Young Women's Hebrew Association

The immediate precursor of the Young Women’s Hebrew Association movement was the participation of women in the life of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in the nineteenth century. A truly independent women’s association did not appear until after the turn of the twentieth century, when a new YWHA was established in New York City in early 1902. Its principal founder and guiding spirit was Bella Unterberg. From the start, its primary aim was to provide social recreational activities for Jewish working girls, and it was an immediate success. The essential factor setting the new YWHA apart from the YMHA was its pronounced Jewishness.

Background

Judging by the name alone, it might seem that the Young Women’s Hebrew Association (YWHA) was the women’s version of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) and nothing more. But just as the YMHA was no mere knockoff of its Christian namesake, so too was the idea of the YWHA both a borrowing and an innovation. As a communal agency run entirely by and for women, the YWHA provided an important political arena for Jewish women in the early part of the twentieth century. As a pioneering Jewish institution combining social and religious services, the YWHA became one of the principal sources of the Jewish community center movement.

The Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), certainly a key inspiration for the YMHA movement, was introduced to America in 1851. Four years later, a women’s analogue—the YWCA—was instituted as well. Spreading rapidly across the country, the YM-YWCA movement provided young men and women with an ecumenical social center. Yet it also came to function as a young people’s church and virtually became a Protestant denomination of its own. YMHAs, on the other hand, were first established during the 1850s on the model of Jewish young men’s literary associations and benevolent societies. The first major YMHA institution was founded in New York City in 1874. It too eschewed religious services and emphasized the cultural uplift of young men; that is, the YMHA grew out of educational precedents in its own community and was furthermore distinct from the YMCA in its secular orientation. Rather than resting on a religious basis, the YMHA movement sprang from ethnic and cultural motives and was integral to the late nineteenth-century revival of Jewish life.

Following the onset of mass immigration in the 1880s, the YMHA came to be employed as an agency of Americanization. Hence in 1883, the New York YMHA established a branch downtown in the immigrant district of the Lower East Side, said to be “the first Jewish neighborhood center in America for immigrant groups.” Six years later, the downtown YMHA joined with two other educational agencies to form the Hebrew Institute. Soon renamed the Educational Alliance, it became the premier Jewish settlement of the Lower East Side and the flagship institution of a nationwide movement. The YMHA thus played a significant role in the emerging settlement movement, an institutional trend largely led and staffed by women. Thus, the first Young Women’s Hebrew Association was founded in New York City in 1888 for the purpose of immigrant education. Under the presidency of public-school educator Julia Richman, this early YWHA—the first time the name appeared—remained for only a few years and was never more than auxiliary to the YMHA.

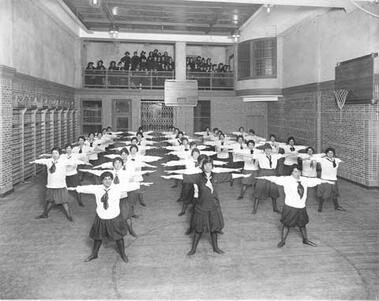

The immediate precursor of the YWHA movement, therefore, was the participation of women in the life of the YMHA. Early on, women were admitted to some YMHA activities on a limited basis, such as the “musical and dramatic corps which included young ladies” at the YMHA in Lafayette, Indiana, in 1868 and the class in elocution and English literature of the Philadelphia YMHA, which permitted women to join in 1876. Whereas the New York YMHA voted against the admittance of women in 1874, other YMHAs proved more liberal. The YMHAs of Chicago and Philadelphia voted to admit women as full members in 1877 and 1880 respectively, and in 1878, a YMHA in Wisconsin changed its name to Madison Hebrew Association in order to include women. Following the 1888 establishment of the YWHA auxiliary in New York, similar women’s auxiliaries were organized in cities around the country, including Louisville, Kentucky; Denver, Colorado; New Orleans, Louisiana; Columbus, Ohio; Birmingham, Alabama; and Washington, D.C. Women’s participation in YMHA activities soon expanded, as when the Louisville YMHA instituted gymnasium classes for women in 1891.

Foundations and Development of YWHA

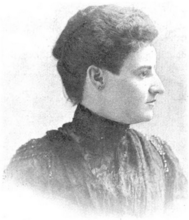

A truly independent women’s association did not appear until after the turn of the century, when a new YWHA was established in New York City in early 1902. Its principal founder and guiding spirit was Bella Unterberg (née Epstein), the wife of shirt manufacturer and Jewish philanthropist Israel Unterberg. Born in 1868 to a Russian Jewish immigrant family (her father had arrived in the United States in 1855 and fought in the Civil War), Unterberg received both a New York City public school education and a sound Jewish upbringing. As a young woman in her twenties, she was profoundly affected by the efflorescence of Jewish women’s social activism during the 1890s. Supporting and supported by the parallel efforts of her husband, Unterberg became a communal leader in her own right, directing campaigns for the Ladies’ Fuel and Aid Society and the Women’s Committee of the Council for National Defense. But it was the YWHA that became her foremost concern and “favorite child.” She became so closely identified with the YWHA, in fact, that her biographer could quite rightly state: “The story of the YWHA is from the beginning the story of Mrs. Unterberg, its record Mrs. Unterberg’s record, its triumphs and achievements, her triumphs and achievements.”

The institution had its beginnings in a meeting called by Unterberg on February 6, 1902, and held in her home at 143 West 77th Street. The eighteen women present elected Unterberg as president, Mrs. Henry Pereira Mendes as vice president, and Mrs. Simon Liebovitz as treasurer. Mendes was the wife of the Synagogue cantorhazzan of the Spanish and Portuguese synagogue, Shearith Israel, and in addition to the vice presidency was elected “religious guide” of the organization. Regarding its mission, Unterberg recommended “that the Society establish an institution akin in character to the YMHA but combining therewith features of a religious and spiritualizing tendencies.” The minutes conclude: “After considerable discussion on the question of the Society’s name, it was agreed that it be called and known as the Young Women’s Hebrew Association.”

So, the new institution would be modeled after the YMHA as a community center dedicated to the uplift—both social and spiritual—of young Jews. In Unterberg’s view, the best way to reach young people was “by thoroughly fraternizing and associating with them and by placing before them opportunities of pleasant and refined social pleasures to attract them gradually to better, nobler and more spiritual ideals.” By the beginning of 1903, the YWHA had rented a building at 1584 Lexington Avenue and soon established itself as a vital community center in the burgeoning Jewish neighborhood of Harlem. From the start, its primary aim was to provide social recreational activities for Jewish working girls. As such, it was an immediate success, recording a total attendance of over twenty-one thousand in its first year alone. Unterberg soon recognized the need for larger quarters and in 1906 rededicated an expanded and renovated facility. The building could now house eighteen female residents and would henceforth become a boarding home as well as a community center. At the dedication, Unterberg asked those assembled: “Can you imagine doing a greater good than supplying hundreds of hard-working girls with a chance of bettering their condition and of helping them, in many cases, from a condition of want and necessity to a place in the world where they can become independent and self-supporting?” Under her beneficent direction, the new YWHA was a kind of social settlement house for young working Jewish women.

Differences From YMHA

The essential factor setting the new YWHA apart from the YMHA was its pronounced Jewishness. While the YMHA movement had given some attention to the observance of Jewish religion and the preservation of Jewish identity, its guiding ethos was not Judaism but Americanism. Following the turn of the century, many Jewish women rebelled against this emphasis and made their version of the settlement house a positive force for Jewish life. This was part of a general backlash against the assimilationist tendency of the first quarter century of mass immigration, but it was also part of a women’s movement for the “Judaization” of American Jewry. In her address at the dedication ceremony of the YWHA building in February 1903, Rebekah Kohut “laid stress upon the necessity of having religion as the foundation stone of the new organization, and paid a tribute to the religious work now being done by the YMHA.” A 1912 newspaper article quoted Sophia Berger, superintendent of the YWHA: “Back of all that we do, is the thought of preserving the essential Jewishness of our people. As Jews we want to save our Judaism. As Jews we bring these girls in here that they may find shelter and help and find, too, the God of their fathers.” And at the dedication exercises of the new YWHA building in 1914, Augusta Wolf, representing the younger members of the organization, urged that “the new home be made distinctly a center for the propagation of Jewish ideals, Jewish traditions, Jewish culture and Jewish religion.” The special care of the association, she declared, was “to make Jewish girls grow up into Jewish women.”

All agreed that the keynote of the YWHA was Judaism, and thus the YWHA included a synagogue on its premises from early in its history. The YWHA synagogue functioned as an independent congregation catering to the surrounding community, not as a women’s congregation as such. To suit the constituents of that highly Americanized immigrant neighborhood, it offered a modernized Orthodox service—the traditional liturgy but with an English sermon, mixed seating, and choral music—a new religious mix that soon would be called Conservative Judaism. Apparently, such innovation could be accepted more readily in a women’s institution. In the new building of 1914, the auditorium doubled as the synagogue, and services were conducted every Friday night, Saturday morning, and on Jewish holidays. The other major Jewish aspect of the YWHA was its curriculum consisting of classes in Hebrew, Bible study, and Jewish history. This was coordinated with an experimental Hebrew school for girls conducted at the YWHA by the Bureau of Jewish Education (of the New York City Kehilla).

Of course, the YWHA offered far more than religious services and Hebrew classes. In 1917, a few years after the completion of its new eight-story facility on 110th Street overlooking Central Park, the New York YWHA was described as “the only large institution of its kind in America.” The description of the modern social center continued: “Besides being a most comfortable home for one hundred and seventy girls, the building is also a true center for the communal interests of the neighborhood; it houses a Commercial School, a Hebrew School, Trade Classes in Dressmaking, Millinery, Domestic Science, classes in Hebrew, Bible Study, Jewish History, Art, English to Foreigners, Advanced English, French, Spanish, and Nursing. There is a completely equipped modern gymnasium and swimming pool.” Serving both its residential population and the larger community, the YWHA became a full-service Jewish center. Housing both a synagogue and a swimming pool, the YWHA was nothing less than a “shul with a pool”—an early exemplar of the synagogue center movement (Mordecai Kaplan’s Jewish Center did not appear until three years later).

Additional amenities included “musical salons” held on Sunday evenings and weekly dances for young women and men on the outdoor roof garden, which proved to be especially popular. The roof was also used during the summer for day care programs for “anemic and cardiac children, and the children of poor families.” The YWHA also sponsored summer camping, including hiking, canoeing, and all manner of sporting activities. Back in the city, athletics was fostered in classes in swimming, tennis, fencing, and so on. Dance was especially popular, being offered in several varieties. An employment bureau was provided for young women in need of jobs, and during World War I, the YWHA cooperated extensively with numerous war relief efforts. Finally, the earlier emphasis on immigrant adjustment was retained but from a more sympathetic point of view: “An important work to which a great deal of attention has been paid is the formation of Americanization Classes for Aliens, to help lessen the tragedy in the social evolution of the immigrants.”

Growth

Following the success of the New York YWHA, new YWHAs were soon established around the city: the West Side YWHA in 1914, the YWHA of Brooklyn in 1916, and the YWHA of Brownsville in 1917. Around the country, the women’s auxiliaries of the earlier period began to be replaced by independent YWHAs. The spread of the movement was so rapid that regional federations of YWHAs began to appear. The first was the Associated YWHAs of New England, organized in 1913. The Metropolitan League of YWHAs of New York City and the New Jersey Federation of YWHAs soon followed. Partly as the result of the acceleration of the YWHA activity, the YM-YWHA movements were organized on a national basis when the Council of Young Men’s Hebrew and Kindred Associations (CYMHKA) was established in 1913. The development came at the expense of YWHA independence, however, as YWHAs began to merge with their male counterparts.

In 1919, the CYMHKA listed 294 constituent organizations, of which some 127 were YWHAs—the majority being in New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts. As above, most of these existed alongside YMHAs. Out of a total 127 YWHAs, forty-six shared the same address with YMHAs, nineteen were ladies’ auxiliaries to YMHAs, and eight were listed as part of a combined YM-YWHA. On the other hand, twenty-three YWHAs enjoyed their own separate facilities and fifteen were independent institutions without a neighboring YMHA (though some were affiliated with the local Jewish settlement). Cities thus monopolized by a YWHA included Los Angeles, California; Atlanta, Georgia; Lewiston, Maine; Baltimore, Maryland; Fitchburg, Massachusetts; Cincinnati, Ohio; Johnstown, Pennsylvania; and Galveston, Texas.

The turning point was the 1921 absorption of CYMHKA by the Jewish Welfare Board (JWB), which took as its mission the formation of all-inclusive Jewish community centers. Independent agencies such as the YWHA were thereafter encouraged to merge with similar institutions. With the prompting of the JWB staff, no fewer than fifty-three YWHAs merged with their brother associations to form combined YM-YWHAs during the years 1921 to 1923, a pattern that continued in the years to come. The original independent YWHA of New York City resisted the trend until 1942, when its building on 110th Street was leased to the United States Army as a barracks and its activities were moved to the YMHA building at Ninety-second Street and Lexington Avenue. Three years later, the two groups merged by reincorporating the YMHA as the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association. The former YWHA was reincorporated as the Jewish Association for Neighborhood Centers, a local version of the JWB.

The New York YWHA had existed as an independent institution for over forty years and during that time it gave rise to a national movement. Unterberg founded the movement in 1902 and served conspicuously as the lone woman on the CYMHKA and on the board of the JWB. She remained the president of the YWHA until 1929, when she was succeeded by vice president Frieda Schiff Warburg (daughter of Jacob Schiff, the main benefactor of the YWHA, and wife of Felix Warburg, the president of the YMHA, among their many other philanthropic activities). Under the leadership of these two remarkable women, the independent YWHA gave thousands of young Jewish women a home of their own in the big city, creating a women’s sanctuary in a male world—no small achievement. Resting on the foundations of the YM-YWCA, the YMHA, the settlement house, and other philanthropic agencies, the YWHA was innovative in its own right. Its integrated program of religious, education, and social services became a principal model for the synagogues and Jewish centers of today. The Young Women’s Hebrew Association was, it might be claimed, the original Jewish community center.

Goldwasser, I.E. “The Work of Young Men’s Hebrew and Kindred Associations in New York City.” Jewish Communal Register (1917).

Israel and Bella Unterberg—A Personal and Communal Record (1932); Kaufman, David. “The YMHA as a Jewish Center.” In “ ‘Shul with a Pool’: The Synagogue Center in American Jewish Life, 1875–1925.” Ph.D. diss., Brandeis University, 1994.

Ninety-Second Street Y. Archives. Record group 5, Young Women’s Hebrew Association, NYC.

Rabinowitz, Benjamin. “The Young Men’s Hebrew Associations,” PAJHS 37 (1947).