Health Activism, American Feminist

Since the late 1960s, Jewish women have helped create and sustain the women’s health movement through decades of substantial social, political, medical, and technological change. Jewish women helped build the feminist women’s health movement in the United States, from Therese Lasser’s work in the 1950s on behalf of women with breast cancer, through the birth of the Boston Women’s Health Collective and its pioneering Our Bodies Ourselves in the early 1970s, to the creation of the National Women’s Health Network in the 1970s and the work of twenty-first century women’s health activists. In the twenty-first century, Jewish women continue to redefine health activism as the movement navigates new women’s health concerns and changes in the health politics landscape.

Introduction: History of Feminist Health Activism

American women have been the “perennial health care reformers.” According to sociologist Carol Weisman, a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Public Health Sciences and health policy researcher at the Penn State College of Medicine: “Activism around women’s health has tended to occur in waves and to coincide with other social reform movements, including peaks in the women’s rights movements.” At all of those pivotal moments, Jewish women have played central roles.

In the nineteenth century, the Popular Health Movements of the 1830s and 1840s focused on health education and the promotion of healthy lifestyles, emphasizing such things as proper diet, exercise, and dress reform to eliminate corsets. These movements also included a reaction against the role of elitist, formally trained physicians who advocated extreme treatments. Lay practitioners, including midwives, were promoted as a way of returning some degree of control to women.

In the twentieth century there were four distinct periods of innovative women’s health activity. The first was spearheaded by progressive, wealthy women in 1913, when a New York Times headline announced, “Rich Women Begin a War on Cancer.” This was the origin of the American Cancer Society, first titled the American Society for the Control of Cancer. The aim of these affluent, reform-minded women was to substitute a “message of hope and early detection” for the fear, denial, secrecy, and despair attached to cancer diagnoses.

Following World War II, “transitional activists” of the 1950s to the 1960s maintained that patients are entitled to a voice in selecting their own childbirth options and medical treatments. Susan Brownmiller later called these brave women “our heroic antecedents,” since they lacked the benefit of support from a concurrent women’s rights movement. Two of the most influential “heroic antecedents,” Terese Lasser and Sherri Finkbine, were Jewish. Neither was a troublemaker before her “epiphany,” but as Naomi Bliven (also Jewish) wrote in The New Yorker: “Behind almost every woman you ever heard of stands a man who let her down.” The men who “let down” Terese Lasser and Sherri Finkbine were their doctors.

From the late 1960s to the early 1980s activists demanded informed consent and full partnership in their own health care, as well as full disclosure and scientific proof that benefits of their medical treatments outweighed the risks. Sociologist Sheryl Burt Ruzek, Emeritus Professor of Public Health at Temple University, notes that these “militant activists” of the late 1960s and 1970s “questioned medical orthodoxies particularly around birth practices, hormone products and cancer treatment and prevention.” Ruzek continues: “Looking back now at the early days of the women’s health movement in the late 1960s, it seems almost incredible how hard it was to get access to medical information unless you were a doctor—and most doctors were men.” The idea of women creating “observational” data out of their own health and body experiences was truly “revolutionary.” Post-World War II feminist advocacy to combat sex discrimination in all spheres of life (social, political, economic, and psychological) surfaced with the forming of the National Organization of Women (NOW) in 1966. By the late 1960s, the exploitation of women in health care became a “hot topic.”

Beginning in 1969, a body of protest literature, the forming of new organizations, radical action, and civil disobedience concerning health and medicine rapidly evolved into a recognizable feminist women’s health movement. Pioneering and path-finding groups included the Boston Women’s Health Collective, later known by the name of its groundbreaking health manual Our Bodies, Ourselves; D.C. Women’s Liberation; the National Women’s Health Network in Washington, D.C.; and the Feminist Women’s Health Center in Los Angeles. These groups and others created a matrix and an information network that influenced hundreds of thousands of women in the United States and worldwide to form their own grassroots organizations and join the effort that documentary filmmaker Margaret Lazarus would name Taking Our Bodies Back (Cambridge Documentary Films, 1974). Most of these women were young; many had been active in the civil rights, anti-war and students’ movements of the 1960s. Middle-aged and older women were drawn to the movement as well. By the 1980s “professional advocates,” including doctors, scientists, legislators, lawyers, judges, and corporate executives, entered the broadening women’s health movement in substantial numbers.

By 1998, Ruzek, among others, lamented that it was hard to tell if the interests of patients had been served by the “professional advocates,” institutionalized, or co-opted. Many of the newer facilities and “happenings” in the name of women’s health seemed suspiciously market-driven, providing points of sale for screening procedures and therapies that might or might not be safe and effective. But this new generation of professional activism began with a sincere focus on research, deriving its momentum from the lack of inclusion of women as research subjects in clinical studies. A Jewish doctor, Florence Haseltine of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and a Jewish nurse, Ruth Merkatz at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), spearheaded campaigns to ensure the same gold standards on products for women that were already applied to products for men.

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, feminist women’s health activism is being redefined and reimagined by new generations of activists, as well as by longtime participants in the women’s health movement. Debates about the role of professional advocates, co-optation, and the influence on women’s health advocacy of pharmaceutical industry donations and public relations campaigns continue. Although many of the feminist women’s health organizations from the early decades have since disbanded, others like the National Women’s Health Network and Our Bodies Ourselves brought health feminism into a new century and influenced the work of younger women’s health activists and groups. The advent of the Internet has had a remarkable impact on the availability of health resources for the general public and on the outreach and education strategies of women’s health organizations. American feminist health activists now utilize new technologies and digital spaces, including social media platforms, to connect with the public and provide resources about women’s health care, patient self-advocacy, current health policy debates, and contemporary health crises and issues.

The Heroic Antedecents

In 1952 Terese “Ted” Lasser, the energetic and imperious matriarch of an affluent, well-connected family, unwittingly underwent a Halsted radical mastectomy at New York’s Memorial Hospital. She had been put to sleep for a “quick-section biopsy” with the assurance that her breast lump was almost certainly benign but awoke to find herself “wrapped in bandages from midriff to neck, bound like a mummy in surgical gauze.” She described her response to this event: “Somewhere deep inside you a switch is blown and your mind goes blank. You do not know what to think, you do not want to guess, you do not want to know.”

The Halsted radical mastectomy has with good reason been called “the greatest standardized surgical error of the twentieth century.” Introduced in the 1880s by William Halsted, founder of the surgery department at Johns Hopkins, it was debilitating, even crippling, and based on Halsted’s unproven belief that breast cancer was a local disease that could be fully, if brutally, excised before it spread. Soignée and energetic, Lasser, who was unaccustomed to being patronized, was furious at the doctor’s failure to state her options prior to her surgery. Later, neither her surgeon nor anyone else at Memorial Hospital would give her the specific information she demanded on treatment or exercises to regain the use of her arm, when or how to resume sexual relations, or even how to shop for a “falsie.”

Determined not to become disabled by the mastectomy, Lasser developed an innovative program of stretch exercises through which she regained her strength; better yet, she concluded, would have been to start exercising right after surgery. Naming her program R2R, Reach to Recovery, Lasser adopted a practice of slipping into the hospital rooms of new mastectomy patients, exhorting them to rise from their beds and crawl the fingers of their affected arms up the wall. Lasser personally counseled thousands of patients. Most of those who had the stamina to do the work showed results that seemed “miraculous” to their doctors, who were ultimately convinced. Lasser maintained a pretense that her calls were made at the requests of the patients’ surgeons or families. In truth, in the early years she was often “escorted out the front door of Memorial Hospital when she was found visiting patients at random and without the consent of the responsible surgeon.” In 1969 R2R merged with the American Cancer Society, becoming tame and traditional, activists say, so that they now find it hard to appreciate Lasser’s courage, or the ground that she first broke.

Thalidomide was a mild sedative, used in twenty countries, but at the FDA, Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey stubbornly refused to approve it for distribution in the United States, arousing the ire of her supervisors. In November 1961, when West Germany reported to the FDA that thalidomide had been associated with birth defects, Kelsey was not informed that her suspicions were correct. Thalidomide’s danger to pregnant women was not made public in the United States for a full year, until the Washington Post broke the story and President Kennedy presented Dr. Kelsey with a medal.

Enter Sherri Finkbine, the host of Romper Room, a franchised television show for pre-school children in Phoenix, the mother of four, once again pregnant, and a user of the thalidomide samples her doctor had provided. She confronted him and demanded a therapeutic termination of her pregnancy. At first the Phoenix hospital agreed to perform it, but then reneged. Finkbine called in the press, creating a “media avalanche” that opened a national debate on abortion law reform but ended her Romper Room career. As time ran out, she flew to Sweden for a legal procedure.

One must bear in mind that in the era of “heroic antecedents” a woman needed either “protection or connections” to successfully defend her health rights. Lasser had protection, in the form of a wealthy and powerful husband, J. K. Lasser, the author of the perennial best-selling income tax guides, while Finkbine, a TV personality, had fans and friends in the media. By the end of the decade many less affluent grassroots women, without “protections and or connections,” joined together to have an impact on health care. As Margaret Mead declared, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful and committed citizens can change the world. Indeed it is the only thing that ever has.”

The Militant Activists

From 1969 to 1975, the militant women’s health movement exploded with such velocity that nearly two thousand self-help women’s medical projects were scattered across the United States, according to a retrospective article in Science Magazine (Charles Mann, August 11, 1995). Mostly groups of volunteers without an institution, their strength derived from working together under the umbrella of the National Women’s Health Network (NWHN), which, after five years of informal networking, was formally incorporated as a not-for-profit organization on December 16, 1975. Sociologist Ruzek noted that in addition to informal self-help groups, by the mid-1970s more than 250 “formally identifiable groups” were working to advance the aims of the women’s health movement. Groups included feminist women’s health clinics, health education and health literacy groups, condition- and issue-specific organizations like the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse, and feminist health care referral services.

Our Bodies, Ourselves: Sharing Information

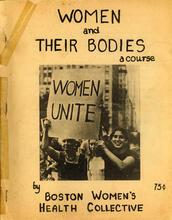

Social control, financial exploitation, and excessive medicalization of women through health care (especially obstetrics/gynecology and psychiatry) were the concern of the young feminists who, in May 1969, gathered for a workshop called “Women and Their Bodies,” led by social worker Nancy Miriam Hawley, the wife of an MIT professor, who lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Participants had hoped to come up with a list of good obstetrician-gynecologists they could trust but, recalls Jane Pincus, “We realized we didn’t know what questions to ask to find out if they were good or not.” Hawley and Pincus began a study group at which they distributed copies of their research. In 1970, they self-published their findings in a 193-page newsprint document, Women and Their Bodies. The following year, the authors retitled the booklet Our Bodies, Ourselves, in order to “emphasize women taking full ownership of their bodies” and it was republished by the New England Free Press.

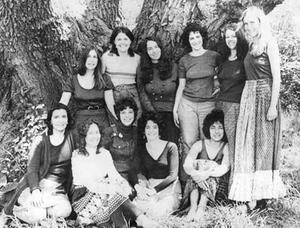

Demand grew and the women continued printing and expanding the “underground” booklet. They sold 250,000 copies of Our Bodies, Ourselves by 1973, when Simon and Schuster brought out the trade edition. At this point it became an international best seller, described as “the most powerful revolutionary document since Das Kapital because it induced women to seize the means of Reproduction.” Eight of the twelve women who formed The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective to write Our Bodies, Ourselves were Jewish—Nancy Miriam Hawley, Jane Pincus, Vilunya Diskin, Pam Berger, Joan Ditzion, Paula Doress-Worters, Ruth Bell Alexander, and Esther Rome. The remaining four were Judy Norsigian, Wendy Sanford, Norma Swenson, and Mary Stern. Since 1970 more than three and a half million copies have been printed in twelve different languages. Royalties go to women’s health projects and to the Women’s Health Information Center maintained by the Collective. In 2002, the organization began to operate under the name of its primary publication and call themselves Our Bodies Ourselves (OBOS).

The National Women’s Health Network: Establishing Our Rights

Also in 1969, journalist Barbara Seaman published The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill. Influenced by Seaman’s book, U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson called on her to help his staff prepare Senate hearings on whether women were given accurate information about the pill. Radical feminists disrupted the male-dominated hearing and demanded that women taking the pill be informed of all the potential dangers and side effects.

While Alice Jacoby Wolfson and other members of Washington D.C. Women’s Liberation were meeting to analyze “body issues,” focusing on contraception and the side effects of the birth control pill, they read about Seaman’s book and the Senate hearing in articles in the Washington Post by Victor Cohn. They decided to attend the hearings.

The issue was not the safety of the pill, for British studies had established deaths from strokes, heart attacks, and blood-clotting. The issue was whether women understood these risks. In January 1970, Wolfson was a seasoned veteran of the civil rights and anti-war movements who had participated in many demonstrations. In the Senate Hearing Room, her feminist soul connected with her long experience in civil disobedience. As she would write in her memoir three decades later: “We went to the Hill to get information. We left having started a social movement.”

Alice Wolfson was disturbed by the testimonies of the scientists: the pill was too strong; it was placed on the market without dose adjustments; it caused not only cardiovascular disorders but also high blood pressure, depression, infertility, rare birth defects, liver disease, reproductive cancers, and even hair loss. She jumped up from her seat in the audience and shouted, “Why are no patients testifying? All of the women here have suffered ill effects of the Pill. And we were told by doctors while suffering these effects, and afterwards, to go on taking the Pill.”

Her colleagues added to the fracas, enumerating their complaints and the heartlessness of some doctors. At times, the Senate guards were heartless too: a frequently reproduced Associated Press photograph shows the very pregnant Marilyn Salzman Webb (founder of the women’s liberation newspaper Off Our Backs) in a hand-to-hand struggle with a guard who is removing her from the hearing room. That evening the Wolfson women were featured on the network news. Dr. Elizabeth Siegel Watkins, historian of science, described the impact of that first day of civil disobedience in her book On the Pill:

Anyone who had not previously been aware of this growing controversy was immediately clued in by watching the evening news on January 14, 1970. The first minutes of televised news about the pill hearings portrayed several of the conflicts surrounding the oral contraceptives.

First, the debate within the medical profession over the safety of the pill was highlighted with emphasis on the critics of oral contraception. Second, the confrontation between D.C. Women’s Liberation and the all-male Senate subcommittee was presented, demonstrating the tensions between the budding feminist movement and the existing establishment in government, industry, and medicine. Third, the statement of the members of the women’s liberation movement revealed the lack of communication between doctors and their female patients.

Over nine days of hearings, concluding on March 4, the Wolfson women devised strategies to scatter themselves around the hearing room, bringing in new recruits and new faces. On January 25, when all three networks featured the women’s protest on the evening news, television viewers worldwide were stunned to hear such accusations as “Why have you assured the drug companies that they could testify? They’re not taking the pills, we are!” “Women are not going to stay quiet any longer. You are murdering us for your profit and convenience.” As Science Magazine noted in 1995, “Even as the hearing bared the pill’s safety defects, the dissent helped to launch a political movement focusing on women’s health.” In 2003 Chana Gazit, a native of Israel, wrote and directed The Pill, an award-winning television documentary, for PBS’s American Experience series. Her film includes dramatic newsreels of the dissent in the Senate, as does an earlier documentary (also much honored) produced by Erna Buffie for the Canadian Film Board.

In June 1970, the health feminists achieved a victory when the FDA mandated that all oral contraceptive packages must contain a patient warning. Historian Nancy Tomes argued that while this was not the first time the FDA required a patient insert for a prescription drug (the agency required a written warning for an asthma inhaler two years prior), the patient insert for birth control “received significantly more attention.” Tomes described how activists celebrated the patient insert for birth control as a “significant victory for the women’s health movement and for medical consumerism in general.”

The National Women’s Health Network grew out of the activist association of Wolfson and Seaman, along with others who joined with them in the following months and years. The three other co-founders were Belita Cowan, publisher of Herself Newspaper in Ann Arbor, who exposed seriously flawed research on DES as a morning-after contraceptive that was conducted at the University of Michigan Health Service and published in The Journal of the American Medical Association; Mary Howell, first woman dean at Harvard Medical School, who helped to force medical schools to abandon their secret quotas against women though her underground broadside Why Would a Girl Go into Medicine?; and psychologist Phyllis Chesler, who held mental health practitioners to a less sexist standard through her classic work Women and Madness. Of the five co-founders, all but Dr. Howell were Jewish. Belita Cowan, whose example of healthy skepticism sparked feminists all over the world to interview patients and discover abuses in the trials of other contraceptives, including Norplant, became the NWHN’s first executive director.

Incorporation was celebrated with a demonstration. This time it was a memorial service on the steps of the FDA building for all the women who had died from the careless use of hormone products, including the pill, menopause estrogens, and DES. Dr. Richard Crout, head of the FDA’s Department of Drugs, who happened to pass by, was so moved by the stories of mourners that he stepped forward and promised to provide patient-warnings on all hormones.

Among the many feminist organizations that flourished in the 1970s, those in the practice of health advocacy were the most multicultural, able to draw substantial numbers of minority women. By the late 1970s, NWHN supporters and contributors consisted of individuals, such as feminist sociologist and Chicago-based women’s health researcher Pauline B. Bart and D.C-area breast cancer activist Rose Kushner, as well as organizational supporters across the nation like the American College of Nurse-Midwives, the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, the UAW Solidarity House in Detroit, and organization Indian Women United for Justice. The NWHN reported at the time that their membership’s three top priorities were issues of informed consent/patients’ rights, reproductive health, and national health insurance. For nearly fifty years, NWHN has held to the promise expressed in its charter—never to take any drug industry money.

Self-Help Gynecology: Taking Intimate Matters into our Own Hands

Over the course of only two years, two Los Angeles area housewives, one Jewish (Lorraine Rothman) and one gentile (Carol Downer), had an immeasurable impact on major women’s rights legislation such as Title IX in 1972 and court decisions such as Roe v. Wade in 1973.

Like many others, Carol Downer was inspired by Alice Wolfson. On January 14, 1970, Downer was driving her car on a Los Angeles freeway when she heard on the radio that “women’s libbers are rioting in the U.S. Senate.” She pulled over and stopped her car, which, she recalls, she had almost crashed in her excitement and delight. The working-class mother of a large family, Downer was part of the abortion reform movement. She was disappointed in California’s 1967 Therapeutic Abortion Act that made abortion available only in accredited hospitals, only up to twenty weeks, and subject to approval by a panel of doctors.

Women’s access was severely limited by class, race, and age. Adult white women with money could obtain abortion, while young women, poor women, and women of color had far less access. Downer pondered how California women might take this into their own hands. Fifteen months later, on April 7, 1971, she organized the first “self-help” clinic, which took place at a feminist bookstore where she jumped on a table, inserted a speculum into her vagina, and invited the other women to observe her cervix.

They discussed and examined abortion tools, some of them deciding to learn to perform abortions themselves. Then, as Downer explained, “One attendee, Lorraine Rothman, returned to the next meeting with the prototype of a device called the Del-Em that made it possible for women with minimal training to perform either menstrual extraction or early abortion. The Del-Em is a simple suction device consisting of a sterile plastic tube, the circumference of a pencil, which is inserted in the uterus to extract the contents into a small glass mason jar. A valve prevents air from being injected into the uterus. After observation, training and improvements in the Del-Em, the small group successfully performed early abortions and menstrual extractions in private homes.” They traveled around the country to hold self-help meetings, and clinic groups sprang up in their wake.

In 1973, when Roe v. Wade made abortion legal, some of these groups formed the nuclei of women-controlled abortion centers and the collective organized as the Federation of Feminist Women’s Health Centers. Several eminent doctors—and Margaret Mead—became admirers of Lorraine Rothman and her Del-Em. Mead declared that in each century there are only one or two “truly original ideas,” and, for the twentieth, menstrual extraction was it, because no one before had found a gentle way to remove the menstrual flow all at once.

Lorraine Rothman was born in San Francisco in 1932 to parents who emigrated from the Ukraine. They were a large extended family with fifteen first cousins, all very close. Religiously, they were Conservative. Rothman’s mother and grandmother were both healers, women called on by the community for home remedies, sometimes reciprocated with chickens and eggs. Her father was a furniture maker. “Both parents,” Rothman recalled, “knew how to make a little stretch a long way. They wasted nothing, they knew how to repair almost anything.” Lorraine, who inherited their skill, developed the Del-Em and patented it shortly afterwards, holding the design in trust for all women who follow the self-help clinic concept.

Rothman was co-founder of two Feminist Women’s Health Centers, in Los Angeles and Orange County. She and Downer shared a down-to-earth sense of humor. As a result of their successful demonstrations throughout the United States these “tigers at the gates” helped to influence the Supreme Court’s decision to approve abortion.

Why Me?: Demanding the Right Research

Rose Kushner, diagnosed with breast cancer in 1974, wrote an influential book called Breast Cancer: A Personal History and an Investigative Report and opened her Breast Cancer Advisory Center in 1975, while also chairing the National Women’s Health Network Breast Cancer Task Force. Kushner, who was given DES during her three pregnancies, became convinced that this was a likely cause of her illness. (DES was an estrogen given to pregnant women from the 1940s to 1960s in the belief that it would prevent miscarriages.) She grew angrier yet at her doctors when they persuaded her to get implants after her mastectomy (so that she could feel like a “real” woman) and the implants burst.

A journalist before she became a health activist, Kushner’s writing was central to her breast cancer work. Kushner revised Breast Cancer and published the updated edition with the new title Why Me?: What Every Woman Should Know About Breast Cancer to Save Her Life in 1977. In her work, Kushner challenged the use and efficacy of the Halsted radical mastectomy and called for women to be informed about alternative treatments and for patients to pursue second opinions. She also pushed for the elimination of one-step mastectomy procedures, also described as a “one-stage, biopsy-mastectomy procedure.”

Kushner’s parents, the owners of a small shop in Baltimore, died during the Depression when she was very young. She was cared for by aunts who had little money, and the highlight of her weekends was a social worker who visited with food and clothing. In her oral history, taken by fellow feminist health activist and journalist Anne S. Kasper for the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College, Kushner recalled that she vowed to be “a social worker for women who have breast cancer.” She was brash, brilliant, and so driven that, in an unprecedented move, President Jimmy Carter appointed her, a “mere patient,” to the national Cancer Advisory Board, where she defended informed consent, exposed the fallacies in poor-quality research (a skill she learned from Belita Cowan in their work together at the National Women’s Health Network), and stirred up much controversy. She influenced the fall from grace of the “quick-section biopsy” that Terese Lasser deplored by getting the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to collect and examine old results, which proved alarming. It was discovered that in their haste, pathologists had often made false positive diagnoses. In other words, because a too hasty diagnosis was made while she was on the operating table, at least one woman in fifteen or twenty who thought she had breast cancer actually did not. Kushner’s constant muckraking raised sentiment—and government financing—for the trials that compared lumpectomy and mastectomy, concluding that the lesser surgery was equally effective.

In the 1990s breast cancer activism accelerated and could be found everywhere. Millions of women participated in the United States. If asked why they became militant, most of them would say it was due to the example of AIDS activism among gay men, and specifically colorful groups such as ACT UP. Yet, at meetings or on radio shows at which AIDS and breast cancer advocates conversed, if a breast cancer spokeswoman thanked a representative from the AIDS community, he would often modestly correct her with “Didn’t you know Rose Kushner?” or “We took a lot of tips from the women’s health movement.” AIDS activists studied the tactics of feminist health activists, especially as they planned their own demonstrations at the FDA.

How this happened has been explained by Risa Denenberg: “I wrote a chapter for the Lesbian Health Book (White and Martinez) on the history of the Lesbian Health Movement, in which I reviewed how the different health movements built on each other’s work. I vividly recall going to the FDA sometime in the 1970s to protest experimentation with DES, and the deep irony I felt returning to the FDA in the 1990s with ACT UP to demand speedier drug delivery. The women’s caucus of ACT UP put together a huge handbook about the women’s health movement and presented it as a teach-in to a few hundred ACT UP men and I think most of the guys really took the lessons to heart.”

Denenberg was born in Washington, D.C., in 1950 and raised in an observant, Conservative Jewish family. She was a nurse practitioner with a Masters of Nursing degree from Columbia University and before moving to New York spent fifteen years with the Feminist Women’s Health Center in Tallahassee, Florida. “Being Jewish and the hope for tikkun olam [repairing the world] is really a foundation for caring about everything that I care about.”

Professional Advocates

Ruth Merkatz’s parents left Germany in 1934 because her father, a young physician in training, was not permitted to practice medicine. A dedicated practitioner in Rockland County, New York, he allowed his daughter to help him in his office and on weekends to go on calls with him. Demanding, and with high expectations of his children, he instilled in her a passion to help others and “even though she was a girl” to have a career that made a difference. In the early years of her career, she was a leader in the small corps of nurses who pressed for and won more humane obstetrics practices, such as families being present at childbirth, and the return to breastfeeding. As an academically distinguished PhD nurse, she advocated for patients. In 1991 she created and served as the first director at the FDA’s Office of Women’s Health. She changed the agency’s policy on women in clinical trials and introduced the analysis of drug data for gender effects. Discovering that some mammography services were inadequate or even dangerous, she established oversight, as well as a Mammography Information Service for patients. One of the first public health officials to predict the extent of the spread of AIDS to women, she worked on the National Task Force on AIDS Drug Development. In 1997 Merkatz joined Pfizer, leading a new division focused on a comprehensive approach to women’s health.

Dr. Florence Haseltine did not know she was Jewish until she was eighteen years old. As a child she was hyperactive and dyslexic and attended special education classes, where she helped look after the classmates who were severely handicapped. She overcame her problems and had a brilliant twenty-year career as director of the Center for Population Research at the National Institutes of Health. In 1976 she published a book called Woman Doctor, which was used as a reference in women’s studies courses, illustrating the training experiences and sexual harassment that prevailed before the phenomenon was even recognized. In 1990 she founded the Society for Women’s Health Research, which advocates for, and funds, research in women’s health. Her concern at the time was the lack of research in the areas of contraception and infertility, which had become extremely limited due to political debates over abortion. She was a key figure in influencing feminist-minded women in Congress to open up the issue of sexism in research for public scrutiny. Through her Society for Women’s Health Research, she stirred up an enormous amount of press coverage in favor of the Women’s Health Equity Act, which became law in 1993.

Dr. Judith Lewis Herman, a Harvard psychiatrist with early ties to the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, wrote a book that changed the way battered women are viewed by doctors and psychiatrists. In 1992, she published Trauma and Recovery, which clarified that domestic violence victims (no longer denounced as masochists) suffer from the same Post Traumatic Stress Disorder as war veterans and prisoners of war.

Heated controversies on women’s right to “clean” abortions are not likely to go away. Rebecca Gomperts, a Dutch gynecologist, is also certified in ship navigation. Her foundation, Women on Waves, converted a ship into a reproductive health clinic, which offers offshore abortions and other services in international waters to women who cannot obtain them legally in their home country. Gomperts is motivated by her anguish over unnecessary abortion deaths and her sense of justice. She points out that twenty-five percent of the world’s population lives in places with highly restrictive abortion laws. “Twenty million of the fifty-three million abortions every year are performed under unsafe and illegal conditions, resulting in the death of approximately one hundred thousand women annually. This is a medical calamity.”

New Digital Spaces, Familiar Debates: Women’s Health Activism in a New Century

Women’s health activists of the twenty-first century continue to address many of the concerns seen in earlier decades. Reproductive justice, national health insurance, racial inequities in health care access and treatment, and drug and medical product safety remain key issues. In addition to addressing longtime challenges, women’s health activists in recent years have engaged with issues such as the HPV vaccine Gardasil, controversial new drugs like Addyi (a treatment for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in pre-menopausal women), the need for greater health resources for the transgender community, and addressing the alarming rates of maternal mortality in the United States, especially among women of color. Journalist Jennifer Block wrote in 2019 of “feminism’s unfinished revolution in women’s health” in her book Everything Below the Waist. The revolution undoubtedly remains unfinished, yet activists continue the vital work of the women’s health movement as it negotiates twenty-first century health politics and care.

Women’s health activists increasingly utilize websites, blogs, and social media to advocate for women’s health reform and provide updated information about health policy, drug safety, and more. Longtime organizations like the National Women’s Health Network, the Black Women’s Health Imperative, and Our Bodies Ourselves maintain websites where visitors can find trustworthy information about women’s health, learn how to support or join specific initiatives, and follow developments in health policy issues such as the Affordable Care and Patient Protection Act, Medicare and Medicaid, and maternal and infant health.

In 2016, more than 500,000 people per month visited the Our Bodies Ourselves website for health information and resources. Despite its popularity, Our Bodies Ourselves announced two years later that it would no longer publish updated editions of its health manual due to financial struggles and that the group would transition to a volunteer-led organization. Still, the 2011 edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves remains in print and guest blog authors continue to provide information about current issues. Our Bodies Ourselves is also working with the Center for Women’s Health & Human Rights at Suffolk University to create “Our Bodies Our Selves Today,” an inclusive online resource on health, sexuality, and well-being for “all kinds of women and girls, trans men, and nonbinary folks.” Jewish women continue to be active in Our Bodies Ourselves in many capacities, including serving on the board of directors and the organization’s advisory board.

The NWHN also continues to be an active organization. Recent campaigns include the fight to expand Medicaid coverage in all 50 states, protect access to the abortion pill, push back against COVID-19 misinformation, and provide women with updated information about vaccine safety. In the Fall of 2020, the NWHN also hosted its first virtual event emphasizing the intersection of COVID-19, the Black Lives Matter movement, and women’s health rights. The NWHN also developed a free “Health Empowerment Academy,” which provided participants lessons via email on topics like patient self-advocacy, evaluating health information, and understanding health care stakeholders. In addition to in-person organizing, regional and local women’s health groups also utilize digital spaces and social media platforms to reach the public and other activists, coordinate demonstrations and events, and answer inquiries from the community.

Social media has been particularly important in raising awareness of women’s issues through hashtag campaigns, including the #MeToo movement, which mobilized online and in person against sexual abuse and sexual harassment. Social media platforms are utilized by women and patients generally to connect with others who share their struggles, or by health professionals looking to reach patients and the community in informal spaces.

Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook also are utilized as an outreach and education tool by groups like the Queer Doula Network, the National Black Doulas Association, and “The Radical Doula” community, a group who connected through the website and blog founded by Miriam Zoila Pérez. Though social media helps patients access a range of health information and communities, it can also expose users to online harassment and it is difficult to quantify the exact impact of “hashtag activism.” Nonetheless, public health practitioners and scholars Aida E. Manduley, Andrea Mertens, Iradele Plante, and Anjum Sultana have found that social media provides an accessible and responsive space for expanding health education and literacy, and especially sexual health literacy, for “queer, trans, and racialized communities…who have been historically maligned by state-based sex education.”

In the early twenty-first century, Jewish women have been active in creating women’s health communities online and in person. As women’s health advocates in a wide variety of groups, they have both fought for broader, more universal issues such as national health insurance and organized to serve the Jewish community specifically around issues such as breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and infertility.

Some Jewish women who were active in the 1970s and 1980s-era women’s health movement continued to be active well into the 2000s. In her work as a community organizer and women’s health advocate, sociologist Anne S. Kasper underscored the importance of a “social model of women’s health” and an intersectional approach to social justice in women’s health. “None of us live in a vacuum, separate from the impact that a multitude of social, economic, political, and other factors has on our lives,” wrote Kasper in 2002. “Learning to see with a social lens, to think critically about how the contours of a patient’s life circumstances shape the problems she brings to the doctor’s office, may go a long way in helping the clinician to be more attentive and more caring and to better provide for the needs of the patient.”

Jewish women have also created organizations and online communities to help support other Jewish women and families navigating specific health concerns. In 2002, Rochelle L. Shoretz founded Sharsheret, a national non-profit organization that provides support to Jewish women and families facing breast and ovarian cancers. Sharsheret provides a wide range of resources, including information about hereditary cancer, the BRCA+ gene mutation, and support for caregivers.

Jewish women have also utilized Instagram and Facebook to connect with one another over shared women’s health concerns and experiences. In 2019, pediatrician Aimee Baron founded the social media community I Was Supposed to Have a Baby on Facebook and Instagram to support Jewish individuals and families struggling with infertility. Baron described the online forums as “an immediate success” and Jewish men and women alike joined the community. “Stories poured in from around the world, with women clamoring to share their experiences, tips, and support. Finally, Jewish people struggling with infertility had a place,” wrote Baron.

Since the late 1960s, Jewish women have helped create and sustain the women’s health movement through decades of substantial social, political, medical, and technological change. Historians are now increasingly exploring how Jewish health activists interwove their Jewish identities, their feminism(s), and their activism during the height of second wave feminism. Expanding on her earlier work on Jewish women in the second wave, Joyce Antler’s Jewish Radical Feminism (2018) contains an entire chapter on the role of Jewishness and Jewish identity in the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. Jillian M. Hinderliter’s article on Seaman and Kushner in the journal American Jewish History argues that histories of the women’s health movement must consider Jewish women activists as feminists and as American Jews to fully represent their experiences and influences. Jewish activists of the women’s health movement have also helped build the historical record by sharing their own stories through oral history interviews, memoirs and other reflective essays, and donating their personal papers to archives. Organizations like Jewish Women’s Archive are essential in sharing Jewish health feminists’ stories and reflections on accessible online platforms.

Jewish women helped build and sustain the feminist women’s health movement in the United States in the twentieth century. In the twenty-first century, Jewish activists continue to redefine the methods and messaging of feminist health activism as the movement navigates new women’s health concerns and political challenges. Whether working on behalf of women’s health issues broadly or providing resources to the Jewish community specifically, Jewish women continue to shape women’s health care, policy, and the patient experience in America.

Wherever there are “medical calamities”; wherever there are unjust or sexist laws placing women in harm’s way; wherever there is excessive medicalization of childbirth or menopause; whenever drug or medical industry profits are valued above people; or the true balance between benefits and risks in questionable products for women are concealed—that is where we will always find courageous Jewish women working to heal the world.

Selected Readings and Resources

Organizations

National Women’s Health Network

Boston Women’s Health Book Collective

Feminist Women’s Health Centers (aka Ceder River Clinics)

Women’s Health Specialists of California (Originally Chico Feminist Women’s Health Center)

Black Women’s Health Imperative

Reach to Recovery Program (American Cancer Society)

Memoirs/Biographies

Baker, Christina Looper and Christina Baker Kline, eds. The Conversation Begins: Mothers and Daughters Talk about Feminism. New York: Bantam Books, 1996.

Chesler, Phyllis. A Politically Incorrect Feminist: Creating a Movement with Bitches, Lunatics, Dykes, Prodigies, Warriors, and Wonder Women. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2018.

Chesler, Phyllis. Letters to a Young Feminist. Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 1997.

Kushner, Rose. Breast Cancer: A Personal History and An Investigative Report. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1975.

Rollin, Betty. First, You Cry. New York: Lippincott, 1976.

Katz Rothman, Barbara. “In Which A Sensible Woman Persuades Her Doctor, Her Family, and Her Friends to Help Her Give Birth at Home.” Ms. Magazine (December 1976): 25–32.

Adler, Margot. A Heretic’s Heart: A Journey Through Spirit and Revolution. Boston: Beacon Press, 1997.

Wolfson, Alice. “Clenched Fist, Open Heart.” In The Feminist Memoir Project: Voices From Women’s Liberation, edited by Rachel Blau Du Pleiss and Ann Snitow, 268–283. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1998.

Films

Taking Our Bodies Back: The Women’s Health Movement. Margaret Lazarus, Cambridge Documentary Films: 1974.

A Private Matter. A film on Sherri Finkbine directed by Joan Micklin Silver with Sissy Spacek as Sherri. Home Box Office: 1992.

The Pill. Erna Buffie/Elise Swerhone, National Film Board, Canada: 2000.

The American Experience Presents: The Pill. A Steward/Gazit Production for the American Experience. First aired on February 24, 2003.

Overview Histories

Antler, Joyce. Jewish Radical Feminism: Voices from the Women’s Liberation Movement. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Antler, Joyce. The Journey Home: How Jewish Women Shaped Modern America. New York: Schocken Books, 1997.

Chalker, Rebecca, and Carol Downer. A Woman’s Book of Choices. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1992.

Goldman, Marlene B., and Maureen C. Hatch, eds. Women and Health. San Diego: Academic Press, 2000.

Kline, Wendy. Bodies of Knowledge: Sexuality, Reproduction, and Women’s Health in the Second Wave. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Mann, Charles. “Women’s Health Research.” Science Magazine (cover story, August 11, 1995): 766–801.

Morgen, Sandra. Into Our Own Hands: The Women’s Health Movement in the United States, 1969-1990. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2002.

Nelson, Jennifer. More Than Medicine: A History of the Feminist Women’s Health Movement. New York: New York University Press, 2015.

Nelson, Jennifer. Women of Color and the Reproductive Rights Movement. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

Ruzek, S. B. The Women’s Health Movement: Feminist Alternative to Medical Control. New York: Praeger, 1978.

Seaman, Barbara, and Susan F. Wood. “Role of Advocacy Groups in Research on Women’s Health.” In Women and Health, edited by Marlene B. Goldman and Maureen C. Hatch, 27–36. San Diego: Academic Press, 2000.

Tomes, Nancy. Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

Vyas, Amita N., Liz Borkowski, Chloe E. Bird, et al. “Editor’s Note: 30 Years of Women's Health Issues.” Women’s Health Issues 31, no. 1 (2021): 1-3.

Watkins, Elizabeth Siegel. On The Pill: A Social History of Oral Contraceptives, 1950–1970. Chapters 5 and 6. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Webb, Marilyn. The Good Death: The New American Search to Reshape the End of Life. New York: Bantam, 1997.

Weisman, C. S. Women’s Health Care: Activist Traditions and Institutional Change. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Women’s Research Center et al. How to Stay Out of the Gynecologist’s Office. California: Pease Press Publishing, 1981.

Selected Writings and Studies

Bart, Pauline. “Depression in Middle-Aged Women” (a/k/a “Portnoy’s Mother’s Complaint”). In Women in a Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness, edited by V. Gornick and B. Moran, 99–117. New York: Basic Books, 1971.

The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. Women and Their Bodies. Somerville, MA: 1970 (name changed to Our Bodies, Ourselves in 1971); Our Bodies, Ourselves. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971 (first trade edition); re-titled The New Our Bodies, Ourselves (1984), updated and expanded for the 1990s (1992), twenty-fifth anniversary edition (1996), Our Bodies, Ourselves for the New Century. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998.

Block, Jennifer. Everything Below the Waist: Why Health Care Needs a Feminist Revolution. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2019.

Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1975.

Chesler, Phyllis. Women and Madness. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1972.

Firestone, Shulamith. The Dialectic of Sex. New York: William Morrow & Co., 1970.

Ford, Liz. “Women’s Rights Activists Use Social Media to Get Their Message Out.” The Guardian. March 18, 2015.

Frankfort, Ellen. Vaginal Politics. New York: Quadrangle Books, 1972.

Herman, Judith. Trauma and Recovery. New York: Basic Books, 1992.

Hinderliter, Jillian M. "Muckraking Wonders: Jewish Journalist-Activists of the US Women's Health Movement, 1969–1990." American Jewish History 104, no. 2 (2020): 371-395.

Hubbard, Ruth. The Politics of Women’s Biology. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Kasper, Anne S. “Understanding Women’s Health: An Overview.” Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 45, no. 4 (2002): 1189-1197.

Lasser, Terese and William Kendall Clarke. Reach to Recovery. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1972.

Locke, Abigail, Rebecca Lawthom, and Antonia Lyons, “Social Media Platforms as Complex and Contradictory Spaces for Feminisms: Visibility, Opportunity, Power, Resistance, and Activism.” Feminism & Psychology 28, no. 1 (2018): 3-10.

Manduley, Aida E., Andrea Mertens, Iradele Plante, and Anjum Sultanta. “The Role of Social Media in Sex Education: Dispatches from Queer, Trans, and Racialized Communities.” Feminism & Psychology 28, no. 1 (2018): 152-170.

Reitz, Rosetta. Menopause: A Positive Approach. New York: Penguin, 1977.

Rich, Adrienne. Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution. New York: W.W. Norton, 1976 (paperback: 1986).

Rothman, Lorraine. Menopause Myths and Facts: What Every Woman Should Know About Hormone Replacement Therapy. Los Angeles: Feminist Health Press, 1999.

Seaman, Barbara. The Doctors’ Case Against the Pill. New York: P.H. Wyden, 1969 (revised and updated: New York, 1980; twenty-fifth anniversary edition, updated, new material, with original text restored: Alameda: 1995).

Seaman, Barbara. Free and Female. New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1972.

Seaman, Barbara, and Gideon Seaman, M.D. Women and the Crisis in Sex Hormones. New York: Rawson, 1977.

Seaman, Barbara, and Gary Null. For Women Only! New York: Seven Stories Press, 2000.

Seaman, Barbara. The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003.

Seaman, Barbara, and Laura Eldridge. Voices of the Women’s Health Movement, Volumes I and II. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2012.

Tanzer, Deborah, with Jean Libman Block. Why Natural Childbirth? New York: Schocken Books, 1972.

Turley, Emma and Jenny Fisher. “Tweeting Back While Shouting Back: Social Media and Feminist Activism,” Feminism & Psychology 28, no. 1 (2018): 128-132.

Weisstein, Naomi. Psychology Constructs the Female, or the Fantasy Life of a Male Psychologist. Somerville, MA: New England Free Press, 1971.

Wolfson, Alice. “Health Care May Be Hazardous to Your Health.” Up From Under, Vol. 1, Issue 1 (1970): 5–10.

Periodicals

Her-Self. Ann Arbor, Michigan: 1972–1975, Belita Cowan, ed.

Ms. Magazine. Nina Finklestein (Board member of National Women’s Health Network), health editor. 1972–1980.

New Directions for Women. Dover, New Jersey, 1972-1993, Anne S. Kasper (member of National Women’s Health Network and breast cancer advocate) served as health editor from 1979-1984.

Related Archival Collections

Pauline B. Bart Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.

Phyllis Chesler Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Duke University.

Rose Kushner Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

National Women's Health Network Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts.

Barbara Seaman Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

With special thanks to Susanne Wood, Judith Rosenbaum, Laura Eldrige and Agata Rumprecht, and Bethany L. Johnson.