South Africa

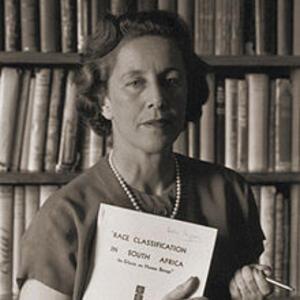

Courtesy of David Saks, South African Jewish Board of Deputies.

During the late nineteenth century, South African Jewish women were as subject to patriarchal attitudes as women everywhere. From the early twentieth century, they exhibited increasing activism in national politics; they used their organizational skills in Zionist and welfare fields in particular. By the early twenty-first century, many more women had attained leadership and/or senior positions both within and beyond the Jewish community. Over the last half-century, the community has become significantly more internally diverse, especially regarding religious practice and attitudes to Israel, and since democracy in 1994, many have become more involved in the wider society. Despite demographic decline, the community—paradoxically, and in part because of women’s activities—continues to exhibit remarkable vitality and resilience.

In South Africa, the lives of all citizens, including those in the Jewish community, have been shaped by the country’s colonial segregationist and subsequent apartheid policies, as well as its post-1990 struggle to unravel those iniquitous systems. After a brief look at the community’s founding and characteristics, this article focuses on the roles that Jewish women assumed within and beyond that community, both historically and in recent times.

The Jewish Community in Brief

The South African Jewish community is highly organized and relatively affluent. At its 1970 zenith, the community numbered 118,200 (0.6 percent of the total population of 21.4 million and 3.1 percent of the white population of 3.7 million). Subsequent surveys reveal a steady decline in the Jewish population, mainly through emigration. The 2019 survey estimates the Jewish population at just 52,300 (0.09 percent of the total population of 58.8 million). Eighty-nine percent of Jews live in the largest cities—Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Durban—while small and diminishing populations live in Pretoria and Port Elizabeth, with tiny scatterings elsewhere. However, despite its small size and continuing losses from emigration, the Jewish community overall exhibits remarkable vitality, continually initiating new organizations and programs.

The community has long resembled other (especially Western) Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora Jewish communities, with its immigrant origins, pro-Israel stance, vigilance against antisemitism, and concern to promote Jewish cultural continuity and counter assimilation. Yet, it is different from other communities regarding its origins, relative internal homogeneity, level of Zionist commitment, and low intermarriage rate.

Settlement History

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Jewish immigrants arriving in South Africa encountered a linguistically, racially, and culturally diverse local population that provided social space for minorities, which both facilitated and reinforced Jewish collective identity. In addition, by virtue of their skin color, Jewish immigrants benefitted from the prevailing racially exploitative system. Despite a brief moment when their “whiteness” was questioned, they became (minority) members of a privileged and dominant class.

The 40,000 or so Eastern European Jews who arrived between the 1880s and 1914 included an array of socialists, pietists, Zionists, and Bundists, similar to the mix in many East European societies. Yet a disproportionate number were from Lithuania, making the community unusually homogeneous. Hasidism was virtually absent until the 1970s, a distinctive form of Yiddish was spoken, and distinctively Lithuanian Jewish foods and customs prevailed. Moreover, east Europeans’ lack of exposure to Reform Judaism meant that Progressive/Reform Judaism was established only in 1930.

By 1948 another 30,000 Jews had immigrated to South Africa, again mostly from Eastern Europe, despite the restrictions of the country’s 1930 Quota Act. As Germany was not among the nations specified by the Act, about 6,000 Jews fleeing Nazi Germany also entered South Africa between 1933 and 1939.

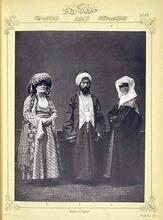

During the 1960s, Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardi Jews originally from the Aegean island of Rhodes and both Sephardim and Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazim from Israel joined the community. Although the Sephardim established their own congregations and maintained many Sephardic traditions, both they and the Israelis were largely integrated into the predominantly Ashkenazi community. By 2019, eighty-nine percent of the community’s members were South African born and ninety-six percent were citizens of the country.

Major Communal Structures

In 1896 the first Members of Hibbat ZionHovevei Zion Society was formed in South Africa and a resolution establishing the South African Zionist Federation (SAZF) was passed in 1898, one year after the first Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. Significantly, Zionists created a country-wide organizational framework before a representative Jewish organization was formed to liaise with local authorities. Over time, South African Jewry has continued to demonstrate high per capita ratios on various “Zionist” (pro-Israel) indices: number of female/sing.; individual(s) who immigrates to Israel, i.e., "makes aliyah."olim, or people emigrating to Israel; proportion affiliated with Zionist organizations; amount of financial contributions to Israel; number of people visiting Israel and frequency of visits; and number of youth involved in Zionist youth programs or who have studied in Israel.

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies, modelled on the British equivalent, was created in 1912 through an amalgamation of the Transvaal and Natal Board (founded 1903) and the Cape Board (founded 1904). The board positions itself and is accepted by government as the community’s “umbrella representative spokesbody and civil rights lobby.” Other Jewish organizations in the country affiliate with it.

Religious Affiliation and Ethnicity

Through most of the community’s history, Jews have overwhelmingly affiliated with the Orthodox movement. In a 2019 survey, a majority (62 percent) self-identified as traditional or Orthodox, fourteen percent as secular/cultural, and nine percent as Progressive/Reform. Religious tensions have been minimal, despite the Chabad/Lubavitch influence increasingly evident in synagogues and educational institutions since the 1970s and the presence of Ohr Somayach (a network of Haredi institutions focusing on returnees to Orthodox Judaism) in Johannesburg and Cape Town since the late 1980s.

What constitutes “orthodoxy,” however, has changed over time, markedly more so in Johannesburg than in Cape Town. As the 2019 survey indicated, 48 percent in Johannesburg described themselves as Orthodox or strictly Orthodox, with eighteen percent declaring they were secular/cultural. In Cape Town, 22 percent said they were Orthodox or strictly Orthodox and 40 percent said they were secular/cultural. Furthermore, twelve percent of all married South African Jews are married to non-Jews, while the respective proportions for Johannesburg and Cape Town are six percent and eighteen percent. Interestingly, among those who live together but are not married to each other, the prevalence of a non-Jewish partner is 60 percent. Furthermore, 80 percent of Johannesburg’s Jews claimed that more than half their friends are Jewish, whereas the corresponding figure for Cape Town was 60 percent. Despite these differences, in both cities and overall, more than 80 percent completely agreed with the statement “I am proud to be a Jew.” Respondents said they have a “sense of belonging to the Jewish people” and feel “connected to and responsible for other Jews.”

That 75 percent of Jewish school-age children attended private Jewish day schools in 2019 is another indicator of ethnic awareness. The majority attend schools that are part of a self-styled “national-traditional” network that is Zionistic. The descriptor “traditional” indicates acceptance of all who self-define as Jewish (although some of these schools also accept non-Jewish children). South Africa’s first and now largest modern Orthodox religious day school was established in Johannesburg in the mid-1950s. The 1970s and 1980s saw several other religious schools established in Johannesburg, and three have opened in Cape Town since 2006. By the 2020s, Johannesburg also had several schools—yeshivot and Kollelim — associated with various ultra-Orthodox ideologies and practices. Cape Town’s yeshiva was established in 1994.

In the past, most South African Jews believed that their Jewish values and being “people of the book” engendered their group consciousness and cohesion. Many now recognize that these sensibilities, along with growing levels of observance, were at least partly the product of apartheid’s threats and constraints, including policies that actively and purposefully encouraged cultural exclusivity and separate group identities. Given that context, and their recognized vulnerability as members of a religiously defined minority, it is unsurprising that Jews historically engaged in relatively little national political dissent.

As the 2019 survey and selected interviews indicate, considerable diversity exists within the community, resulting in part from post-Holocaust consciousness as well as increased global antisemitism and anti-Zionism. Since South Africa’s democratization brought an embrace of diversity in all spheres, Jews have increasingly expressed their internal differences more openly—mainly within the community but occasionally in the broader public domain as well. As elsewhere in the Jewish world, generation is a key variable. Younger members are finding more positions on the continua of affiliation, participation, religious observance, and social and political conformity than did their parents and grandparents. In short, as South African society “normalizes,” South African Jewry is also normalizing, becoming more like other diaspora Jewish communities.

Women as Community Leaders

South African society is generally very patriarchal, which affects the leadership of all the country’s religions. At present there are just two female rabbis serving the Progressive/Reform movement: Rabbi Julia Margolis has led a congregation in Johannesburg since 2009, and Rabbi Emma Gottlieb has led in Cape Town since 2018.

Nevertheless, Jewish women have always played prominent roles in organizations and domains that supported communal life, and that tradition thrives today. For the early East European immigrants, supporting their families and fashioning a cohesive communal structure were priorities. While congregations were established throughout the country and Jewish organizations catering for diverse interests and needs proliferated, women involved themselves in “Ladies’ Guilds” attached to most congregations. Particularly in smaller rural communities, their activities often extended beyond synagogue matters. However, women seldom served on the main synagogue committees. Today, more women serve on synagogue committees, particularly in Progressive/Reform synagogues, and in keeping with the non-sexism incorporated into South Africa’as 1996 Constitution and Bill of Rights, more women are accepted as leaders in all Jewish communal structures.

Women and Jewish Welfare Organizations

Early community members were also active in welfare societies to help new arrivals and look after orphans (and later, the aged and widows), as well as in hevrot kaddisha (burial societies), Bikkur Holim societies to care for the sick, and soup kitchens. Today, women hold executive, professional, and administrative positions in such welfare organizations.

As of the 2020s, Jewish Care Cape brings together seven member organizations that deliver social services to Jews in the Western Cape. Two of the seven lay committee chairs and six of the executive directors are women. Jewish Community Services (JCS) is the oldest member organization and its history demonstrates the close association of women and welfare. The Philanthropic Society of the Cape of Good Hope was established in 1859 as an adjunct to the Cape Town Hebrew Congregation, the country’s first synagogue, popularly known as the Gardens Shul. In 1895 Reverend Bender created The Jewish Ladies Association, and the two organizations merged in 1921 to become the Cape Jewish Board of Guardians, which became JCS in 1998.While women were central to its provision of comprehensive aid and support to all Jews in the Cape, its first woman executive director was finally appointed in 2018.

Established in 1888, the Chevra Kadisha is Johannesburg’s oldest Jewish organization and has cared for the welfare and burial needs of the community ever since. “The Chev” manages several Homes and offers wide-ranging services. Today, four of its seven management committee members are women, as are three of its five care managers. However, only two of its eight-member board of governors are women: Rayanne Jacobson, expert in finance, and Brenda Lasersohn, a psychologist who has supervised and trained the organization’s social services personnel since the 1980s.

Having identified a rising incidence of sexual and other forms of abuse within the Jewish community and the community’s reluctance to acknowledge it, Wendy Hendler, (Yiddish) Rabbi's wife; title for a learned or respected woman.rebbetzin and life coach, and Rozanne Sack established Koleinu South Africa in Johannesburg in 2012. Koleinu provides an anonymous helpline for abuse victims, works closely with Jewish and non-Jewish organizations and professional experts, and educates widely on this issue.

Non-Jewish Welfare Organizations

Jewish women have also initiated welfare organizations that reach beyond the Jewish community. The few mentioned below focus on women’s accomplishments after 1990.

Ann Harris, a London solicitor, came to Johannesburg in 1987 with her husband, Cyril Harris, then newly appointed Chief Rabbi of South Africa. After working in the University of the Witwatersrand’s Law Clinic, she founded Afrika Tikkun in 1994 with her husband and three other Jewish men. Its widely admired Cradle-to-Career (C2C) approach aims to uplift young under-privileged South Africans while addressing their health and social needs. Harris contributes to many communal activities and was elected to the South African Board of Deputies (Cape Council) in 2020.

Driven by the desperation of multitudes of disadvantaged South Africans, Helen Lieberman (b. 1941) began her philanthropic work in 1963 and founded Ikamva Labantu in 1992. Today one of the largest NGOs in the country, Ikamva offers programs and centers that equip people with skills to improve their own situations. Most of its volunteers, specialist staff, and program managers live in the communities they serve. In 2017, among numerous awards, Lieberman was awarded the Officier de la Légion d’Honneur (National Order of the Legion of Honor), France’s highest honor for a foreign citizen, given “in recognition of her lifelong commitment to the eradication of poverty, injustice and human misery.”

Noting the number and desperation of abused women, and their ignorance about supportive resources, Ikamva Labantu social worker, remedial teacher, and Lifeline counselor Rolene Miller (b. 1938) personally funded and established Mosaic Training Services and Healing Centre in 1993. By 1994 the Centre was training women in social work skills and had developed a Court Support Desk to assist domestic violence complainants. Following requests to implement its court-support model more widely, the Centre extended it to four provinces, reaching over 100,000 people annually.

The Angel Network, initiated in 2015 by Glynne Wolman, Lindi Katzoff, Hayley Glasser, and Beverley Smith, operates entirely through social media and provides a portal to assist established welfare organizations. By 2020 its network facilitated and mobilized support for fifty NGOs, schools, creches, outreach centers, safe havens, orphanages, and the homeless nationwide, reaching about 40,000 people. During COVID-19, it extended assistance to more than 90 organizations, helping to provide food and services to more than 100 000 people.

Cadena SA was established in Johannesburg in 2018 under founding director Leanne Gersun Mendelow, to provide humanitarian aid and relief in emergencies and disasters. Responding in 2019 to the devastation of Cyclone Idai, Cadena supplied five-year water filters to some 26, 000 people, as well as hygiene kits and “dignity kits” (underwear and reusable menstrual pads) to schoolgirls. In 2020 Cadena also made available Covid 19-related aid and information pamphlets and videos, recorded in three local African languages.

Women in the Zionist Movement

South African Jewish women have always been very active in the Zionist movement, conducting practical work in education, fundraising, and organization. However not until 1928 did a leading woman Zionist, Katie Gluckmann, become an executive in the South African Zionist Federation.

The Bnoth Zion Association (Daughters of Zion), an organization whose membership grew from 60 to 160 in its first two months in Cape Town in 1901, began as an affiliate of the all-male Dorshei Zion. The BZA took responsibility for distributing Jewish National Fund “blue boxes” (Lit. "righteousness" or "justice." Charityzedakah boxes to raise funds for the Zionist enterprise), contributed to the newly formed WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization) in Palestine, initiated Hebrew classes for girls, and started the first Hebrew nursery school—all with its funds controlled by men. However, by 1930, the year white South African women were enfranchised, BZA finally took control over the money it raised and gained representation on Dorshei Zion.

In 1932 the Women’s Zionist Organization (WZO) of South Africa was formed. By 1967 its membership was 17,000, and by far the most active South African Zionist entity. In addition to fundraising for various Zionist projects, all branches offered members wide-ranging educational and cultural programs. In 1998 the WZO became WIZO South Africa, and in 2004 BZA become BZA/WIZO. More recently, and particularly in light of COVID-19, BZA/WIZO has extended its focus to help local institutions.

Whereas these women’s Zionist organizations have always been headed by women, the umbrella national South African Zionist Federation (SAZF) has never been chaired by a woman. However, Dr. Deborah Sagorsky (1963-1966), Myra Osrin (1984-1988), and Moonyeen Castle (2008-2010) have chaired the SAZF’s Cape Council. The current chair is Esta Levitas, and five of seven Council management committee members are women.

Focusing beyond the Jewish Community

Some women and organizations have chosen to direct their energies and activities beyond the community while still associating their activities with the label “Jewish.” Foremost among these is the Union of Jewish Women (UJW), founded by Toni Saphra (1877–1967) in 1931 as a national secular organization for Jewish women. A social worker, Saphra had been a member of the Jüdischer Frauenbund in Germany before emigrating to South Africa in 1900. Feodora Clouts (1899 - 1996), was a Jewish communal worker, Zionist activist, early feminist, and energetic advocate for Jewish and general education. Clouts shared Saphra’s dream of combining Jewish with civic and interdenominational activities, and they co-founded the Union’s Cape Town branch in 1932. Clouts studied social work at the University of Cape Town, was elected head woman student in 1919, and worked at Highlands House, a Jewish home for the aged. Acutely aware of the great inequalities in South Africa, particularly regarding education, she served for ten years as an elected member of the Cape School Board.

The UJW works closely with non-Jewish women’s organizations and has been at the forefront of countless major developments and outreach programs for the poor—including the early establishment of pre-schools in disadvantaged communities. Like WIZO, the Union also conducts extensive educational and cultural programs for its members. The UJW is affiliated with the International Council of Jewish Women (ICJW), which has representation on various United Nations committees. Lynne Raphaely, President of UJW South Africa, serves on the ICJW.

Mensch, founded in 2014 by its executive director Gina Flash brings together a network of about 80 social enterprises, many headed by women, gathering together Jews already working for the benefit of primarily poor and vulnerable non-Jewish communities. Ann Harris is a non-executive director, and six of eight board members, including Helen Lieberman, are women. Mensch offers capacity-building training, networking opportunities, mentorship, and collaboration, to help create a just, diverse and equal future for all in South Africa, within an organization motivated by Jewish values.

Neither the UJW nor WIZO espouses an overtly feminist philosophy. In the earlier period, Jewish women actively involved with feminism thus tended to be uninvolved with Jewish organizations, while women working for and with Jewish organizations did not, with individual exceptions, join “women’s movement” organizations. Young women who encountered feminism at university, and even those active in their teens in Jewish youth or student movements, were thus often not attracted to Jewish women’s organizations. However, after Mandela’s release in 1990 and during the negotiations towards apartheid’s demise, this situation began to change. Many women’s organizations, including Jewish ones, insisted on women’s liberation simultaneously with political liberation. Today, women hold prominent positions in these organizations, as well as in broader social and political arenas. With greater diversity within the Jewish community, strong young women who in the past might have distanced themselves from Jewish organizations now successfully combine their Jewishness with more general interests and activities.

In the past, volunteering in communal organizations was facilitated by the availability of affordable domestic labor, freeing Jewish women to be an important resource for communal activities. A significant number of them were members of more than one Jewish women’s organization, at least until the late 1970s, which resulted in valuable cross-fertilization of ideas and inter-organizational co-operation. As women have increasingly joined the workforce however, membership in all voluntary women’s organizations has declined, as has employment of full-time, live-in domestic workers.

Many Jewish women have combined engagement in social action to alleviate the plight of South Africa’s underprivileged with work for the Jewish community, often in leadership positions. Among the more prominent are Sheila Aronstam (b. 1926), honored for her welfare efforts in both the wider community and Jewish organizations; Selma Browde, [link to new entry on Browde] (b. 1926), a medical practitioner who served on the Johannesburg City Council and the Transvaal Provincial Council; Phyllis Lewsen (1916-2001), noted historian and passionate liberal; and Ina Perlman [link to new entry on Perlman](1926 - 2012), former director of Operation Hunger, whose feeding programs reached two million people.

With her husband Elliot, Myra Osrin (b. 1939) was influential in almost every aspect of Cape Town’s Jewish life. Her first formal position was as BZA/WIZO chair and then Western Province Zionist Council chair. In 1984 she initiated the monthly Cape Jewish Chronicle, always edited by women. She brought the Anne Frank in the World exhibition to Cape Town, providing a springboard for establishing the Cape Town Holocaust Memorial Council, which oversaw publication, in 1995, of In Sacred Memory: Recollections of the Holocaust by survivors living in Cape Town, edited by Gwynne Schrire. In 1999, Osrin founded and was first director of Cape Town’s Holocaust and Genocide Centre, stimulating a similar center in Durban led by Mary Kluk, who is also national president of the SAJBD, vice-president (South Africa) of the World Jewish Congress, and chair of the African and Australian Jewish Congress. Another center in Johannesburg is led by Tali Nates, a historian who has published widely and lectured internationally on Holocaust education, genocide prevention, reconciliation, and human rights. Osrin also established the Eliot Osrin Leadership Institute to ensure future good governance for the Cape Town community.

Marlene Silbert (b. 1934) applied her life-long commitment to human rights and Jewish heritage to activism with the civil and human rights monitoring group the Black Sash and the then (opposition) Progressive Party, and to education as a teacher at Herzlia High School in Cape Town, founding director of education at the Cape Town Holocaust and Genocide Center, and later as national education director for the South African Holocaust and Genocide Foundation. She developed a variety of quality educational programs and materials that are used in all three Holocaust and Genocide Centres. Silbert also founded the Interfaith Intercultural Schools Program, whose workshops focus on building relationships based on humanity, equality, social justice, peace, reconciliation and respect for the dignity of difference.

In 1995, one year after South Africa’s first democratic elections, Marlene Bethlehem, became the first woman to chair the then 92-year-old SAJBD, having previously chaired several Johannesburg-based Jewish organizations. As the national SAJBD’s chair (1995-1999) and as President (1999-2003), she represented South African Jewry nationally and internationally to Jewish and non-Jewish organizations. An advocate for human rights and equality, Bethlehem had strong bonds with President Nelson Mandela, accompanying him on his visit to Jerusalem. She had a similar relationship with Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, who appointed her deputy chair of the South African Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural and Linguistic Communities in 2004. Bethlehem also chaired the committee for the disbursement of the Swiss Banks’ Humanitarian Fund for Needy Holocaust Survivors and was the first South African elected vice-president of the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture (MFJC) in New York. She later served two terms as MFJC president, retiring in 2020. Her many awards include the Mendel Kaplan and Eric Samson Community Service Award presented by SAJBD president Mary Kluk.

Having been vice-chair of the SAJBD’s Gauteng Council and an elected SAJBD member, Wendy Kahn became the SAJBD’s first woman national director in 2006. Recognized in 2018 by the Jerusalem Post as one of the world’s fifty most influential Jews, Kahn has spoken out against genocide, xenophobia and the abuse of women and conducted campaigns encouraging Jews to participate in local democratic processes.

One hundred years after the establishment of the original Cape Board, in 2004 Moonyeen Castle became the first woman to chair the Cape Board of Deputies, followed by Li Boiskin in 2008. Vivienne Anstey and Adrienne Jacobson were each appointed vice-chair. Alison Katzeff was appointed as the first woman chair of the United Jewish Campaign, fund-raising arm of the Cape Town community, and has held that position since 2014.

Jewish Women in the Political Arena

Despite their upward mobility through the twentieth century, South African Jews have never constituted a significant political bloc. Their small number, the constituency-based parliament from 1910 to 1994, and a political system dominated by parties representing Afrikaans and English interests, limited their access to power. Yet their involvement in politics, especially opposition politics (liberal and/or left-leaning), has always been disproportionate to their number. Sonja Schlesin (1888 – 1956), best known as secretary in Gandhi’s law practice beginning in 1903, worked tirelessly for the Satyagraha campaign of nonviolent resistance and for the Transvaal Indian Women’s Association (TIWA). Bertha Solomon was a liberal parliamentarian and noted advocate on behalf of the underdog and Ray Alexander a communist and indefatigable trade unionist. Ellen Hellmann was a social anthropologist, authoritative liberal critic, and president of the Institute of Race Relations 1954–1955, Beulah Rollnick (1926-2020) a tireless worker with the Black Sash and later the Legal Resources Centre, and Audrey Coleman (b. 1933) a Black Sash activist and co-founder of the Detainees Parent Support Committee. Ruth First was murdered as a direct consequence of her willingness to confront the apartheid state, and Helen Suzman gained international recognition as a champion of the oppressed.

Between 1910 and 1994, many Jews—men and women—noted for their (radical) political activism were, in Isaac Deutscher’s term, “non-Jewish Jews.”Several leftist Jewish women born in eastern Europe or raised in communist homes—for example, Esther Barsel (1924-2008), Ray Harmel (1905–1998) [link to new entry on Ray Harmel-, Hilda Bernstein (1915-2006), and Pauline Podbrey (1922-2009)—were severely harassed by the security police, detained without trial, jailed, and/or banned for their political activities. Some felt their politics had roots in Jewish ethics or morality and some, like Esther Barsel, had been members of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, a socialist Zionist youth movement. All rejected the religious aspect of their Jewishness and felt alienated by and from the broader Jewish community. Some, like Podbrey, who had identified strongly as a Jew as a young girl in Lithuania, later saw themselves more as cultural than religious Jews and participated in Jewish community-sponsored public debates on anti-Zionism and antisemitism.

Gill Marcus, born in 1949 to communist parents, was an active worker for the African National Congress beginning in 1969, when she lived in London. Returning to South Africa in 1990, she was deputy finance minister in the first democratic government and deputy governor (1999-2004) and then governor (2009-2014) of the South African Reserve Bank. Marcus served on the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into allegations of impropriety by the Public Investment Corporation. In August 2020 she was a panelist in an SA Jewish Report webinar titled “Women of Substance.“

Although many public Jewish figures, particularly radical anti-apartheid activists, have had only tenuous Jewish identities, a few Jewishly identified women have served in senior positions in post-1994 administrations. Lisa Seftel (b. 1959), organizing secretary of JODAC (Johannesburg Democratic Action Committee) in the 1980s, has held various positions in local, provincial, and national government over several decades; in 2020 she was appointed the first female executive director of the National Economic & Development Labour Council (Nedlac). Lael Bethlehem (b. 1967), an urban development expert, has worked in the private corporate sector and held multiple senior positions in national and local government, including a five-year period as CEO of the Johannesburg Development Agency. Labor lawyer Tanya Cohen, having been director of the Retail Association, was appointed chair of the governing body of the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) in 2010. In 2016 she was appointed CEO of Business Unity South Africa (BUSA), organized business’s apex institution.

Contributions to specific social sectors

Jewish women have also contributed to the academy, the economy, and the arts. The SA Jewish Report began publishing annual “Jewish Achiever Award” winners in 1999 and later included the names of nominees. Relatively few women appear before 2015, when the Europcar Jewish Women in Leadership award was launched.

The Academy

As of 2019, 56% of Jewish women (who constitute 53% of the Jewish population) had achieved a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with 34% in 1998 and 24% in 1991. In earlier generations, the majority of Jewish women pursued careers in social work, librarianship, or teaching, several heading Jewish schools. Since the 1980s, women’s qualifications and careers have diversified considerably, with concentrations in medicine, law, psychology, and finance and increasing numbers in other sciences.

Some Jewish women have focused specifically on Jewish topics in their research and publications. Edna Bradlow (1924-2020) taught in the Department of History at the University of Cape Town and published widely (sometimes with her husband Frank) on well-known South African personalities and various Jewish topics, including Jewish immigration, women, and antisemitism. Veronica Belling, now research associate at the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Cape Town after three decades as the Centre’s librarian, has published several communal histories, translations from Yiddish of two early writers, and the invaluable Bibliography of South African Jewry (1997).

Jocelyn Hellig (1939 – 2008) taught in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand. In addition to her extensive academic publications, she served on the editorial board of Jewish Affairs and wrote for Jewish and general media. Extremely active in Jewish communal life in Johannesburg, she served on the Gauteng Council of the SAJBD for several decades and as vice-chair of the national Board. Valued for her expertise on antisemitism, the Holocaust, South African Jewry, the Middle East, and world religions, Hellig was much in demand at Jewish communal events and on radio and television.

Marcia Leveson had a distinguished career in the English Department at the University of the Witwatersrand, specializing in poetry and South African and nineteenth-century literature. She has edited anthologies of fiction and poetry, writes poetry and short stories, and, among other works, is the author of People of the Book: Images of the Jew in South African English Fiction, 1880-1992 (1999). She has served as the President of the English Academy of South Afric, and serves on the editorial board of Jewish Affairs.

Azila Talit Reisenberger (b. 1952) taught in the Hebrew Department at the University of Cape Town, heading the Hebrew section when the university formed its School of Languages. In addition to academic publications, she has published several volumes of poetry in Hebrew and English, short stories, plays, and a novel. Her work has appeared in Israel, South Africa, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany. In South Africa, which has eleven official languages, Reisenberger is known for her efforts to build bridges between languages. In 2005 she was elected president of the International Minority Literature and Cultures Association (IMLACA). A champion of women’s rights and gender equality, she is a registered Marriage Officer and Civil Union officiant and since 1989 has served as acting Rabbi of Temple Hillel, a progressive synagogue in East London, South Africa.

Many other Jewish women have been prominent in non-Jewish academic fields. Jill Adler (b. 1951) holds a SARChI (South African Research Chairs Initiative) chair in mathematics education at the University of the Witwatersrand and is president of the International Commission on Mathematical Instruction. Building on her research in multi-lingual classrooms and teacher professional development, Adler has initiated several large-scale teacher development projects and has received numerous awards.

In 1995, leading development expert Ann Bernstein, founded the Centre for Development and Enterprise, an independent research and advocacy organization, focusing on critical national development issues. Bernstein serves on several Boards, has been awarded prestigious international Fellowships, and has participated in seminal development initiatives in South Africa and internationally. Her 2010 book, The Case for Business in Developing Economies, was awarded the Sir Antony Fisher Memorial Prize in 2012, and Bernstein received the University of Johannesburg’s Ellen Kuzwayo award in 2019.

Economics, sociology, computer science, and mathematics expert Deborah Budlender (b. 1954) has conducted research, provided analyses and training, and designed projects and programs in multiple fields. Her early work with the Community Agency for Social Enquiry (CASE) has remained central to all her subsequent work. Her innovative ideas on gender-responsive and pro-poor budgeting have led to her involvement with various government departments in South Africa, international agencies such as UNESCO and other UN departments, and agencies in African, Latin American, European, and Commonwealth countries. While her gender-related work has remained a key focus, she has contributed to policy development in labor, education, economics, and poverty and organizational development and evaluation practice.

Tammy Cohen teaches Labour Law, Advanced Labour Law, and Employment Discrimination Law at the School of Law, University of Kwazulu-Natal. She received the Research Productivity Award in 2015. She is an Attorney of the High Court, a member of the South African Society on Labour Law (SASLAW), and an organizer of the Annual Labour Law Conference.

In 2004 Edna Freinkel (b. 1932), founder of the Readucate Trust, received the South African Presidential Award of the Order of Baobab for lifelong dedication to the development of specialized learning methods for the learning impaired. In 2010 she received the UNISA (University of South Africa) Outstanding Educator Award and in 2019 the Jewish Achiever Europcar Women in Leadership Award.

Head of the School of Management Studies at the University of Cape Town, Suki Goodman (b. 1972) received the 2017 Presidential Merit Award for Academic Excellence from the Society for Industrial & Organisational Psychology of South Africa (SIOPSA). In 2019 she received the Vice-Chancellor’s Transformation Award for dedication to institutional transformation in industrial and organizational psychology.

Judge Carole Lewis (b. 1953) was head of the University of the Witwatersrand Law School beginning in 1989 and dean of the law faculty from 1993 to 1998. She was also editor of the Annual Survey of South African Law and the South African Law Journal. She served as judge in the Johannesburg and Pretoria High Courts before being elected to the Supreme Court of Appeal in 2003. Lewis was awarded a Gold Medal in 2017 for her rich contribution to the life of the university while on its academic staff and her service to the institution during her subsequent judicial career.

Bonita Meyersfeld, director of the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (2012-2017), University of the Witwatersrand, is Chair of the Board of Lawyers against Abuse, which she founded in 2011. She has worked as the gender consultant to New York’s International Centre for Transitional Justice, is an editor of the South African Journal on Human Rights and non-executive director of the Centre for Environmental Rights and serves on the board of NPO Sonke Gender Justice. She received the 2018 Jewish Achiever Europcar Women in Leadership Award and in 2019 was made a Knight of the National Order of Merit by the French president for her work on human-rights and gender-based violence.

Industrial/organizational psychologist Karen Milner teaches in the School of Human & Community Development at the University of the Witwatersrand. She has published extensively in the fields of employee well-being, societal innovation and transformation, and diversity and inclusion. She chairs the Gauteng Council of the SAJBD and is deputy vice-chair of the national SAJBD.

Valerie Mizrahi (b. 1958) is director of the Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine (IDM) and the Molecular Mycobacteriology Research Unit of the South African Medical Research Council. Mizrahi’s research team at the University of Cape Town is internationally recognized for its work on the physiology and metabolism in mycobacterium tuberculosis, of relevance to TB drug discovery and drug resistance. A fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology and the Royal Society of South Africa, her major awards include the 2000 Unesco-L’Oréal Women in Science prize for Africa and the Middle East and the 2013 Christophe Mérieux Prize.

Sociologist/historian Deborah Posel (b. 1957) is a leading scholar of modern South Africa. She has written and published widely on aspects of South African politics and society during and beyond the apartheid era. Posel has also been an institution builder: in 2000, as the founding director of the University of the Witwatersrand Social and Economic Research (WISER) and in 2010 as the founding director of the Institute for Humanities in Africa (HUMA) at the University of Cape Town. Her wider research has often opened lines of inquiry into South African Jewish society and history, which she has presented at Limmud and other Jewish conferences, producing a close association with the Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research at the University of Cape Town. Since 2019, Posel has been research professor in sociology at the University of the Free State.

Amanda Weltman (b. 1979), a theoretical physicist at the University of Cape Town, holds a SARChI chair in physical cosmology. In addition to her scholarly work, Weltman promotes science education, especially for women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). She is a member of the Cape Town Science Centre Scientific Advisory Board and the South African Royal Society and on the executive of the South African Young Academy of Sciences.

Paediatric pulmonologist Heather Zar heads the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Cape Town and directs the Division of Paediatric Pulmonology at the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital. She established the hospital’s Research Centre for Child & Adolescent Health (REACH) in 2014 and a child health unit at the Medical Research Council in 2015. In 2014 she received the World Lung Health Award from the American Thoracic Society, given for the first time to someone from Africa and a childhood-health specialist. In 2018 she was named L’Oreal-UNESCO Women in Science Laureate for Africa and the Arab States, in recognition of her wide-ranging contributions to child health and helping to shape international policy.

Among the many Jewish women who have succeeded in business are Pam Herr (1949–2018), for many years a member of the Cape Town Chamber of Commerce, the Black Management Forum, and Business and Professional Women; Dionne Ellerine, chief executive of a major public company and non-executive director of various others; and Sharon Wapnick, chair of Octodec and a leading attorney.

Wendy Ackerman, entrepreneur, committed philanthropist, and co-founder and executive director of a leading retailer, has always promoted education among the underprivileged. She is a trustee of the Ackerman Family Educational Trust and of the Pick n Pay Bursary Fund and a trustee and board member of many other organizations. She has received numerous awards recognizing her contributions to South African society including Union of Jewish Women’s Woman of the Year (1982), Rotary International’s Paul Harris Fellowship (2000), and B’nai Brith Humanitarian Award (2018).

Suzanne Ackerman-Berman is Transformation Director and Chair of the Ackerman Pick n Pay Foundation and heads the Pick n Pay Small Business Incubator, which she founded to address apartheid-induced social and economic inequalities.

Wendy Appelbaum chairs an agricultural estate and was deputy chair and co-founder of the first women-controlled South African public company. Among her many directorships and trusteeships, she is a trustee of the Donald Gordon Foundation, Africa’s largest private charitable foundation. In 2006 she was listed among the Leading Women Entrepreneurs of the World, and in 2015 Forbes recognized her as Woman Businesswoman of the Year and Woman of the Year.

Reeva Forman began her career as a teen model and in 1974 established her very successful cosmetics manufacturing business. She won the South African Businesswoman of the Year award in 1983 and was the first woman in South Africa to be invited to join the Young Presidents Organisation. She became a member of Afrika Tikkun, served on the Gauteng SAJBD from 1998, joined the SAZF in 2002, and became an honorary president of the latter. In 1994, as chair of Temple Israel in Hillbrow, Johannesburg, Forman was instrumental in saving the building as a place of worship for the few remaining Jews in the area and creating an outreach center for the disadvantaged in the adjacent premises.

Joan Joffe (b. 1938), considered a legend of the Information Technology sector, launched Joffe Associates in 1977, the first organization to import, sell, and service the IBM PC. Thereafter she filled several roles at Vodacom, including chairing the Vodacom Foundation. She is a founding member of the broad-based women’s empowerment group Nozala Investments, has served on the boards of several non-profit organizations, and consults to the local ICT sector and several offshore technology companies. Joffe received the 2004 Fellowship Award from the Computer Society of South Africa and is a former Businesswoman of the Year and a recipient of the University of the Witwatersrand University Lifetime Award for Entrepreneurship.

Many Jewish women have excelled in journalism in South Africa, from Len Davis (1913-1977), who featured as “Aunty Len“ on a children’s radio program and was Cape Town’s correspondent for the Zionist Record and the London Jewish Chronicle for fourteen years, to Lindy Diamond (b. 1980), editor of the monthly Cape Jewish Chronicle and Peta Krost Maunder, editor of the widely read weekly SA Jewish Report.

Irma Chiat (1941-2020) was the first editor of the Cape Jewish Chronicle, from 1984 to 2010. She was followed by Tali Feinberg, who now writes for SA Jewish Report. Janine Lazarus was first editor of the Jewish Report, from 1998 to 1999, followed briefly by Suzanne Belling, then Vanessa Valkin from 2014 to 2016.

Suzanne Belling (1947-2020), author of four books, has held multiple editorial and communal positions in both Johannesburg and Cape Town: 1970s Cape Town correspondent and regional editor of the former SA Jewish Times, becoming editor in 1984; South Africa correspondent for the London Jewish Chronicle and JTA; founding editor of the former Johannesburg Jewish Voice; part-time senior journalist for SA Jewish Report; Executive Director of UJW and SA Friends of Ben Gurion University in the late 1980s and of Cape SAJBD from 2001 to 2007, and public relations officer for Torah Academy School 2008 – 2019.

Independent scholar and writer Claudia Braude has published on a variety of South African Jewish topics. She consulted for the South African Human Rights Commission on racism in the media (1999-2000), edited Contemporary Jewish Writing in South Africa: An Anthology (2001), and in 2011 created the Litvish Legacy Foundation to explore the Lithuanian Jewish presence in South Africa.

Over several decades, Raphaely became one of the most influential names in South African publishing. Jane Raphaely (b. 1937) launched Fair Lady magazine in the 1960s and was followed into the industry by daughters Julia and Vanessa. Associated Media Publishing, with Julia as CEO, produced several popular and respected local and international titles for many years but was forced to cease operating in 2020 due to the impact of Covid 19.

During her journalism career, Carolyn Raphaely has held a variety of journalistic and editorial positions and covered a wide range of topics, from design and décor to finance, the environment, and human rights issues. She is senior journalist at The University of the Witwatersrand Justice Project, which investigates human rights abuses and miscarriages of justice related to the criminal justice system.

Multi-media journalist, editor, producer and publisher Nechama Brodie has authored several critically acclaimed non-fiction works and two novels and co-authored two memoirs. She lectures in the School of Journalism and Media Studies, University of the Witwatersrand. Multi award-winning journalist Mandy Wiener specializes in investigative reporting and legal matters and achieved “book of the year” for publications in 2011 and 2013. Lisa Chait, a well-known documentary and online producer, founded a unique family history/archive project and is co-producer, writer & presenter of an award-winning TV and online series.

Novelist Rose Zwi (1928-2018) and poet Helen Segal (b. 1929) are among those whose works engage directly with the substance of Jewishness. Other widely known writers include Afrikaans-language poet Olga Kirsch (1924-1997), Jillian Becker (b. 1932), and Shirley Eskapa (1934 - 2011), both fiction & non-fiction, and Gillian Slovo (b.1952), writer, journalist and film producer.

Novelists Sarah Gertrude Millin and Nobel Prize-winner Nadine Gordimer are well known in their fields both in and outside of South Africa.

Creative and Performing Arts

In South Africa Jewish women have made valuable contributions to the full range of cultural activities as producers, consumers, and sponsors. The following are a few of the many women active in the creative and performing arts.

In addition to acting and directing, Taubie Kushlick (1911–1991) made her name in theater through her forceful personality and her presentations of the songs of Jacques Brel. The unique style and irrepressible humor of Molly Seftel (b. 1930) are unforgettable, and Cecilia Sonnenberg (1912–2000) and Rene Ahrenson (1904–1990) developed an open-air venue for Shakespearean productions in 1949 that is still widely used today. Early in the twentieth century, when many Eastern Europeans immigrants ensured Yiddish theater’s popularity, actress and theatrical entrepreneur Sarah Sylvia (1890-1976) was a household name, while Chayala Rosenthal (1927–1979), a Holocaust survivor, re-invigorated Yiddish theater and song in the 1950s.

More recently, Aviva Pelham (b. 1948) is a renowned multi-genre singer and an active contributor to Jewish community events. and Beverley Chait (b. 1973) made a career in opera. Director/producer Phyllis Klotz (b. 1945) was among the first white artist to work with young people in black townships, using drama as a medium of potential empowerment. Hazel Feldman (b.1948), one of South Africa's best known theater producers and founder of Showtime Management, received the 2018 Jewish Achiever’s Art, Sport, Science, and Culture Award.

In the art world, Thelma Chiat (1918-2009) was best known for her pen-and-ink drawings. Naomi Jacobson (1925-2016) produced well-known sculptures of many prominent Southern African personalities, including a head of Nelson Mandela. Painters Aileen Lipkin (1933-1994), Eris Silke (b. 1947), Francine Greenblatt (b. 1951), and Claire Gavronsky and Rose Shakinovsky, collectively known as Rosenclaire, are all well known, as are many Jewish art critics, historians, and gallery-owners. Prominent among the latter was Esmé Berman (1929 – 2017), art historian, art critic, respected researcher and author.

Artist and author Terry Kurgan explores photography through a diverse body of multi-media artwork and writing. She has exhibited and published widely in South Africa and internationally and received numerous awards. In 2019 she won the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award for her third book Everyone Is Present: Essays On Photography, Memory And Family (2018).

Jewish women have also made their mark on the world of dance in South Africa. Phyllis Spira, Adele Blank (b. 1943), Mavis Becker (b. 1940), Sylvia Glasser (b. 1940), Sharon Friedman (b. 1946), Sonja Mayo (b. 1945), and Robyn Orlin (b. 1955) have each contributed both performance prowess and teaching skills across a wide variety of dance genres.

Recent and ongoing initiatives

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, women founded and/or led several new organizations that have changed South African Jewry’s social and intellectual landscape considerably. Vivienne Anstey, social worker and graduate of the Hornstein Program in Jewish Communal Service at Brandeis University, established Cape Town’s Midrasha Adult Education Institute in 2006, incorporating the well-known Florence Melton School of Adult Jewish Learning, which offers Hebrew University-designed programs. Despite reduced community numbers, the programs have not only survived but new ones have been introduced andadditional courses are constantly being developed and taught by local Midrasha faculty. Anstey also introduced Limmud to Cape Town in 2007. It has since spread to Johannesburg and Durban and proven extremely popular. Anstey has served several terms as vice-chair of the SABJD’s Cape Council and heads the Eliot Osrin Leadership Institute, established in 2017.

Orthodox feminist Adina Roth studied clinical psychology and literature and Torah learning and established B’tocham Education for b’not mitzvah in 2007, now expanded to include b’nei mitzvah for boys and adults as well. Roth is a key figure in Limmud Johannesburg and has chaired Limmud SA for several years.

In 2008 a Jewish radio station, ChaiFM, commenced broadcasting in Johannesburg and via the Internet to South Africans abroad diaspora. Founder & CEO Kathy Kale won a Jewish Achiever Award in 2017. The station has an estimated 85,000 listeners daily and 15,000 in over 80 countries via the Internet.

In 2016, writers Joanne Jowell (b. 1974) and Cindy Moritz (b. 1971) helped to establish the now well-attended annual Jewish Literary Festival. Both are writers and co-directors and active in other areas of Jewish communal life, as are JLF team members Caryn Gootkin (b.1970) and Beryl Eichenberger. The festival takes place at the complex that houses the Cape Town Hebrew Congregation, the oldest synagogue in the country, the SA Jewish Museum, the Holocaust and Genocide Centre, Café Riteve and, most appropriately, the Jacob Gitlin Library, developed into a much-valued community asset by its dedicated librarians: Yvonne Verblun and Dr Ute ben Yosef in the past, and current head Jacqui Rodgers.

In 2011 physiotherapist Marilyn Bassin founded Boikanyo, a nonprofit that works with indigent children and their caregivers in poor townships in Gauteng, provides clothing and mathematics and life-skills to school children, assists shack-dwelling children with special needs, and in 2012 established a community/school vegetable garden that has been self-sustainable since 2017.

Moved to do something in 2014 for homeless people on the streets of Cape Town, Kerry Hoffman began serving soup and sandwiches out of her car. In 2017 she was joined by Caryn Gootkin, and Souper Troopers was registered as a nonprofit that, in collaboration with corporates and volunteers, including homeless individuals, organizes monthly social events that bring dignity and services to homeless people.

Nicole Mirkin (b. 1994) activist against gender-based violence, founded Fight Back SA in 2019 to teach self-defense to women in underprivileged areas, free of charge, using Israeli krav maga techniques.

Conclusion

Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, South Africans had acknowledged the serious socio-political and economic challenges facing the country in its third decade of constitutional democracy. These challenges, exacerbated by the pandemic, trouble the Jewish community no less than other citizens. In addition, the 2019 national Jewish population survey confirmed declining numbers, a rising proportion of elderly, and likely continued emigration. Those most likely to emigrate are talented and skilled young singles, childless young couples, and older wealthy people, often benefactors of the community. Communal leaders have recognized the need for strong lay, professional, and younger leadership, including women, and new organizations have emerged to ensure communal security and continuity. The new organizations reflect greater diversity within the community—of interests, opinions, and practices—and individuals show increased willingness to express disagreement or opposition more openly and honestly, including with regard to attitudes toward Israel.

The number and range of religious practices and norms in Johannesburg has grown increasingly over several decades but has not given rise to major tensions among Jews in the city, and most formal organizations affiliate to the umbrella bodies. Cape Town, too, offers more religious and other Jewish options than in the past.

One gender-related incident came close to splitting the community. At the 2016 Cape Town Yom HaShoah ceremony (a secular occasion), women were not permitted to sing on grounds of the prohibition known as Kol Isha, according to which men should not hear the voices of women. Two Jews (one male, one female), together with interfaith organization SACRED, the South African Centre for Religious Equality and Diversity, sued the Cape Board of Deputies in the Western Cape Equality Court on constitutional grounds, for unfair discrimination against women. Eventually settled out of court, the matter was divisive within the community. While multiple opinions were expressed (some traditional, some feminist), many individuals on all sides were distressed that an internal community dispute was being aired publicly.

Notwithstanding its challenges, the South African Jewish community is neither paralyzed nor polarized. Increased internal diversity has, rather, added new and attractive Jewish options of activities and engagements. Moreover, Jews have made massive individual, collective, and collaborative contributions to helping reduce both Jewish and non-Jewish suffering due to Covid 19. Women have been crucial in these endeavors. Under apartheid, Jewish women in welfare organizations had more dealings with and knowledge of both state structures and disadvantaged communities than any other sector of the organized Jewish community. That experience is invaluable and may partially account for the new women-initiated organizations that have emerged.

Jewish women have been central to the extraordinary vitality manifest in every area of community life, despite the diminishing numbers. They have continued and improved the services and care given to all community members and to under-privileged South Africans; they have established organizations, launched innovative projects, increased their Jewish learning and practice, taught others, introduced mass challah bakes, and created The new moon; the first day of the month; considered a minor holiday, especially for women.Rosh Hodesh groups and discussion and study groups around a wide variety of Jewish topics. And they have done so while working outside the home and/or taking responsibility for the well-being of family members.

Abrahams, Israel. The Birth of a Community. Cape Town: Cape Town Hebrew Congregation, 1955.

Arkin, Marcus, ed. South African Jewry: A Contemporary Survey. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Belling, Veronica. Bibliography of South African Jewry. Cape Town: Jewish Publications-South Africa, 1997.

Belling, Veronica. “Recovering the lives of South African Jewish women during the migration years c1880-1939.” PhD Diss., University of Cape Town, 2013.

Bruk, Shirley. Jews of the “New South Africa”: Attitudes, Beliefs and Behaviour Patterns: Religiosity. Occasional Report No. 1. Cape Town: Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research, 2003.

Dubb, Allie A. The Jewish Population of South Africa: The 1991 Sociodemographic Survey. Cape Town: Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research, 1994.

Gitlin, Marcia. The Vision Amazing: The Story of South African Zionism. Johannesburg: Menorah Book Club, 1950.

Jungbacke, Hazel. "Feodora Clouts: 'The Grand Old Lady of Cape Town Jewry.'" Jewish Affairs 76 (2020): 48-55.

Kalechofsky, Robert & Roberta Kalechofsky, eds. South African Jewish Voices. Marblehead, MA: Micah Publishers, 1982.

Kaplan, Mendel. Jewish Roots in the South African Economy. Cape Town: Struik, 1986.

Kosmin, Barry A., Jacqueline Goldberg, Milton Shain and Shirley Bruk. Jews of the “New South Africa”: Highlights of the 1998 National Survey of South African Jews. jpr/report. September 1999.

Mendelsohn, Richard, and Milton Shain, eds. The Jews in South Africa: An Illustrated History. Johannesburg & Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 2008.

Norwich, Rose. “Jewish Women in Early Johannesburg.” Jewish Affairs 48 (1993): 89–99.

Republic of South Africa. Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women: First South African Report. http://www.welfare.gov.za/reports/1997/cedaw1.htm.

Republic of South Africa: 2nd Report: Country Response to Questions and Concerns raised by CEDAW.

Saron, Gustav, and Louis Hotz, eds. The Jews in South Africa: A History. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1955.

Schrire, Gwynne. “Women and Welfare: Early Twentieth-Century Cape Town.” Jewish Affairs 48 (1993): 85–88.

Schrire, Gwynne. “For the Greater Good of Society: Five Remarkable Cape Town Women.” Jewish Affairs 73 (2018): 28-34.

Schrire, Gwynne. “The Cape SAJBD, the Silver Salver and Bertha’s Bill.” Jewish Affairs, 68 (2013): 15-17.

Shain, Milton. The Roots of Antisemitism in South Africa. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1994.

Shain, Milton, and Sally Frankental. “Accommodation, Activism and Apathy: Reflections on Jewish Political Behaviour During the Apartheid Era.” Jewish Affairs 52 (1997): 53–57.

Shain, Milton and Richard Mendelsohn, eds. Memories, Realities and Dreams: Aspects of the South African Jewish Experience. Johannesburg & Cape Town: Jonathan Ball, 2002.

Shimoni, Gideon. Jews and Zionism: The South African Experience 1910–1967. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Simoni, Gideon. Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa. Hanover and London: Brandeis University Press, 2003.

Suttner, Immanuel, ed. Cutting Through the Mountain. Interviews with South African Jewish Activists. London: Viking, 1997.

Widan, Bertha. “Women’s Role.” In Forty Years in Retrospect: The Story of the Western Province Zionist Council, edited by David Sherman, 31–36. Cape Town: Western Province Zionist Council, 1984.