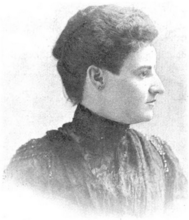

Flora Sophia Clementina Randegger -Friedenberg

Born in Italy in 1825, Flora Sophia Clementina Randegger-Friedenberg was a persistent educator and writer. She is best known for the publication of her Jerusalem journal, which shared her extraordinary experiences in a way that combined messianic hope and the enlightenment ideals of knowledge and progress. Flora began writing at a young age. After the death of her father, she began publishing her writing and soon moved to Jerusalem to pursue an educational project that would be part of the resurgence of the Jewish people. She ran and taught at a highly controversial girls’ school in Jerusalem, persisting through communal pushback and financial strain. She was described as an important, cultured, and intelligent woman.

Overview

“At last I have come to where my desire led! I have come to Jerusalem! But how, all alone, have I dared so much?!” With these words Flora Randegger opens her travel journal. A young teacher from Trieste, Italy, she reached the Holy Land in 1856, after an adventurous journey she had undertaken on her own. Figuring among a precious few accounts left by a Jewish woman of a stay in the Old Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv in nineteenth-century Jerusalem, her journal is also a record of a woman’s attempt to establish an educational project for Jews and especially for Jewish women in Palestine.

With its freshness and the wealth of observations on various aspects of local life, Randegger’s Jerusalem journal is by far the best among her various writings. She describes her extraordinary experience in detail, with a clever eye and a sharp sensitivity to shapes and colors, conveying the impact of Oriental customs and habits on a European woman. At the same time, the journal reveals the efforts of a Jewish soul attempting to join present and past, in a spirit that in peculiar ways combined messianic hope and the enlightenment ideals of knowledge and progress. Because it is a woman’s soul, it lends a specific tone to the journal’s effusions, where ideal impulse must confront the limitations that the age imposed on her gender.

Randegger had begun her journey guided by the feeling that Divine Providence was leading her forth, and as a way to honor the memory of her beloved father, whose death had prevented her from keeping the promise to travel together to Jerusalem to celebrate A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover.

During a time of illness that followed her father’s death, she had transformed from a Jewish woman of the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora—dreaming of Jerusalem as a remote and ideal destination—to a pioneering precursor of Zionism, determined to carry out her educational project as part of the resurgence of the Jewish people. This transformation had not come easily, as Randegger relates in the journal, where she describes struggling with herself, with the family, with physical debility, and the lack of financial means.

She had started out on her adventure to Palestine out of love for the Jews of The Land of IsraelErez Israel, aiming to apply there the knowledge she had already been popularizing in her native Trieste, a knowledge that, while preserving the ties with Judaism, also demonstrated the mixture of European culture and religious fervor that characterized her family.

Family

Flora’s father was the learned Rabbi Meir Randegger, born in 1780 in the German town of Worblingen in the Bodensee region. After moving to Trieste in the early 1800s, he married the daughter of the secretary of the Jewish community, a woman from the Galligo family. In Trieste, he taught secular subjects at the Lit. "study of Torah," but also the name for organizations that established religious schools, and later the specific school systems themselves, including the network of afternoon Hebrew schools in early 20th c. U.S.Talmud Torah school, tutored students in French and German, and was the rabbi at the Ashkenazi synagogue. Between 1832 and 1834, he acted as chief rabbi for the entire community. During his absence from Trieste between 1837 and 1848 he performed the duties of rabbi in other towns. He died in 1853, after returning to Trieste.

Among Meir Randegger’s students was the celebrated Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal, 1800–1865), who was devoted to his teacher and shared his love for Hebrew and Judaism, as well as a great familiarity with European culture. They both contributed to Jewish Enlightenment; European movement during the 1770sHaskalah (Jewish enlightenment) publications. Meir Randegger also taught his own son Joseph Aaron (who became Shadal’s first and much beloved pupil) and his daughters, Flora and Teresa, in this spirit.

Early Life

Born in Trieste on March 4, 1824, Flora followed her father to Vienna in 1847 and there started writing the journal she was to keep for many years and that would become the precious testimony of her Jerusalem mission. Before traveling to the Holy Land, she translated the Passover The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah into Italian. Her father had the translation published in Vienna (but with no mention of her name on the cover), where it appeared in two editions in 1851 and 1853. Rachel Morpurgo, the first modern Jewish woman poet and Shadal’s cousin, quoted Flora Randegger’s translation in an 1851 poem composed on Meir Randegger’s birthday, which was published in 1853 in Kokhvei Yizhak (Isaac’s Stars) and again in 1890, in a posthumous collection of Morpurgo’s works, Ugav Rahel (Rachel’s Harp). After earning her high school diploma in education in Trieste, Flora Randegger taught, together with her father and her sister Teresa, at a local private school for girls they had opened in 1848. In 1853 she was granted a permanent teaching position in the girls’ section of the school that served the Triestine Jewish community. However, she resigned from the post in 1854 due to poor health.

Publications

After her father’s death, Flora published two poems honoring his memory in an 1853 issue of the periodical L’Educatore Israelita (The Jewish Educator), published in Vercelli, Italy. In 1854 and 1855 the same periodical published two of her moral commentaries on the Psalms and, also in 1855, announced the publication of Strenna Israelitica (A Jewish Holiday Gift), a volume Flora had compiled, with contributions from herself, her brother Joseph Aaron, her sister Teresa, and others, including Shadal.

In 1857 L’Educatore Israelita published two abstracts from her journal, under the title “Il diario di una donna israelita in Gerusalemme” (The Journal of a Jewish Woman in Jerusalem).

In 1864, Randegger published in Trieste a translation of the book of Joshua, with the title Prima traduzione israelitica italiana del libro di Giosué (First Italian Translation of the Book of Joshua by a Jewish Author).

In 1869 she published, also in Trieste, Un po’ di tutto. Seconda strenna Israelitica (A Bit of Everything: A Second Jewish Holiday Gift). The volume included the journal of her two visits to Jerusalem, some commentaries on the Psalms (already published, in part, in L’Educatore Israelita), the short story “Giannetta” and some poems.

The Palestine travel journal devotes the first two of its three parts to Randegger’s first trip and her stay in Jerusalem from 1856 to 1858, while the third part records the second journey to Jerusalem and her stay in the city from 1864 to1866. Some sections of the journal relating to the first visit, which L’Educatore Israelita had published in 1857, do not appear in Un po’ di tutto. Seconda strenna Israelitica (hereinafter, Un po’ di tutto).

Themes and Outlook

Her upbringing in the Triestine cultural atmosphere, which combined reverence for Jewish faith and culture with an attachment to Italian culture, was among the elements that contributed to Randegger’s outlook. Also noteworthy is the influence of the Holy Land emissaries seeking help for Palestine Jews, whose presence in Trieste had been conspicuous since the late eighteenth century. In the following century, Rabbi Abraham Eliezer Halevi of Jerusalem, who served as chief rabbi of the Triestine community from 1801 to 1825, had fostered strong ties between this community and their brethren who, despite the great hardship and poverty they faced there, had elected to move to the Holy Land.

In the introduction to Un po’ di tutto, Randegger sets out her purpose for publishing the Jerusalem journal. She meant to share her impressions of the Holy Land with Triestine Jews who had been unable to visit it, hoping to instill in her readers at least part of the “national fervor” that burned in her soul and a desire for Israel’s “renaissance.” Randegger describes this “renaissance” as the recognition of the religious duties incumbent on the Jewish people in their role as a “sacerdotal nation.” Through this recognition she meant to awaken “tepid” Jews who had allowed themselves to be seduced by the comforts of the Diaspora and the attractions of mundane life.

Coupling loyalty to the “sacerdotal” nature of Israel with the enlightenment ideal of education and setting it against the background of the “progress” of the times, Randegger formulated a messianic concept that, while remaining faithful to Jewish specificity, echoed the motifs of the sector of Triestine Jewry that was familiar with European secular culture and the ideals of historical progress. Aware that, as a woman, she was subject to misinterpretation, she managed to convey to the reader the sense of a program while, however, leaving it only in terms of an exhortation to keep faith with Judaism and help Jews living in the Holy Land.

Randegger’s Girls’ School

In the journal, Randegger tells of a school for girls functioning in Jerusalem since c. 1855. Initially opposed by local rabbis, who had threatened it with a Ban; excommunication (generally applied by rabbinic authorities for disciplinary purposes).herem (ban), the school was eventually allowed to continue operating. It served about one hundred girls, from the Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardi and Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi communities, with two teachers for the Sephardi girls and two for the Ashkenazi. Besides knitting and sewing, the students learned to read Hebrew. No other subjects were taught because, as Randegger noted, the teachers themselves did not know much more. As she relates in the journal, local Jews, and particularly the Ashkenazim, viewed education for girls with suspicion. Nonetheless, several families (evidently mostly Sephardi) wanted their children to learn a European language. Since they already spoke Ladino, their preference was for Italian because of its similarity to Ladino. After voluntarily tutoring six girls and three boys in the first few months of her stay, Randegger planned to apply for funds to set up “a tuition-free class,” thus meeting an educational need expressed by the community without burdening families with scarce economic means.

As the presence of a single woman provoked the hostility of the religious establishment, who viewed it as a temptation, Randegger gave in to the pressures and decided to marry in order to continue living in Jerusalem and working at her educational project. Her choice of a husband fell on Jacob Friedenberg, a Hungarian who was the grandson of the Chief Rabbi of Transylvania, whose family was not rich but enjoyed distinction for its religious dedication. Shortly before the wedding, Randegger met Sir Moses Montefiore and his wife, who were visiting the Holy Land at the time. The couple attended the wedding and Sir Moses, having expressed an interest in Randegger’s project, promised he would ask the London Committee to grant her a permanent appointment at the girls’ school in Jerusalem.

However, Sir Moses did not keep his promise and Randegger failed to secure the post. Two years to the day after her departure from Trieste, financial strictures forced her to go back. She arrived in Trieste on November 10, 1858, with her husband and a daughter born in Alexandria, Egypt, where they had stopped on their way to Italy.

Return to Jerusalem

In Trieste Randegger tutored students privately until 1864, when she received an invitation from Albert Cohn (1814–1877), who was in charge of Baron de Rothschild’s philanthropic activities, to return to Jerusalem and resume working on her educational projects. Accepting the invitation enthusiastically, Randegger left with her husband and their four children (the older daughter now aged five, the youngest four months old).

In the journal, Randegger describes having to put up with extremely unhealthy lodgings, struggling, apparently together with her husband, against “the fanaticism of ignorance” and suffering a ban by the Ashkenazi rabbis for their decision to retain European dress. The project to open a school for girls (which Cohn had entrusted to Randegger) also met with the hostility of the Ashkenazi community, which held to its 1856 veto against anyone attempting to teach a foreign language or alphabet to Palestinian Jews, a veto originally aimed at the Laemel school started in 1856 by Ludwig August Frankl (1810–1894), representing the Viennese philanthropist Elisa Lippet Herz, née Laemel.

According to Randegger, while the Sephardim displayed a “very tolerant” attitude and welcomed the opportunity to have a school, the Ashkenazim extended their hostility to any school, regardless of whether it was for boys or girls, and even if it claimed to teach exclusively Hebrew and the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah. In 1864 they confirmed the ban against schools in general and schools for girls in particular and against “the woman who came to Holy City to teach girls […] manual skills, writing and languages, for which our hearts tremble in scandal.”

Unable to obtain sufficient financial backing, battling bouts of fever, ophthalmia, and a host of difficulties, Randegger struggled on for over a year, until the cholera epidemics that eventually struck the city finally forced her to return to Trieste with her family.

Journal Publication and Later Life

On publishing the journal in 1869 Randegger declared that, despite the failure of her previous attempts, she would gladly try her educational experiment once again, should an opportunity arise. Indeed, she renewed her plea to her brethren to follow the example of philanthropists lending their help to the Holy Land for God’s greater glory.

In 1875 Randegger submitted to Sir Moses Montefiore, who was setting out on his last visit to the Holy Land, a project for an agricultural school for women in Palestine. He promised to put her in touch with people interested in development programs. Montefiore described Randegger as an important, cultured, and intelligent woman. The realization of her dream, however, fell to others.

Randegger died in Chirignano, near Venice, Italy, at the home of her son, Vittorio, who was the town’s mayor for many years. She was buried on April 28, 1910. According to her obituary, she was a widow and had lost two of her children at a young age; she left a daughter, Marianna, and a son, Vittorio, together with his wife, Emma Ravà, and their children.

Selected Works

Un po’ di tutto. Seconda strenna israelitica di F. S. C. Friedenberg maestra approvata in Trieste, Trieste: 1869; second edition with the title Da Trieste a Gerusalemme. Viaggi in Terra Santa di una giovane maestra ebrea (1856. 1864), Milano: no date.

Bassi, Giuseppe. “Clementina Flora Randegger Friedenberg” (Obituary). Il Vessillo Israelitico 58 (1910): 231–233.

Carpi, Daniel, and Moshe Rinott. “Journal of the Journeys of a Jewish Teacher from Trieste to Jerusalem (1856–1864)” (Hebrew). Kevazim le-heker toledot ha-hinukh ha-yehudi be-Yisrael u-va-tefuzot. February 1982: 115–159.

Carpi, Daniel, and Moshe Rinott. “Sulle orme di Flora Randegger-Friedenberg. I viaggio di una giovane maestra da Trieste a Gerusalemme (1856, 1864).” Annuario di studi ebraici 9 (1985–1987): 271–291.

Ibid. “In the steps of Flora Randegger-Friedenberg.” Ariel 61 (1985): 58–65; Nissim, Daniel. “Due viaggi in Palestina.” La Rassegna mensile di Israel 40 (1974): 256–259.

Wachstein, Bernhard. Die Hebraeische Publizistik in Wien, Vienna: W. Braumuller, 1930.