Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner

Bacteriologist Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner became a specialist on tuberculosis, earning a reputation in Berlin after she discovered the dangers in milk production at one factory in the city. She was honored by Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1912. Although Rabinowitsch-Kempner was both a world-famous scientist and a professor, she often encountered anti-Semitism and was never able to attain an academic position at the University of Berlin. However, as a member of Berlin society and a highly respected woman scientist, she was also editor of the Journal of Tuberculosis and the president of the Association to Support Women Students with Interest-Free Loans. With the rise of Nazism, Rabinowitsch-Kempner was deprived of all her positions in 1933 and died due to illness 1935.

A leading figure in the feminist movement of women scientists in Germany in the first three decades of the twentieth century and an outstanding bacteriologist, Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner was a pioneer among women scientists, an exception among the first generation of women scientists in her combination of career and family.

Family and Education

Lydia Rabinowitsch was born on August 28, 1871, in Kovno (Lithuania), the youngest of nine children, to a wealthy Jewish family whose children all studied at university. Because of the laws that discriminated against women and Jews in her native land, she studied medicine at the University of Bern in Switzerland, receiving her doctoral degree there in 1894. With no possibility of becoming a scientist in Lithuania, Rabinowitsch sought and found work elsewhere, beginning as a guest at the Institute for Infectious Disease in Berlin under Robert Koch (1843–1910). From 1897 until 1898 she held the position of professor for bacteriology at the College for Medicine in Philadelphia in the United States. However, she gave up this position upon meeting the physician and bacteriologist Walter Kempner (1870–1920), whom she followed to Berlin, where they worked for a while under Koch. When they married in April 1898 at an International Congress in Madrid, even newspapers reported the event.

Career

Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner and her husband were a classic couple in science, like the physicists Marie and Pierre Curie and the brain researchers Cécile and Oskar Vogt. They had three children: Robert (1899–1993), a lawyer and prosecutor for the United States in the Nuremberg trials; Nadeshda (1901–1932), a student of Anglo-American literature, who died of tuberculosis; and Walter (b. 1903), who became a scientist.

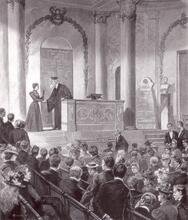

Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner was the second president of the Association to Support Women Students with Interest-Free Loans, which was established in 1900 by the physicist Elsa Neumann (1872–1902). She gave up this position only in the 1920s, when the inflation in Germany made it impossible to continue granting loans.

Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner became a specialist on tuberculosis, earning a reputation in Berlin after she discovered the dangers in milk production at one factory in the city. At first the discovery caused a scandal, but she was later highly honored for it. In 1912 Kaiser Wilhelm II decorated her with the title Professor, whereupon a second scandal occurred, as a result of attacks in antisemitic newspapers. Although Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner was both a world-famous scientist and a professor, she was never able to attain an academic position at the University of Berlin. The Medical Faculty of the university rejected her request for “venia legendi” as lecturer in bacteriology. Several grants and other support enabled her to continue her scientific activities after leaving the Robert Koch Institute, while her husband worked as a physician. From 1918 until 1933 she held the position of director of the bacteriological laboratory at the Berlin Moabit Hospital. She was also editor of the Journal of Tuberculosis (Zeitschrift für Tuberkulose) until 1933–1934. A member of Berlin society and a highly respected woman scientist, Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner was one of the few women listed in the Handbook of German Society (Handbuch der Deutschen Gesellschaft. Berlin: 1930).

In 1933, with the rise of Nazism, Rabinowitsch-Kempner was deprived of all her positions and honors. Thanks to her friends in Philadelphia, both her sons emigrated to the United States. Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner died in Berlin on August 3, 1935 after a severe illness, but with the comfort of knowing that her sons were safe.

Long forgotten, Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner’s work was finally acknowledged after the publication of biographical and scientific works referring to her.

Handbuch der Deutschen Gesellschaft. Berlin: 1930, vol. 1, p. 908, with photo.

Gerber, Klaus. Bibliographie der Arbeiten aus dem Robert-Koch-Institut 1891–1965. Stuttgart: 1966, with a list of publications of Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner and Walter Kempner.

Graffmann-Weschke, Katharina. “Frau Prof. Dr. Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner. Die führende Wissenschaftlerin in der Medizin ihrer Zeit.” In Weibliche Ärzte. Hrsg. Eva Brinkschulte. Berlin: 1994, 93–102.

Graffmann-Weschke, Katharina. Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner (1871–1935). Leben und Werk einer der führenden Persönlichkeiten der Tuberkuloseforschung am Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts. Herdecke: 1999

Graffmann-Weschke, Katharina. Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner (1871-1935): Leben und Werk einer der führenden Persönlichkeiten der Tuberkuloseforschung am Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts. Herdecke: GCA-Verlag, 1999.

Kempner, Robert. M. W. “Ankläger einer Epoche. Lebenserinnerungen.” In Zusammenarbeit mit Jörg Friedrich. Frankfurt/M., Berlin, Wien: 1983.

Kohut, Adolph. Berühmte israelitische Männer und Frauen in der Kulturgeschichte der Menschheit. Lebens- und Charakterbilder aus Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Ein Handbuch für Haus und Familie. Leipzig-Reudnitz: 1900/1901, Vol. 2, p. 424.

Kotzur, Marlene. Steglitz-Frauen setzen Zeichen. Berlin: 1990, 93–95.

Lichtenberg, Georg, Bettina Münchmeyer, and Wolfgang Wölk. Spurensuche in Steglitz. Persönlichkeiten prägen einen Bezirk. Berlin: 1987, 119–120.

Pross, Christian, and Rolf Winau. Nicht mißhandeln. Das Krankenhaus Moabit. Berlin: 1984, 149–151.

Vogt, Annette. “Berlins erste Professorin. Der Milch-Skandal machte sie berühmt. Lydia Rabinowitsch-Kempner—die erste vom Kaiser ernannte Professorin in Berlin.” In Berlinische Monatsschrift (6) Heft 7 (1997): 32–36

Vogt, Annette. Elsa Neumann—Berlins erstes Fräulein Doktor. Hrsg. der Dokumente und Essay. Berlin: 1999, 25–30, 143–144.