Hannah GreenebaumSolomon

"Who is this new woman?...She is the woman who dares to go into the world and do what her convictions demand. She is the woman who stays at home in the smallest, narrowest circle, foregoing all the world may offer to her, if there her duty lies..."

Hannah Greenebaum Solomon dared to go out into the world and establish the first national association of Jewish women. A superb organizer, Solomon emphasized unity, and orchestrated agreements among Jewish, gentile, and government groups on local, national, and international levels.

Solomon was not only the celebrated founder of the National Council of Jewish Women, but also an important force for reform in turn-of-the-century Chicago. Her work grew out of her sense that "woman's sphere is the whole wide world." But at the same time she believed a woman's primary responsibility was to her family. For Solomon, there was no more powerful role than that of the Jewish mother.

Above all, Solomon's commitment and energy were legendary. As one sister quipped, "We know that it is useless to attempt to stop you in your mad career, that ere the winter has passed, the only field of your activity will be a spot marked by a marble slab bearing the inscription, 'Gone to another meeting. Locality uncertain. Return indefinite!'"

Notes:

- "Who is this new woman..." quote from Hannah Greenebaum Solomon, A Sheaf of Leaves (Chicago: private printing, 1911) 146.

- "women's sphere is the whole wide world..." quote from "American Jewish Women in 1890 and 1920: An Interview with Mrs. Hannah G.Solomon." American Hebrew, April 23, 1920: 748-9.

- "We know that it is useless..." quoted by Solomon in Sheaf 86.

Family Roots

"The Greenebaum home has always been a social and cultural center for the Jewish settlers in Chicago."

Hannah's father, Michael Greenebaum, was part of the earliest group of Jews to settle in the frontier city of Chicago. He had left his small German village at the age of twenty, planning to return after a few years of plying his trade as a tinsmith in America. But after arriving in Chicago in 1847, he realized the young city's immense opportunities, and sent word for two of his brothers to join him. Michael Greenebaum began work as a salesman in the hardware business, and would later become a successful merchant. In 1848, he married Sarah Spiegal, whom he had met in New York while visiting distant cousins. By the time Michael had coaxed the rest of his family to Chicago in 1852, Sarah had already given birth to the first Greenebaum child born in America.

The Greenebaum clan was large, prosperous and very close. Hannah was born on January 14, 1858, the fourth of ten siblings. She grew up in a lively home, always busy with the "coming and going of grandmothers, grandfathers, aunts, uncles and cousins." Michael and Sarah Greenebaum were also a vital part of the community, and well known for their hospitality. As Hannah remembered, "Our dining table was seldom surrounded only by members of the family."

Notes:

- "The Greenebaum home has always ..." quote from Herma Clark, The Elegant Eighties. (Chicago: McClurg, 1941) 59.

- On Michael Greenebaum's early life in America, see Hannah Greenebaum Solomon, Fabric of My Life (New York, Bloch Publishing Company, 1946) 6-8.

- On the Greenebaum brothers Michael, Henry and Elias as part of Chicago's earliest Jewish settlers, see Irving Cutler, The Jews of Chicago (Urbana, Illinois : University of Illinois Press, 1996) 12.

- "coming and going of grandmothers..." quote from Fabric 10.

- "Our dining table was seldom surrounded only by members of the family." quote from Fabric 21.

Childhood Influences

"Even in our formative years, we children of Sarah and Michael Greenebaum were unconsciously affected by their spirit of joyous citizenship in a beloved country whose reverse side, our parents never forgot, imposed civic obligation."

Hannah's parents set an example of strong civic involvement. Her mother organized Chicago's first Jewish Ladies Sewing Society, where they made clothes for the needy. Her father founded the Zion Literary Society, and was a volunteer fireman. Before the civil war, he famously battered down the door of a Chicago jail, demanding freedom for a fugitive slave captured that day.

Hannah was thirteen years old when the great Chicago fire of 1871 decimated the city. Though the Jewish community was particularly hard hit, the Greenebaum house was spared. While thousands were fleeing the fires, Hannah's parents crowded as many families as possible into their home.

The Greenebaums kept a kosher home, and even employed a "Shabbos goya," a Christian woman who lit the fires and performed other religiously prohibited tasks for the family on the day of rest. But Michael Greenebaum also helped found Chicago's first Reform synagogue, and advocated moving the Jewish Sabbath to Sunday because he strongly believed in "the importance of adapting religion to the needs and welfare of people."

Notes:

- "Even in our formative years..." quote from Fabric 18.

- On Hannah's parents civic works, see Fabric 18. For Michael Greenebaum, see Hyman L. Meites, ed, History of the Jews of Chicago (Chicago: Jewish Historical Society of Illinois, 1924) 48, 136.

- On the Chicago Fire and the Jewish community, see Cutler 28-9.

- For the Greenebaums response to the fire, see Fabric 26.

- On the Greenebaum's kosher home, see Fabric 16.

- On Greenebaum involvement in the founding of Sinai as well as other Reform synagogues, see Cutler 17.

- On Michael Greenebaum's radical reform beliefs and "the importance of adapting..." quote, see Fabric 31.

Chicago Woman's Club

"To join an organization of 'women'—not 'ladies'—and one which bore the title 'club', rather than 'society', was in itself a radical step...."

In 1876 Hannah and her older sister Henriette were elected to the elite Chicago Woman's Club. "Our entrance...was significant for the organization as well as for us, as we were not only the first Jewish women invited into it, but were probably the only Jewesses many of the members ever had met." Many of Solomon's ideas for the National Council of Jewish Women stemmed from her experiences with the Chicago Woman's Club.

The club emphasized philanthropy and education, with a course of study that was often as demanding as a first year college curriculum. Solomon, who had been educated at both synagogue grammar school and public high school, was the club's youngest member. The rigorous academic papers she authored included "A Review of Spinoza's Theologico-Politicus" and "Our Debt to Judaism," the first talk on religion ever presented before the club. Years later, columnist Herma Clark depicted the event as a highlight of Chicago's early glories.

Notes:

- "To join an organization of..." quote from Fabric 43.

- "Our entrance into the Chicago Woman's Club..." quote from Fabric 42-3.

- On Solomon's education see Fabric 37.

- On the rigor of the Chicago Woman's Club, see Rogow 61, and Theodora Penny Martin, The Sound of Our Own Voices (Boston : Beacon Press, 1987) 105.

- For Clark's articles, see Herma Clark, The Elegant Eighties. (Chicago: McClurg, 1941) 59.

- Caption to Hannah Greenebaum Solomon, circa 1892: the quote "It cannot be proven that sick children..." is from Sheaf 73.

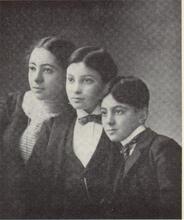

Marriage & Motherhood

"The fabric of my life is now spread out...And through it all...two golden strands appear and reappear..."

Solomon describes the two all-important strands in her life as her family and the National Council of Jewish Women. At the age of twenty-one she married businessman Henry Solomon, and the strand of family completely dominated her early years. She devoted herself to raising her three children—Herbert, Helen, and Frank. "My life was exceedingly full of household tasks...from the time of the coming of the children until they were well along their way, I had divorced myself from outside activities."

When Hannah, in her mid-thirties, began to organize the NCJW, she had the strong support of her husband and children. As she remembered, "My husband's interest and cooperation in everything that I undertook was of the greatest importance to me." Henry often accompanied her on business trips, and the whole family came to Berlin for the International Council of Women Convention in 1904.

Even in her busiest years, family still came first for Hannah. Her autobiography contains more doting reminiscences of children's crayon portraits, her oldest son Herbert's chemistry experiments, and cooking her famous sweet and sour gefilte fish, than it does details of her career. When Herbert died in 1899, at the age of nineteen, Hannah was so saddened that she postponed the Council's Second Triennial for a year.

Notes:

- "The fabric of my life is now spread out..." quote from Fabric 263.

- "My life was exceedingly full..." quote from Fabric 49.

- "My husband's interest ...." quote from Fabric 107.

- On Solomon's reminiscences, see Fabric 49, 67-68.

- On Herbert's death and Triennial postponement, see Fabric 110.

We "Will" Have A Congress

In 1890, Chicago was chosen as the World's Fair exhibition site. The city's inhabitants threw themselves into planning, determined to show the world that Chicago was no prairie town, but a first class metropolis. One year later, the Fair's Board of Lady Managers decided to organize events for women of every religious denomination. The well known, well connected Hannah Greenebaum Solomon was the obvious choice to head the Jewish women.

"Two questions were at first involved: one,—should we have a congress; two,—would it have permanence?...In a flash, my thoughts crystallized to a decision: we will have a congress out of which must grow a permanent organization!" But with no existing associations or lists of Jewish women and without the aid of telephones and modern travel, locating participants was difficult work. Solomon hand-wrote over ninety letters, and her planning committee exchanged "no less than two thousand" over the next two years.

Preparations were in full swing when the men organizing the Jewish Denominational Congress invited Solomon to join their effort. She agreed only if they would "accord us active participation," but as Solomon later joked, "The only part of the program they wished us to fill was the chairs."

Notes:

- On the Chicago World's Fair, see Meites 175-7.

- "Two questions were at first involved..." quote from Fabric 82.

- On the arduous process of reaching speakers and delegates, see Hannah Greenebaum Solomon, "Introduction," Papers of the Jewish Womens Congress (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1894) 3.

- For Solomon's recounting of her meeting with the men planning the Jewish Denominational Congress, see Fabric 83.

- "The only part of the program..." quote from Sheaf 71.

- Caption to Letter to Essayists: The quote, "dozens of Jewesses disclaim affiliation..." is from "Introduction," Papers of the Jewish Womens Congress (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1894) 3.

Jewish Women's Congress

"And if this week we have been spelling 'Jewish Woman' with a capital 'J' and a capital 'W,' it is not vaingloriously nor in a spirit of boasting that we have been rummaging the pages of history for the illustrious daughters of Judah.... In them we have been trying to discover ideals for ourselves, our daughters and granddaughters."

Solomon's years of planning and hard work brought an overflowing crowd of women to the Congress. They "elbowed, trod on each others' toes, and did everything else they could without violating the proprieties," to find standing room in the hall. For four days, speakers like Ray Frank and educator Julia Richman of New York addressed a series of subjects centered on religion, Jewish history and philanthropy.

On the final day, growing enthusiasm culminated in a vote to form the National Council of Jewish Women. A committee quickly drew up a statement of resolutions to define the new organization's goals. Council would work to fulfill its obligations to Judaism through education, fighting anti-Semitism and assimilation, and social reform.

Hannah Solomon was then elected president by acclamation as the entire hall rose, applauding. Despite this unanimous show of approval, when close friend Jane Addams asked Solomon's young daughter, "Helen, wouldn't you like to do what your mother has done?" Helen responded, "Oh no...when I grow up I'm going to be a lady, like my Aunt Rose!"

Notes:

- "And if this week we have spelling..." quote in Sheaf 52.

- "elbowed, trod on each others toes..." quoted in Rogow 19. See American Israelite (7 Sept. 1893): 6.

- On speakers at the Congress, see Fabric 82.

- For information on the general narrative of events, see Rogow 21-24 as well as Papers of the Jewish Women's Congress.

- "Helen, wouldn't you like to do..." quote from Fabric 85-6.

The New Council

"Objections have been made because we are a women's organization. We have not intended to exclude men....We expect to include them whenever they clamor for admission. Up to the present time they have not clamored."

Members of the newly founded National Council of Jewish Women carried the energy and optimism of the World's Fair events back home. By the Council's first Triennial convention in 1896, NCJW was an organization of fifty sections and over 3300 members. Many sections had already founded permanent social service institutions as well as religious education schools for girls. Study Circles, where members discussed the Bible, Jewish culture and history, were flourishing with over half of NCJW's membership participating regularly.

The young Council's identity was still uncertain, but one question was already clear: would it become primarily a religious organization or a women's volunteer agency? For Solomon, philanthropy was an expression of Jewish faith, and an important area of work for NCJW. But she found no reason for a specifically Jewish organization to define itself through social work when non-sectarian charities were equally effective. On the other hand, she saw NCJW's goal of religious renewal as unique. As president, Solomon tried to steer Council towards Judaism as its defining principal.

Notes:

- "Objections have been made because..." quote from Sheaf 140.

- For statistics on Council's membership and philanthropy organization growth, see Rogow 33. On Study Circles, see Rogow 61.

- On Solomon's view that Council's defining identity was its Judaism, note Fabric 80. In the World's Fair's early planning stages, she had chosen to move the congress from the Women's Building to the Parliament of Religions because, "When we use the word 'Jewish' it must have a purely religious connotation."

- On social work as expression of faith, see Sheaf 86-7: "If the deed is the supreme test of religion then does our faith, as exemplified in this branch of our work, reach its highest idea."

- For Solomon's opinion that non-sectarian charities were sufficient, see Sheaf 260-1. Whether this was actually the case could, of course, be contested. Solomon attests in the above report to the fact that she saw no discrimination in the non-sectarian charities serving the Jewish population. Even if this were true, there was often a need for specifically Jewish organizations like the Maxwell House Settlement because some Jewish immigrants avoided Christian social workers in fear they were missionaries.(see Cutler 83)

- Caption to National Council of Jewish Women Kitchen Class for Immigrants: the quote "As an example of what has been accomplished..." is from Sheaf 150.

Radical Or Traditional?

"In the last zigzagging process of world advancement in America, the Jewish men took their wives and daughters by the hand, led them into family pews and left them there..."

The late nineteenth century saw Jewish men yielding their traditional responsibility for religious observance to women. Council members took their new role seriously. They hoped to combat the growing trend of assimilation among American Jews with a renewed commitment to Jewish family life.

Study Circles were a key part of their plan. Women's religious education in the Jewish community was still a radical idea at the turn of the century. But as Solomon and others argued, how could a mother make a traditional Jewish home when she was ignorant of her own culture? Council depicted and believed in its radical step as a means of renewing tradition instead of breaking new ground.

While Solomon was one of the first women to speak from a synagogue pulpit, she still agreed to leave issues of religious authority to men. She did not question the rabbis who praised Council's efforts to renew Judaism while still dictating the meaning of its traditions. Instead Solomon invited the rabbis to lead Study Circles. Even as they boldly trespassed onto new ground, Solomon and the early NCJW maintained that a Jewish woman's greatest power was through influence, not authority.

Notes:

- "In the last zigzagging process of world advancement ..." quote from Sheaf 225.

- On Jewish male leaders approval/disapproval of Council, see Rogow 53; 100-1.

- On Council's radical policy for traditional purposes and on seeking influence, not authority, see Rogow 63.

- Caption to Hannah Greenebaum Solomon Speaking: the quote "...I am not so sure but..." is from Sheaf 225.

Controversy

Despite Solomon's plea to "leave all religious questions to the quarrels of the Rabbis," divisive struggles between NCJW's Reform and Orthodox members developed around the Sunday Sabbath controversy.

Like her father, Solomon personally supported the radical Reform policy of moving the Sabbath to Sunday. She felt that conforming to American custom would encourage more widespread observance. To many Council women who were Orthodox, Conservative, and even some who were Reform, this idea was sacrilege, comparable to a conversion to Christianity. Concerned by Solomon's outspoken opinion, these women determined to force Council to explicitly affirm its support of the historical Sabbath.

Solomon spent much of the first Triennial convention deflecting attempts to raise the question, hoping to avoid the divisive issue. Finally one member moved to block Solomon's re-election, arguing that she could not vote for any woman who did not "consecrate the seventh day as Sabbath." Solomon's response became famous: "I do consecrate the Sabbath. I consecrate every day in the week." The triumphant Solomon was re-elected by acclaim once again.

When Hannah returned home, husband Henry had hung "a huge floral piece on which was written, 'I consecrate every day!'" But Henry's enthusiasm proved overly optimistic, and the troubles surrounding the Sunday Sabbath issue continued to plague Council. NCJW avoided the strife by avoiding religious issues. When Solomon resigned as President in 1905, citing health reasons and the need to rest, Council had shifted its emphasis to philanthropy.

Notes:

- "leave all religious questions to the quarrels of the Rabbis..." quoted on Rogow 104.

- For narrative on events at the first Triennial in general, see Rogow 103-110; specifically, on Sunday Sabbath as sacrilege see Rogow 104.

- The challenge to Solomon and her response quoted on Rogow 106-7.

- "a huge floral piece on which was written..." quote from Fabric 107.

- On avoidance of religious issues as a factor in Council's shifting identity, see Rogow 111-2.

Ardent Expansionist

As a leader, Solomon focused on building consensus and fostering collaboration. She was keenly aware of how cooperation among organizations increased their efficiency and power. As she joked in one speech, "It is evident...that the president of the Council of Jewish Women is an ardent expansionist." When NCJW joined the National Council of Women in 1894, Solomon called it an important first step. She saw no reason why Council's Jewish identity should preclude it from working with compatible Christian groups towards social change.

Solomon's unifying vision was also her greatest contribution to the early, disorganized social welfare system in Chicago. She created structures to monitor available services, avoid overlap and fill in gaps. One of the most important organizations Solomon founded was the Bureau of Personal Service in 1897. During the thirteen years she served as the Bureau's head, she coordinated and implemented relief efforts among agencies working with Jewish immigrants in the "heart of the so-called 'Ghetto' district."

One influential seventh ward collaborator was Jane Addams, Solomon's close friend and colleague. Addams founded Hull House, a pioneering example of the settlement house movement in the early 1900's. Settlements served as cultural community centers and helped organize neighborhood involvement. At Hull House, Solomon estimated, "seventy per cent of those who love to cross its threshold" were the poor Jewish immigrants.

Notes:

- "It is evident that the president..." quote from Sheaf 151.

- On Solomon's ideas on collaboration between NCJW and organizations of other faiths, see Sheaf 120, 129 and Fabric 107.

- For the description of the Bureau and its work, see Fabric 94-5 5. On Hull House and Jane Addams, see Mary Lynn McCree Brian and Allen F. Davis, eds., 100 Years at Hull-House (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1990) 7-8.

- "seventy per cent of those who love.." quote from Sheaf 261.

- Caption to Jane Addams and Hannah Greenebaum Solomon: the quote "I consider Jane Addams the greatest..." is from Fabric 226.

Jews Among Women

As Council grew, it came to represent the voice of Jews among American women's associations. Affiliation with these groups was extremely important to NCJW's middle class, German-Jewish women, signaling their acceptance among the wealthy, gentile elite. But unlike white Christians, Council members did not have the luxury of identifying primarily as women. Rising anti-Semitism forced them to continually defend their Jewish identity.

A striking example of Council's different priorities was their lack of support for suffrage. In 1917, NCJW rejected a proposed resolution advocating women's voting rights. Solomon, now Honorary President, was an adamant proponent of the suffrage movement and close friends with Susan B. Anthony. But even her endorsement did not sway Council.

For the NCJW, isues like Jewish immigrant aid and America's entry into World War I took precedence over women's rights. Members also had good reason to distrust the women's suffrage movement. Writers like Elizabeth Cady Stanton saw Judaism and Christianity as the forces behind women's oppression and called for the abandonment of both religions. Other feminists of the time blamed the oppressive parts of Christianity on its Jewish roots.

Most importantly, Council continued to justify its work as an extenstion of the traditional role of the Jewish mother. From their point of view, Jewish women did not need the power of the ballot box to play an active role in changing society.

Notes:

- For discussions of NCJW and its relationship to the women's suffrage movement, see Rogow 80-1 and Deborah Grand Golomb, "The 1893 Congress of Jewish Women: Evolution or Revolution in American Jewish Women's History?" American Jewish History 70 (September 1980): 55-7. Golomb writes, for example, "The Women's Bible, a collection of commentary on biblical passages pertaining to women (published in 1898) by Stanton and others, made disparaging references to Jews. A typical comment was one by Ellen B. Dietrick concerning the disparity between two creation myths. 'My own opinion is that the second story was manipulated by some Jew in an endeavor to give 'heavenly authority' for requiring a woman to obey the man she married.'" (56)

Public Welfare

"Now, as I think back, I am dismayed to remember how ill-equipped we women were for some of the work we did! ....Yet so it must have been, for surely Miss Vittum spoke the truth when she said, 'And there...[touring] of one of the city's most unsavory dumps, was our Mrs. Solomon, clad in a trailing gown of white cotton lace and clutching in her white-gloved hands a matching parasol!'"

Despite the limiting fashions of the day, Solomon was indefatigable in her active civic involvement. Her many positions included serving as President of the Illinois Industrial School for Girls, a role that affected her "more deeply than that [of any other]." This institution for wards of the state had fallen into disrepair due to a lack of funds. As president, Solomon liquidated the school's large debt in one year. She quickly improved care for the girls, and began developing a farm in Chicago's suburbs into a new, model campus for the school.

Solomon's concern for children's rights also encompassed the problems of juvenile delinquency. She saw that crimes against children were "not punished severely enough," and that "Dependents were often lodged in poor-houses; minors were confined for slight misdemeanors, and placed in police stations and jails, in the company of hardened criminals." In response, Solomon worked to institute Chicago's first Juvenile Court, and to improve the city's laws concerning children.

Notes:

- On Solomon and the Women's City Club and as chairman of City Waste, see Fabric 167-8.

- For Solomon's quote, "Now, as I think back, I am..." see Fabric 168.

- For Solomon's work with the Illinois Industrial School for Girls and the quote, "No project ever affected me more deeply than...," see Fabric 151.

- On Solomon and her work on the problems of juvenile delinquency, see Fabric 155-8.

- "Crimes against children were not punished severely enough..." quote from Fabric 156.

A Powerful Legacy

"We must add our voices to those who cry out that there is a standard below which we will not allow human beings to live, and that that standard is not at the freezing nor starving point....In a democracy all are responsible."

Solomon saw commitment to social welfare as her responsibility—as a Jew, an American, and a woman. She believed no life was complete which had not taken light "from the bright places in its own and transmitted [it] into homes of sorrow and gloom, dividing the fullness of earth with those whose portions are nothingness."

In her later years, as well as after her death, she was celebrated again and again for her trailblazing work. The National Council of Jewish Women still evokes Solomon's words as an inspiration to "[improve] the quality of life for women, children, and families … by safeguarding individual rights and freedoms."

Solomon spoke boldly and with conviction in an era when Jewish women's voices were rarely heard. At the same time, she advocated a return to the traditions of Jewish motherhood. Ironically, Solomon helped perfect the tools later generations would use to challenge these and other traditions. Her example of powerful speech and organization paved the way for new, more radical possibilities.

Notes:

- "We must add our voices to those..." quote from Sheaf 189.

- "No life is complete..." quote from Fabric 159.

- The NCJW Mission statement has evolved over time. The current, slightly evolved "Mission Statement" is available online.

Media

Timeline

Michael Greenebaum arrives in Chicago

Michael Greenebaum and Sarah Spiegal marry

Hannah Greenebaum Solomon born, January 14

Hannah and sister become first Jewish members of Chicago Woman's Club

Marries Henry Solomon

Jewish Women's Congress at the Chicago World's Fair;

NCJW founded

First NCJW Triennial held in New York City

Son Herbert dies

Retires as NCJW president, elected Honorary President

Becomes President of Illinois Industrial School for Girls

Honorary Chair with Jane Addams of International Council of Women's Convention in Toronto

Helps found the Chicago Women's City Club;

Serves as Chairman of City Waste

Appointed Honorary Chairman of the Joint Committee on Motion Pictures;

Publishes Sheaf of Leaves, a collection of essays, speeches and writings

Husband Henry dies

US enters WWI;

Solomon chairs City Ward Leaders' Committee

Embarks on a world tour;

Visits Henrietta Szold in Palestine

Dies in Chicago on December 7 at age of 84

Autobiography, Fabric of My Life, is published posthumously

Bibliography

Published Sources

American Hebrew, May 31, 1895.

American Israelite, September 7, 1898.

"American Jewish Women in 1890 and 1920: An Interview with Mrs. Hannah G. Solomon." American Hebrew, April 23, 1920: 748-9.

American Jewess, December 1886.

——, April 1898.

Baum, Charlotte, Paula Hyman, and Sonya Michel. The Jewish Woman in America. New York: New American Library, 1977.

Berrol, Selma. "Class or Ethnicity: The Americanized German Jewish Woman and Her Middle Class Sisters in 1895." Jewish Social Studies 47 (Winter, 1985): 21-32.

Breckinridge, Sophonisba Preston. The Delinquent Child and the Home. New York : Arno Press, 1970.

Brian, Mary Lynn McCree and Allen F. Davis, eds. 100 years at Hull-House. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1990.

Chicago City Homes Association. Tenement Conditions in Chicago. Text by Robert Hunter. Chicago: City Homes Association, 1901.

Clark, Herma. The Elegant Eighties. Chicago: McClurg, 1941.

Cutler, Irving. The Jews of Chicago : From Shtetl to Suburb. Urbana, Illinois : University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Elwell, Ellen Sue Levi. The Founding and Early Programs of The National Council of Jewish Women. Ph.D. diss. Indiana University, 1982.

Golomb, Deborah Grand. "The 1893 Congress of Jewish Women: Evolution or Revoltuion in American Jewish Women's History?" American Jewish History 70 (September 1980): 52-67.

Gutstein, Morris A. A Priceless Heritage. New York: Bloch Publishing Company, 1953.

Hard, William. The Women of Tomorrow. New York: The Baker and Taylor Company, 1911.

Kaiser, Alois. A Collection of the Principal Melodies of the Synagogue, From the Earliest Times to the Present. Chicago: T. Rubovits, 1893.

Kirkland, Wallace. The Many Faces of Hull-House. Mary Ann Johnson, ed. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Kuzmack, Linda Gordon. Woman's Cause. Colombus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1990

Martin, Theodora Penny. The Sound of Our Own Voices. Boston : Beacon Press, 1987.

Meites, Hyman L., ed. History of the Jews of Chicago. Chicago: Jewish Historical Society of Illinois, 1924.

National Council of Jewish Women. The First Fifty Years. National Council of Jewish Women, 1943.

Papers of the Jewish Women's Congress. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1894.

Proceedings of the National Council of Jewish Women at New York. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1897.

Rogow, Faith. Gone to Another Meeting. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1993.

Solomon, Hannah Greenebaum. Fabric of My Life. New York, Bloch Publishing Company, 1946.

Solomon, Hannah Greenebaum and Sadie American. "National Council of Jewish Women." Reform Advocate, January 30, 1897.

Sochen, June. Consecrate Every Day. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 1981.

Thirtieth Annual Announcement of the Chicago Woman's Club. Chicago: Blakely Printing Co, 1907.

Wenger, Beth S. "Hannah Greenebaum Solomon." Jewish Women In America. Vol. 2. Paula E. Hyman and Deborah Dash Moore, eds. New York : Routledge, 1997. 1283-1286. Reprinted in Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, 2005.

Archival Sources

Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

Chicago Historical Society. Chicago, IL.

Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives. Cincinnati, OH.

Library of Congress. Washington, DC.

National Council of Jewish Women. New York, NY.

New York Public Library. New York, NY.