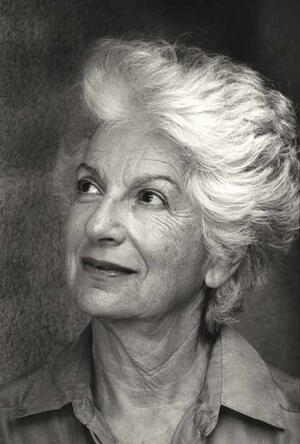

Shirley Kaufman

Shirley Kaufman grew up in Seattle and received her BA from UCLA in 1944, later entering the creative writing program at San Francisco State University. Her first volume of poetry, The Floor Keeps Turning (1970), won the First Book Award of the International Poetry Forum in Pittsburgh. A second volume, Gold Country (1973), was received with great critical acclaim. Kaufman later moved to Israel, where her poetry took on themes of dislocation and the immigrant experience in the United States. She has been praised for her honest portrayal of mother-daughter relationships and wrote a series of poems about the suffering of women in the Bible, set in modern Israel. Kaufman also translated many Hebrew poets and was the chief editor of a bilingual anthology of poetry in Hebrew by women in 1999.

Overview and Early Life

Shirley Kaufman’s oeuvre, though slender, belongs to the poetry of permanent value written in the last quarter of the twentieth century. She began publishing relatively late in her life, in her forties, but from the time that her first volume, The Floor Keeps Turning, appeared in 1970, she continued to produce brilliantly etched lyrics of increasing complexity and depth over the following four decades. Kaufman’s strength as a lyricist has paradoxical origins, emotional and aesthetic. Despite her declared existential unease in the world (her volume of selected poems, published in 1996, is entitled Roots in the Air), her poetry finds its source not in the air but in her unselfconscious sense of herself as a woman, her strong relationship to family, and her sometimes conflicted but always strong Jewish identity. The aesthetic paradox is that this poetry, though often characterized by raw emotion, is contained within a modernist style of strictly disciplined, objective language.

Kaufman was born on June 5, 1923, to parents who had immigrated to the United States from Poland. Her mother, Nellie (Nechama) Freeman, a homemaker, was born near Brest-Litovsk in 1895 and arrived in the United States in 1913. Her father, Joseph Pincus, born in Ulanow, Galicia, in 1896, immigrated to the United States in 1918; he was a furniture salesman and later a furniture wholesaler and manufacturer. Her parents were married in Seattle, Washington, in 1921.

Kaufman grew up in Seattle and received her BA in English literature from UCLA in 1944. In 1946 she married her first husband, Dr. Bernard Kaufman, Jr., who was a cardiologist in San Francisco. They had three daughters: Sharon (b. 1948), Joan (b. 1950), and Deborah (b. 1955).

Early Writing Career and Move to Israel

It was not until her three daughters were in their teens that Kaufman turned full-time to writing, when she entered the creative writing program at San Francisco State University. Her apprenticeship was with such writers as Gary Snyder, Kenneth Rexroth, Robert Duncan, and George Oppen. At the same time, she encountered the Spanish surrealists, who left a powerful stamp upon her style. Her first volume of poetry, The Floor Keeps Turning (1970), won the First Book Award of the International Poetry Forum in Pittsburgh. A second volume, Gold Country (1973), was received with great critical acclaim.

Kaufman divorced in 1974 and married Hillel Matthew Daleski, professor of English Literature at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The move to Israel introduced a new dimension of dislocation into Kaufman’s poetry—what she called a “sense of suspension, of dangling between places...I’ve always felt it very deeply,” as she told Gabriel Levine in an interview. “First, growing up in Seattle as an only child to immigrant parents. …I was very much aware of their having come from the Old Country. … And second, my moving to Israel in 1973. … In a sense I’ve felt all along that I’m living between two cultures, two languages, two identities” (The Jerusalem Post Magazine, 1997).

Out of the first sense of dislocation, the immigrant experience in the United States, came some of Kaufman’s most moving poetry: about her mother, her father, her aunts, her grandparents. In “Nechama” she describes her mother: “They changed her name/to Nellie. All the girls./To be American./And cut her hair.//… She couldn’t give up what she thought she lost./… She was Anna Karenina/ married to somebody else. …” In the poem ironically entitled “The Winning of the West,” she looks at her grandparents in Seattle: “Nights when their faces press hard/at the windows and their scalps shine/pink and almost transparent/under the thin hair, their breath/makes thumbprints on the glass.//Grandpa sucks on a cube/of sugar, sipping his tea.//They are all in the kitchen/with their new names,/stirring the rusty language,/spilling it into their saucers/to let it cool.//… My grandmother fell down the stairs/and broke her hip. She died/in a Catholic hospital…//Her wig’s on the night stand,/stiff little nest/the birds have abandoned.”

From her earliest work Kaufman was deeply engaged with the mystery of suffering, the randomness and cruelty of fate. Poems such as “Turtles,” “Beetle on the Shasta Daylight”(1970) and “The Burning of the Birds”(1973) contemplated mankind’s violence and indifference to the agony of others in lucid, quiet narratives, harrowing in their objectivity. The move to Israel only deepened and reinforced Kaufman’s engagement with the insensate cruelty of history. Always a Zionist, she had been deeply involved in the fate of the Jewish people while still living in the United States, but her direct encounter with Israeli reality broke through the subtle veil between observer and object, between outer and inner. In Looking at Henry Moore’s Elephant Skull Etchings in Jerusalem During the War (1977), the first book she published after moving to Israel, Kaufman makes a surrealist trip into the etchings, contemplating birth and love and death, within the uneasy mad continuum of her new home: “There’s an elephant inside me/crowding me out/he sees Jerusalem/ through my eyes my skin//… I see bodies in the morning kneel/over graves and bodies under them/the skin burned off/their bones laid out in all the cold/tunnels under the world. …” In another poem of that period, “Stones,” the same surrealist breaking of barriers between inner and outer, between animate and inanimate, creates a sense of the claustrophobia of living in Jerusalem: “When you live in Jerusalem you begin/to feel the weight of stones./You begin to know the word/was made stone, not flesh.//They dwell among us. They crawl/up the hillsides and lie down/on each other to build a wall.//… Sometimes at night I hear them/ licking the wind to drive it crazy./There’s a huge rock lying on my chest/and I can’t get up.”

Family and Feminist Themes

Kaufman’s skill at depicting relationships, especially family ties, was unparalleled. Certainly her greatest gift to twentieth-century poetry was the honesty with which she presented the mother-daughter, daughter-mother relationship. She confessed her feelings of guilt towards her mother in poems such as “Nechama,” “Apples,” and “The Accuser.” Perhaps her most anthologized poem is “Mothers, Daughters” in which she describes with heroic candor the struggle between herself and one of her adolescent daughters: “Through every night we hate,/preparing the next day’s/war. She bangs the door./Her face laps up my own/despair, the sour, brown eyes,/the heavy hair she won’t/tie back. …” This poem appeared in her first collection and throughout the years she returned to this flawed relationship; in poems such as “For Joan at Eilat”(1973), “The Mountain”(1979), “Milk”(1993), “Each year more alien”(2002) and “Shell-Flowers” (2002), she tried again and again to understand the frustration of mother-love against a background of painful estrangement.

The same psychological insight and empathetic intuition that inform Kaufman’s poems about her family were the base of a whole series of poems about women in the Bible, practically a sub-genre in her poetry (“His Wife” and “Rebecca”(1970), “Michal”(1973), “Leah”(1979), “Abishag” and “Déjà Vu” (1984), “The Wife of Moses”(1993), “Job’s Wife”(1998), “In the Beginning”(1999), “The Death of Rachel” (2000) and “Yael” (2001). Kaufman succeeded in endowing these shadowy “wives” with an innerness the Bible does not provide. Often she places them in a contemporary Israeli setting and casts an ironic eye upon the gap between the tragi-comic contemporary scene and the tragedy of the actual woman. In “DéjàVu,” Sarah is a guide showing tourists round the Temple Mount and Hagar “is on her knees/in the women’s section praying. … Sarah wants to find out what happened/to Ishmael but is afraid to ask./Hagar’s lips make a crooked seam/over her accusations.” In a surrealist palimpsest, the biblical Rachel is a Bedouin woman stirring soup next to Rachel’s Tomb in “The Death of Rachel”: “All day she stirs the soup/while the tourists park their cars/on the side of the road to visit/her tomb. Soldiers stand on guard/Barren women sway in their scarves/and pray for a child. …// She has been ready for a long time/listening to the calm of the desert/between her pains./She strains till the last one in her/forces his dark head out./She stirs the dust into dust.”

Translations and Legacy

Kaufman also made a major contribution to the link between contemporary Hebrew poetry and the world of English letters by her many excellent translations, based upon close collaboration with the poets themselves. While she was still living in San Francisco, she translated and published some of the works of the Vilna ghetto hero and Israeli poet Abba Kovner (My Little Sister, 1971, and A Canopy in the Desert: Selected Poems, 1973). After her move to Israel, she translated the Israeli poet Amir Gilboa (The Light of Lost Suns: Selected Poems, 1979). Her translation of poetry by many other Hebrew poets, among them Dan Pagis, Avner Treinin, Hamutal Bar Yosef, and Yehuda Amichai appeared in journals overseas. The Flower of Anarchy, the selected poems of Israel Prize winner, Meir Weiseltier, appeared in 2003. In another major contribution to both Hebrew letters and the discovery of women’s poetry, Kaufman was chief editor of a bilingual anthology of poetry in Hebrew by women, The Defiant Muse: Hebrew Feminist Poems from Antiquity to the Present (1999). Kaufman also translated the poetry of the distinguished Dutch Jewish poet, Judith Herzberg.

Shirley Kaufman was not a militant feminist, but her poetry made a unique contribution to English letters and to the development of female and male consciousness in the late twentieth century. With amazing candor she unveiled the voice of a woman speaking as a woman, about the subjects which concern women: childbirth, family relationships, hate, envy, love, personal identity, aging and death, the horror of violence and cruelty and the helplessness of victims, the meaning of Jewish fate. All of this she did in exquisitely crafted lyrics, poems of permanent value to the English-American canon.

SELECTED WORKS BY SHIRLEY KAUFMAN

Original Poetry

The Floor Keeps Turning. Pittsburgh: 1970.

Gold Country. Pittsburgh, 1973.

Looking at Henry Moore’s Elephant Skull Etchings in Jerusalem During the War (with Moore Etchings). Greensboro, North Carolina: 1977, second edition, 1979; Hebrew translation by Dan Pagis, Tel Aviv: 1980.

From One Life to Another. Pittsburgh: 1979.

Claims. New York: 1984.

Rivers of Salt. Port Townsend, Washington: 1993.

Roots in the Air: New and Selected Poems. Port Townsend, Washington: 1996.

Me-Hayyim le-Hayyim Aherim (selected poems in Hebrew translated by Aharon Shabtai, Dan Miron and Dan Pagis). Jerusalem: 1995).

Un abri pour nostêtes (selected poems in French translated by Claude Vigée). Bilingual edition, Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, France: 2003.

Threshold. Port Townsend, Washington: 2003.

Translations

My Little Sister, translated from the Hebrew of Abba Kovner. London: 1971.

A Canopy in the Desert, translated from the Hebrew of Abba Kovner. Pittsburgh: 1973.

Scrolls of Fire, translated from the Hebrew of Abba Kovner. Tel Aviv: 1978.

The Light of Lost Suns, translated from the Hebrew of Amir Gilboa. New York: 1979.

My Little Sister (revised) and Selected Poems 1965–1985, translated from the Hebrew of Abba Kovner. Oberlin, Ohio: 1986.

But What: Selected Poems of Judith Herzberg, translated from the Dutch with Judith Herzberg. Oberlin, Ohio: 1988.

Chametzky, Jules. "Amos Oz, Shirley Kaufman, Abba Kovner." In Out of Brownsville: Encounters with Nobel Laureates and Other Jewish Writers, 71-74. University of Massachusetts Press, 2012.

Kaufman, Shirley, Galit Hasan-Rokem and Tamar Hess. The Defiant Muse: Hebrew Feminist Poems from Antiquity to the Present: A Bilingual Anthology. New York: 1999, London: 2000.

Kearful, Frank J. “Shirley Kaufman’s Art of Turning.” In The Mechanics of Mirage: Postwar American Poetry, edited by Michal Delville, Christine Pagnoulle, 253–275. Liege: 2000.

Idem. “Roots in the Air: The Poetry of Shirley Kaufman.” Literaturwissenschaftliches Jahrbuch, 303–329. Berlin: 2001.

Miller-Duggan, Devon. Jewish American Women Writers: A Bio-bibliographical and Critical Sourcebook, edited by Ann R. Shapiro, 158–164, Westport, CT: 1994.

Recordings

Intricate Lives, Watershed Tapes, Washington, D.C.: 1979.

Selected Poems, Archive of Recorded Poetry and Literature, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.: 1974, 1994.

Videotapes

American Poetry Archives, The Poetry Center, San Francisco State University: February 13, 1975, March 5, 1987, April 1, 1993 and April 15, 1998.

Selected Interviews

Grace Schulman. “Always an Exile.” The Women’s Review of Books, July 1991.

Ken Weisner. “Rivers of Salt.” Sifrut Literary and Arts Review, Summer 1993.

Gabriel Levin. Jerusalem Post Magazine, May 10, 1997.

Chana Bloch. Poetry Flash (Berkeley), November-December 1998.

Lisa Katz. Source, University of Orleans, France, 2002 and The Drunken Boat, Spring/Summer 2003.

Eve Grubin. CROSSROADS: Journal of the Poetry Society of America, Fall 2004.