s first birth control clinic, Goldman began including the importance of contraception among her lecture topics. Connected with Sanger (1879–1966) through Socialist circles, Goldman defended Sanger’s distribution of birth control literature and began a national lecture tour in 1914 on the importance of legal contraception. Goldman focused on birth control when she spoke at “Yiddish meetings,” “because the women on the East Side need that information most.” Like most of her contemporaneous advocates for contraception, Goldman supported a eugenic argument for birth control: fewer and better children would create a healthier human race. With Ben Reitman (1880–1942), her fellow activist and lover, she published a four-page pamphlet entitled “Why and How the Poor Should not Have Many Children,” which included information about condoms, cervical caps, diaphragms, suppositories, and douches. Goldman faced arrest several times under anti-obscenity laws, and she eventually broke with Sanger for not supporting her anarchist and radical tactics.

Rose Pastor Stokes began her involvement with the birth control cause at a rally to protest Goldman’s arrest, handing out leaflets describing the benefits of contraception. Pastor Stokes, an impoverished eastern European immigrant who began her career in a Cleveland cigar factory, eagerly worked to become a New York journalist, eventually making the front page herself when she married Socialist (and millionaire) J.G. Phelps Stokes. In 1915 Pastor Stokes became the financial secretary of the National Birth Control League, an organization attempting to legalize the distribution of birth control information by repealing anti-obscenity laws. Pastor Stokes disliked the limits of this legislative approach, however, and soon joined a variety of birth control organizations.

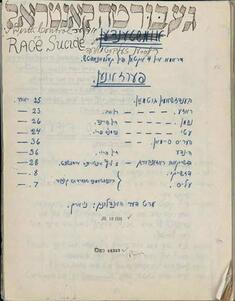

During the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s, the American birth control movement shifted its focus to the rapidly growing number of clinics across the country, and the legal restrictions preventing women from accessing contraception. Immigrant Jewish women and their first-generation children educated themselves about birth control through the Jewish press. Sanger had several of her pamphlets about birth control translated into Yiddish and Polish, but she was not the only source of birth control-related information for Jewish immigrant readers in the United States. Ben-Zion Liber (1875-1958) wrote and published the magazine Undzer gezunt, “Our Health,” which had four thousand subscribers in its first year. “A Jewish monthly for enlightenment in health questions,” it provided news of the birth control movement and of Sanger’s legislative and court battles. He urged his readers to reject “die alte minhagim,” the old ways that might rule out birth control as an option for limiting family size. One issue included “The Truth About Sexuality,” an illustrated pamphlet. A book about sexuality, Dos geshlekhts lebn, went through four editions in 1914, 1918, 1919, and 1927.

The weekly Women’s Page of the Jewish Daily Forward, or Forverts, provided a forum for education and debate about birth control. The Forward had a daily circulation of 200,000 in 1919, making it the leading Yiddish newspaper in the world and “the voice of a vibrant left-wing working-class Yiddish culture.” Advice columns offered guidance to mothers and brides, who often wrote in with anxieties or dilemmas related to sex and family size. The columnists reasoned that limiting family size would improve the “quality of life for mothers” and help them gain the ideal socialist family.

Meanwhile, middle-class Jewish women contributed to the birth control cause through their participation in voluntary organizations, helping women of lesser means gain access to contraceptives, abortion, and other types of reproductive health care.

National Council of Jewish Women

The National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW) pioneered the establishment of birth control clinics, usually referred to as Mother’s Health Bureaus, during the 1920s and 1930s. NCJW’s activities had always centered family-based care, and by emphasizing the woman’s role in her home and with her family, the Council contributed its values and influence to the birth control movement.

In 1932 NCJW’s Brooklyn section opened a new Maternal Health Center. Throughout the 1930s the Brooklyn chapter of NCJW supplied funds and volunteers for the Center, which expanded to include three clinics. By the fall of 1946, the Brooklyn Mothers’ Health Clinic combined its services with Brooklyn’s Planned Parenthood chapter, and in 1947 the clinic handled 3,500 cases. In 1955 the Brooklyn section of NCJW gave full responsibility for the clinic to the newly formed Planned Parenthood Committee of Brooklyn.

NCJW’s New York section opened a Mother’s Health Bureau at its Council House in the Bronx in 1930 or 1931. Early on, the NCJW struggled to keep the busy clinic staffed and stocked, as doctors, nurses, and volunteers handled a deluge of clients. Affiliated with Sanger’s American Birth Control League, the Bronx clinic assisted approximately 500 patients in 1935.

Jewish women’s organizations also established clinics in the Midwest. NCJW’s Detroit section opened a Mother’s Health Clinic in the late 1920s, the first birth control clinic outside of New York and Chicago. Chicago Women’s Aid (CWA) began in 1882 as the Young Ladies Aid Society to assist Russian immigrants and had a mainly Jewish membership throughout its existence. CWA opened a birth control clinic in 1923 and collaborated with Planned Parenthood from 1928 to 1947.

Ultimately, Jewish women served unusually frequently as the public face of birth control clinics across the country, alongside their coreligionists working as activists, professionals, and researchers. As Melissa Klapper explains in Ballots, Babies, and Banners of Peace, “These Jewish women directed clinics, promoted sex hygiene and often marriage counseling in their communities, advocated for relaxation of anti-birth control statutes in their states, wrote books about contraception, worked to overturn restrictive legislation, advised policy makers, and, most importantly, served as the human face of the movement for many thousands of women.”

Activism Outside Jewish Agencies

Not all Jewish women participated in the birth control movement through Jewish organizations like NCJW. Active in a variety of Jewish, feminist, interracial, and Zionist organizations, Gertrude Weil of Goldsboro, North Carolina joined the birth control movement as a lobbyist. She petitioned Congress on behalf of legislative campaigns to remove criminal penalties for importing birth control devices and transporting birth control information through the United States Postal Service. She supported Planned Parenthood financially throughout her life.

Like many of her peers, Weil’s interest in birth control incorporated eugenics-based ideology. During the Depression many members of the middle class apprehensively observed the population increase among working-class immigrants and the poor. Doctors informed about birth control, Weil wrote to Margaret Sanger in 1932, would appreciate “the importance of controlling the reproduction of the unfit.” Between 1935 and 1942, Weil served on the Board of Directors of the North Carolina Maternal Health League, which sought to “do something” about the high birth rate and infant and maternal death rates among families on relief. For middle-class women who supported the birth control movement, advocating for contraception presented a means of allaying their class-based fears while crusading for their own interests as women.

Jewish women’s activism in the American birth control movement also included close association with Margaret Sanger and other national birth control organizations. Two of Sanger’s primary assistants, Anna Lifschiz (1900?–?) and Fania Mindell (1891–1969), immigrated from eastern Europe. Lifschiz worked as Sanger’s secretary between 1916 and the early 1920s. Mindell, a Russian immigrant who trained in the United States to become a social worker, helped Sanger set up the Brownsville clinic in Brooklyn, ran the clinic during its first week of operation, and read birth control literature aloud in Yiddish to the clinic’s many Jewish clients. When police shut down the clinic on obscenity charges a week later, they arrested Mindell, though a judge later reversed her fifty-dollar fine.

Jewish women served as directors and staff at the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau, later called the Margaret Sanger Bureau, which opened in New York City in 1923. A legal loophole allowed doctors to prescribe birth control if it seemed “medically indicated,” or if the patient’s physiological condition would make pregnancy hazardous. Dr. Hannah Meyer Stone, the daughter of eastern European Jewish immigrants, became director of the Bureau in 1927. Stone amended the clinic’s list of medical indications to include the desire for child spacing and psychological factors. Over 5000 women received treatment at the clinic in 1929, including return visits for checkups and supplies, “more than the aggregate of all the rest of the voluntary birth control clinics in the country combined.” Stone kept the clinic open five days a week, with evening sessions for working women and educational sessions that taught hundreds of physicians how to fit diaphragms. Twelve doctors worked part-time for her, in addition to the nurses, social workers, administrators, volunteers, and field workers she required to keep detailed records and follow up on patients. Lena Levine, the daughter of immigrants from Vilna, Lithuania, later directed the clinic for several years, helped Sanger found Planned Parenthood in 1948, and became the medical secretary of the International Planned Parenthood Federation. Levine also coauthored sexual and medical advice books.

Female Jewish doctors also directed birth control clinics throughout the country, including Rachelle Slobodinsky Yarros (1869–1946) in Chicago, Bessie Moses in Baltimore, Sarah Marcus (1894–1985) in Cleveland, and Nadina Rinstein Kavinoky (1888–?) in Los Angeles. For all of these women, working in a birth control clinic provided the professional recognition and responsibility still largely unavailable to them in the male-dominated worlds of academic medicine and hospital politics.

Medical Revolution

Gloria Steinem, who exemplifies the Second Wave of American Feminism, began her career as a journalist writing under a man's name. She went on to co-found Ms., the first feminist periodical with a national readership. An advocacy journalist, she writes passionately about issues of women's empowerment and gender, racial and economic equality.

Courtesy of Sylvia Edwards, Longview Community College

By the 1950s, birth control had developed a more mainstream acceptance in United States health care, but controversy reemerged in 1960 with the approval of Enovid, a highly effective birth control pill for women. For the first time, women could independently control their reproductive choices, an innovation celebrated by feminists but condemned by those supporters of birth control who believed that its use should be restricted to married women. In particular, doctors who prescribed the pill—by 1970, men still represented 94% of the profession—often held strong conservative beliefs about who should be having sex. Jewish feminist luminaries like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan stepped up to advocate for all women’s access to the birth control pill.

Betty Friedan, whose mother was a Jewish newspaper editor who gave up her career to raise three daughters, lost her own job as a successful reporter after the birth of her second child, when her boss would not allow her to take maternity leave. An honors graduate of Smith College, Friedan soon discovered that many of her classmates experienced similar unhappiness about being forced to abandon their careers after becoming mothers. In her landmark 1963 book The Feminine Mystique, in which she challenged the “myth of domestic happiness,” Friedan explained that birth control helped women access the same opportunities as men. “Society had to be restructured,” she explained, “so that women, who happen to be the people who give birth, could make a human, responsible choice whether or not—and when—to have children, and not be barred thereby from participating in society in their own right. This meant the right to birth control and safe abortion,” in tandem with “the right to maternity leave and child-care centers.”

Another Jewish leader of the Second Wave Feminist movement, Gloria Steinem, advocated for access to birth control as a mechanism of freedom and self-determination for all women, married and single. “Women’s bodies will no longer be owned by the state for the production of workers and soldiers,” Steinem said, testifying before Congress in 1970 to advocate for the Equal Rights Amendment. “Birth control and abortion are facts of everyday life. The new family is an egalitarian family.”

Meanwhile, the Jewish mainstream gradually established a consensus in support of access to birth control. In this case, the organizations and their leaders followed the lead of the huge majority of Jewish women who regularly depended on contraception, rather than developing an early opinion or recommendation for the community to follow. Although Jewish leaders remained concerned about the foundational link between contraception and eugenics, they ultimately recognized that American Jews would benefit substantially from the availability of birth control, and the Jewish community capitalized on the image of alignment among religious tradition, communal culture, and modern medical technology.

A New Education: Women Take Charge

Founding Members of the Boston Women's Health Book Collective, 1976. Back (L-R) Ruth Bell, Judy Norsigian, Vilunya ("Wilma") Diskin, Jane Pincus, Middle (L-R) Pamela Berger, Esther Rome, Joan Ditzion, Norma Swenson, Paula Doress, Front (L-R) Wendy Sanford, Nancy Hawley. Courtesy of the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Harvard University.

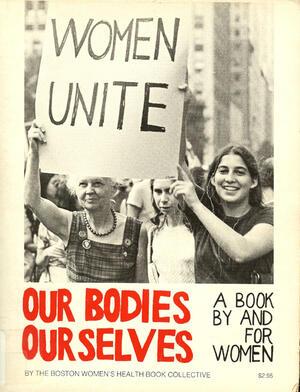

In 1969, a group of Boston women began an ongoing dialogue about the state of women’s health care, exchanging tips on which male doctors to trust and frustration about the dearth of useful resources. “At the time, there wasn’t a single text written by women about women’s health and sexuality. We weren’t encouraged to ask questions, but to depend on the so-called experts,” said Nancy Miriam Hawley, one of several Jewish participants in the initial meetings, along with Esther Rome (an observant Jew), Paula Doress-Worters, Vilunya Diskin, Joan Ditzion, and Jane Pincus. Over the next two years, the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective filled that gap by designing a women’s health course that evolved into a published book: Our Bodies, Ourselves.

Cover of the 1973 edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves.

Courtesy of www.ourbodiesourselves.org

Chapter Seven of the original print edition focused exclusively on birth control. Topics included a detailed account of the process of conception, information about effective birth control methods, lists of methods that “Don’t Work Very Well” and that “Don’t Work at All,” and instructions for preventing pregnancy after intercourse. The last section explains how to end one’s fertility “When You Are All Done,” and the chapter ends with an optimistic note about possible future innovations in male-based contraceptives.

Over the ensuing years, the book repeatedly evolved based on contributions from successive generations of Jewish and non-Jewish women, including Judi Hirshfield-Bartek, contributor to the 1998 edition’s “Medical Practices, Problems, and Procedures” section and one of JWA’s 2001 Women Who Dared honorees. The nine editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves went on to sell 4.5 million copies, and the Collective translated it into more than 25 languages so women around the world could access clear, safe, and accurate information about their health.

Protecting and Preserving Access

As newer contraceptive options with more innovative mechanisms emerged, advocates knew that the messaging around birth control needed to evolve as well to stay relevant. Dr. Ruth Westheimer, the Jewish sex therapist and media personality, regularly taught audiences about the benefits and usage of birth control options, emphasizing their importance in her popular discussions about the joyful aspects of sex and sexuality. She rose to national prominence in the early 1980s, a time when HIV increased the danger of unprotected sex and conservative, Evangelical attitudes gained traction condemning non-procreative sex as improper and shameful. Westheimer’s advice, rooted in Orthodox ideas of sex as a joyous act, helped a new generation build its own relationship with contraception.

Birth control and the right to access it faced regular legal threats as well. Griswold v. Connecticut (1975) established married couples’ right to buy and use contraceptives without government restriction, but the issue arose again several times. In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt case affirmed the right of all people to access reproductive health care and prohibited the government from blocking that right. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the first Jewish female justice, emphasized in her concurrence that safe access to reproductive care was essential. “When a State severely limits access to safe and legal procedures,” she wrote, “women in desperate circumstances may resort to unlicensed rogue practitioners, faute de mieux, at great risk to their health and safety.”

A New Round of Challenges

In March 2010, Congress passed the Affordable Care Act, providing all Americans access to certain fundamental elements of health insurance coverage. One of those elements guaranteed coverage of all FDA-approved contraceptives at no cost to the patient but allowed certain religious organizations to opt out of the guarantee if contraception violated their religious beliefs. Since 2010, that exemption has dramatically expanded to include religiously affiliated schools and hospitals, and even private business where the owner objects to birth control access.

In response, Jewish organizations initiated an ongoing campaign to eliminate the exemptions and provide every patient with full contraception coverage. “Jewish Americans believe in a society where all people have their health care needs met, and that includes reproductive health care,” said Stosh Cotler, then CEO of Bend the Arc. “We will continue to work with our allies in faith communities nationwide to advocate for affordable, comprehensive birth control for all Americans.” Nancy J. Kaufman, then NCJW’s CEO, agreed: “There are differing religious views on the use of contraception, and it should be up to women to decide on whether and when to use contraception based on their own beliefs and needs. By allowing employers with religious or moral objections to deny coverage of birth control to their employees, the beliefs of an employer are once again being held in higher regard than the religious and moral beliefs of the employee.”

The changing landscape of reproductive healthcare has continually led to new innovations in birth control. Simultaneously, each decade has also brought new waves of opposition and different restrictions on contraception’s availability. At every stage, Jewish women have driven the movement forward, actively participating in national and local conversations, and advocating for the right to access safe, effective birth control.

Archival Sources

Chicago Women’s Aid Papers, University of Illinois Library.

Gertrude Weil Papers, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, Raleigh, North Carolina. Margaret Sanger Papers—LC, Reel 9.

National Council of Jewish Women, New York Section and Brooklyn Section, Papers, American Jewish Historical Society.

Printed and Secondary Sources

“A Brief History of Birth Control in the U.S.” Our Bodies, Ourselves. https://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/book-excerpts/health-article/a-brief-history-of-birth-control.

Antler, Joyce. Jewish Radical Feminism. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

“Betty Friedan and the Women’s Movement.” Bill of Rights Institute. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/betty-friedan-and-the-womens-movement.

Boston Women’s Health Collective. Women and Their Bodies. Boston: self-published, 1970.

Chesler, Ellen. Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992.

“Issue Focus: Contraceptive Access.” National Council of Jewish Women. https://www.ncjw.org/act/action-resources/issue-focus-contraceptive-access.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. United Kingdom: Gollancz, 1963.

Gibbs, Nancy. “The Pill at 50: Sex, Freedom and Paradox.” TIME Magazine: April 22, 2010. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1983884,00.html.

Goldman, Emma. Living My Life. New York, Alfred A. Knopf Inc, 1931.

Gordon, Linda. Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right: Birth Control in America. New York: Grossman Publishers, 1976.

Isaias-Day, Sofia. “‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’ in 2022.” Jewish Women’s Archive: March 16, 2022. https://jwa.org/blog/risingvoices/our-bodies-ourselves-2022.

“Jewish Groups Oppose Rollback of Contraception Coverage.” The Times of Israel, via Jewish Telegraphic Agency: October 8, 2017. https://www.timesofisrael.com/jewish-groups-oppose-rollback-of-contraception-coverage.

Klapper, Melissa R. “The Drama of 1916: The American Jewish Community, Birth Control, and Two Yiddish Plays.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era Vol. 12, No. 4 (2013): 502-534.

Klapper, Melissa. Ballots, Babies, and Banners of Peace. New York: New York University Press, 2014.

Koffman, Lori. “Jewish Perspectives on Reproductive Realities.” National Council of Jewish Women: 2018.

“Life Story: Betty Friedan – Women & the American Story.” New York Historical Society. https://wams.nyhistory.org/growth-and-turmoil/cold-war-beginnings/betty-friedan.

Oransky, Ivan. “Dr. Ruth Talks on Sex, Signs Condoms.” The Harvard Crimson: October 29, 1991. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1991/10/29/dr-ruth-talks-on-sex-signs.

“Physician Statistics Summary (1970-1999).” Pinnacle Heath Group. https://www.phg.com/2000/01/physician-statistics-summary.

Rosner, Fred. “Contraception in Jewish Law.” Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought Vol. 12, No. 2 (1971): 90-103.

Sanger, Margaret. An Autobiography. New York City: W. W. Norton, 1938.

Schwartz, Penny. “The Jewish Voices Behind ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves.’” The Jewish Journal: January 29, 2019. https://jewishjournal.org/2019/01/10/the-jewish-voices-behind-our-bodies-ourselves.

Tobin-Schlesinger, Kathleen. “Population and Power: The Religious Debate Over Contraception.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1994.

Wells, Susan. “Our Bodies, Ourselves: Reading the Written Body.” Signs Vol. 22, No. 3 (2008): 697-723.

Westoff, Charles F. and Ryder, Norman B. “United States: Methods of Fertility Control, 1955, 1960, & 1965.” Studies in Family Planning Vol. 1, No. 17 (1967): 1-5.

Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt. 15-274, 579 (U.S. 2016).

“Why Women’s Liberation – Women & the American Story.” New York Historical Society. https://wams.nyhistory.org/growth-and-turmoil/feminism-and-the-backlash/why-womens-liberation.