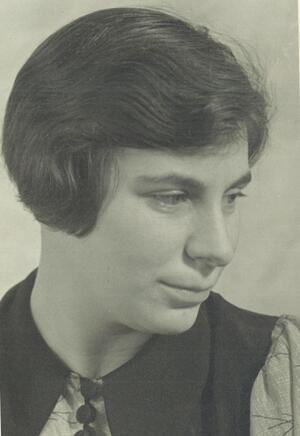

Hilde Levi

Hilde Levi obtained her doctorate in 1934 and followed several other famed German scientists into exile in Copenhagen, where she researched using new information about artificial radioactivity. As part of the second generation of women scientists in Germany, she was able to participate on a relatively equal basis in academia. After the Nazis occupied Denmark, Levi escaped in 1943 to Sweden, where she continued her research. After the war she returned to Copenhagen, studying and teaching about the isotope technique. She also researched in the United States, making new discoveries about carbon dating and autoradiography. Levi continued working until her retirement in 1979 and died in Copenhagen.

Hilde Levi was an exceptional physicist who worked first in Germany and later in her new home country, Denmark, where she became a prominent researcher. She belonged to the second generation of women scientists in Germany, who were able to participate on a relatively equal basis in scientific institutions and in academia.

Early Life

Hilde Levi was born on May 9, 1909, in Frankfurt on Main. She received an excellent education at a gymnasium, which enabled her to continue to university immediately after taking the Abitur examination. She studied physics and chemistry at universities in Munich, Frankfurt/M., and Berlin, becoming a graduate student at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (KWI) for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry in Berlin-Dahlem (the famous Haber Institute) from 1932 until 1934. Given her study at the University of Berlin and her position at the KWI, Levi had a good chance of making a successful scientific career in Germany, but the Nazi accession to power in spring 1933 changed everything.

Early Career

Hilde Levi was able to finish her doctoral thesis in 1934, supervised by Peter Pringsheim (1881–1963) and Fritz Haber (1868–1934), both on their way into exile. Hilde Levi followed them into exile after finishing her Ph.D. thesis. With the help of the Danish branch of the International Federation of University Women, she received a position at the Niels Bohr Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. Here she began work in 1934. One of her first papers was published in exile in 1934, together with the famous physicist James Franck (1882–1964), another German physicist and also a refugee. Beginning in the mid-1930s, she was an assistant to the Hungarian physical chemist George de Hevesy (1885–1966), applying Hevesy’s radioactive indicator technique in biology, an application that had recently been made possible by the discovery of artificial radioactivity in 1934. Up to the German occupation of Denmark in April 1940—when she took up work at the Carlsberg Laboratory, an internationally renowned research institution for biology—she published several papers together with Hevesy.

Although safe in Denmark, Hilde Levi was “punished” by the Nazis when the faculty of the University of Berlin cancelled her doctoral degree in 1938. The Germans occupied Denmark on April 9, 1940, but Hilde Levi succeeded in escaping to Sweden in September 1943. Here she received an appointment at the Wennergren Institute for Experimental Biology in Stockholm, headed by the biologist John Runnström. She worked there until the end of the war.

Postwar Career

After the war, Hevesy remained in Stockholm and Bohr decided to discontinue the biological research that had taken place at his Institute. Hilde Levi was offered a position in Copenhagen at the Zoophysiological Laboratory of the Danish Nobel Prize winner August Krogh, who had cooperated closely with Hevesy before the war. She worked there until her retirement in 1979, during which time she produced a number of scientific papers and was instrumental in spreading the gospel of the isotope technique to students and professionals alike.

Hilde Levi spent the academic year 1947–1948 in the United States, the first of several research visits there. At this first visit she learnt to apply carbon-14 in determining the age of substances containing carbon. The Danish National Museum in Copenhagen soon recognized her expertise in this area and supported her development of an apparatus for age determination based on carbon-14 dating—the first such device in Europe. The apparatus was first put to use in 1951 and made possible the determination of the exact age of the Grauballe Man, a well-preserved corpse which had been immersed in a peat bog for what was shown to be more than two thousand years.

During her visit to the United States Hilde Levi also became familiar with the technique of autoradiography, which the Finsen Institute in Copenhagen then put to use to investigate the side effects of the drug thorotrast. From 1952 to 1970 she was a consultant to the Danish National Board of Health as it developed legislation pertaining to the new field of radiation protection.

Later Life

Hilde Levi studied specific physical problems, among them problems of geochemistry. In 1947 she published a short biographical sketch of the woman physicist Lise Meitner, whom she met personally in Sweden and to whom she had been known since her Berlin years. After her retirement in 1979 Hilde Levi became involved in history of science, developing a close relationship with the Niels Bohr Archive. In particular, she located and photocopied Hevesy’s letters and manuscripts from public and private archives all over the world in order to supplement the Hevesy Papers already at the Archive. This research culminated in the publication in 1985 of her acclaimed biography of Hevesy. Hilde Levi also took the initiative to prepare the Niels Bohr Centennial Exhibition at the Copenhagen Town Hall in 1985.

In 2001 Hilde Levi received an invitation from the University of Berlin to participate in an event honoring former students who had been dismissed in 1933 and were then living all over the world.

Never married, she spent her last years at a rest home in Copenhagen, where she died on July 26, 2003, at the age of ninety-four.

Selected Works by Hilde Levi

Beutler, H. and H. Levi. “Über die Spektren der Alkalihalogen-Dämpfe.” In Zeitschrift für Elektrochemie Nr. 8a (1931):1–6.

Levi, Hilde. “Lise Meitner.” In Store Kvinder. edited by Edith Rode og Kis Pallis, 289–300. Kobenhavn: 1947.

Levi, Hilde. “George de Hevesy: August 1885–July 1966.” Nuclear Physics A 98 (1967): 1–24.

Arrhenius, Gustav, and Hilde Levi. “The era of cosmochemistry and geochemistry, 1922–1935.” In George de Hevesy Festschrift. Budapest: 1988, 11–136.

Levi, Hilde. George de Hevesy. Copenhagen: 1985.

American Institute of Physics, Oral History Interviews with Hilde Levi at https://www.aip.org/history-programs/niels-bohr-library/oral-histories/5038.

Archive Berlin University (Archiv HUB): Phil. Fak. Nr. 757, 130–153.

Archive SPSL, Oxford: file 333/12.

Cambridge, Churchill College Archive, Lise Meitner papers (correspondence Meitner-Levi).

List of Displaced German Scholars. London: 1936.

Lewis, J. M. "WAVES Forecasters in World War II (with a Brief Survey of Other Women Meteorologists in World War II)." Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 76, no. 11 (1995): 2187-202.

Nolte, Peter. Spurensuche. Kommilitonen von 1933. Berlin: 2001, 36.

Vogt, Annette. Women scientists in Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes, from A to Z (Dictionary). Berlin: 1999, 82–83.