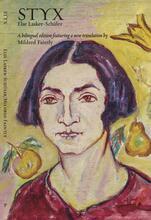

Else Lasker-Schüler

Else Lasker-Schüler was born in Elberfeld (today Wuppertal), Germany, in 1869, the sixth and youngest child of an assimilated upper-middle class family. Early in her literary career, her poetic genius allowed her to create poems in which sound, image, and meaning illuminate each other with a limitless ability to form new word combinations (compounds). Most of Lasker-Schüler’s prose writings are essayistic in nature: portraits of artists, reviews of theater and cabaret, even circus performances. In the fictitious Briefe nach Norwegen (Letters to Norway, 1911), she portrays herself among the Berlin coffee house bohemians. The work is both a vivid picture of 1910 Berlin emerging as cultural capital and a very personal testimony of Lasker-Schüler’s life: alone but independent. Lasker-Schüler died in Jerusalem in January 1945.

“I was born in Thebes, Egypt although I came into the world in Elberfeld in the Rhineland.” This is how Else Lasker-Schüler characterized her background, indicating the separation between imagination and reality, artistic and bourgeois existence that marked her life. To speak for her she created the persona of Jussuf, Prince of Thebes, her alter ego who appears in her writings and drawings and with whose name she often signed her letters. This figure has an important Jewish component. Her Egyptian Jussuf is in fact the biblical Joseph, with whom Else Lasker-Schüler identified already as a child. He is Joseph the dreamer and poet, ridiculed by his brothers, betrayed and sold.

But he never forgets his people. Elevated to a position of power, he forgives and saves the starving Israelites. Lasker-Schüler was an uncompromising poet who had to suffer economic deprivation and was scorned by conservative critics and bourgeois readers, Jews and non-Jews alike. But she considered it her mission to remind her people of their great history and the biblical forebears of whom they should be proud, just as she was proud to be a Jew. “I am Jewish, thank God,” she proclaimed. The Prince of Thebes therefore was the incarnation of all that reality denied her: power and wealth. He was able to bestow precious gifts upon his artist friends and to lead the avant-garde in the fight for a new art, and thus for the renewal of the world.

Personal Life and Family

The world in which Lasker-Schüler grew up was the world of the assimilated upper-middle class. She was born on February 11, 1869, as the sixth and youngest child of Aron Schüler (1825–1897), a banker and builder, and his wife Jeannette née Kissing (1838–1890), in the industrial city of Elberfeld (today part of Wuppertal). Her family history reflects the rise of German Jews in the nineteenth century: her great-grandfather was a teacher and rabbi in a Westphalian village. One of her mother’s cousins, Leopold Sonnemann (1831–1909), founder of the liberal Frankfurter Zeitung, became a member of the Reichstag (parliament). She herself ranks among the greatest poets of the German language.

Elisabeth (Else) Schüler had a comfortable, protected childhood, which she described in many autobiographical texts. Her father appears as a happy-go-lucky fellow who provides his family with an elegant house and sends his three sons to boarding schools and his three daughters to a progressive girls’ school in Elberfeld. Lasker-Schüler adored her mother, an avid reader who spent much time with her youngest child. “She was the real poet,” Lasker-Schüler said of her, “I only told her verses.” Her siblings were considerably older. Her brother Alfred (1858–1932?), who became a painter, was eleven years her senior.

Her youngest brother Paul (1861–1882), whom she loved most, died at the age of twenty-one, just when she turned thirteen. Her sister Martha (1862–1915), who married when Lasker-Schüler was fourteen and emigrated to the United States with her husband, was seven years older. Anna (1863–1912), the only child who married a Christian, and to whom Lasker-Schüler was closest, was six years older.

Early Literary Career

Lasker-Schüler left school either at the age of thirteen, or at fifteen, according to her for health reasons. Others suspect that antisemitic taunts by her schoolmates caused a severe nervous disorder (chorea minor) in the sensitive child. After she recovered she was taught at home. Her mother’s death when Lasker-Schüler was twenty-one she later described as a catastrophe of cosmic proportions. In 1894 she married Berthold Lasker (1861–1928), a physician who was interested in literature, and moved to Berlin with him. Although she lived in comfortable circumstances and took art lessons, it was an unhappy marriage. She insisted that the father of her son Paul, born in 1899, was a Greek prince. He has never been identified.

Lasker-Schüler’s first poems were published that same year, when she began to move in Berlin literary circles. There she met the pianist and composer Georg Levin (1878–1941), whom she named Herwarth Walden and whom she married after her divorce in 1903. Together with him she fought on behalf of the modern movement in literature, music and art. In 1904 Walden founded the Verein für Kunst (Art Association). All the great names of the Moderns, including that of Lasker-Schüler, appeared in its programs of readings, concerts, and dance performances. In 1910 Walden founded the journal Der Sturm (The Storm) which published the young Expressionist poets and artists and more than one hundred poems and prose texts by Lasker-Schüler.

After her divorce from Walden in 1912, Lasker-Schüler continued to live in Berlin, supporting her son, himself a gifted artist but of such delicate health that he was never able to be independent. Diagnosed with tuberculosis in February 1926 while in a Munich hospital, he was taken to Switzerland, where he was hospitalized in a number of sanatoria. He spent the last weeks of his incurable illness with his mother in Berlin, where he died in December 1927. During these years of enormous financial difficulties, Lasker-Schüler depended on her art work for survival. Her highly original pen-and-crayon drawings and her collages depict the oriental realm of Prince Jussuf with his servants, warriors and musicians and the city of Thebes. The deluxe-portfolio edition of Thebes comprising ten poems and ten lithographs, appeared in 1923; two hundred copies were hand-colored by the artist. She also designed the covers of the ten-volume edition of her collected works published by the renowned Paul Cassirer Verlag in 1919/20. In the 1920s another motif is added to that of Prince Jussuf’s Orient: Now the South American Indian serves as another incarnation of artistic strength, freedom, and beauty. Like her prose and poetry, Lasker-Schüler’s drawings are highly original. One cannot detect the influence of any other artist nor can she be compared to any of her contemporaries.

Fleeing Berlin to Switzerland

Lasker-Schüler fled her beloved Berlin in March of 1933 for Zürich, Switzerland after having been honored with the Kleist Prize the previous year. She had reached the pinnacle of her success and popularity. Since her marriage and collaboration with Herwarth Walden, she had stood at the center of the artistic community in Berlin. The entire Expressionist generation were among her admirers. Her poems appeared in all important avant-garde journals and anthologies, including Das Kinobuch, a 1914 collection of film scenarios edited by Kurt Pinthus (1886–1975). None of the scripts was ever made into a movie, but Lasker-Schüler became a passionate moviegoer for the rest of her life. She was painted by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884–1976) and Jankel Adler (1895–1949), among others. The most famous friendship between Lasker-Schüler and a fellow artist was that with the painter Franz Marc (1880–1916), who sent her dozens of postcards with watercolors depicting mostly animals, the so-called “Messages to Prince Jussuf.” Karl Kraus (1874–1936) praised her in his journal Die Fackel. She gave readings throughout Germany, in Prague, Vienna and Zürich. She was also frequently invited by radio stations to read her poetry and prose. By the time she had to flee, her fame had spread even further. The first translation, into English, appeared in 1909, and she was now translated into French and Hebrew.

Years in Israel

From Zürich, Lasker-Schüler made two trips to Palestine: in 1934 and 1937. From the third in 1939 she was unable to return. She lived in Jerusalem, supported by the Jewish Agency and the publisher Salman Schocken (1877–1959). Ill health and difficult living conditions prevented her from being very productive in her later years. Nevertheless she wrote some of her best love poems, contained in her last book, Mein blaues Klavier (My Blue Piano), published in Jerusalem in 1943, and an extraordinary play IchundIch (IandI, 1940/4). With her literary club, Der Kraal, to which she invited such speakers as Martin Buber (1878–1965), Hugo Bergmann (1883–1975), and Ernst Simon (1899–1988), she sought once more to create an artistic and spiritual environment even under the most adverse circumstances. She died in Jerusalem on January 23, 1945 and was buried on the Mount of Olives.

Lasker-Schüler’s fame is mainly based on her poems, in which she early on, around 1900, found her own language, even while still under the influence of the art nouveau movement. Soon afterwards she wrote love poetry and poems in praise of her artist friends in an incomparable, new idiom. In her Hebräische Balladen (Hebrew Ballads) she glorifies great biblical figures. Her poetic genius allowed her to create poems in which sound, image, and meaning illuminate each other. Her ability to form new word combinations (compounds) was limitless.

Literary Themes and Motifs

Much of her early imagery is inspired by her imagined Orient, where many European poets and artists of the time sought to renew their creative energies. Her infatuation with East Asia is most evident in her early short pieces. There the protagonist appears as Tino, Princess of Bagdad, a poet and dancer who later changes into Jussuf Prince of Thebes. This change from a female to a male protagonist clearly expresses an emancipatory stance. Only the Prince could have gone to war to fight for a new art and a new society alongside his artist-comrades, among them “the wild Jews.” Lasker-Schüler also wanted to perform her Eastern stories and poems on stage. Around 1910 she expended enormous time and energy on a performance project which came to naught. Most of Lasker-Schüler’s other early prose writings are essayistic in nature: portraits of artists, reviews of theater and cabaret, even circus performances. In the fictitious Briefe nach Norwegen (Letters to Norway), first published in Der Sturm and later as the novel Mein Herz (My Heart), she portrays herself among the Berlin coffee house bohemians. The work is both a vivid picture of Berlin emerging as cultural capital around 1910 and at the same time a very personal testimony of a woman artist about to start a new life, alone but independent. The short narrative Der Wunderrabbiner von Barcelona (The Miracle Rabbi of Barcelona) is a visionary text about a pogrom in a Spanish city from which a Jewish girl and her Christian bridegroom escape and where the collapsing temple, which Lasker-Schüler describes as a building with columns and a cupola, kills the Christian population.

Several essays from the 1920s and 1930s collected in the volume Konzert show her deep, mystical love of nature and her equally deep religiosity. After her first trip to Palestine she wrote the travelogue Das Hebräerland (Land of the Hebrews), an embellishing account, designed to enhance the image of a country where she wished for nothing more than the reconciliation of “two stepbrother peoples.” Her three plays are very different from one another. Die Wupper, named for the river of her hometown, was completed in 1909 and first performed in 1919. It depicts a society whose members, although separated by class, are nevertheless connected by sexual impulses and desire. Arthur Aronymus und seine Väter (Arthur Aronymus and His Fathers) is loosely based on her family’s history in rural Westphalia, with her young father as the protagonist. Written during the rising Nazi violence in Berlin in 1932, it is the counterpart of the Miracle Rabbi of Barcelona, in which the two faiths are irreconcilable. Arthur Aronymus and his Fathers was first performed in Zürich in 1936. It is Lasker-Schüler’s moving and urgent appeal to combat antisemitism and to realize that Judaism and Christianity grew from the same root. In IchundIch (IandI), written in Jerusalem in 1941, she sums up her life, work and times in a fantastic, baroque world theater using the legend of Faust to depict the future demise of Hitler and his cohorts.

Legacy

Lasker-Schüler’s activist nature comes out most clearly in Ich räume auf! (I’m Cleaning Up!) her polemic against her publishers, in which she sides with all the poets who are as poor as herself. Her activism is also evident in the thousands of letters she wrote. She was not above begging for financial support and good reviews for others; she protested against the maltreatment of animals; she joined political demonstrations in Berlin when Nazis tried to prevent the screening of All Quiet on the Western Front, and in Jerusalem when the British Government published the White Paper limiting immigration to Palestine just when World War II started. In 1914 she had traveled to Moscow to try and free the imprisoned young anarchist Johannes Holzmann, but to no avail. In 1944 she wrote to Pope Pius XII urging him to speak out against the persecution of Jews. In Jerusalem her friends were those German-speaking Zionists, such as Buber, Bergmann and Simon who favored a bi-national Palestine. The proposals in her letters to Salman Schocken to build schools for poor Arab children and playgrounds with merry-go-rounds for all the children of the city, are evidence of her conviction that only cooperation between Arabs and Jews would serve both people. She never joined a political party but supported socialist causes in her writings and by participating in various campaigns.

Although she expressed her reservation about the organized women’s movement, she frequently advocated women’s causes such as the right to end a pregnancy. Even her language expresses her concern for equal treatment of women. Now, decades after her death, a “gender-just” German language with feminine forms placed alongside masculine ones is becoming current—a practice which Lasker-Schüler followed without exception. Her entire life and work are a testimony to the truly independent and liberated woman she was.

WORKS BY ELSE LASKER-SCHÜLER

Styx (Poems, 1902).

Der siebente Tag (The Seventh Day. Poems, 1905).

Das Peter Hille-Buch (The Peter Hille-Book. Prose, 1906).

Die Nächte Tino von Bagdads (The Nights of Tino of Bagdad. Prose and Poems, 1907).

Die Wupper (Play, 1909).

Meine Wunder (My Miracles. Poems, 1911).

Mein Herz. Ein Roman mit Bildern und wirklich lebenden Menschen (My Heart. Novel with drawings, 1912).

Gesichte. Essays und andere Geschichten (Visions. Essays and other Stories. Prose portraits and essays, 1913).

Hebräische Balladen (Hebrew Ballads. Poems, 1913).

Der Prinz von Theben. Ein Geschichtenbuch (The Prince of Thebes. A Storybook. Prose, 1914).

Der Malik (Prose, 1919).

Der Wunderrabbiner von Barcelona (The Miraculous Rabbi of Barcelona. Prose. 1921).

Ich räume auf! Meine Anklage gegen meine Verleger (I’m Cleaning Up! My Indictment of My Publishers. Prose, 1925, 1932).

Arthur Aronymus. Die Geschichte meines Vaters (Arthur Aronymus. The Story of my Father. Play, 1932).

Konzert (Concert. Prose and Poems 1932).

Das Hebräerland (Land of the Hebrews. Prose, 1937).

Mein blaues Klavier (My Blue Piano. Poems, 1943).

Margarete Kupper ed., Lieber gestreifter Tiger; Wo ist unser buntes Theben (Two volumes of selected letters, 1969).

Ulrike Marquardt, Heinz Rölleke eds., Else Lasker-Schüler/Franz Marc: Mein lieber, wundervoller blauer Reiter (Private correspondence of Lasker-Schüler and Marc with excellent reproductions of their graphic art, 1998).

Norbert Oellers, Heinz Rölleke, Itta Shedletzky eds.,Werke und Briefe. Kritische Ausgabe (Critical edition of works and letters with extensive commentary: Vol. 1 Poems. Vol. 2 Plays. Vol. 3 Prose 1903–1920. Vol. 4 Prose 1921–1945. Posthumous Writings; Vol. 5 Das Hebräerland. Vol. 6 Letters 1893–1913. (1996–2003).

Translations into English:

Durchslag, Audri and Jeanette Litman-Demeestère. Hebrew Ballads and other Poems (1980).

Newton, Robert P. Your Diamond Dreams Cut open My Arteries (Translations of Poems, 1982).

Snook, Jean M. Concert (1994).

Bauschinger, Sigrid. Else Lasker-Schüler. Ihr Werk und ihre Zeit. (Extensive, illustrated monograph with a catalogue raisoné of drawings, 1980).

Bauschinger, Sigrid. Else Lasker-Schüler. Biographie. Göttingen: 2004.

Bellenberg, Karl. Else Lasker-Schüler, ihre Lyrik und ihre Kompoisten. Berlin: 2019.

Hessing, Jakob. Die Heimkehr einer jüdischen Emigrantin. Else Lasker-Schülers mythisierende Rezeption 1945–1971 (Critical evaluation of Lasker-Schüler’s reception in Germany after World War II among literary critics and in the media, 1993).

Hessing, Jakob. Else Lasker-Schüler. Biographie einer deutsch-jüdischen Dichterin (The biography stresses Jewish aspects of her life and works, 1985).

Klüsener, Erika. Lasker-Schüler In Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten. (Concise, well documented, illustrated biography, 1980).

Klüsener, Erika and Friedrich Pfäfflin, eds., Else Lasker-Schüler 1869–1945. (Chronology of her life and works with rare documents, including reviews and illustrations from the German Literary Archives, 1995).

Jones, Calvin N. The Literary Reputation of Else Lasker-Schüler: Criticism 1901–1993. (Most comprehensive bibliography to date in print, 1994).

Hallensleben, Markus. Else Lasker-Schüler. Avantgardismus und Kunstinszenierung. (Interpretation of her works in context with the European avantgarde movement , 2000).

Lasker-Schüler Almanach (Papers of uneven quality mainly on biographical topics, edited by various editors commissioned by the Lasker-Schüler Society 1993, 1995, 1997, 2000).

Bluhm, Lothar and Andreas Meyer, eds. Else Lasker-Schüler Jahrbuch zur klassischen Moderne 1. (Scholarly articles of high quality on various aspects of her life and work, 2000).

Falkenberg, Betty. Else Lasker-Schüler. A Life. (First full-length biography in English, 2003).

See also the Lasker-Schüler website: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~markhall/elsch.html

Karl Bellenberg: Else Lasker-Schüler, ihre Lyrik und ihre Kompoisten.

wbv Berlin. 2019.