Rachel Finkelstein's Queer Feminist Holocaust Art

How can art be used to illuminate one’s relationship to the past? The recent works of multimedia artist, political activist, and queer Jewish feminist Rachel Finkelstein offer a unique approach to this question.

Underpinned by themes of women’s identity and sexuality, Finkelstein has been making and exhibiting her art globally since the 1970s. More recently, her work explores her relationship to the Holocaust and her grandmother, whose murder in a mass grave in southern Poland around 1941–42 she has little information about.

Finkelstein obtained a bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts from Central Saint Martin in 1979. She also has two master’s degrees in Art and Fine Art/Photography from the Royal College of Art and California State University and is currently pursuing a third at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Finkelstein has always been something of an outlier, both as an artist and an individual. From flying to Holland from Israel with a one-way ticket as a claustrophobic young adult in 1973, to her arrest at a London demonstration in support of the right to free abortions in 1977, she has railed against convention. The same is true of her artwork. Finkelstein’s art often confronts “taboo” subjects and subverts social norms—particularly pertaining to gender and sexuality. While living in London as a young artist in the 1980s, for example, Finkelstein caused a stir when she exhibited a provocative series of nude portraits of her then-girlfriend, onto which a chastity belt was projected. It comes as no surprise, then, that Finkelstein’s political activism, personal life, and art overlap.

More recently, Finkelstein has turned to art not only as a means of thinking through her relationship to inherited trauma as a third-generation Holocaust survivor, but to four generations of women in her family. This includes her daughter Sacha, herself, her mother, and her grandmother. Born on three continents (Europe, Asia, and America), these women do not share the same native tongue, and three of them never had the chance to meet (Finkelstein and her daughter have never met their grandmothers). And yet, these women are inextricably connected by their womanhood, Jewishness, and a shared historical and biological lineage.

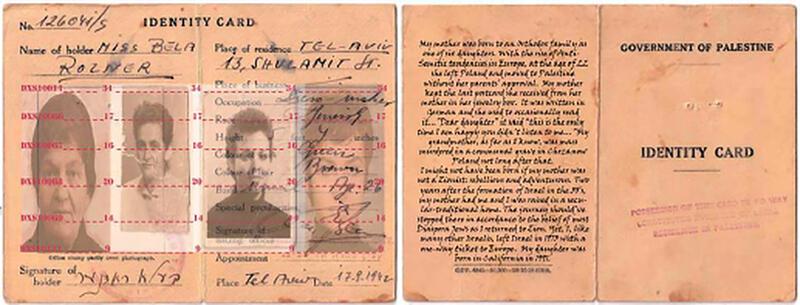

The Herstory (2012) weaves a tapestry of these intertwined generations. It superimposes photographs of each woman onto the identity card issued by the government of Palestine to Finkelstein’s mother, Bela Rozner. Bela emigrated illegally from Poland around 1939–40, but was recognized by the British Mandate in 1942.

After Finkelstein’s daughter left for college in 2012, Finkelstein wanted to “break the spell” of missed encounters between the women in her family, using this piece to capture the “sense of belonging” they share despite not all having met. Placed side by-side, one notices the likeness shared by these women. Particularly striking, too, is the bold text stating the card’s year of issue, which invokes the approximate time of Bela’s mother’s execution, six years before the State of Israel’s establishment in 1948.

This work gestures towards the history of persecution that also binds these and other women in Finkelstein’s family. Not only was the artist’s grandmother killed during the Holocaust, but so were two of her five maternal aunts as well as her grandfather and two-year-old cousin. Two more of her maternal aunts survived: one was a partisan, another survived Nazi experimentation in Auschwitz and moved to Israel.

Yet the fate of Finkelstein’s grandmother is still largely confined to history. The artist explains that this is in part because her parents didn’t initially talk about this traumatic history, as was usual in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, and because she and her siblings “probably weren’t interested” at the time. Finkelstein also “shied away from studying the Holocaust” until this year, feeling “it was not for [her] to learn because it was in [her] blood.”

Now, Finkelstein is asking important questions about her family’s connection to the Holocaust, but is coming up against another problem: obtaining historical information from archives, which are not always digitized or translated. Art has thus become a key way for Finkelstein to connect to the past in the absence of historical records.

Particularly emotive among Finkelstein’s Holocaust artworks is a photograph in which the artist clutches a framed black-and-white portrait of her grandmother, Gila Rozner, to her chest—the only one in her possession. Simply titled Hug (2013), the image was developed by Finkelstein herself after receiving the negative from her mother, who had stored it in a jewelry box for safekeeping.

There is something particularly intimate about this embrace, despite its simplicity and the fact that it is nonreciprocal. In one sense, this human-to-object hug speaks to the profound absence of Finkelstein’s grandmother, who is unable to participate—at least corporeally—in the act. “It is the only hug I could have with her,” the artist laments. Gazing down at the portrait with her dark hair and clothing, Finkelstein’s appearance is uncannily like Gila’s, who is herself pictured wearing a black button-down coat and shares a similar hair length and style. Yet there is one crucial difference—Gila wears a yellow Star of David, which immediately meets the eye. This Nazi symbol—which is mapped onto the artist’s own body—situates the photograph within the history of the Holocaust.

This embrace also symbolizes the unfaltering connection shared by the two women and demonstrated in The Herstory, as though Finkelstein is reaching into the 1940s to bring past and present into proximity with one another. The mapping of the portrait onto Finkelstein’s torso gestures toward Gila’s central role in shaping Finkelstein’s identity as a Jewish woman. Finkelstein is particularly fond of this piece as a “feminist portrait” that reclaims history and identity, which lie—literally as well as metaphorically—in the hands of the artist.

Finkelstein’s Holocaust art also deals with her status as a Jewish lesbian and immigrant. Her work titled Jew or Homosexual or both?, is a personal reflection on identity, the Nazi system of classification, and persisting antisemitic and homophobic persecution. The piece consists of two colored triangles mirroring those used for identification in German concentration camps throughout occupied Europe. The pink represented homosexual prisoners, the blue represented emigrants. These are overlaid by the number “6,000,001,” which is repeated no less than 30 times and is arranged differently in several fonts. Finkelstein inserts herself into the history of the Holocaust by adding an extra digit to the number 6 million—a reference to the number of Jews who perished during the event. “Which symbol would I wear?” she asks rhetorically, simultaneously implicating herself within this discriminatory practice, while reclaiming these symbols as those of pride.

Ultimately, Finkelstein’s attempts to connect to the past through art reveal the central role artistic expression can play when it comes to questions of history and identity, particularly in the absence of archival records. This is important not only as we approach the so-called post-witness era, in which Holocaust survivors are passing out of living history, but as antisemitism becomes increasingly prevalent in the world today. As a form of activism that blends queer feminist self-expression with a deeply personal traumatic history, Finkelstein’s intersectional approach to art is also a useful reminder of its power.

Hi, I wondet if you could reconect me Rachel...we were friends in 1978 in London.

Thankx

Ursula

Very impressive and interesting view of our, the seconed generationes, may look, see and express himself, for the Holocoset chalange for us.

Thanks a lot for Rachel's' exprestion and Emili Rose overvie of her way of art!