Rivka Basman Ben-Hayim: Poetry as Spiritual Resistance

Many people question the purpose of art during difficult times. When we’re constantly being bombarded by news of tragedy, both globally and in our own communities, how can paint on a canvas or ink on paper possibly fix anything? It seems pointless. Yet at the same time, as an artist and writer, I ask myself the opposite: how can we stop making art? And if we agree that art is necessary, how can we use art to help create a better world?

To answer, I turn to Rivka Basman Ben-Hayim’s poetry.

Rivka Basman Ben-Hayim grew up in Lithuania and was a teenager when the Nazis invaded her country. She survived two years in the Vilna Ghetto before being sent to the Kaiserwald concentration camp. Kaiserwald was not an extermination camp, but rather a labor camp; Basman Ben-Hayim, along with the other prisoners, was forced to do slave labor.

One of the Nazis’ main tactics during the Holocaust was dehumanization to try to justify the horrific genocide they were executing. Dehumanizing efforts were at the core of concentration camps, where Nazis stripped prisoners of any former identity. In this cruel environment, it could have been easy for Basman Ben-Hayim to give up hope. Yet at the moment when her humanity was threatened the most, Basman Ben-Hayim turned to art. In doing so, she refused to surrender her humanity or hope to the Nazis. Each day she would write poetry, and then in the evenings, she’d recite her poems to the other women to raise morale.

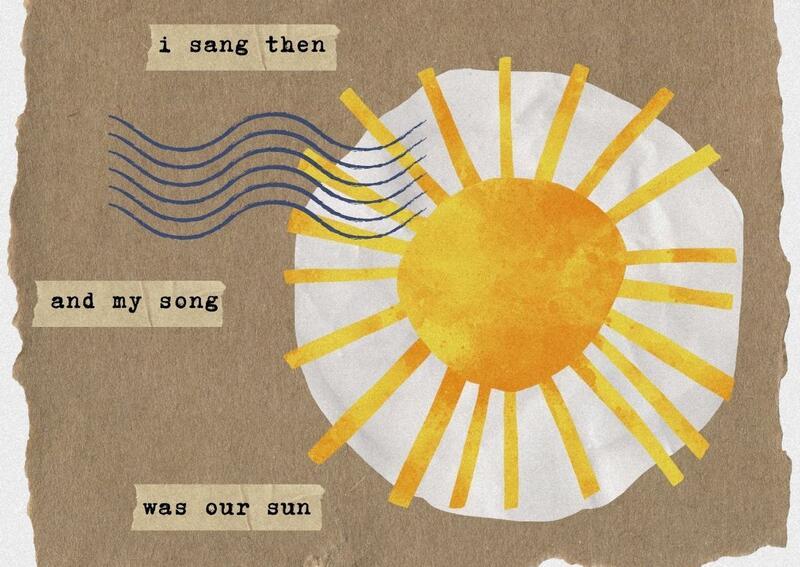

One of my favorite poems of hers is called “Recollection.” In the last three lines, she references her experiences writing and reciting poetry in Kaiserwald; “I sang then/and my song/was our sun.” To me, the image of art as a sun encapsulates the reason we continue making art, despite everything. To put it simply, we can’t live without it. Art is at the backbone of everything humans have ever done because to be human is to create. Sometimes our art is a reflection of the beauty we’ve experienced and so to create is to make the world more beautiful, like the sun illuminating a gorgeous landscape. Other times, our art reflects tragedy. We continue to make it because, just like the sun rising is a constant amidst chaos, creating might just allow us to make it through another night.

Many people have portrayed Jews as passive and almost complicit in their own deaths during the Holocaust. While this is inaccurate for many reasons, the most commonly cited reason is the numerous Jewish armed resistance groups that fought back. However Basman Ben-Hayim’s writing illuminates how Jews fought back in many other ways, too.

When people talk about resistance, most often they’re referring to military action or political activism—protests, boycotts, petitions. But what we so often forget about, and what’s just as important, is spiritual resistance. Basman Ben-Hayim’s poetry is a form of spiritual resistance because it shows her determination to take up space when her existence was being questioned. Her poetry is powerful because it acknowledges the extent of human suffering yet simultaneously refuses to surrender to it. Indeed, even the act of writing poetry is a form of resistance because art is a manifestation of what makes us human.

Looking at the news, it’s easy to get overwhelmed. Compared to increasing antisemitism, abortion bans, and countless other issues in the world, what good am I doing scribbling down poetry in notebooks or covering canvases with paint? But when I start to have those doubts, I think about women reciting poetry in concentration camps, reclaiming their humanity, letting the words be their sun.

No, it’s not enough to end a war, to win back rights, to eliminate hate completely. But it can be enough for now. It can be enough to help someone get through the day, and to keep resisting. As a woman, a queer person, and a Jew, my existence is often debated and my rights denied by the federal government. To continue making art is a declaration. It’s a refusal to remain complicit in my own dehumanization. It says I’m here, I exist, I’m human, and I’m not going anywhere.

This piece was written as part of JWA’s Rising Voices Fellowship.