Solomon’s Judgment: Bible

In this story, King Solomon is asked to consider the case of two women who gave birth to sons but, due to the death of one of their children, are fighting over the remaining child. The true parentage of the living child is revealed when Solomon decides to have the baby split in half and the baby’s true mother protests, while the other supports and even encourages his judgement. While the story is generally cited as an example of Solomon’s wisdom, this narrative also shows the strength of maternal love.

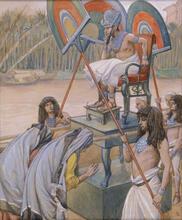

Solomon’s Judgment

Immediately after he requests that God grant him “an understanding mind to govern your people” (1 Kgs 3:9), King Solomon (reigned c. 968–928 BCE) is confronted by two prostitutes and their enigmatic case. One function of the story, therefore, is to illustrate God’s fulfillment of Solomon’s plea. The story further demonstrates that Solomon provides access to justice even to the most marginalized of Israel’s subjects, in this case women bereft of male benefactors, whether husband or father.

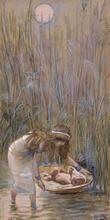

The narrator informs the reader at the outset that these women are prostitutes, so that the lack of a corroborating witness in their home is understood; in ancient Israel, one would expect to find a husband in the home of a woman after childbirth. Further, the tale expresses the intensity of maternal affection, which exceeds jealous possessiveness. (Moses’ mother, in Exodus 2, behaves similarly in renouncing her claim to her child in order to save his life.) The fact that these women are prostitutes only strengthens the depiction of authentic love (or envy), as the live son is not desired as an object to win the affections of a husband, but rather for his own sake.

The narrator presents us with two women, referred to vaguely as “the one woman” and “the other woman.” We know nothing of their appearance and can distinguish between them only by their words. The “one woman” offers a full version of the events, that she and “the other woman” gave birth to sons only three days apart.

The rest of her account, however, provides only logical speculation as she herself admits that she was asleep (v. 20) during the episode. She claims that the other woman unintentionally killed her baby by lying on it and then exchanged the dead baby for her live son. Since no other people were at home, the reader (and the king) has only the perspective of her version, a reconstruction of events that happened as she slept so soundly that she did not perceive the switch. She assumes that her companion’s negligence caused her baby’s demise, because he had shown no symptoms of illness previously; if he did, perhaps witnesses could have been called to verify his condition.

The other woman does not dispute this account but states briefly, “No, the living son is mine, and the dead son is yours” (v. 22). It is difficult for the reader to sympathize with her because of the terseness of her words. Rather than summon character witnesses, cross-examine the women, pursue physical evidence, or even take time to ponder the dilemma, the king calls for a sword and gives directions to one of his courtiers to divide the live baby in two and give each woman half.

At this point the narrator identifies for us the mother of the living child—the woman who offers her son to her counterpart in order to save him.

The Mothers’ Motivations

The reader, however, does not know whether the mother of the live child is the first or the second woman, the complainant or the respondent. The conventional and most probable understanding of the story is that the first woman, who gave the speculative yet full account of what transpired, is the mother of the living child. Her spontaneous outburst is motivated by the “compassion for her son [that] burned within her” (v. 26). The Hebrew word translated as “compassion,” rahamim, is related to rehem, “womb,” and is especially suitable for evoking maternal pathos. The narrator assumes that strong, spontaneous emotion offers a reliable reflection of a person’s true nature.

What motivates the other woman to demand the splitting of the child even after her rival, at least verbally, surrenders him? Perhaps fierce envy prompts her to demand that her housemate’s child suffer the same tragic fate as did her own child. Because she is not his real mother, her desire for vengeance transcends her love for the child. Further, she may fear that her claim to the child will never be secure, or she may be seeking to flatter the king by affirming his judgment. By exposing the falseness of her claim, Solomon’s ruse amazes his subjects and demonstrates his God-given wisdom in executing justice.

Bird, Phyllis. “The Harlot as Heroine: Narrative Art in Three Old Testament Texts. In Amihai, Miri, and George W. Coast, eds. Narrative Research on the Hebrew Bible, edited by Miri Amihai and George W. Coast, 119-40. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1989.

Camp, Claudia V. Wise, Strange and Holy: The Strange Woman and the Making of the Bible. Vol. 9. A&C Black, 2000.

Lasine, Stuart. “The Riddle of Solomon’s Judgment and the Riddle of Human Nature in the Hebrew Bible.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 45 (1989): 61–86.

Lasine, Stuart. “Solomon, Daniel, and the Detective Story: The Social Functions of a Literary Genre.” Hebrew Annual Review 11 (1987): 247–266.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Reinhartz, Adele. “Anonymous Women and the Collapse of the Monarchy: A study in narrative technique.” In Feminist Companion to Samuel and Kings, edited by Athalya Brenner, 43-65. Sheffield Academic Press, 1994.

van Wolde, Ellen. “Who Guides Whom? Embeddedness and Perspective in Biblical Hebrew and in 1 Kings 3:16–28.” Journal of Biblical Literature 114 (1995): 632–642.