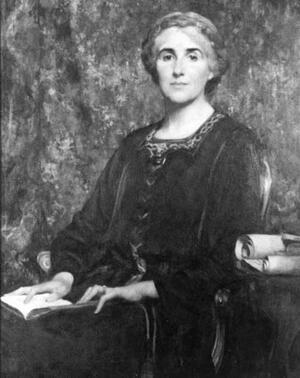

Nina Ruth Davis Salaman

Nina Salaman received an intensive Hebrew education and while still in her teens began publishing translations of medieval Hebrew poetry in the Anglo-Jewish press. After marrying Redcliffe Salaman and settling in Hertfordshire, she continued to pursue her interest in medieval poetry and became a well-regarded Hebraist, at a time when Jewish scholarship in Europe was a male preserve. In addition to her translations, she published historical and critical essays, book reviews, and an anthology of Jewish readings for children, as well as poetry of her own. She also became active in the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage and was particularly concerned with the Hebrew education of Jewish girls. Although she was not a radical feminist, her behavior was quietly subversive of traditional gender roles.

Nina Salaman was a well-regarded Hebraist, known especially for her translations of medieval Hebrew poetry, at a time when Jewish scholarship in Europe was a male preserve. In addition to her translations, she published historical and critical essays, book reviews, and an anthology of Jewish readings for children, as well as poetry of her own.

Early Life & Education

Nina Ruth Davis Salaman was born on July 15, 1877, in Derby in England’s industrial heartland, to Arthur and Louisa (Jonas) Davis. Her father’s family were precision instrument makers (telescopes, opera glasses, miners’ lamps) and had lived in England since the early nineteenth century. When she was six weeks old, the family moved to London, settling first in Kilburn and then later in Bayswater. Although not an observant Jew by birth (there were few Jews and no synagogue in Derby), Arthur Davis embraced Orthodoxy and, having mastered the Hebrew language, devoted his leisure and then retirement to Jewish scholarship. In 1892, he published a study of the neginot (cantillation marks) in the Masoretic text of the Bible, and in the next decade, working with Herbert Adler (1876-1940), a lawyer and nephew of Chief Rabbi Hermann Adler (1839-1911), prepared what became the standard British edition and translation of the mahzor (festival prayer book).

Arthur Davis transmitted his enthusiasm for Hebrew to his daughter Nina and, most unusually, gave her and her older sister, Elsie (1876-1933), an intensive Hebrew education, personally teaching them every day. While still in her teens, Nina began publishing translations of medieval Hebrew poetry in the Anglo-Jewish press. She also contributed translations to her father’s edition of the mahzor. Israel Zangwill (1864-1926), the best known Jewish writer in the English-speaking world at the time and, like her father, a member of the Kilburn Wanderers (the circle that formed around Solomon Schechter [1847-1915] in the 1880s), encouraged her and provided her with an introduction to Judge Mayer Sulzberger (1843-1923), a leading figure in the Jewish Publication Society of America, which published her collection Songs of Exile by Hebrew Poets in 1901.

Marriage & Family

On October 23, 1901, Nina married Redcliffe Nathan Salaman (1874-1955), a physician who had fallen in love with her four months earlier when she saw her sitting in the women’s balcony of the New West End Synagogue in London. After living in Berlin for several months, while Redcliffe completed advanced training in pathology, they returned to London, where he assumed the directorship of the Pathological Institute at the London Hospital. However, tuberculosis forced him to leave medicine in 1904, and after three months of recuperation in Switzerland, he and Nina settled in the country, in the village of Barley in Hertfordshire, about fourteen miles from Cambridge. Family money (ostrich feathers and London real estate) having relieved her husband of the need to earn a living, they lived comfortably with their six children (one of whom died in childhood) and numerous servants in a thirty-room country house. Nina Salaman continued to pursue her interest in medieval Hebrew poetry, travelling frequently to Cambridge to use the library. At the same time she supervised her children’s education, oversaw nannies, tutors, and servants, and, as the local squire’s wife, entertained the vicar, hosted garden parties, and helped the village poor. Despite Barley’s distance from London, she maintained a Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher home (a matter of greater concern to her than to her husband) and Sabbath observance. She took personal responsibility for the Hebrew education of her children until they left for boarding school, especially that of her eldest son, Myer, whom she hoped would become a rabbi.

Literary Work

Barley’s proximity to Cambridge brought Salaman into close contact with Israel Abrahams (1858-1925), reader in rabbinics at the university since 1902, and, like Zangwill and her father, one of the Kilburn Wanderers. She met with him frequently in Cambridge—he regarded her as his superior in reading medieval Hebrew poetry—and occasionally left her boys in his care. While she worked in the university library, he would give them Hebrew lessons and show them around the university’s museums. In 1916, the Jewish Publication Society of America invited her to translate poems of Judah Halevi (before 1075-1141) for its Schiff Library of Jewish Classics. She worked on the Halevi volume at the same time that her friend Israel Zangwill was preparing a volume of Solomon ibn Gabirol’s (c. 1020-c. 1057) religious poems for the same series and they frequently compared notes and critiqued each other’s work. She submitted the manuscript in 1922 but the book did not appear until late 1924, a few months before her death. It has remained in print continuously since then.

Women & Judaism

While wedded to Jewish tradition, Salaman was not a traditionalist when it came to the position of women. Like Zangwill and her sisters-in law Isabelle Salaman Davis and Jennie Salaman Cohen, she was active in the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage, which campaigned not only to win the vote for women but to improve the status of women in the Jewish community, including the right of women seat-holders to vote in synagogue elections. She was particularly concerned with the Hebrew education of Jewish girls, whom she believed held in their hands the destiny of the Jewish people. Because mothers spent more time with their children than did fathers, who were immersed in making a living, she believed it was the formers’ responsibility to instill in their children a knowledge of Hebrew—as she was doing at Barley. While this was a naïve and utopian solution to Jewish continuity, her insight that intensive immersion in Hebrew from an early age was an effective way to combat the hegemonic influence of English-language schooling was spot-on.

Although Salaman was not a radical feminist, her behavior was quietly subversive of traditional gender roles. Her lectures and publications, for example, shattered what had been a male monopoly on Jewish scholarship in Britain. Her most daring break with the gender regime of traditional Judaism occurred in 1919. On Friday evening, December 5, she became the first—and only—woman ever to preach in an Orthodox synagogue in Great Britain. She spoke on the weekly Torah portion (the story of Jacob’s wrestling with an angel) at the Cambridge Hebrew Congregation, a traditional synagogue but one independent of the authority of the chief rabbi. The event caused a stir, not in Cambridge, but elsewhere in Anglo-Jewry and even beyond. When asked whether Jewish law permitted women to speak from the pulpit, Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz (1872-1946) neatly sidestepped the issue. He ruled that since Salaman did not enter the pulpit until after the concluding prayer, she did not preach during the service and thus she did not preach in the synagogue, since at that moment the building was not being used for religious worship.

Nina Salaman’s thinking about Judaism is not easily categorized as either traditional/Orthodox or as progressive/Reform, at least as these terms are usually understood today. It is, however, very much in the tradition of Anglo-Jewish bibliocentricity, an approach to Judaism that privileged the Bible as a source of religious inspiration without abandoning centuries of rabbinic tradition. Following in her father’s footsteps, she emphasized the Bible as the primary source of divine wisdom and law and held that all its commandments were binding, unlike commandments rooted in rabbinic interpretations, which were not fully incumbent on modern Jews. But she was in no sense a biblical fundamentalist. She was well aware that critical scholarship had undermined the literal narrative of the Bible. To her, however, this was unimportant and beside the point. What mattered was not the literal meaning of the text but the grains of truth and beauty embedded in it.

Like her husband, Salaman was a passionate Jewish nationalist. In 1916, she published one of the first English translations of the Zionist anthem “Ha-Tikvah” and later wrote the marching song for the Judeans, the Jewish regiment that took part in the British conquest of Ottoman Palestine at the end of World War I. To mark the issuance of the Balfour Declaration (November 2, 1917), she and her husband planted a new orchard in the meadow of their Hertfordshire home, naming it “The Jerusalem Orchard.”

Nina Salaman died on February 22, 1925, her life cut tragically short by cancer. She was buried on February 25, The new moon; the first day of the month; considered a minor holiday, especially for women.Rosh Hodesh Adar, in the Salaman family plot at Willesden Cemetery in London. It is customary to omit the funeral sermon on rosh hodesh—except in the case of an eminent scholar. The chief rabbi, accordingly, delivered a eulogy at her funeral.

Selected Works

Davis, Nina. trans., Songs of Exile by Hebrew Poets. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1901.

The Voices of the Rivers. Cambridge: Bowes & Bowes, 1910.

“The Hebrew Poets as Historians,” Menorah Journal 5:5 (October 1919) and 6:1 (February 1920).

Ed., Apples & Honey: A Gift-Book for Jewish Boys and Girls. London: Heinemann, 1921.

“Ephraim Luzzatto (1729–1792),” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England 9 (1922): 85–102.

Songs of Many Days. London: Elkin Matthews Ltd, 1923.

Trans., Selected Poems of Jehudah Halevi, ed. Heinrich Brody. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1924.

Rahel Morpurgo and Contemporary Hebrew Poets in Italy. Sixth Arthur Davis Memorial Lecture. London: G. Allen & Unwin Limited, 1924.

Endelman, Todd M. “The Decline of the Anglo-Jewish Notable.” The European Legacy 4:6 (1999): 58–71.

Loewe, Herbert M. “Nina Salaman, 1877–1925.” Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England 11 (1928): 228–232.